"So serious about her orange business, she even created her own crate labels, advertising: ‘ORANGES FROM HARRIET BEECHER STOWE—MANDARIN, FLA.’”

In the years following the Civil War, famed author and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe painted a number of canvases of Florida oranges. One in particular resembles the view from Stowe’s window, displaying a cluster of fruit cascading down a leafy tree. Stowe completed this painting after 1867, when she purchased an orange grove in Mandarin, Florida—a move southward that might have seemed a curious decision for an ardent abolitionist. But purchasing southern land and transforming former plantations into smaller cotton farms and orange groves was considered at the time a charitable act to revitalize the devastated region and transform its political climate. Florida, in particular, was in need of revitalization; the state was dismissed as a primitive swamp and cultural wasteland made worse by the Civil War. Many northerners, Stowe included, believed an orange industry would inspire a cultural awakening in Florida and foster a more egalitarian atmosphere that would supplant industries tarnished by slave systems. For Stowe, the orange represented the promise of a “New South,” and her artistic activism demonstrates how an object as familiar and innocuous as a canvas of oranges held broader implications for Reconstruction in Florida.

Few scholars have investigated Stowe’s overlooked painting practice because it has naturally been eclipsed by her more prominent career as a novelist and abolitionist. Stowe published the celebrated anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852. It became the bestselling novel of the nineteenth century (and the second bestselling book of the century, behind only the Bible) and brought her world-renown as an author and ambassador for the American abolitionist movement. The novel was published in a contentious moment when debates about slavery were intensifying, and it is credited with helping to fuel both the abolitionist movement and the later push to Civil War. At war’s end, Stowe joined several northerners who migrated southward and praised her peers for “applying the habits . . . and industries of New England to . . . the Floridian soil.” In her weekly column in The Christian Union, Stowe encouraged her readers to move south, too, pleading, “To all who want warmth, repose, ease, freedom from care . . . come! Come! Come sit in our veranda! This fine land is now in the market so cheap that the opportunity for investment should not be neglected.” Readers may have been particularly compelled to move south after learning that Stowe yielded a profit of $1,500 a year from her Florida grove.1

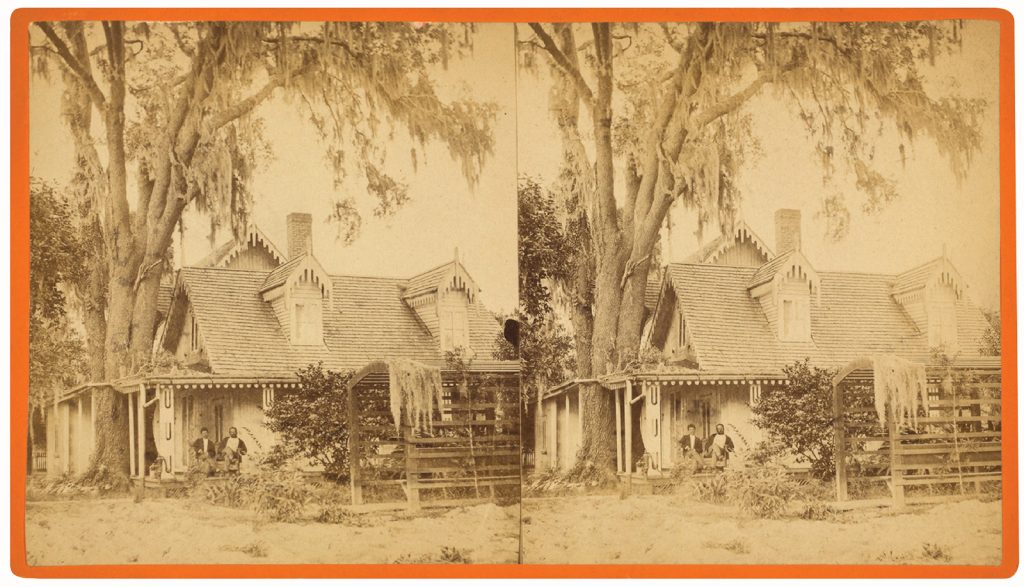

Stowe wrote often of her idyllic orange grove, painting an attractive portrait of Florida as the “Mediterranean of the South.” A photograph shows charming woodwork on the windows and porch of her cottage. It also displays towering trees in her front yard that provided critical shade from the Florida sun. On the horizon line across from the porch, Stowe had a generous view of the St. Johns River. The extraordinary circumstances of Stowe purchasing an orange grove in Florida cannot be overstated. It was highly unusual for a woman to buy land in the late nineteenth century, not least an orange grove spanning 30 acres, but Stowe had her earnings from her book and was able to capitalize on the Homestead Acts, which empowered women, former slaves, and anyone deemed loyal to the Union to cheaply purchase land in the South after the Civil War. Keenly aware that northern migration could bring northern money and influence to the South, Stowe crusaded for Florida oranges in several of her articles and through her artwork. One of her largest paintings, Orange Fruit and Blossoms, is her most unusual. Instead of painting fruit on a horizontal axis as is typical of still lifes, Stowe turned the canvas on its head to show the fruit descending down a long bough. White blossoms dangle from branches like jewelry—a fitting metaphor since Stowe described the period in which orange blossoms begin to bud as “the week of pearls.” She described the process in February of 1880, writing to a friend, “My part this winter has been painting orange trees as they look in our back lot loaded with clusters of oranges, green and ripe and with blossoms . . . I have painted them as they look against a blue sky.” The shallow foreground of the painting suggests that Stowe had an intimate view of the scenery, perhaps one provided by the windows in her home. She wrote, “A great orange tree hung with golden balls closes the prospect from my window. The tree is about thirty feet high, and its leaves fairly glisten in the sunshine.” Stowe expressed great pride in the Florida orange and scoffed at citrus fruits in the North, saying they are “pithy, wilted, and sour” and “have not even a suggestion of what those golden balls are that weight down . . . yonder tree.”2

My part this winter has been painting orange trees as they look in our back lot loaded with clusters of oranges, green and ripe and with blossoms.

In many ways, Stowe’s paintings are unremarkable as they fell in line with gender norms of the time period that promoted fruit painting as an appropriate exercise for women. Stowe, too, claimed that fruit painting was a useful exercise for women, believing that both the illustration and cultivation of plants provided good training for women in the rearing of children. In contrast to men who were encouraged to depict the more intellectual genres of art in history and allegorical paintings that required a study of the human figure, women and artists of color were pushed to paint still lifes and other genres that ranked low on the hierarchy of the fine arts. These limitations did not bother Stowe, who saw dignity in painting the most mundane objects—a quality she admired in the Dutch master Rembrandt who “chooses simple and every-day objects, and so arranges light and shadow as to give them a somber richness and mysterious gloom.”3

Painting oranges was not an exercise in polite culture for Stowe, but a strategic device to rehabilitate the South.

But Stowe also deviated from gender norms by purchasing her own orange grove and managing a network of planters and pickers that typically characterized men’s work on the farm. So serious about her orange business, she even created her own crate labels advertising: “ORANGES FROM HARRIET BEECHER STOWE—MANDARIN, FLA.” Stowe’s crate labels and paintings speak to a larger collection of orange imagery that exists on trade-card advertisements, tourist brochures, and souvenir objects that publicized the burgeoning orange industry in Florida.4

Stowe was deeply committed to becoming an artist, writing in a letter that she was “constantly employed, from nine in the morning till after dark at night, in taking lessons of a painting and drawing master.” Stowe’s training was so intense that she allowed herself “only an intermission long enough to swallow a little dinner.” Her efforts resulted in a catalogue of paintings that extended beyond oranges to include lilies, golden rod, and magnolia flowers. Despite her commitment to mastery, Stowe had a sense of humor about her talent, writing in a letter, “I propose my dear grandmamma, to send you by the first opportunity a dish of fruit of my own painting. Pray do not now devour it in anticipation, for I cannot promise that you will not find it sadly tasteless in reality.” Eventually, she felt confident enough to submit some of her Florida paintings to an exhibition in Hartford, Connecticut, where she sat on the advisory board for the Hartford Society of Decorative Arts. Stowe hoped that by painting Florida fruits and flowers, she might also sell these images and raise money for the South, writing, “I am painting a great panel of orange trees blossoms and fruit which I am going to sell for the benefit of our Church here.” It was not only the content of Stowe’s orange paintings that promoted Florida, but its sale as well. Painting oranges was not an exercise in polite culture for Stowe, but a strategic device to rehabilitate the South.5

There was some urgency to invest in Florida in the years after the Civil War as it was one of the poorest states, requiring a staggering eleven years of reconstruction to fully rejoin the Union in 1877. The war devastated Florida agriculture in particular, causing the collapse of cotton and tobacco plantations and damage to farm buildings and agricultural machinery. The poverty of the region contributed to its reputation as a primitive swamp and tangled wilderness, a “full hundred years behind the North in everything.” Many welcomed a new citrus industry in Florida that signaled a departure from the Old South. As one horticulturist explained, “In former times when our people’s whole time and attention was engrossed in cotton and sugar culture, fruit-growing was looked upon rather with contempt . . . but of late years a new era has dawned upon our people, and they have been awakened to the importance and profits of tropical fruit culture.” In this view, the orange precipitated a cultural awakening in Florida, inspiring farmers to realize the potential of their land. Oranges were also valued for their ability to unite farmers and spread wealth evenly, unlike cotton, which was seen as benefitting a small group of elite planters. Some even wondered if the diversification of agriculture in the South could produce a more broadminded, tolerant perspective in the region. In the era of Reconstruction, orange cultivation promised to “awaken” Floridians and bring social progress to the South.6

Stowe’s accomplishments in painting should be considered side by side her pursuits in writing and activism in providing a fuller picture of her values.

An orange industry was particularly promising to newly freed African Americans who comprised nearly half of Florida’s population. Many freedmen sought new occupations after the Civil War, looking to industries like the Florida orange as a promising departure from more traditional crops. Although it is doubtful that orange cultivation provided better conditions than old sectors of labor, a number of northerners encouraged freedmen to participate in the citrus business, believing it could enrich their lives and wallets. Stowe belonged to this school of thought, organizing black schools and churches in Mandarin and creating orange-picking jobs for freedmen on her grove. She described the positive results in a letter:

I have started a large orange plantation and the region around will soon be a continuous orange grove planted by northern settlers and employing colored laborers. Our best hands already are landholders of small farms planting orange trees and on the way to an old age of easy independence. It is cheerful to live in a region where every body’s condition is improving and there is no hopeless want. You ask if I am satisfied with the progress of Christian civilization in the south. I am.

The “progress of Christian civilization,” for Stowe, was reflected in the principles of Reconstruction, and she clearly viewed her orange grove as an extension of, and contributing to, that work. Although black southerners continued to face systemic obstacles, that some of Stowe’s “best hands” had become landowners managing their own small farms suggests that her orange grove improved the conditions for black laborers and provided them with a happier, more autonomous livelihood.7

It is no coincidence, then, that Stowe so enthusiastically painted Florida oranges in this time period. Oranges were meaningful objects that shored up ideas about cultivation, progress, and reconstruction. Like many New England transplants, Stowe believed that the cultivation of oranges would lead to the cultivation of a “less primitive” Florida. That Stowe depicted the orange in paintings—themselves objects of cultivation and refinement—further reinforced the “civilizing” mission of her Florida orange grove. Stowe’s accomplishments in painting should be considered side by side her pursuits in writing and activism in providing a fuller picture of her values. By painting, selling, and writing about the Florida fruits, Stowe used every opportunity on page and canvas to promote both a new industry and a new era of “easy independence” for black Americans. Her life in Mandarin, Florida, demonstrates how seemingly ordinary paintings of fruit were more than refined objects; they were political ones meant to advance Reconstruction after the Civil war.

Shana Klein holds a PhD in Art History from the University of New Mexico, where she completed the dissertation, “The Fruits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post–Civil War American Art and Culture.” This project, now under contract to become a book, probes how the representation and cultivation of food participated in the broader cultivation of American empire. Klein has been awarded several fellowships for her research, including a current one at the German Historical Institute in partnership with Georgetown University.

NOTES

- Harriet Beecher Stowe, “Letter to Mary Estlin,” December 21, 1868. All letters cited in this paper were collected from the Kirkham Papers in the Harriet Beecher Stowe House Archives in Hartford, Connecticut; “Southern Christmas and New Year,” Christian Union 13, no. 3, January 3, 1876, 144. Stowe used this weekly column as a platform to advertise the South in descriptions of the attractive fruit, flowers, people, and social life in Mandarin, Florida; “Personal,” Christian Recorder, December 21, 1882.

- “Palmetto Leaves from Florida, Swamps and Orange-Trees,” Christian Union, March 25, 1872, 316; “Letter to Susan Lee Warner,” February 16, 1880. This was a productive period in painting for Stowe, who went on to write, “I have painted more than usual this winter—That thing comes over me in spells and this winter is one of them. The last thing was a section of an orange bough with a bright red bird sitting very pert and trim upon it enjoying the prospect-They wouldn’t let me put a red bird in my large panel and so I made one on purpose for him.”; “Letter to Oliver Wendell Holmes,” January 1, 1879; “Palmetto Leaves from Florida, No. 2” Christian Union, January 24, 1872, 156.

- See: Harriet Beecher Stowe, “Raking Up the Fire,” House and Home Papers (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1865), 104–5. Originally quoted in Robin Veder’s “Mother-Love for Plant-Children: Sentimental Pastoralism and Nineteenth-Century Parlour Gardening,” Australasian Journal of American Studies 26 (2007): 27; Catherine Ester Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, American Woman’s Home: Or, Principles of Domestic Science (New York: J. B. Ford, 1869): 295. Harriet Beecher Stowe encouraged women to parent fruits and plants like children. Stowe and her sister Catherine Beecher specifically encouraged mothers to cultivate fruits with their daughters, for they viewed it as a great domestic exercise that promotes health, neatness, sharing, and nurturing skills. William Saunders, author of Both Sides of the Grape Question, also invited young women to experiment with fruit cultivation, saying “friends of the vine everywhere, try it. Encourage your little girls to try it . . . Your children . . . will take delight in watching the development of the young plant trained by their young hands. I know it.” These authors contributed to a wide canon of domestic and horticultural manuals that described fruit cultivation as a training ground for young girls to practice motherly love. The likening of growing children to growing fruit is fitting since fruit cultivation was more broadly thought to help raise and cultivate a refined society. Comparisons between fruit and children highlight the social agency that fruit carried in late-nineteenth century America. Catherine Ester Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, American Woman’s Home: Or, Principles of Domestic Science (New York: J. B. Ford, 1869): 294–5; William Saunders, Both Sides of the Grape Question (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott and Co., 1860): 72; The full quote reads: “I always did admire the gorgeous and solemn mysteries of [Rembrandt’s] coloring. Rembrandt is like Hawthorne, he chooses simple and every-day objects, and so arranges light and shadow as to give them a somber richness and mysterious gloom.” It seems only natural that Stowe found artistic inspiration in Dutch art, a culture known for excelling in paintings of fruits and flowers. Stowe might have learned about Rembrandt and Dutch artist from the reproduction of their paintings in books and engravings that circulated North America. Dutch art also existed in the famous collections of Henry Clay Frick, Charles Wilson Peale, and Nicholas Longworth in New York, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati. These collections, in combination with the immigration of artists from northern Europe, fostered an appreciation for art from this region. It is also known that Stowe travelled to Germany and enjoyed the galleries in Dusseldorf and Cologne. In Abbie H. Fairfield, Flowers and Fruit from the Writings of Harriet Beecher Stowe (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1888), 166. For more information on the history of Dutch art in America, consult Nancy T. Minty’s “Great Expectations, the Golden Age Redeems the Gilded Era,” in Going Dutch: The Dutch Presence in America, 1600–2009 (Boston: Brill, 2008).

- John McPhee, Oranges (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967), 96.

- “Letter to Roxana Ward Foote,” January 3, 1828; “Letter to Bucklin Claflin,” March 6, 1882. The full quote reads: “I am painting a great panel of orange trees blossoms and fruit which I am going to sell for the benefit of our Church here—that is about all I have done in that line.” It is likely that she was referring to the Episcopal Church of Our Savior, a church she helped found in 1880 with her husband Calvin Stowe in Mandarin, Florida.

- Semi-Tropical: A Monthly Periodical Devoted to Southern Agriculture, Horticulture, Immigration, Literature, Science, Art and Home Interests 2 (October 1, 1875): 19–20. The Semi-Tropical was a small-scale agricultural journal published in Jacksonville, Florida, and edited by Harrison Reed. This excerpt in Semi-Tropical paraphrased Ledyard Bill in his book A Winter in Florida or Observations on the Soil, Climate and Products of Our Semi-Tropical State with Sketches of the Principal Towns and Cities of Eastern Florida (New York: Wood and Holbrook, 1870), 19–20. The full quote reads: “The South is full a hundred years behind the North in many things; and this is more true when speaking of Florida than of the other southern states. It is a sort of a wild pasture-ground parceled out into great estates, several thousand acres each, under the old Spanish grants. Not a tenth of the land is yet cleared, while the remaining portion is but a tangle of swamp and pine-forest, interspersed with lakes and rivers.” Quotes of this nature were commonplace, describing Florida as a backwards state comprised of swamp and wilderness; Proceedings of the Florida Fruit-Growers’ Association and its Annual Meeting Held in Jacksonville (Jacksonville: Office of the Florida Agriculturist, 1875), 28; Semi-Tropical 2, no. 2 (February 1876): 9–10. This article in the Semi-Tropical also paraphrases Ledyard Bill in his book A Winter in Florida, 9–10. Bill warns southerners that they will need to switch from a plantation system to a broader farming system. He advocates for the diversification of agriculture in the South, carrying with it a broader diversification and inclusivity in the South. The full quote reads: [Cotton] “was profitable to the large planter; and its tendencies were a concentration of wealth and the elevation of the few: whereas a diversified industry among a people not only makes them more independent, but greater enlightenment follows . . . the whole Southern country to-day needs, more than all things else, a broader culture both in the field and in the school. This accomplished together with an entire revolution of her old-time intolerance and exclusiveness, and her road to independence and importance will be found both broad and easy.” This quote reveals how some believed that changes in agriculture could translate to larger social changes in the South.

- Letter to Elizaebth Georgiana Campbell, May 28, 1877.