“Nixon’s visit (only five months before his resignation) was seen by national journalists and politicos to be a trip to one of the few places where he would still receive a warm reception, and it was quite warm indeed. Nixon took the stage, played two songs on the piano, and bantered with Roy Acuff.”

As a genre of popular music, country music has never been as homogenous, stable, or traditional as both its critics and fans have often made it out to be. Even as far back as its commercial beginnings in the 1920s, country music’s multiple sub-genres and sonic diversity have defied easy categorization, and performers as well as fans rarely have fit the “hillbilly” stereotype that has long attached to the genre. The late 1960s and early 1970s, however, did find country music in a moment of considerable flux and potential consternation over whether the genre could maintain a coherent connection with its roots in the rural trappings and rustic performances of the early part of the American twentieth century. The country-pop Nashville Sound ushered in new instrumentation and production techniques—orchestrated violins, background choral groups, and smoother lead vocals instead of the fiddle, steel guitar, and twang of the previous eras—that made Nashville’s country music seem less “country” to some contemporary observers, who called for a return to what they saw as the genre’s true roots. In contrast with these extremely successful hits recorded on Nashville’s Music Row, country’s preeminent long-running live radio program, the Grand Ole Opry, resisted much of the change associated with the Nashville Sound, keeping acts who had performed for decades instead of catering to the new breed of country star, and retaining its traditional mix of comedy, tomfoolery, and song.

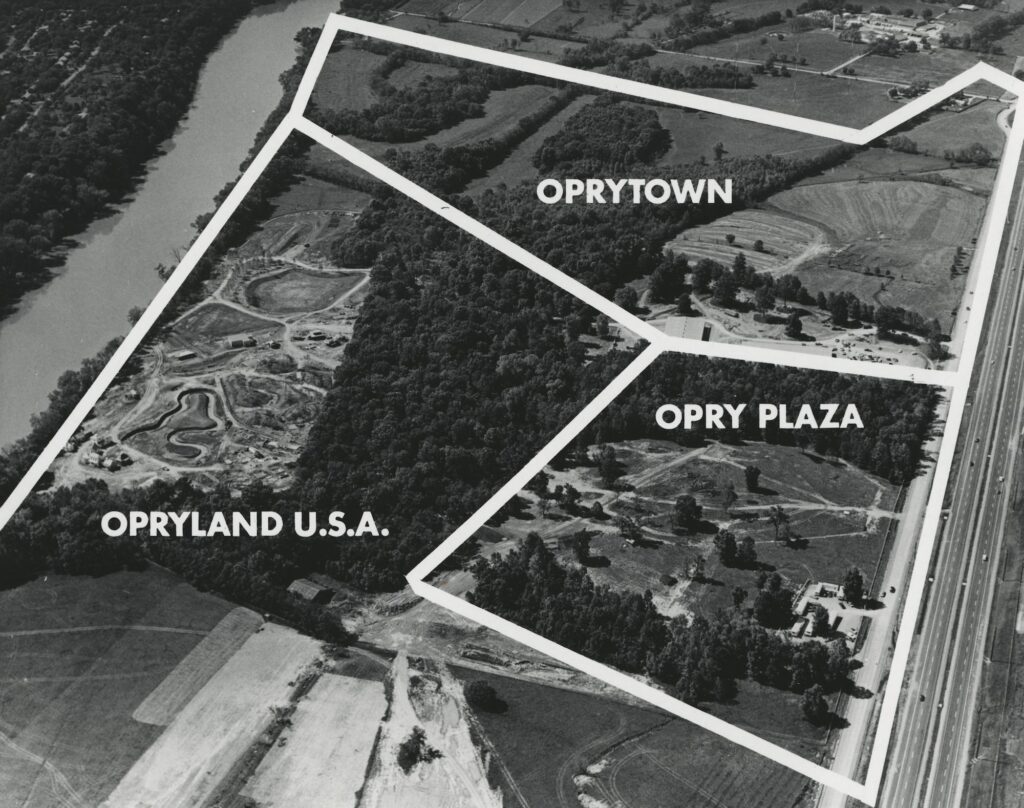

Because of the Opry’s inclination toward the traditional amid a season of change, the program had to delicately spin the 1974 decision to leave its home of over three decades, the Ryman Auditorium in downtown Nashville, for Opryland U.S.A., a new theme park complex outside the city limits, about nine miles from downtown. The size of the new complex—as well as its multiple commercial options, extravagant rides, and live animals—stood in stark contrast to the staid, cathedral-like old Ryman Auditorium. The Opry’s managers were aware that the live radio show’s historic location had been just as important as the list of performers who regularly plied their trade on stage every weekend. But the Opry’s corporate parent, National Life and Accident Insurance Company, envisioned the new park as something bigger than just a home for the Opry; they saw it as a chance to expand the Opry’s brand and generate revenue through multiple platforms.1

To justify the move from venerated older auditorium to expensive modern entertainment complex, Opry stars and leaders employed a two-pronged strategy. First, Opry figures drew on a potent national discourse about urban space and decried the “slums” of downtown Nashville to argue that the Ryman’s urban location was inappropriate for the Opry’s family-friendly audience and image. And secondly they argued that even though the Ryman had been “home” to the Opry for over three decades, what really gave a home its unique flavor was its inhabitants, and that fans and stars together would invest the new Opry House with the same down-home charm and character that they had brought to the Ryman. The rhetorical defense of the Opryland U.S.A. complex and the new home for the storied radio program drew on and perpetuated a larger matrix of beliefs and values about country music’s ability to retain traditional characteristics while still embracing modern accoutrements. As many scholars have observed, the commercial genre of country music has always generated much of its appeal by mediating the distance between the past and the present, the rural and the urban. The genre has provided a window onto the (oftentimes idealized) past and a vision of its rustic roots while also reassuring fans of their own acceptable modernity by locating the performances of rusticity within openly modern commercial ventures such as the Opry itself. When the Opry moved to Opryland, the new venue provided a platform for reconfiguring a notion of home and attachment to traditional places within this powerful dialectic of nostalgia and progress. Opry fans and stars argued that authentic country character was not bound to physical locations but to timeless country values and the preservation of a loving memory of old home places.2

How would an old-timey show run like a seemingly disorganized barn dance—what country historian Charles Wolfe has called a “good-natured riot”—translate to a comfortable, modern, climate-controlled, and spacious new theater? The question hovered over the debate about the move and the Opry’s final performances in the Ryman, but it was almost entirely outside observers who strongly critiqued the move or bemoaned the Opry’s rejection of its traditions. New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable scoffed at the notion that there could be a new Grand Ole Opry House, contrasting the “phony” Opryland Theater with the “real” Ryman. Garrison Keillor, writing in the New Yorker, pointed to the new complex’s inaccessibility for a writer without a car and instead gleefully chose to listen to the first show at Opryland on the radio in his hotel room. And outlaw country journalist Paul Hemphill dismissively referred to “an antiseptic new air-conditioned Grand Ole Opry House amid a hokey Disneyland-type complex called Opryland, U.S.A.”3

While these critics believed the Opryland development to be too commercial and synthetic, leading Opry figures argued instead that country music had finally gained the level of national recognition and respect that it deserved and that their new “home” at Opryland was both the proof of this and the best way to showcase their modernity to the world. This sentiment found expression in a phrase commonly attributed to singer/songwriter Tom T. Hall and repeated by a number of Opry stars at the time of the move: “They’re taking us out of the barn and into a home.” Hall’s analogy presented the old Ryman Auditorium as no longer sufficiently modern enough to house the Opry, and the new complex at Opryland as a more appropriate and welcoming home for the program and its fans. The barn was to be remembered and cherished, but only as a nostalgic totem of lifestyles often celebrated in country music’s memory but not always lived by the people of country music. The word at the heart of Hall’s declaration, “home,” was central not only to country music culture but to the political culture of the 1970s as well. This spatial and ideological re-positioning of the Opry emerged out of a larger cultural trend within country music which helped to normalize the previously stigmatized genre and its fans, locating them in the geographic and temporal mainstream of American life—suburban, not inner city; late twentieth century, not late nineteenth; and more national than regional. In addition to the rhetorical defense of the new Opry venue, liner notes and song lyrics from leading country figures, such as John Loudermilk, Charley Pride, and Tom T. Hall, employed a discursive strategy that privileged the people over the home. The move away from the Opry’s home for over three decades resonated with cultural ideas and anxieties about country music’s much more longitudinal shift towards suburban middle class consumers and values. Country music had been trying to shake the hillbilly stereotype for decades and in the early 1970s the language of conservative populism and a suburban ideal of “home” (specifically counterposed to the purportedly unruly inner city) made the most sense as a strategy to evoke and then inhabit the American mainstream.4

Although the Opry’s move out of the Ryman in 1974 was greeted with the bittersweet tears of leaving a childhood home, the Ryman had in fact not always been the home of the Opry. The program changed venues several times in the first decade and a half of its run. But in 1943 the Opry found a home in the city-owned Ryman Auditorium, where it would stay until 1974. Despite a history of grudging acceptance on the part of Nashville’s elite, by the mid to late 1960s, the country music industry was supporting Nashville’s economy, and the city institutionally supported the industry by emphasizing its potential to increase Nashville tourism. In particular, the city recognized that most Opry visitors came from outside of Nashville, and they brought their tourist dollars with them.5

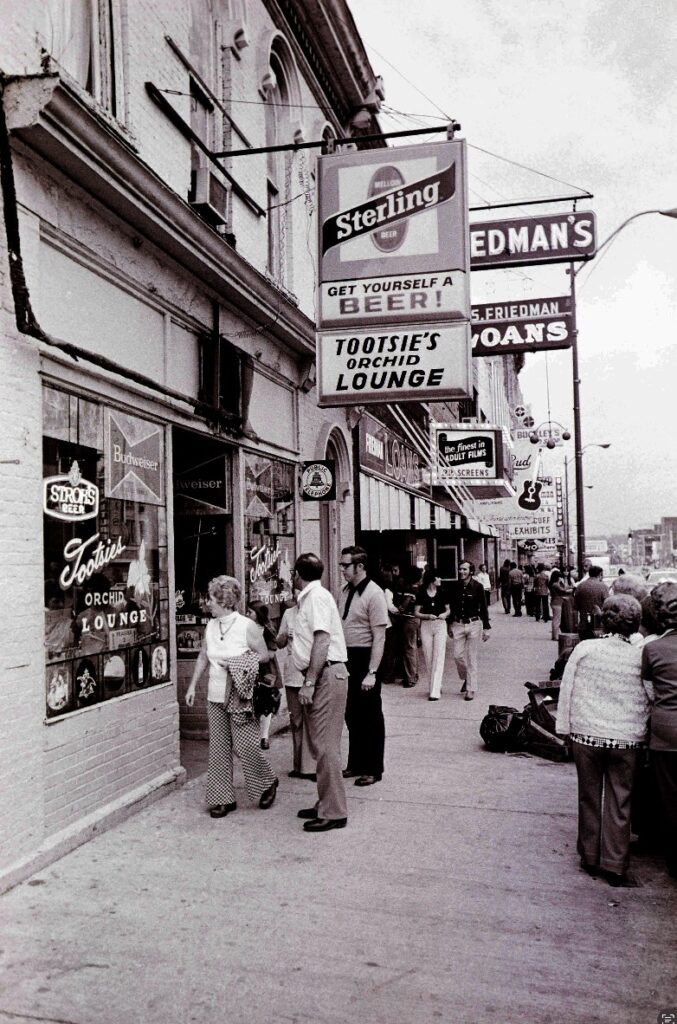

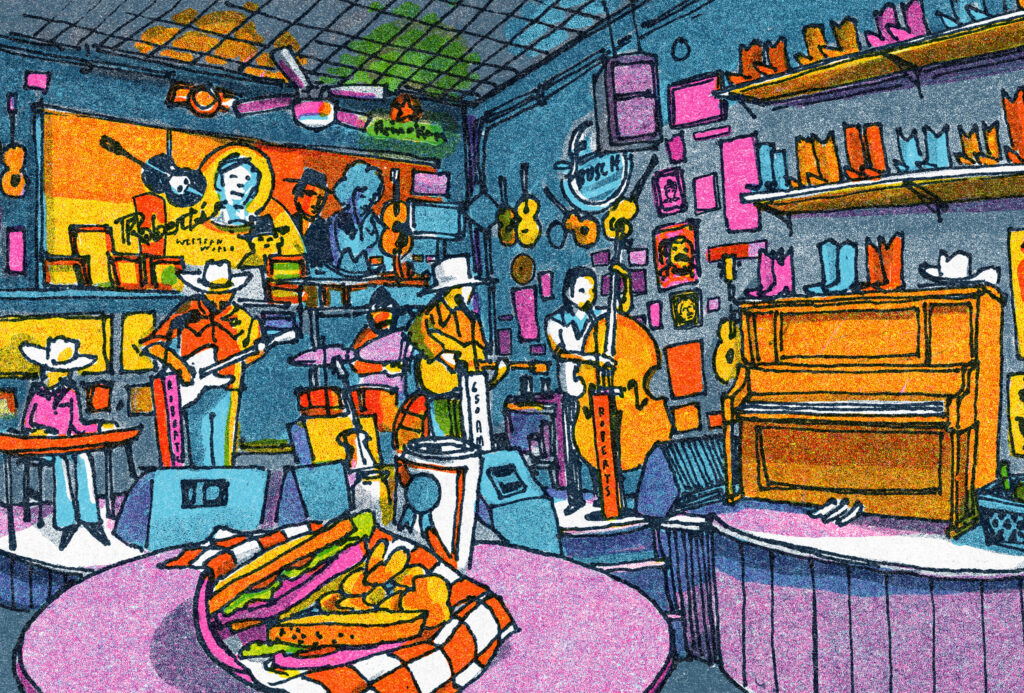

Fans generally spent the afternoon ahead of the show shopping, eating, and drinking in Nashville’s downtown establishments (like Linebaugh’s restaurant and Ernest Tubb’s Record Shop), expanding the ritualized space of an Opry visit to include not just the Ryman but the surrounding downtown blocks. Before the show, fans waited in lines that stretched around the corner on to Lower Broad, the neighborhood’s primary commercial strip. By the late 1960s, Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, whose back entrance abutted the Ryman’s own back entrance, had become a world-famous watering hole for Opry stars before and after their sets. As a result, Opry fans frequented Tootsie’s and other hot spots in hopes of an up close and personal glimpse of their favorite stars. The density of downtown development facilitated this easy access to multiple retail sites and created a festive atmosphere on show days, but it also created a more unpredictable heterogeneous space.6

Despite this thriving scene on Opry nights, however, downtown Nashville was subject to the common pressures of suburban development and the increasingly negative cultural markers attached to urban space. Cultural urban historians have shown that over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, retailers, investors, government officials, and journalists across the nation all believed downtown was under siege from “blight” and “slums,” while popular culture imagined “the city” as a place of crime, poverty, and disease. In tandem with these prevailing cultural ideas, the development of suburban office and retail centers threatened the profits of downtown businesses and Nashville retailers and city officials alike worried about the neighborhood’s future. In the late 1960s, these downtown retailers and developers looked to urban renewal as a way to revitalize the area and combat the flight of shoppers to the suburbs. One design firm, explicitly recognizing the importance of the Opry to Nashville’s economy, proposed including a Performing Arts Center in their plans for a joint public-private redevelopment of the downtown area. Thus, it was entirely conceivable that the Opry could have found a way to remain a central piece of Nashville’s downtown. However, the program’s corporate stewards at National Life had other, more ambitious ideas.7

The Ryman Auditorium, built in 1890, was in major need of structural renovation, for reasons of both safety (reinforcing and fireproofing) and comfort (air conditioning and newer, more comfortable pews). WSM president Irving Waugh researched the financial investment needed to make the auditorium fire-resistant, improve air conditioning and heating, and expand the site itself to provide more space for dressing rooms for the stars and offices for WSM. Waugh determined that rather than investing in the auditorium just to maintain a show which ran only twice a week and had no other major mechanisms for generating profit, it would be more sound to invest in a larger complex of facilities that would allow WSM to capture more of the Opry visitors’ tourist dollars, as well as bring in visitors who were not Opry fans. In order to achieve this, National Life needed a large plot of land and the ability to control and regulate the space.8

Access and Control

The language that the Opry’s visible leaders deployed revealed the extent to which the Opry stewards perceived, or attempted to portray, the downtown space as “under siege.” Opry leaders used the words “protect” and “control” to valorize the new suburban site over the unpredictable downtown space. In 1975, Opry star Roy Acuff wrote in his introduction to journalist Jack Hurst’s book on the Opry: “We are now in a beautiful spot at Opryland, and we have enough land out here to protect it.” Hurst quoted WSM president Irving Waugh in the same book: “We decided that instead of rebuilding down there we should go outside the city to a place where we could control our own environment.” Waugh insisted they had to go “outside the city,” suggesting that it was not just downtown that was unsuitable, but that there was no urban space that would allow them to protect and control Opryland the way they wanted to. Suburban values meshed with suburban land opportunities.9

National Life bought a total of 369 acres but only used 110 for the actual development of Opryland, leaving a buffer zone around the park—what the official National Life press release referred to as “sufficient acreage to provide for the Opryland park itself, parking, and enough additional area to permit control of the park environment.” The “additional area” had no necessary park function but allowed WSM to control the visitors’ entry and exit to Opryland. This was a major change from the space of the Ryman, where “unprotected” visitors waited in lines on the street and in nearby alleys.10

Opryland provided National Life with the opportunity to control not just the park but its surrounding commercial space as well. At the time of purchase, the Opry’s new neighborhood contained a combination of undeveloped rural land and new residential construction for relatively affluent white suburban families. With the Cumberland River on one side and the newly minted Briley Parkway on the other, the future site of Opryland was well protected from encroaching development. The spatial arrangement of the complex established a buffer zone around the ring of the park to separate the visitor from the outside world, and the planners designed the park itself as a kind of surreal fantasy land to further distance the visitor from any particular kind of spatial associations. WSM and National Life, knowing full well the importance of the Opry’s “authentic” setting, went to great lengths to sell the new Opryland as a natural, realistic environment. Their initial press release stated, “The entire Opryland U.S.A. complex is alive with naturalness. There is NO animation. Instead, the total flavor is one of reality from live buffalo roaming the range to honest to goodness American antiques used throughout the scores of buildings.” Opryland’s stewards intended to retain “real” elements of the actual country, including open spaces, live animals, and real trees, while fairly openly merging modern amenities, including a parking lot for 3,800 cars and a dedicated retail complex called Opry Towne. This kind of large undeveloped and controllable space was simply unavailable downtown.11

The “slums” and Moral Anxiety

The Opry’s decision to leave downtown Nashville and move to a new suburban retail and entertainment complex transpired in the context of urban disinvestment and explosive suburban development. Racially inflected understandings of these demographic changes have often played out in discussions of crime and safety, and it was no different for Nashville and the Ryman. Country stars cited fan safety without mentioning specific crime or danger, instead using the term “slums” to describe the Ryman’s neighborhood. This subtle intimation of danger and undesirable “others” worked to justify the move without the need for explicit evidence of crime and danger in the era of “white flight.” The invocation of slums could suggest, as if it did not even have to be said, that the suburban Opryland area was simply “nicer.” Physical danger, economic distress, and moral laxity were bound together in a general sense of undesirability which Opry figures loosely used the term “slum” to invoke. Opry veterans Acuff and Hank Snow both used the term “slum” to disparage the neighborhood, and Vic Willis ominously suggested, “Thank God we’re getting out of here. They should’ve built a new Opry House 49 years ago. They talk about atmosphere encircling this place. Well, let me tell you something. We don’t need this type of atmosphere.” Though its unclear precisely what atmosphere Willis fears, his use of the word “encircling” resonated with the notion of the slums as a “ring of blight” surrounding the nation’s downtown areas.12

Porter Wagoner’s criticism was more pointed. He focused on the alley between the Ryman’s back door and Tootsie’s Lounge, a previously celebrated aspect of the Opry’s environment, which famously facilitated star-fan interaction. Wagoner’s testimonial for WSM emphasized the seediness of the Opry’s location and the need for a family-friendly venue for fans: “We will have vastly improved parking facilities and better access to the fans, rather than meeting them in a dark alley. The entire complex is safe for the children and the whole family.” Wagoner focused on the “dark alley” between the Ryman and Lower Broad businesses, even though the Ryman was actually surrounded by retail businesses which drove a great deal of concentrated pedestrian traffic. In an oral history recorded the following year, Snow echoed Wagoner, claiming, “But the good point . . . is that we got out of that alley. We got out of that which actually is known as really the slums of the city, until they clean it up a little more.” Snow went on to mention the lack of dressing rooms, parking, and air conditioning, but the “slum” location of the Ryman was, for him, the first strike against the old Opry. His disdain for “that alley” revealed an urgent desire to leave downtown.13

Proponents of the move did not limit perceived threats to physical ones; leading Opry figures also warned of the moral hazards of downtown Nashville’s commercial amusements. Acuff in particular frequently referenced the combination of drinking establishments, X-rated movie theaters, and “massage” parlors, as not in keeping with the Opry’s image and its fans’ sensibilities. Acuff told an interviewer six months after the move, “So many of the undesirable types of establishments got up around us down there. It went from a beer joint to a drink joint to the rubbing parlors, and all the different things of sin.” Acuff owned property around the corner from the Ryman, so his interest in the condition of the neighborhood may not have been purely confined to the Opry’s image or the fan experience, but even so his pronouncements speak to the character he expected the Opry to exhibit. Acuff’s disdain for the drinking joints of Lower Broad hardly squared with country music’s lyrical content over the previous decades, which frequently presented social life in terms of a hedonist Saturday night/penitent Sunday morning dualism. Historically, both sides had a place in country culture and worked together to create country’s unique appeal. But Acuff’s emphasis on the importance of “family” to the Opry’s sense of “home” suggested that the connection between privatized suburban space and the dangers of the city were crucial to the construction of Opryland U.S.A. as a better “home” for the Opry, its fans, and their families.14

The Opry’s New Home

The move from an “undesirable” inner city space to a new suburban development may have seemed wholly intuitive for other industries in the late 1960s, but in abandoning the venerable Ryman the Opry grappled with resistance to change and the fact that much of its appeal stemmed from the show’s maintenance of tradition (even as fans and performers alike were very aware of the performative aspect of the Opry’s traditional facades). Country music fans and performers have always been savvy about the performative aspects of the industry within its setting as a wholly commercial entertainment form. But Opry leaders understood that when fans and critics referred to the Ryman as a “tabernacle” or “mother church” they invoked not just the auditorium’s early history as a home for religious meetings but also the theater’s central, even sacred, place in country music culture. Therefore, National Life and WSM intended to minimize the extent to which they discussed the Ryman and instead focus on the spectacular new facilities which they believed the Opry so richly deserved. Opry manager Bud Wendell emphasized that the show would remain exactly the same and described the move as a simple “lift and place” procedure: “What we’re planning to do is simply lifting it out of the Opry House and putting it into more pleasant surroundings.” In fact, WSM and leading figures literally lifted a circular piece of the Ryman’s stage out of the old Opry House and transported it to the new theater so that Opry performers could still sing on the sacred ground of the old place.15

This literal preservation of a piece of the old stage in the new theater signaled an intention to maintain Opry traditions and values, but it was the stars and fans together who provided a more nuanced narrative justifying the move and reassured skeptics that the Opry would continue to value tradition, memory, and family. Opry figures argued that, like any home, the true life of the place came from the people who lived there, and the show and its fans would not lose their unique down-home sensibility in a modern expensive theme park complex such as Opryland U.S.A. As Opry star Jean Shepherd told the Nashville Banner, “The new place is gorgeous, but it makes you wonder if you can kick your shoes off out there. But you know Jean Shepherd, I kick my shoes off wherever and whenever I feel like it.” Shepherd first raised the fear that behavior at Opryland would have to be more ordered and regulated, but then very quickly dispelled that fear. She instead suggested that the Opry’s relaxed and intimate character would remain intact despite all the money that was poured into the convenience and technology of the place. Her willingness to “kick off her shoes whenever she felt like it” transcended what disapproving country journalist Paul Hemphill referred to as the “antiseptic” nature of the new space.16

Testimonials

The same set of Opry star testimonials that WSM circulated in defense of leaving the Ryman also contained passionate support for the new Opryland complex. Many stars emphasized that the new venue was unequivocally superior and fans and performers alike would be more comfortable and happy at the new place. Minnie Pearl summed up the feeling well: “There is always a certain sadness connected with a move from an old place to a new . . . The most important factor, as I see it, is the comfort of the fans. The fans are the Opry—the most important part of it—and they have certainly been uncomfortable in the old house. Now, they’ll have comfortable seats, air conditioning, plenty of room and a space to park, plus other advantages.” The bond between fans and performers was central to this understanding of the importance of the new park: the fans had to be comfortable in order to play their role in co-constructing the authentic Opry experience.17

Fan club newsletters in turn celebrated and supported the new complex. Fan club newsletters from the time of the Opry’s move indicate fan awareness of opposition to the new theater complex (most noticeably, that the technologically advanced and expensive environment of the new theater would change the Opry’s intrinsically spontaneous “down-home” nature) but echoed Jean Shepherd in minimizing the change in location. They presented a narrative in which slightly dubious fans almost immediately realized that the spirit of the Opry would survive any change in venue. A Tex Ritter fan wrote, “despite all the mechanization and new-theater respectability, Cousin Minnie’s ‘HowDEEEE’ carried with it an unmistakable message—the Opry might have moved, but it will stay down-home.” “Down home,” here, was clearly not tied to any geographic or structural space: the continuity of Pearl’s distinctive greeting still fully signified “down home” in a modern suburban entertainment complex.18

The president of a Loretta Lynn fan club paralleled this quick dismissal of any fear that the Opry had changed, “We had been a little anxious about whether the old mass-of-organized-confusion type setting would be banished with the move from the old Ryman. How delighted we were when the curtain went up that evening and there was the same old everybody-running-around, talking, and joking and just a general air of unorganized fun and brotherhood!” She went on to emphasize the fact that the people mattered more than the material space of the home: “No, the Opry hasn’t changed. The HOME of the Opry is the only change and believe us, it is only for the better!” According to these fans, Minnie Pearl’s possibly disruptive “HowDEEE” and the general air of unruliness which were hallmarks of the Opry followed it easily to its new expensive environment.19

Despite the potential controversy, most Opry performers agreed. Shortly after the Opry’s debut at Opryland, Country Music Foundation writer Patricia Hall interviewed Opry star and pianist Del Wood about the new theater’s character and atmosphere, suggesting perhaps that the show should never have moved. Even while admitting that she had only once been to the Opry, Hall asserted that moving from the Ryman to Opryland was like “moving from a great old Victorian house into one of these new plastic apartments.” To Hall’s biting critique, couched in terms of contemporary architectural complaints, Wood promptly responded by pointing to the Ryman’s cramped dressing rooms and inadequate restroom facilities, suggesting that, for the performers, access to improved facilities trumped the ramshackle charm of the old Victorian place. Wood then further explained her willingness to leave the Ryman behind and provided a cogent analysis of nostalgia for childhood homes:

If I could go back to my home and my grandmother and my daddy could be there, who are both now gone, and my mother, and we were all young again, oh, how wonderful it would be. But we can’t do that. We must take what we have now, and what we have now is the family we have left, and this is true at that new Opry House.

Reminding Hall that country music must live in the present and not the past, Wood suggested that the feeling of home that the Opry provided would be just as authentic, if not more authentic, at the Opry House, even if it did remind Hall of “one of those plastic apartments.” By drawing the comparison with her own childhood home, Wood metaphorically aligned the Opry’s geographic history with that of many of its fans who had left their own childhood homes behind.20

Several of the Opry stars’ testimonials collected by WSM at the time of the move echoed Wood’s sentiments. Fifteen-year Opry veteran Archie Campbell said, “But most important, amid all this change, one thing will stay the same—the people . . . Up in Bull’s Gap, where I come from, there’s a saying: ‘It ain’t the house that makes a home, it’s the people that live there.’ We’re just moving to a new home.” Much as the Loretta Lynn fan club president took pains to emphasize that the home of the Opry would be the only thing to change, Campbell’s use of “just” minimized the specifics of any particular home and prioritized the inhabitants instead. Country comedian Jerry Clower further tied the Opry’s move to a larger cultural shift with a statement that fully supported moving forward, not looking backward: “My home is not like it used to be, my church is not like it used to be, my car is not like it used to be—in fact, I can’t think of much that is.” These Opry stars foregrounded their own modernity (against the stereotypical assumptions to the contrary), and their acute awareness of the changes in the world reassured fans and cultural critics that the Opry would stay the Opry in the new suburban theme park complex. But like Clower’s home, church, and car, it was understood that the Opry might not be quite like it used to be.21

Despite moments of scattered apprehension about the move to Opryland, by the time of the actual move the Opry community was publicly behind the new place and the theater’s status as the new home of the Opry. The rhetorical defense deployed by WSM and the Opry stars had worked. The discourse surrounding the opening of Opryland as the new home for the Opry succeeded because it resonated with an ongoing re-thinking of country music’s socio-spatial place in the American imagination. In 1973, President Richard Nixon tapped into this discourse when he declared, in proclaiming October as National Country Music Month, “Now the term describes not just a locale but a state of mind and style of taste, as much beloved downtown as on the farm.” Nixon’s description of country music as a state of mind referenced two seemingly spatial opposites (downtown and the farm) but ultimately downplayed the importance of geography, instead emphasizing temperament and taste. This formulation mirrored the discourse employed by Opryland’s defenders. Nixon’s support for the ideology of the Opry reached its ultimate expression when he visited the new Opry House on its opening night, officially endorsing the new location. (The Ryman had never hosted such a prestigious Opry visitor.) Nixon took the stage, played two songs on the piano, and bantered with Roy Acuff. The triumphant industry press coverage trumpeted Nixon’s visit as further proof that country had arrived and been validated.22

Country “Homes” Outside of the Country

The spirited defense of the new Opry theater resonated with the ideas produced by and about country music in the early 1970s that relegated agrarian lifestyles and iconography to a fondly remembered past, even as country figures successfully retained their country values in modern homes and situations. In the Grammy-winning liner notes to his 1967 album, Suburban Attitudes in Country Verse, John Loudermilk normalized country fans’ middle-class consumption patterns and suburban residence, while asserting that their traditional values had remained intact. He argued that a subdivision of suburban homes could be the new location of country homes and opened his essay by suggesting: “If you don’t believe it, just go out Interstate 65 to Exit 19, drive on through Brentwood, and between the shopping center and the country club you’ll find an entire village of country houses. John D. Loudermilk’s is the forty-eighth, three-bedroom brick on the right.” Here Loudermilk strikingly elevated suburban tract housing (with the typical suburban hallmarks, the shopping center and the country club) to the level of “country homes,” suggesting, as the defenses of Opryland would seven years later, the powerful portability of the country home.23

The essay further used wordplay and inversion to take traditional elements of the country stereotype and argue that country people were now middle-class consumers, not rustic throwbacks from a bygone era. In a tone typical of his essay, Loudermilk admonished an imagined visitor:

Talk about the weather, sports, flying saucers, anything but farming. If you ask him how’s the crop doing, he’ll tell you fine but they’re about to drive the good wife out of her skull. {Their ‘crop’ being three young sons . . . who are country boys, too.} If a wagon pulls up outside, don’t look for the horse. He’s under the hood with the rest of his 249 brothers.

Subverting key elements of the rural stereotype to provide a different, more contemporary meaning (a “crop” of children in a station wagon), Loudermilk argued against the outdated understanding of “country people” as farmers still relying on horse-drawn wagons. Even though country music fans had been enmeshed in urban and suburban social worlds for decades, Loudermilk still felt the need to address the stereotype in 1967. Loudermilk established that although the outward trappings of many rural-rooted people had changed, their core values had not, despite, as his album’s title suggests, a shift to suburban attitudes (and spaces). What made them “country” was not living on the farm but retaining traditional values—and it was these enduring values in the face of homogenization that made suburban country fans unique:

They believe kids ought to be thanked when they do good, and spanked when they don’t. They know tears are just as normal as laughter and they’re not ashamed to do either in public if they feel like it. Why, these corny country hill people have even been known to say family grace in a public restaurant. Yea, when you think about it, I guess country people are a different breed after all . . . especially nowadays.”

Here Loudermilk slyly returns to the stereotypical understanding of the “corny country hill people” only to trumpet their unwillingness to give up their traditional (what may seem too corny to some modern people) values.24

Charley Pride took the idea of country’s portability even further with his 1970 No. 1 single, “Wonder Could I Live There Any More.” Like Loudermilk, Pride emphasized and even celebrated the fact that his rural ties were a thing of the past. The song deconstructs the romanticized mythology of country living by showing instead the combination of hard work and hard times associated with living “there.” Each verse takes a specific piece of an idealized rural past and questions whether anyone would trade in the comforts of modern life for the hard work and economic uncertainty of the past. In the opening verse the narrator invokes a pastoral image of an early morning rooster call but quickly shifts the focus to the number of chores that need to be done in the course of “another hard work day.” The chorus then suggests, quite happily, “It’s nice to think about it / maybe even visit / but I wonder could I live there anymore.” The song firmly locates the narrator outside of the country and actually takes a strong stance against the country as a viable site of anything but nostalgia—by suggesting that the country is only maybe nice to visit. While ambivalence about “the country” certainly can be found in earlier songs, a No. 1 single that so forcefully rejected the country life in the present day (finding pleasant feeling only in memories of the past) was unprecedented.25

The song featured elements of the new Nashville Sound—the requisite background group supplemented Pride’s vocals at the end of each verse and into the chorus, and the song’s beat carried it forward without traditional country sound signatures like mournful steel guitar or fiddles. Pride celebrated his distance from the country life by using a musical style, the Nashville Sound, associated with country’s push to be recognized as a more modern form. Pride’s description of the hardships of rural life paralleled the decision to leave the uncomfortable and potentially hazardous Ryman Auditorium (I Wonder Could I Perform There Anymore?): why put up with inferior conditions when you have achieved the means to provide yourself and your family the best possible accommodations?

As mentioned earlier, Tom T. Hall encapsulated much of the sentiment around the Opry’s move with his celebratory line, “They’re taking us out of the barn and into a home.” That same year he recorded a number one single, “Country Is,” which further deepened this notion that country was not fixed in space but a state of mind, and that a country home could be constructed anywhere. The song opens with conventional rural imagery by declaring that “country is” sitting on the back porch and listening to the whippoorwill. Two verses later, however, “country” has moved out of the country and become “living in the city/knowing your people/knowing your kind.” As the song progresses, country becomes not any place in particular but instead “what you make it . . . all in your mind.” Finally, as in Loudermilk’s liner notes which reference traditional parenting and the importance of honest emotions, Hall’s speaker declares that “country” is all about values: “working for a living, thinking your own thoughts / loving your town, teaching your children / finding out what’s right and standing your own ground.” As Hall says of country in the final verse, “it’s all in your heart.” This declaration fully resonated with the justifications and celebrations proffered by other Opry stars who endorsed the program’s move out of the Ryman into the gleaming new theater inside the Opryland U.S.A. theme park complex.26

Conclusion

In 1994, twenty years after what was presumed to be the last Opry performance in the old “Mother Church” of country music, the Opry’s new owners, Gaylord Entertainment, completed an extensive renovation of the virtually unused Ryman Auditorium. The urban “revitalization” of the late 1980s and early 1990s had made the downtown neighborhood a more attractive investment option, and Gaylord began renting out the Ryman’s renovated space for a variety of events several nights a week. After the venue had operated as a general performance space for three years, the Opry experimented in the late 1990s with returning to the Ryman during the winter. This tradition continues today, and from November to February the Opry broadcasts out of the Ryman, just as it did thirty-five years earlier.27

Changes were afoot out at Opryland as well. Declining attendance numbers led Gaylord to close down the theme park piece of the complex in 1997 and instead develop an outlet shopping mall. They retained the hotel and the Grand Ole Opry theater, which now sits across a vast parking lot from a sprawling array of national chain stores and fast food restaurants. Charges that Opryland U.S.A. felt like crass commercialism threatening the Opry’s unique charm in the 1970s now seem quaint compared to the total environment of retail available, and the departed amusement park itself has become the treasured memory in many fans’ minds. Opryland U.S.A. did not ultimately survive, but the Opry itself had accomplished a significant re-branding, a process that did not, however, begin or end with Opryland.

Several months after the move, in the fall of 1974, Opry hostess Carolyn Holloran provided a resonant summation of the Opry’s new home: “It’s true you can take the boy out of the country but you can’t take the country out of the boy, and the same goes for Country music. Country music is wherever the soul of a Country music fan is!” Holloran agreed with leading country figures like Loudermilk, Pride, and Hall that country music fans retained their country identity within themselves (within their very souls), regardless of geography or social class.28

Holloran’s declaration showcased a powerful argument that the inherent character of the music and its people would survive changes in musical production, traditional performance venues, and even the geographic and socioeconomic mobility of its fans. This idea contrasted sharply with a vocal minority of fans who in the 1960s had resisted the Nashville Sound and country music’s drift towards orchestrated urban “pop music.” One passionate fan wrote to the editor of Music City News:

Country Music belongs first to the laboring and rural people of this country. They have no musical training and often can’t even read music, but when the day’s work is done they can take down the old guitar, banjo, or fiddle and play the simple songs that tell about their way of life in a fashion that the finest symphony orchestras in the world can never imitate.

Fans like this one disagreed with Holloran’s sentiment and argued instead that true country music could not be just anywhere a country fan happened to be, but instead had to be rooted in the country and tied to the simplicity and affordances of rural life. By the 1970s, however, these were minority voices.29

As the song lyrics and liner notes suggest, there was widespread ideological support for Holloran’s tautological declaration that country music and country fans could be “wherever the soul of a country music fan is.” Rather than needing to stay in the country (or in older live music venues) to maintain its claim to authenticity, the genre has continually re-worked what authentic country identity could mean in the first place and emphasized traditional values over everything else. Fan club writers praised the Opry’s ability to maintain its unique charm in the sleek new theater, Charley Pride firmly located his rustic roots in the long gone past, and John Loudermilk reminded his readers that country folks’ values trumped just about everything else. These concerns and desires both conditioned the move to Opryland U.S.A. and shaped the contours of the discourse used to defend, rationalize, and in some cases fully embrace the Opry’s new home. For the Grand Ole Opry, the new definition of “country homes” meant declaring that suburban Nashville’s new Opryland U.S.A. entertainment complex was a more appropriate home than the show’s previous host for over three decades, the decaying Ryman Auditorium on the precarious edge of respectability in downtown Nashville. In the early 1970s a wide variety of individuals within the world of the Opry drew on a dominant American discourse which marginalized the urban poor and instead promoted the suburban conservative values of private property, geographic mobility facilitated by socioeconomic resources, and security from the perceived urban threats of crime and immorality. The spatial and rhetorical move played well in terms of branding the Opry and country music as more suburban, middle-class, and family-friendly, but at the expense of a broader, more inclusive, definition of country folks and country homes.

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Jeremy Hill is an independent scholar who received his PhD in American Studies from The George Washington University and his MA in American Studies from California State University, Fullerton. He researches and teaches US cultural, urban, and southern history of the twentieth-century.

Header image: Opry exterior, by Jim McGuire, 1974. Courtesy of the Grand Ole Opry Archives.

NOTES

- As a 1970 article pointed out, “After all, the authenticity and charm of the Opry lies in its unique setting as well as its music.” “History of the Grand Ole Opry House,” Country Music Who’s Who, 1970(Nashville: Record World, 1970), Part 6, 36.

- Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004); Alexander Sebastian Dent, River of Tears: Country Music, Memory, and Modernity in Brazil (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009); Louis M. Kyriakoudes, “The Grand Ole Opry and the Urban South,” Southern Cultures 10, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 67–84.

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “Only the Phony is Real,” New York Times, May 13, 1973, 138; Garrison Keillor, “At the Opry,” New Yorker, May 6, 1974, 46–70; and Paul Hemphill, “Okie From Muskogee,” in The Good Old Boys (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974), 135; for scattered critiques from the margins of country music culture, see also “Interview with the Hagers,” Country Song Roundup, January 1974, 27, and Bill Knowlton, “Cryin’ the Ryman Blues,” Pickin’, May 1974, 10–12, and Doug Tuchman, “Editorial,” Pickin’, August 1974, 2. See Roy Reed, “Grand Ole Opry is Yielding to Change,” New York Times, May 29, 1970, 12, for a less harsh but still pointed summary of the implications of Opryland. “And now, as if to add one more flutter of acceleration to the headlong Americanization of the South, the Opry is getting ready to abandon familiar old Ryman Auditorium in the grit and Victorian decay of downtown Nashville and move to a fancy suburban home that would look as natural in Los Angeles as in the hills of Tennessee.”

- Bill Hance, “Ryman Opened 82 Years Ago With a Prayer, Closes on Amen,” The Nashville Banner, March 16, 1974, 1; Carolyn Holloran, “A Touch of Sadness: Impressions of the Last Night at the Ryman,” Country Song Roundup, September 1974, 32.

- Chamber of Commerce promotional publications emphasized Nashville’s distinction as “Music City, U.S.A.,” pointed visitors towards the Opry House downtown and the Hall of Fame on Music Row, and included a separate listing of “Music City U.S.A. Points of Interest.” Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Publications and Reports, Folder 8 of 11, Nashville Public Library Special Collections.

- Paul Hemphill, The Nashville Sound: Bright Lights and Country Music (New York: Ballantine, 1970), 15–20.

- Stephen Macek, Urban Nightmares: The Media, the Right, and the Moral Panic Over the City(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006). See also Eric Avila’s chapter on science fiction and noir films of the 1940s and 1950s for an early incarnation of this trend, Popular Culture in the Age, 65–105; For a discussion of the neighborhood’s decline and descriptions of its future as a “second-rate retail area,” see John Pugh, “The Future of Lower Broad,” Nashville!, February 1974, 52–62; Chester D. Campbell, “Reshaping A City,” Nashville Magazine, April 1967, 39; Rhodes Johnston, “Downtown Renewal Tops Final Hurdles,” The Nashbille Tennessean, July 26, 1968, 1; on the explosion of suburban shopping centers in the region, see Kathy Sawyer, “Rich Nashville Area Offers Strong Lure for Retailers,” The Nashville Tennessean, June 2, 1968, C-1; Central Loop General Neighborhood Renewal Plan, Project No. TENN R-48 (GN): Economic Re-Use Analysis, Summary of Findings. Prepared for Clarke and Rapuano, September 1963, 26.

- “Interview with Irving Waugh,” Radio and Records, January 27, 1978. See also “WSM Studies Future ‘Opryland’ Complex,” Music City News, November 1968, 21; and Everett Corbin, “Waugh Divulges New Grand Ole Opry Site as WSM Fest Gets Underway,” Music City News, November 1969, 2; and LaWayne Satterfield, “Opryland U.S.A. Gets Go-Ahead,” Music City News, October 1969, 11.

- Roy Acuff, “Introduction,” in Jack Hurst, Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1975), 12; Jack Hurst, Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry, 335; In 1967, just one year before the decision to relocate the Opry, both Coney Island’s Steeplechase Park and Chicago’s Riverview Park had closed their gates after decades of providing urban amusement to working and middle class whites. In both cases, declining attendance numbers were tied to integration and the unwillingness on the part of white families to share such spaces with African Americans. See Eric Avila, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 1–4. Avila uses the fact of these closings to introduce his argument that Disneyland’s location in the suburbs was tied to a shift in the desirability of public space in urban areas along with a new kind of suburban commercial amusement structured around inaccessibility not accessibility. By 1968, Nashville’s civil rights activists had integrated many public leisure spaces, and Music Row had in fact been a site of prominent civil rights protests. See Don H. Doyle, Nashville Since the 1920s (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1985), 252–5. For descriptions of the violence perpetrated by white onlookers against African American picketers of an HG Hills Grocery Store at 16th and Grand (in the heart of Music Row) in the summer of 1961, see Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee Papers, 1959–1972, Reel 40, in the Civil Rights Collection of the Nashville Room, Nashville Public Library.

- G. Daniel Brooks, The National Life and Accident Insurance Company News Release, October 13, 1969, 3, courtesy of Brenda Colladay, Grand Ole Opry Museum, Nashville, Tennessee.

- In 1970, 4,877 white persons lived in the park’s census tract while two African-American persons lived there (Davidson County, home to both suburban Opryland and the downtown Ryman, was 20% black in 1970). The percentage of owner-occupied units near Opryland was 84% and the median asking home price was $21,300, ahead of the countywide median of 18,100 but not even in the top 10 census tracts county-wide in that category. Mostly home to families, two thirds of families in the tract had incomes at least three times the poverty level and only 4.8 percent lived below the poverty line. Nearly 40 percent of the population was under 18, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970 Census of Population and Housing: Census Tracts: Nashville-Davidson, Tenn. SMSA(Washington, D.C.: 1972), P-4, P-12, P-20, P-28; Caleb Pirtle III, The Grandest Day: A Journey Through Opryland, U.S.A., the Home of American Music (Nashville: Opryland, U.S.A., 1979), 23–4; “Opryland U.S.A. Sets America to Music in a 110-Acre Entertainment Park,” Opryland U.S.A. news release, May 1972, Opryland Vertical File, Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville, Tennessee.

- Hance, “Ryman Opened 82 Years Ago,” 1; Historian Alison Isenberg has shown that one of the principal concerns for downtown retailers, as early as the 1950s, was encroachment by the “ring of blight” which was generally thought to surround most American city centers and which was almost always referred to as the “slums.” Business and government officials were worried that what they deemed less desirable commercial establishments would emerge downtown because of its proximity to these residential slums. See Isenberg, Downtown America: A History of the Place and the People Who Made It (The University of Chicago Press, 2004), 189.

- “Opry Member Quotes,” courtesy of Brenda Colladay at The Grand Ole Opry Museum, Nashville, Tennessee. The space between the Ryman and Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge was, in fact, an alley, but one that was heavily trafficked on Opry nights. Wagoner’s suggestion that they only encountered fans in a “dark alley” suggested a more desolate urban space than the one Oprygoers actually experienced. See also Hank Snow’s WSM testimonial: “There is naturally a certain amount of sentiment attached to the old building, but the change will be good. The old Opry house is in a slum area, the parking is bad, and it’s not a safe or fireproof building.”; Hank Snow, interviewed by Douglas Green, September 22, 1975, Country Music Foundation Oral History Collection (Country Music Foundation Library and Media Center), Nashville, Tennessee.

- Gerry Wood, “King of the Hillbilly Singers,” Nashville!, October 1974, 69. For other examples of Acuff referencing drinking and prostitution as the prime reasons to relocate the Opry from downtown, see Roy Acuff with William Neely, Roy Acuff ’s Nashville: The Life and Good Times of Country Music (New York: Putnam, 1983), 197; and Roy Acuff, “Introduction,” in Jack Hurst, Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1975), 12, and Doug Green, “Roy Acuff,” Country Music World, January 1973, 17. City directories indicate that most of these establishments cropped up after the land for Opryland had already been purchased and plans to move set in motion, though the properties changed hands mostly between 1966 and 1968. Acuff himself sold his museum on Lower Broad (for $110,000; he had bought it in 1964 for $30,000)—two years after the move—to an owner who converted it into an adult movie theater, Historic Nashville, Inc., “Downtown Survey,” Nashville Public Library Special Collections, Box 8, Property # 188. Bill Malone, Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002); A fact sheet distributed by National Life “for use by Opry talent in answering questions during personal appearances” emphasized that “pews were chosen for seating because that is the seating in the old House and because they allow families to sit together in close contact.” “Facts Sheet on New Grand Ole Opry House,” courtesy of Brenda Colladay at The Grand Ole Opry Museum. On the importance of the new park being “family-oriented,” see also, G. Daniel Brooks, The National Life and Accident Insurance Company News Release, October 13, 1969, 2.

- Richard Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity (The University of Chicago Press, 1997); Diane Pecknold, The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007). In a memorandum dated March 12, 1973, Ray Canady advised, “Very little time should be devoted to explaining or excusing the Ryman. We must get away from discussing buildings and spend more time on the Opry itself. We need to look ahead, not backwards.” “Move Into New Grand Ole Opry House,” memorandum courtesy of Brenda Colladay, The Grand Ole Opry Museum; for references to Ryman Auditorium as the “mother church” and “ancient holy temple” of country music, respectively, see Paul Dickson, “Singing to Silent America,” The Nation, February 23, 1970, 213, and John Egerton, The Americanization of Dixie: The Southernization of America (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), 207.

- Hance, “Ryman Opened 82 Years,” 1.

- “Opry Member Quotes.”

- Jim Cooper, “Minnie says Howdy to New Ole Opry: Spirit of Tex and Others Present,” Tex Ritter Official Fan Club, June 1974, Country Music Hall of Fame Library Fan Newsletter Archive.

- Kay Johnson and Loretta Loudilla, “President’s Letter,” Loretta Lynn International Fan Club (Wild Horse, CO), March 1974, 4, Country Music Hall of Fame Fan Newsletter Archive.

- Del Wood, interview by Patricia Hall, March 4, 1976, Country Music Foundation Oral History Collection (County Music Foundation Library and Media Center). Similar in spirit, Joseph Sweat’s 1966 article in Billboard suggested that part of the Opry’s appeal was actually “standing in a long ticket line, sitting on hard church pews, enduring another summer night in air-conditionless Ryman Auditiorium.” Sweat made this provocative claim despite the fact that polls of Opry visitors continually showed that the uncomfortable seats and lack of air-conditioning were seen as the main drawback of the Opry. Joseph Sweat, “Keep ‘Opry’ Out of the Space Age,” Billboard’s The World of Country Music, 1966–7 (Cincinnati, OH: Billboard Publications, 1966), 80.

- “Opry Member Quotes.” For a ringing endorsement of the new facilities, see also “Music City Hotline,” Music City News, May 1974, 6.

- In an oral history conducted in May 1974, country star and Opry announcer Grant Turner mildly lamented the Opry’s move and suggested that much of the important colorful character of the Opry came from its wilder, more unpredictable surroundings. Turner mentioned street performers, peddlers, transients (eating chicken from shoeboxes on the steps of the downtown buildings), and even the massage parlors and prostitutes. Turner indicated the Opry’s loss of the surrounding mixed-class character and the various pleasures that it offered, but not publicly; the true feelings or beliefs of many of the Opry stars and fans are hard to know but the public face of the Opry was more unified. Grant Turner, interviewed by Douglas Green, May 13, 1974, Country Music Foundation Oral History Collection (Country Music Foundation Library and Media Center), Nashville, Tennessee.

- John Loudermilk, “Country People ARE a Different Breed . . .” Suburban Attitudes in Country Verse, RCA Victor LSP 3807, 1967. Loudermilk also included specific details (I-65, exit 19), which indicated that he was in fact discussing his own home in the Nashville suburbs.

- Loudermilk, “Country People ARE a Different Breed . . .”

- Charley Pride, “Wonder Could I Live There Anymore,” From Me to You, RCA Victor LSP 4468, 1971.

- Tom T. Hall, “Country Is,” Country Is, Mercury SRM–1–1009, 1974.

- In 1982, American General bought out National Life and Accident Insurance Company. They bought the insurance company but did not want any of the Opry properties and sold the whole Opry package to Gaylord Entertainment, an Oklahoma-based mall and theme park developer. Craig Havighurst, Air Castle of the South: WSM and the Making of Music City (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 237–240.

- Carolyn Holloran, “A Touch of Sadness: Impressions of the Last Night at the Ryman,” Country Song Roundup, September 1974, 32.

- James Kennison, “Letter,” Music City News, October 1965, 2.