“If labor organizers had learned anything from decades of small victories and stubborn failures in the US South, it was that interracial unions were hard work.”

“I have your letter of June 1 [1974] and suggest that if you really want to know what is involved in organizing a Union, you should put some time into working to build one.” Mack Lyons seemed impatient, even dismissive. He had other things on his mind. As director of the United Farm Workers (UFW) Union in Florida, he had worked tirelessly for the last two-and-a-half years. Driving an aging 1968 Ford station wagon across the state, from swampy South Florida to the capital of Tallahassee, he gave countless speeches in churches, at local unions, and at political rallies; and, with his wife Diana Lyons and a small team of volunteers, planned, negotiated, and administered the first farmworkers’ collective bargaining agreement in Florida’s history. It was a contract between the Black, Mexican American, and white workers in Florida’s citrus groves and one of the most powerful companies in the world, Coca-Cola, which owned the Minute Maid groves and company houses where those workers lived and toiled.1

Mack was responding to a letter that sat in the usual heap of correspondence that arrived daily at the Florida headquarters of the United Farm Workers. It was a well-meaning inquiry from a student at the historically Black Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. The student wanted to know how, under Mack Lyons’s leadership, the California-based UFW had been able to win such an improbable contract. What were the main problems of organizing farmworkers? What could be done to replicate their unprecedented success across the state of Florida?

It was a chance for Mack to reflect on his time as an organizer and explain how an understaffed crew of volunteers from California and local grove workers had forged an interracial union within a multiracial political coalition in the 1970s U.S. South. The state was deeply hostile to labor unions, whose workers the Florida legislature described as “the most economically and socially deprived” in the nation. Even if Mack had the energy, neatly formulating abstract principles was not really his forte: “I cannot take the time from a very busy schedule to write for you a dissertation on what is required in building a union for farmworkers.” He was pragmatic, flexible, suspicious of theorizing. As Mack realized, it was hard to put into words. Conscious, day-to-day effort in the union and in the community created solidarity in practice, through methods that Mack and Diana Lyons deliberately and painstakingly cultivated in the UFW’s tumultuous first years in Florida’s citrus groves.2

“I had never saw any grapes”

Mack Lyons had come a long way to get to Florida. He was born in 1941 near Dallas, to parents who worked in Texas cotton fields. He moved around the Southwest, including a stint hustling pool in Las Vegas, until in 1966 he settled with his first wife in Central California’s San Joaquin Valley. In Texas, he had been a farmworker inconsistently, and deliberately so. It was grueling work that he avoided as much as possible. Now in California and needing money, Mack and a few friends took a truck and went looking for a job in Delano’s sprawling grape fields. Mack said that until he pulled up to the edge of that DiGiorgio grape field in Delano, he “had never saw any grapes.” But it was not the fruit that made a lasting impression on him. It was the picket line of people, primarily Mexicans and Mexican Americans, holding flags emblazoned with a striking black Aztec eagle against a bright red background, and signs that read, in all capital letters, HUELGA.3

Mack recalled that neither he nor any of the other Black farmworkers he was riding with knew any Spanish. Huelga is Spanish for “strike,” and what Mack saw were the early days of Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers striking in the Delano vineyards. Before the decade was over, everyone in California would know what huelga meant.4

Apprehensive but curious, Mack talked to the UFW members on the picket line. They likely explained to him that the strike began a year earlier, in 1965, initiated by the largely Filipino Agricultural Workers of California (AWOC) and followed by the largely Mexican American National Farm Workers of America (NFWA), led by Cesar Chavez, against the grape growers in the San Joaquin Valley. They likely explained that these growers cheated field workers out of wages, used state-subsidized labor in the Bracero Program as competition, exposed workers to harmful pesticides, and treated them as barely human. The growers attempted to break the unions’ strike by pulling in workers from elsewhere and having picket line demonstrators arrested. When Mack showed up looking for work that day, he himself had been an unwitting strikebreaker.5

The farmworkers had to figure out how to outmaneuver the growers, who had seemingly endless resources and local, state, and national political influence. In 1966, union leadership hatched two ideas: nationwide boycotts of grapes, which became the largest consumer boycott in American history; and a peregrinación, a pilgrimage, made from Delano to Sacramento with marchers holding large wooden crosses and posters of the Virgin of Guadalupe. UFW members drew parallels between their approach and the contemporary Black freedom struggle, and it was from the Civil Rights Movement that the UFW drew its image as “a ‘movement’ more than a ‘union.’ Once a movement begins it is impossible to stop,” as an editorial in El Macriado put it. The pilgrimage galvanized ecumenical religious sympathy, not only among Mexican American and Filipino American Catholic farmworker communities but also among a broad base of liberal Protestant churches. In 1966, against the protestations of some members, AWOC joined with NFWA to become the United Farm Workers of America, led by Cesar Chavez and funded by the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (ALFCIO). It was a pragmatic move. Most California farmworkers were Mexican American, and the promise of AFL-CIO funding was hard to ignore.6

Mack was in. Quick to joke or jump into song, with “long legs” and a “languid smile,” Mack was a constant presence within the union. Over the next three years, he worked nonstop around the valley, organized pickets, picked grapes in fields where contracts were won, and was elected steward, a union representative among workers in Arvin, near Delano, by a field crew composed of Mexicans, Filipinos, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and white southerners. Mack “must be a nice guy,” Chavez remarked, and admired that Mack was able to get such a diverse group of workers to agree on anything. Chavez came to respect Mack as much as his fellow workers did. Only years after joining the union did Mack come to be the sole Black member of the UFW executive board and of Chavez’s inner circle.7

The United Farm Workers was never just a labor union. Before he organized farmworkers, Chavez got his start as a community organizer on the payroll of Saul Alinsky, the Chicago-based community organizer and political theorist. During his tenure as UFW president, Chavez was sometimes accused by fellow members of being more interested in leading a national social movement like Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr.—two of Chavez’s foremost inspirations—rather than dealing with the everyday toil of a labor union. In practice, the UFW was at least three distinct things. After winning contracts with grape growers pressured by the boycott, it was officially a labor union. It was also a community organization offering medical and legal services, social events, and political representation to members and nonmembers. And as produce boycotts drew national sympathy, Chavez insisted on a more expansive vision, aiming to provide economic justice for all poor Americans, reimagining the UFW as a nationwide social movement.8

When the UFW was working properly, these three elements were seamless. When it was not, internal and external critics tore into Chavez for being unable to decide on the goals and identity of the union. After the successes of the 1960s, the struggles of the ’70s were more complicated and bitter. Protracted fights with strikebreaking members of the Teamsters Union (a more politically conservative union brought in by growers to replace the UFW), interminable boycotts, and the passage and subsequent lack of support for statewide agricultural labor legislation left the union diffuse and exhausted, a symbol without much reality. In California, the UFW became a social movement without a labor union. In Florida, it was the other way around. It would become a sustained labor union without an accompanying social movement. But in its first decade everyone in UFW’s California offices were optimistic, riding high off of contracts won throughout the state. Mack, committed to realizing the UFW as a labor union and eager to be on the ground organizing and interacting directly with workers, said to Chavez, partly in jest, “Let’s consider California liberated and move somewhere else!”9

From Coachella to Coca-Cola

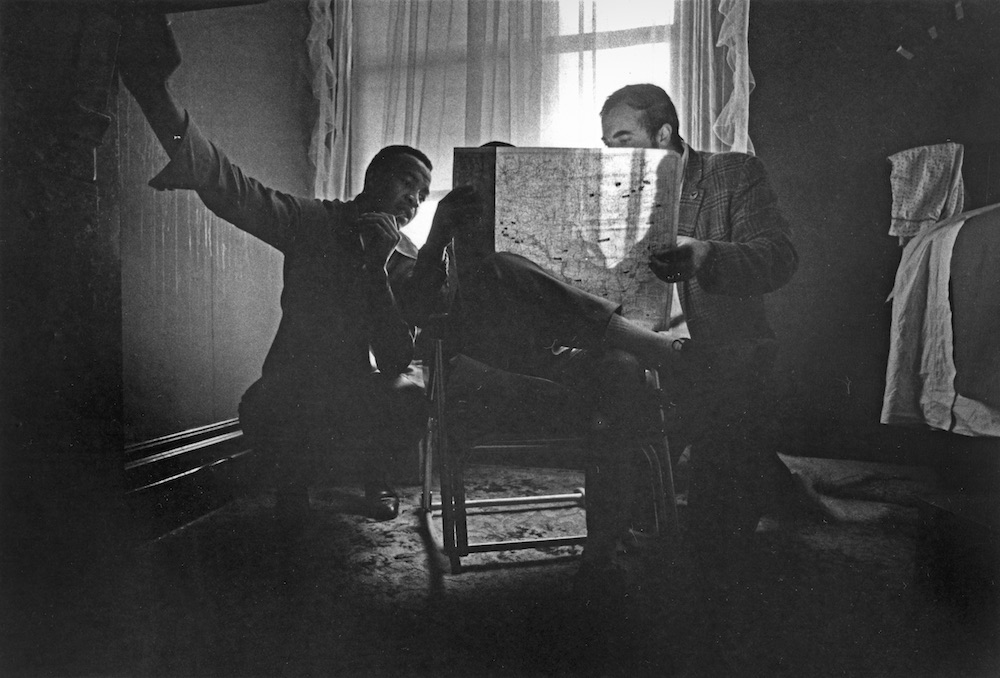

It was a hot day in Lake County, Florida, 1971. The orange harvest encompassed the winter months, but most days between November and May, winter meant merely hot and humid, rather than unbearably hot and humid. The orange trees were tall enough—about thirty feet—that they normally cast a long shadow on the dirt road beside them. That day, the shade was punctured by the red and blue lights of the Lake County Sheriff Office’s patrol cars. The cars were parked on the side of the road, creating a barricade between six Mexican American volunteers with the UFW and the several dozen Black workers that were harvesting oranges in the Minute Maid groves.10

UFW volunteers were there with union election cards, hoping to get a simple majority of workers to sign demanding union representation. The officers were there to arrest them the moment they stepped off the county road and into the groves, onto private property. The volunteers didn’t need to move. Workers stepped out from beside the trees, crossed the road, and took the cards to sign up themselves. In the following months, this scene would play out again and again across Central Florida’s citrus belt as Mexican American UFW volunteers from California drove miles across the sinkhole-pocked flatland of Central Florida, getting lost on unpaved backroads, visiting Coca-Cola-owned shantytowns, and signing up 76 percent of Minute Maid’s workers.11

Coca-Cola executives had seriously blundered and they knew it. This was the result. In 1960, only days after Thanksgiving, Edward R. Murrow’s CBS documentary Harvest of Shame broadcast the misery of Florida farmworkers into living rooms across America. That same year, Coca-Cola acquired juice producer Minute Maid and its Florida-based citrus groves and processing plants. Coca-Cola had been spared in Murrow’s exposé only because it had not yet established a strong presence in the state’s agriculture. In 1970, a decade later, it was the single largest citrus producer in the state, with thirty thousand acres of orange groves and nearly three thousand employees. Coca-Cola would not be spared that year when NBC broadcasted a follow-up to Harvest of Shame titled Migrant: An NBC White Paper. Workers living in company housing were televised, in full color, in dilapidated houses with no running water. A Minute Maid worker interviewed in the documentary put the conditions succinctly: “Right now, I don’t see no future.”12

The immediate result of the documentary was a congressional investigation into migrant farmworker poverty. Coca-Cola President J. Paul Austin was pressed by Senator Walter Mondale and the threat of a UFW-backed boycott into agreeing to allow collective bargaining agreements with a union. Winning collective bargaining agreements in California took the UFW nearly five grueling years of boycotts, strikes, and political pressure. Coca-Cola took a matter of months. After longtime UFW members and a half dozen local workers negotiated the contract, the union declared it “the best contract signed to date by the United Farm Workers.”13

The victory was not just unique for the UFW. It was also unique for the U.S. South’s farm-workers. Organized resistance by citrus workers had taken place in the 1930s and ’40s, when grove and processing plant workers under the CIO-affiliated unions walked out during harvest season in the thousands. At best, these demonstrations resulted in an increased picking rate for that one season. At worst, the organizations drew the attention and ire of Central Florida’s Ku Klux Klan, which opposed labor organization—especially among Black workers—and targeted CIO organizers as Communists. An unidentified Klan leader was quoted in the Tampa Tribune saying, “We know who the radicals are and we shall care for them in due course.” On the night of December 5, 1938, the Klan paraded four hundred members through the towns of Lake Alfred, Winter Haven, and Auburndale to intimidate workers into ending a strike. What made the UFW contract unique was simple: there was a contract, a three-year collective bargaining agreement with federally enforced arbitration. In place of temporary radicalism, there was the opportunity for permanent change.14

“A stumbling block”

Since joining the union in California, Mack separated from his first wife and married Diana Lyons, a white farmworker and early member of the UFW. Having proved their mettle in the fields, Chavez sent Mack and Diana to Florida to administer the Minute Maid contract. With “no job description,” a five dollar per week salary, and fewer than a dozen volunteers—a sympathetic lawyer, some freshly minted white college students, Black and Mexican American former farm-workers—Mack and Diana were expected to manage a contract of 1,200 to 1,500 workers. It had to be done across racial lines with Minute Maid’s “mixture of African- and Mexican-American, and white men and women.” And it had to be done among workers who, unlike in the California UFW, did not have a half decade of struggle and unionizing as common ground.15

The familiar tensions of the New South boiled under Florida’s sweltering heat, where the majority of Florida’s 150,000 to 200,000 migratory agricultural workers were Black. Many of them came from sharecropping arrangements on former cotton plantations in the Deep South, which were mechanized in the 1960s. A New York Times reporter predicted that race would be “a stumbling block” for the UFW in the citrus belt because its organizers were largely unfamiliar with Black farmworkers. And despite his childhood in Texas, including working in cotton fields, Mack demurred that “the only thing I know about the racial problem in the South is what I read in the paper.” Mack and Diana would spend 1972–76 working in the UFW Florida office in Avon Park, a Central Florida citrus town with racially segregated North- and Southsides and schools that had been integrated less than five years earlier.16

It was not that the United Farm Workers were aloof from the Black freedom movement. Far from it. Their grape boycott won crucial support along the East Coast from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC’s) Operation Breadbasket and in Northern California from the Black Panther Party. But those were examples of a multiracial coalition of otherwise discrete struggles. Chicago’s Operation Breadbasket supported the boycott because “there was an identification . . . with what Mexicans were going through.” But the UFW Florida office was unique. Here the UFW was not a Mexican American group cooperating or building coalition with a Black movement. This was the UFW’s best contract belonging to thousands of southern farmworkers, as many as 70 percent Black.17

“The Union is our Union”

If labor organizers had learned anything from decades of small victories and stubborn failures in the US South, it was that interracial unions were hard work. The UFW’s guiding philosophy for their unions was that the only way to make a contract function for workers was to ensure that workers took ownership of it. The same principle applied to interracial solidarity. If the only difference between having a union and not having one was a slightly larger paycheck, with everything else remaining the same, it would not work. That had been Mack’s view since the late ’60s. His model of what not to do was the Teamsters—set apart from workers, paid lavishly, dealing with the company over the heads of the rank and file. As one of the Florida volunteers said, “Unlike the Teamsters, we put the workers into administering every step of the contract.” For Mack and the Minute Maid workers, this bottom-up, interracial ownership of the union was based on three aspects of the contract: the hiring hall, steward election, and piece rate procedures. These were not Mack’s ideas, but the resolute insistence on them was.18

The day of a Minute Maid grove worker began early, when morning was still dark as night, and Florida’s humidity laid a heavy dew across everything—cars, grass, jackets. Work crews traveled by converted buses or piled into pickup trucks, either hired by a crew leader who contracted the workers as a self-interested intermediary between the grove owner and farmworker or with a group of their close friends and family. From Mack and the UFW’s perspective, the problem with these work crews was twofold: growers could stoke competition between crews, lowering wages for all potential workers, often segregated by race, so that grower-imposed wage competition became racialized. In place of crew leaders and self-segregated work crews, the UFW implemented hiring halls.19

The hiring hall was both a physical place and a concept embedded in the contract. As physical places, Mack described them as the buildings “out of which the contract is administered. Each hall also serves as a service center to help workers who are members,” and workers who were not members but might be soon. As the cornerstone of the contract, they functioned to subvert the role of the crew leader. Rather than hiring and firing crews at the company’s discretion, the company was required to send a letter to the union with the precise number of desired workers forty-eight hours before they were needed. The union would then assign workers based solely on its seniority lists. After the harvest, the company would send back a list of all workers, union and nonunion, with their hours and pay. The union supplied all the necessary workers; if the union could not supply the amount needed, only then could the company look elsewhere. As Minute Maid worker Ernest Fleming said, it was “the best part of the Union. It’s the best system that could be set up—it’s our hiring hall.”20

Within the Minute Maid fields, violations by grove foremen and supervisors were common, which required union stewards to be constantly on their feet. Foremen would list absent union workers as present and hired nonunion labor under the table, in their place, and pocketed the difference in wages. This had the unintended effect of breeding solidarity among union members. It meant stewards had to know the names and faces of everyone on their crews; they greeted and checked in with fellow workers, and noted whether they were there in the groves each morning.21

Florida’s citrus growers and their allies in the state legislature recognized the threat that hiring halls posed. Within a year, the Florida legislature introduced a “right to work” bill, HB74, intended specifically to undermine what a critic in the Orlando Sentinel derided as the UFW’s “compulsory agricultural union hiring halls.” With the UFW in mind, state Representative Lew Earle denounced “union monopolies and other enemies of free choice,” including hiring halls and closed shops, as violations of workers’ rights. This brand of union busting was common throughout the postwar South and Sunbelt. UFW stewards from Minute Maid testified in Tallahassee against the bill, “Now that I have the Union . . . there’s nobody that is going to take my job away from me or discriminate against me.” The UFW still pulled enough public sympathy and political sway that the bill was killed in the House subcommittee.22

Stewards were employees of Coca-Cola but represented the union in the groves. They were elected from among the work crews, which meant that stewards had to be, at the very least, likable. Stewards brought any problems from the crews—grievances, piece rate negotiations—to Coca-Cola foremen. For months after the contract was initially signed, stewards would take their problems to Mack, expecting him to solve them. Mack turned them away, insistent that if he took care of every problem in the groves the union would fail. The division between stewards, employees, and volunteers was always flexible, by design. UFW volunteers were practically mendicants, living on a meager salary of five dollars per week. A Florida volunteer remembered how Mack and Diana taught them to live on “peanut butter, bread, and apples,” sleep in their cars, and “shower” between long drives in rest stop bathrooms. It was common for volunteers to give up and work in the fields temporarily; the pay was better.23

Walter Williams, a lifelong farmworker, was a white steward elected by a crew “made up of about one-third Anglo, one-third Black, and one-third chicano workers.” In an interview with Diana, he admitted that on occasion there was a language barrier but said that “there are certainly no barriers to real communication.” The rhetoric invites skepticism, but stewards were answerable by vote to their typically multiracial crews. Black union member Ernest Fleming beamed, “The Union is our Union and we support it. One time some growers made it so that the Blacks didn’t get along with Browns and the Browns didn’t get along with the whites. Now we work just as one—just like a bouquet of flowers.”24

Picking oranges was different from working with grapes, sugar, or lettuce. Its biggest draw was that workers did not have to lean, squat, or crouch. Unlike the workers who harvested sugar or celery, they did not carry knives, which meant they had less chance to miss and accidentally tear into their own skin. What they carried when working with orange trees was a ten-foot or taller wooden ladder and a canvas bag to fill with as much as ninety pounds of fruit. Bouncing and swaying at a dozen feet in the air, they would reach into the tree, grab the orange in their one free hand, twist, and yank, dropping the orange into the bag that was slung over their shoulder. It was easy to lose balance and fall. A worker that fell from their ladder could break just about anything in their body that could be broken and be out of work for the rest of the season.

But it was not physical hardship that most incensed workers. It was the ways that foremen grifted them out of their full piece rate pay. Their canvas bags were emptied into boxes, the boxes emptied into tubs. Per the workers’ piece rate pay scale, tubs were supposed to hold ten boxes worth of oranges. But foremen insisted that workers pile the tubs with fruit so that that they held closer to eleven boxes. Correct tub counts were one of the first things that the union won in 1972 in grove after grove. Piece rates followed a similar principle. Before any worker picked a single orange, the crew steward would reach an agreement with the Coca-Cola foreman on a piece rate. This was intended to reflect the reality that some groves are harder to pick and have fewer fruit than others. Until a rate was agreed on, workers would remain stationary in the grove.25

“I may be poor and Black, but I am Somebody!”

Diana Lyons was white and educated. She had a bachelor’s degree in political science from California State University, Stanislaus, but she was not a “twinkylander,” as UFW executive board member Eliseo Medina called the typical white, college-educated, upper-middle-class ufw volunteer with no experience in farmwork. Before earning her degree, she had spent years working dairy farms and joined the union early, in 1966. In her first appearance in El Malcriado, she identified herself only as “a farm worker.” When she moved to Florida with Mack, she became the state’s boycott director and inherited a pile of responsibilities when Eliseo Medina and much of the boycott staff left Miami for California. In 1973, from her desk in the Avon Park headquarters, she penned a poem,

We’ve lived our lives as rented slaves

worked us into early graves

but that’s over now.

We’ve built a Union of our own . . .

built it with our blood and bone.26

Under Mack and Diana, the Florida Division embedded itself into the local communities, in counties whose entire economies depended on citrus. After Medina’s departure, the UFW opened its main Florida headquarters in an old funeral parlor in the Southside of Avon Park, a predominately Black neighborhood in Highlands County, one block from the railroad tracks, one block from the town’s historic Mt. Olive AME Church, and one block from a sinkhole-formed lake typical of the area. In addition to running the state’s boycott operations, Diana translated between English and Spanish for workers during meetings, phoned state representatives, helped write legislation, worked to get donations from local churches, and fought for a health clinic to be opened near the headquarters. In 1973 and ’74, while she was juggling all these tasks, she was also watching her and Mack’s young son, Rick Lyons, and attempting to get a UFW day care opened—for herself as much as for the workers.

The old funeral parlor was the hiring hall and service center for the area, which helped workers with translating documents, food stamp and welfare applications, and petitions to the city council. According to Avon Park volunteer Dorothy Johnson, the services they provided were admittedly “the type of work you would expect some government agencies to perform,” except that there were no such agencies, much less ones that did the work with “respect and dignity” for their clients. The centers helped with workers’ compensation, wrote letters for the illiterate, reported a family’s income tax, and even tangled themselves up in some divorce cases. UFW lawyers went over housing leases, pointing out inconsistencies and dates, and ensured that leases were compliant with Florida landlord-tenant law.27

Diana organized meetings in local Protestant churches across the citrus belt, attended by the congregation and interested public. She would sometimes become so impassioned that her remarks ran over her allotted time. She apologized to the pastor of Titusville’s First Presbyterian Church for having “taken so much time,” but explained that it was only because of “the urgency we feel for community participation.” Many churches responded positively and the themes bled into their liturgies; Westminster Presbyterian in Gainesville gave a sermon dedicated to the efforts of “America’s minorities to achieve freedom and dignity,” with a focus on farmworkers, comparing their struggle to the exodus of Israelites, an analogy familiar from the Civil Rights Movement.28

In Avon Park, with a population that barely cracked five thousand and a downtown that encompassed a few small blocks, a gathering of even a dozen people would have been noticeable. A gathering of more than a hundred, especially if they were Black, would have been an event. One of the services Diana organized during her first years in the area was a farmworkers’ summer camp for children with “simulations of strike and boycott activities, along with swimming, arts and crafts and games.” After normal summer camp activities, the children and their parents picketed the neighborhood Winn-Dixie supermarket in support of the California produce boycotts, and then marched to city hall to demand streetlights and markers, fire hydrants, and traffic lights for the Southside of town. The children chanted in front of city hall, “I am Somebody! I may be poor and Black, but I am Somebody!” The Avon Park City Council agreed to increase streetlights and safety markers. Mack Lyons was quoted in El Malcriado, “Maybe the Council members realize that once we get a taste of freedom, nobody can get away with treating us like slaves again.”29

“‘Negotiations’—and I use the term loosely”

Diana stood in the August sun, washing her and Rick’s clothing. Maria Barajas, wife of UFW steward Hilario Barajas, was nearby, preparing food. For more than a week they had lived and slept and worked out of their cars, which was normal for farmworkers. But they were not camped out in front of a grove. They were camped in front of Minute Maid’s headquarters in Auburndale, Florida. Two weeks earlier, Mack camped out on the lawn, fasting, consuming nothing but water. In response, Coca-Cola built a fence around the building. While Diana and Maria sat on top of their cars, they watched their children play in the grass, watched Coca-Cola workers come and go through the new gate. Another member, Joanne Francis, joined Diana and Maria and celebrated her daughter’s second birthday in front of the Auburndale office. She said, “A union contract is the only way we can provide for our children’s future.”30

They were there because the three-year contract with Coca-Cola had expired on January 3, 1975, and, as expected, the company was less than eager to renew it. After eight months of negotiations, about which Diana said, “I use the term loosely,” Coca-Cola and the UFW has been unable to agree on piece rate policy, hiring hall violations, discrimination against union members, and union volunteers’ ability to enter the groves. Now the contract could be lost as quickly as it had been gained. Mack and Diana were unable to use many of the UFW’s most effective tactics. They couldn’t strike. Mack predicted that doing as much would wipe out the union, as unionized workers would simply be replaced. The Florida office did not have the funds necessary to sustain a strike and the national office would not spare their resources on it. Threats of a Coca-Cola boycott were no longer taken seriously, for good reason: the threat was made nearly every month over the entire period of negotiations, but never materialized.31

Instead, Mack and Diana organized small-scale demonstrations, fasts, and sit-ins; and aired public accusations of racism in the groves. Mack invoked the language of Coca-Cola’s most famous advertisement against the company, finding that instead of “teaching the world to sing in perfect harmony,” they were “prompting discord in the fields.” Mack broadcasted his message in the language of racial solidarity, in contrast to what he deemed the company’s “paternalism,” “master-slave relationship,” and “massive discrimination in the fields against Black and Brown people.” While Diana camped in front of Auburndale, Mack drove to Atlanta in late August and sat in Coca-Cola’s corporate offices and demanded a meeting with J. Paul Austin, which never came.32

In California, the UFW had its hands full with three boycotts, strikes, and a legislative campaign. A Tampa Times writer interviewing Mack noted that “no direct confrontation had happened yet with Florida growers, because the “union’s manpower and money are being poured” into its California boycott campaigns. Mack accepted the situation and responded with a smile, “Once we get those over with, we’ll have some economic pressure to apply.” Reluctantly wary of mounting negative press, much of it from Mack, the company gave in, renewing the contract in November. But the union had been weakened. The limits of its large-scale organizational capacity were exposed and the fact that boycott and strike threats were empty now apparent.33

The negotiations were Mack and Diana’s last major success in Florida. In 1976, Diana traveled to Tallahassee to lobby for a sweeping agricultural labor rights bill in the Florida legislature, HB3095, modeled on legislation that the UFW had seen passed in California a year earlier. Despite Diana’s efforts and some support among liberal representatives, the bill did not even make it out of the House Agriculture Committee. It was struck down in front of a room Diana saw packed with sympathetic farmworkers. A Florida UFW volunteer argued that the failure meant the UFW in Florida now seemed “sparse and largely ineffective.” When the union arrived in 1972, Mack predicted boldly that the entire citrus industry would be organized under UFW contracts by the end of the decade. Instead, the union and its vision shrunk. No other companies were unionized. And in 1976, Mack and Diana were called back to Sacramento to lobby for legislation to fund California’s agricultural labor bill. The last time the Florida office received sustained attention in El Malcriado was in 1976. The union had not disappeared. It survived for two more decades, organized on the lines drawn by Mack and Diana, and only lost membership very slowly. But, confined to a single company, and without attention or backing from California, it was a labor union without a social movement. Success seemed to be an unreachably tall order, requiring conflicting commitments: the vision and resources of a national social movement, the rank-and-file commitment of workers ensuring economic justice on a daily basis, and a rootedness in local communities served by the union. Looking back on it twenty years after, volunteer Jerry Kay reminisced, “There, in and around Apopka, Florida, I saw not only what the [United Farm Workers] did to help the workers, but also what it could have become.”34

Terrell Orr is a doctoral student in history at the University of Georgia interested in agriculture, labor, and capitalism in the U.S. South and Latin America. His dissertation research explores the intertwined citrus industries of his home state of Florida and the state of São Paulo, Brazil.

Header image: An Indian River Orange Grove, Florida, Detroit Photographic Co. (publisher), 1898. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

NOTES

- “Mack Lyons to Curtis Rudolph, June 4, 1974,” box 1, folder 3, UFW Florida Boycott Records, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI (hereafter cited as UFW Records).

- Migrant and Seasonal Farmworker Powerlessness. Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Migratory Labor [. . .], vol. 8-B (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1971), 5459; “Lyons to Rudolph,” UFW Records.

- “A Young Union Leader,” The Movement, April 1967, 5; “Mack Curtis Lyons,” Obituaries, Chapel of the Chimes Oakland, accessed September 9, 2019, https://oakland.chapelofthechimes.com/obits/mack-curtis-lyons/; “Union Leader,” 5.

- “Union Leader,” 5.

- Detailed accounts of the AWOC and the Filipino American contribution to the farmworker movement can be found in Craig Scharlin and Lilia V. Villanueva, Philip Vera Cruz: A Personal History of Filipino Immigrants and the Farmworkers Movement, 3rd ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000).

- “Editorial: Enough People with One Idea,” El Malcriado, September 1965, 2, quoted in Lauren Araiza, To March for Others: The Black Freedom Struggle and the United Farm Workers (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).

- “Janis Peterson 1968–1990,” Farmworker Movement Documentation Project, University of California San Diego Library, https://libraries.ucsd.edu/farmworkermovement/essays/essays/059%20Peter-son_Janis.pdf (hereafter cited as UCSD Library); Peter Matthiessen, Sal Si Puedes (Escape If You Can): Cesar Chavez and the New American Revolution, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 155.

- Frank Bardacke, Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers (London: Verso, 2011).

- Miriam Pawel, “A Self-Inflicted Wound: Cesar Chávez and the Paradox of the United Farm Workers,” International Labor and Working-Class History no. 83 (Spring 2013): 154; Matt Garcia, From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 200.

- D. Marshall Barry, “Farmworkers and Farmworkers’ Unions in Florida,” Florida’s Labor History: A Symposium, Proceedings, ed. Margaret Gibbons Wilson (Miami: Florida International University Center for Labor Research & Studies, 1991), 43.

- Barry, “Unions in Florida,” 42.

- Hearings Before the Subcommittee, 5501; Migrant: An NBC White Paper, produced by Martin Carr (New York: NBC News, 1970). Documentary details can be found at http://www.peabodyawards.com/award-profile/migrant-an-nbc-white-paper.

- “Farm Worker’s Eagle Flys in Florida,” n.d., box 3, folder 36, UFW Records.

- Jerrell H. Shofner, “Communists, Klansmen, and the CIO in the Florida Citrus Industry,” Florida Historical Quarterly 71, no. 3 (January 1993): 300–309; “Klan Parades,” Tampa Tribune, February 27, 1947.

- Rebecca (Hurst) Acuna, “Memoir: UFW Volunteer/Florida 1972,” Farmworker Movement Documentation Project, UCSD Library, https://libraries.ucsd.edu/farmworkermovement/50th-anniversary-documentation-project-1962-1993/rebecca-hurst-acuna/.

- Jon Nordheimer, “Blacks May Be Stumbling Block,” Miami News, February 9, 1972. It was a New York Times news service report printed in the Miami News; “Union Leader,” 5.

- Lauren Araiza, To March for Others: The Black Freedom Struggle and the United Farm Workers (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014); Gordon K. Mantler, Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960–1974 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 226; quote from Calvin Morris in Mantler, Power to the Poor, 226; “Jerry Kay 1969–1975: Farmworker Union Memories,” Farmworker Movement Documentation Project, UCSD Library, https://libraries.ucsd.edu/farmworkermovement/essays/essays/065%20Kay_Jerry.pdf.

- “Jerry Kay,” UCSD.

- Bardacke, Trampling Out the Vintage.

- “Mack Lyons to Vivian Davenport, July 1974,” box 1, folder 3, UFW Records; “HP Hood Contract,” box 16, folder 23, UFW Records; “Listen to the Voices of United Farm Workers in Florida,” box 3, folder 21, UFW Records.

- “Mack Lyons to Harold Brondway, Dec. 26 1974,” box 2, folder 26, UFW Records.

- “Bill a Prop for Right to Work,” Orlando Sentinel, February 22, 1973; “Bill a Prop for Right to Work,” Orlando Sentinel, February 22, 1973; Mark Pitt, “Defeating HB74,” El Malcriado, April 20, 1973, 6.

- Barry, “Unions in Florida,” 48; Jayme Harpring, “My UFW Remembrance 1973–1975 Florida,” Farmworker Movement Documentation Project, UCSDiego Library, https://libraries.ucsd.edu/farmworkermovement/50th-anniversary-documentation-project-1962-1993/jayme-harpring/.

- Diana Lyons, “Florida Worker Turns Organizer,” El Malcriado, March 23, 1973, 16; Lyons, “Florida Worker,” 16; “Listen to the Voices,” UFW Records.

- Lisa Power, “Farm Laborers Plan Rally Against Policies,” Tampa Tribune, June 6, 1988, box 3, folder 18, UFW Records.

- Miriam Pawel, The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez’s Farm Worker Movement (New York: Bloomsbury, 2009), 207; Diana Lyons, “Some Untitled Thoughts on the United Farm Workers,” El Malcriado, November 30, 1973, 16; according to Pawel, the Florida boycott office was shuttered. Instead, the duties fell to Diana Lyons in her Central Florida office; Lyons, “Untitled Thoughts,” 16.

- Dorothy Johnson to Nancy Thomas, August 29, 1972, box 1, folder 1, UFW Records; “Violations and Arbitrations,” box 2, folder 29, UFW Records.

- Diana Lyons to Dale Heaton, December 4, 1974, box 1, folder 8, UFW Records; Samuel B. Trickey to Cesar Chavez, January 13, 1973, box 1, folder 8, UFW Records.

- “Farm Worker Children March in Florida,” El Malcriado, September 4, 1974, 7; “Residents Win in Florida, “El Malcriado, October 18, 1974, 2.

- “News Release, 8/2/1975,” box 16, folder 24, UFW Records.

- “Diana Lyons to UAWW Orlando,” box 2, folder 15, UFW Records.

- Jane Daugherty, “Labor Leaders Fast Continues,” Tampa Times, July 6, 1975; Daugherty, “Labor Leaders.”

- Daugherty, “Labor Leaders.”

- Chavez, Tampa Bay Times, April 26, 1974; “Chris Byrne to Mack Lyons, Nov. 18, 1976,” box 8, folder 5, UFW Records; “Jerry Kay,” UCSD.