Born and raised in the American South by a white Northern family, I have felt my experiences and identity straddle a line between the two, even while identifying with both. Growing up, my father took the initiative to teach and cultivate a deep appreciation of history and culture, taking the family to the many historical sites dotting the East Coast. Whenever my family visited a Civil War battlefield, my attention and interest were supercharged. My young mind could not get hold of enough information about this time when the United States was torn in two.

When I was nine years old, my parents divorced, and my mother later married a Black man. With a new family member in the household, I learned more about the Civil War from a Black perspective. It became clearer and clearer that the lessons I had been exposed to in school about the transatlantic slave trade and “states’ rights” were political measures wrought by the long arm of Lost Cause ideology.

When I was about ten years old, my mother and stepfather took my stepbrother and me to visit a reenactment at a battle site in the eastern part of North Carolina. We went to Averasboro Battlefield, one part of the Carolinas campaign in early 1865. My mother, who grew up in a Polish Catholic South Side Chicago neighborhood in the 1950s, wed a Black man born in the Bronx and raised on St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. His son from an earlier marriage, roughly my same age, became one of my best friends growing up, so much so that we would eventually call each other brothers, dropping the preceding qualifier.

We got to the battlefield at midday. There was a little bit of time to kill before the reenactment was to take place, so my mother and stepfather took us to the makeshift gift shop that had been set up in one of the older period buildings. I wanted a Union blue cap, and my stepfather happily obliged the store clerk at the checkout. My stepbrother was still in the shop with my mother while my stepfather and I exited the store to wait for them to settle on a souvenir and join us outside. I can still remember the look on my stepfather’s face when he saw my stepbrother come outside with one hand holding my mother’s hand and the other clasping a small Confederate battle flag.

“I wanted it. I like how the flag looks,” my stepbrother explained to my stepfather, whose expression was somewhere between utter disgust and complete shock, a look that I came to recognize quite well whenever someone said something he thought ridiculous or in bad taste. The feelings were tense between our parents, shown in a silence occasionally broken by my stepfather’s interjections of “Why?” and “What were you thinking?”

My mother should have known better. However, having spent her childhood school years in a Catholic school, I could imagine her curriculum may have skipped or inadequately covered the Civil War. I remember my stepfather having to explain to my mother what the Confederate flag represented to him and how it was ironic at best that my stepbrother was now holding that same flag. My stepfather ended up taking my stepbrother back to the store to replace his flag with some other souvenir, after which the flag was promptly deposited into the nearest trash can.

My family became stronger for tackling the issue and taking the time to resolve the problem. My family’s story is not unique—there are many similar stories among family and friends that illustrate the important and sometimes traumatic connections Americans can have to the Civil War.

Seeing a clear connection to how the past shapes who we are now has left me perennially wondering about each of our connections to the American Civil War and has led me to seek individual stories. I am driven by the powerful entanglement of the past and the present. This drive leads me to make images of visitors to American Civil War sites in hopes of revealing those powerful connections to a past that was and continues to be formative for our stories as Americans.

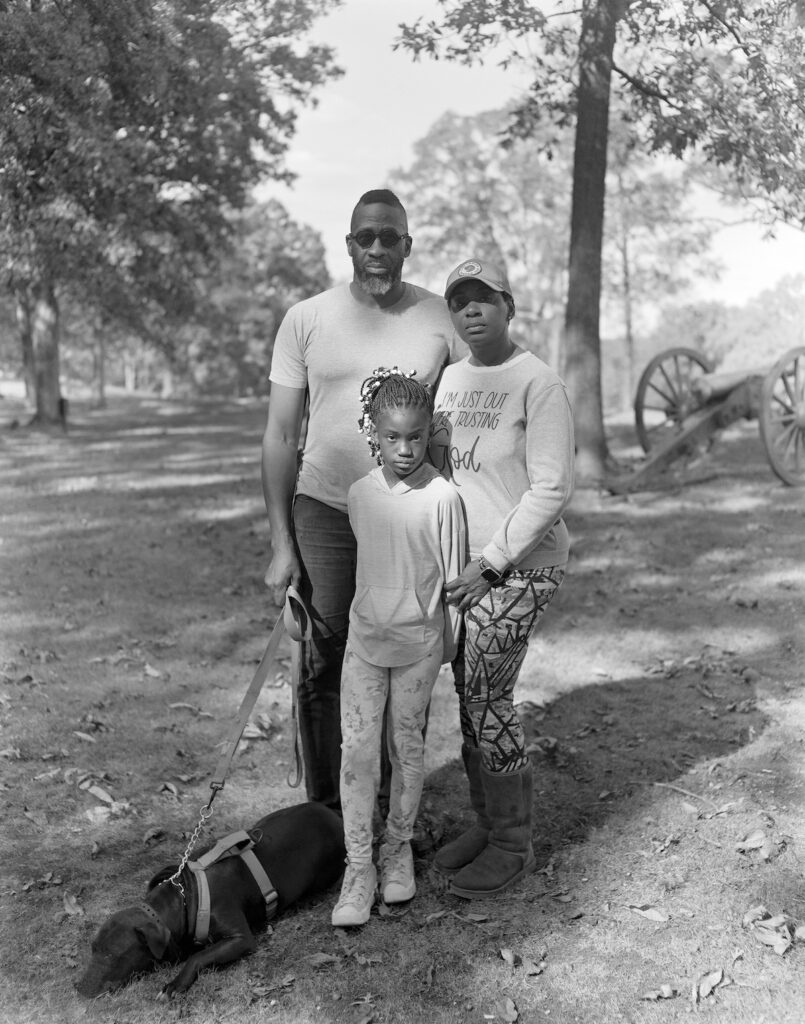

Ricky, Robin, and Kennedy, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 2022.

I learned that Ricky and Robin are military veterans who work in the DC area but live in Fredericksburg. Ricky and I spoke at length about the sense of gravity we both felt in these sacred spaces. Robin’s daughter, Kennedy, although appearing shy at first, produced an intense gaze that confronts both the viewer and camera.

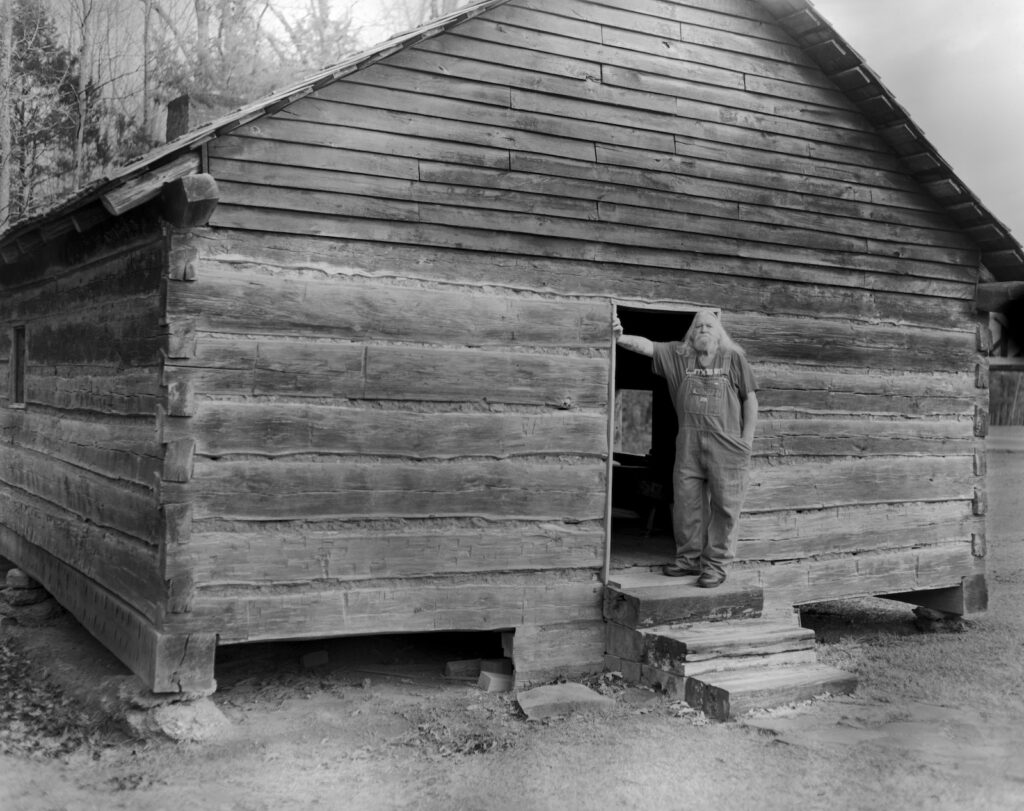

Scars, Tunnel Hill, Georgia, 2022.

Confederate reenactor from Sharpsburg, Maryland, 2021.

I did not pose or guide this reenactor. As soon as I asked if I could make his portrait, the reenactor instantly posed in a manner influenced by those seen at the time of the Civil War.

Figure at Tunnel Hill, Georgia, 2022.

After talking about the land and the events that took place here, Mr. Putnam (not pictured) produced a three-ring binder containing images of Civil War officers, but more pertinent to his life were the images of the mattress store his family owned in the area.

Self-described as “looking like an old Reb,” Shiloh, Tennessee, 2022.

I met this man just outside the Shiloh Church. He was standing to the side of the building as I watched him engage a few groups of visitors who walked up to peer inside. After speaking with him, it became clear that he was there to share stories—to hear and be heard, to see and be seen.

View of Bloody Lane, Antietam, Maryland, 2021.

Bloody Lane was one of the focal points of fighting at Antietam in 1862. The bodies of Union soldiers were piled on top of each other as wave after wave fell in front of this Confederate position, and the lane ran red with their blood. Today, the peaceful nature of these battlefields belies their darker histories and stands in stark contrast to America’s unhealed wounds that fester below the surface of our workaday lives.

Mindi, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 2022.

Visiting for the first time, Mindi expressed awe at what the soldiers on the heights overlooking Fredericksburg faced. She expressed doubt about how successful contemporary people might be in their stead.

Chickamauga hay, Chickamauga, Georgia, 2022.

The boundaries of protected battlefields often do not encompass the entirety of a site. The striking photographs of the battle’s destruction and carnage are sharply at odds with the image of a derelict gas station used as a stand-in for a hay barn.

Bentonville cut, Bentonville, North Carolina, 2023.

In these spaces I am constantly reminded of the visual metaphor of a strong line or fissure representing a historically divided nation.

Jacob, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 2022.

Jacob explained that his wife never joined him to tour battlefields due to their violent history. Jacob was now visiting these sites since his wife passed away.

Shiloh Church interior, Shiloh, Tennessee, 2022.

The interior of Shiloh Church presents with visible bullet holes from the fighting that took place during the Battle of Shiloh. These scars serve as visual reminders that even sacred spaces can and have been marred over the struggle to forge and make square our American ideals.

Long shadow, Totopotomoy Creek, Virginia, 2023.

By picturing visitors in these spaces and how they interact with memory and reflect on slavery’s legacy and the cost of freedom for everyone in our nation, I aim to capture the reverberations of the Civil War rippling into our time, as if to picture the long shadow the Civil War has cast onto today.

Vann Thomas Powell holds an MFA from Duke University and works as a documentary artist whose practice revolves around still photography and the moving image. Through a blend of historical and philosophical research, his work delves into the intricate interplay between past, place, and memory, with a particular emphasis on American identities. Powell is especially drawn to subjects such as foundation narratives, myths, tall tales, folklore, and seldom-told histories, seeking to unearth the layers of meaning embedded within these narratives.