“Pies and cakes, pies and cakes. If I merely baked cookies, well, that was slumming.”

In the beginning, he acted like a man who hadn’t eaten a home-cooked meal in twenty years. His first wife had been too unhappy to cook and the second one, too angry. He couldn’t get over my cooking. He didn’t cook, but he’d sit in the kitchen and watch me frying up chicken livers or making Lowcountry crab cakes out of a Charleston cookbook or rolling out a pie crust, and his handsome face wore the balmiest, most satisfied look that I’d ever seen on a man. I’d grown up among southern cooks: my maternal grandmother was from Kentucky and my paternal grandmother from North Carolina. They knew their way around the southern kitchen, and I have their recipes to prove it—though I never saw either of them consult a cookbook. My Kentucky grandmother, Elizabeth, made a twelve-egg angel food cake from scratch that was as tender as fluff and always accompanied by cups of boiled vanilla custard, served chilled, that you dipped slices of the cake into. Her mother, my great-grandmother Mary Yeager, had taught her to churn butter, and Granny had much respect for butter. You never spread anything but on your toast or the yeast-risen bran rolls she baked when you visited her. Granny was a superb pie maker. Her signature dessert was a fairytale concoction called Coronation Butterscotch Pie made with caramelized sugar and slathered with turrets of meringue. She loved to tell the story about that pie saving her marriage.

Granny had much respect for butter. You never spread anything but on your toast or the yeast-risen bran rolls she baked when you visited her.

Despite the culinary delights that came out of her kitchen, Granny was a slow and dreamy cook, forgetful, easily distracted, and disorganized. During the Depression, after she and my grandfather lost their house and lived in a rented cracker-box, he located a German girl who, for room and board, helped Granny cook and clean. But Granny never mastered the art of domestic proficiency. Hosting family reunions, my grandfather always employed a cook to help prepare our evening meal and tidy up afterwards. The one who became our patron saint was a soft-spoken, gently efficient African American woman named Maggie. She worked shoulder-to-shoulder with Granny, and at 4 p.m., when they began their dinner preparations, the kitchen was off-limits to us children. Because of Maggie, Granny stayed on task and we ate on time. Many years later, after a disabling stroke, my mother became slow in the kitchen, too, but she did not want to give up cooking. For inspiration, she hung a picture of Maggie above the stove and carried on.

My North Carolina grandmother, Ruth, a jackrabbit in the kitchen, made cakes more than she baked pies. She served a killer skillet cornbread and deep-fried her own hush puppies. Both my grandmothers fried chicken up a storm. In the summer Grandmother Ruth stirred up the sweetest succotash I’ve ever eaten, a toss of garden fresh baby lima beans and Silver Queen corn, the kernels as tiny and white as baby teeth with lots of fresh black pepper and just the right amount of bacon fat. We sprinkled vinegar and sugar on our sliced German Johnson tomatoes, and she made a watermelon rind pickle so luminous and translucent green it could have come from the Emerald City of Oz.

She served a killer skillet cornbread and deep-fried her own hush puppies.

My mother loved to bake pies, and my first cooking lesson, when I was ten or so, was learning how to make a piecrust. The only pie I didn’t try to bake was the Coronation Butterscotch pie. Its history intimidated me, but Mother was a whiz at it. Only after she stopped cooking did I give it a go, much to my sons’ delight, and for all the trouble it is to make, it’s become a holiday staple.

Today, I’m a big fan of The Moosewood Cookbook, Laurie Colwin’s Home Cooking, The Silver Palate, and the many recipes offered by Melissa Clark and Mark Bittman that I’ve clipped from the New York Times. But my most cherished recipe book, the one I’d grab first if my kitchen caught on fire, is my tattered copy of Marion Flexner’s 1949 Out of Kentucky Kitchens. The plain dusty color of a russet potato, it belonged to my mother. Before I read the preface by Duncan Hines, I thought Duncan Hines was only a brand of cake mix. He was a traveling salesman from Bowling Green, Kentucky, who accidentally became a restaurant critic. He and his wife put together a popular book about his gastronomical pit stops while on the road, called Adventures in Good Eating. Later, he wrote a syndicated column about eateries he’d visited nationwide. “I’m not a professional cook myself, but I do know good cooking . . . All good cooks give to each dish the loving care that it needs,” he writes in the preface.

I happen to believe that you can taste “loving care” if foods are truly prepared with it, and it pleases me to have corroboration from an expert taster. In my mind, the essence of “loving care” is unrushed, small-batch cooking for people you truly like and want to please. When folks asked Duncan Hines where the best place to eat was, he always replied, “In your own home.”

Bring on the butter, lard, cream, sugar, and cake flour—the more, the merrier.

Out of Kentucky Kitchens is loaded with as much lore as recipes. Many recipes are prefaced by stories of how they came to be. “Oscar Heim Meatloaf” was invented by a Kentucky barber; “Dr. Alice Pickett’s Bishop’s Bread or Buttermilk Coffee Cake” originated from a resourceful housewife whose circuit-riding bishop stopped by her home on a Sunday morning unexpectedly; “The Hundred Dollar Chocolate Cake” was the first one I tried to make when I was a girl. The cake’s name derived from how much the Louisville matron who snagged its recipe from a restaurant chef offered to pay him. For a child attracted to stories and storytelling in the fierce way that I was, Out of Kentucky Kitchens was marvelous reading. Some recipes had entertaining voices, betraying the era’s racial dynamics and perhaps providing period “color” in white southern kitchens, like Mozis Addams’s “Recipee for Cukin Kon-Feel Pees” or the heirloom entry called “Minn-ell Mandeville’s Transparent Pie,” whose origins were a Louisville judge’s cook who claimed to have “no receipt” and to just make what came to her mind in the moment. Some recipes were like history lessons: “General Robert E. Lee Cake” was said to be the general’s favorite. It has a lemon filling and an orange-flavored icing.

That’s the sort of cooking I was drawn to and mostly practiced until I was fifty years old. Bring on the butter, lard, cream, sugar, and cake flour—the more, the merrier.

But back to my man and how he loved to eat what I cooked—and I cooked slow, jackrabbit, and loud. I daydreamed and hummed. Then I hurried. I dropped things, cut myself with a paring knife and hollered, splashed around in the sink, rattling pans, made a mess like Julia Child. The chicken would be sputtering in the skillet, the radio playing, my man would jump off his stool and twirl me around, then I’d flip a drumstick. Years later, I would run across an article somebody had clipped from the Greensboro Daily News back when I was growing up in the late 1960s. It was from a local advice column and was titled, “Why Grow Old Alone? Here’s Your Chance to Learn Men’s Likes in Women.” The following quotes are from the men who were surveyed:

“We like women who are good company, but dislike one who is loud. We love that soft, feminine voice.”

“A loud voice is good for a hog caller, but not for a woman who wants to appeal to men.”

“Give us gentle women who think of us as kings, thus inspiring us to respond with the love and loyalty due a queen.”

In our little love-nest kitchen, my king treated me like I was a queen, though I whooped like a hog caller and danced until the buzzer went off. Then I slid an old-fashioned chocolate cream pie out of the oven or a hot milk cake to be iced with “Carrie Byck’s Double Fudge Frosting” from my Kentucky Kitchens cookbook.

“Pie love you,” my man said. “Cake do without you.”

He really and truly talked like that.

Just about the only southern cooking I wasn’t halfway good at was making biscuits, and now and again my man loved a good southern biscuit.

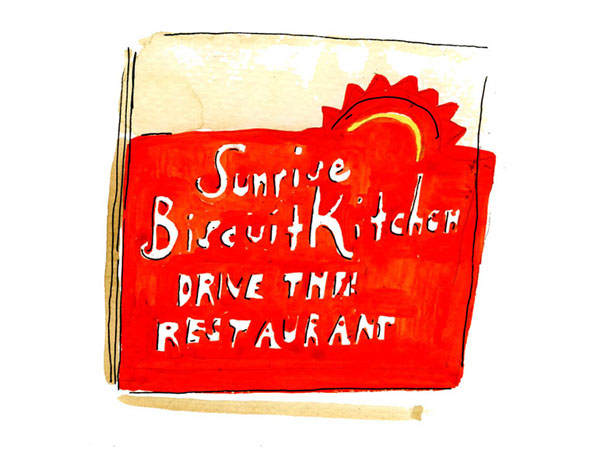

Some days for lunch, we’d cruise down the long east Franklin Street hill to a little hole-in-the-wall drive-thru called Sunrise Biscuit Kitchen and buy chicken sandwiches with pickles, mayo, and mustard. The folks at the Sunrise made a big fluffy biscuit, tender in the center, but with crunch on the top. The chicken was fried. Not as peppery as my grandmothers made theirs, but just as tender, juicy, not overly salted, and crisp. My man sometimes liked his with coleslaw.

‘Pie love you,’ my man said. ‘Cake do without you.’ He really and truly talked like that.

I’d feed him while he drove us somewhere fun, and everywhere was fun back then. Maybe we were just riding over to Home Depot to pick up a box of nails. Fun city. How I loved feeding him that fresh, hot fried chickeny gusto-on-a-biscuit on our way to buy nails. Oh boy, did I love it. I loved the crumbs on his lips, the slash of mustard on his chin I’d wipe off with my pinkie. “Tell me another story about your life,” I’d ask, again and again. All the picayune stuff about him set my brain on fire. “You tell me a story, sugah,” he’d say. I swear to God. Sugah. I loved feeling womanish, but I loved feeling like pudding even more.

Pies and cakes, pies and cakes. If I merely baked cookies, well, that was slumming.

In a few years we’d fattened up a bit. We were middle-aged and our metabolisms had slowed, and I guess we were eating more than we danced. What we couldn’t resist were the desserts I made, night after night, the pièce de résistance after every dinner. Pies and cakes, pies and cakes. If I merely baked cookies, well, that was slumming.

He wanted to lose weight and I did, too. Just a little for me, more for him. He wanted to give up butter and everything that was white: wheat products, sugar, all dairy. For my birthday that year he gave me a cookbook: The Healthy Kitchen, by Andrew Weil, MD, and Rosie Daley, Oprah’s personal chef. Of course I agreed to help. Mea culpa! I had fattened us up to begin with, so encouraged by a man who swooned over every forkful I cooked that I hadn’t paid attention to my culinary terrorism. As previously confessed, I was inclined to fry the hell out of everything.

God! The best livers and onion you ever ate in your life! I made this sugar-and-butter loaded decadence called Katherine Hepburn Brownies, not southern at all, except that I added more of everything—and that’s a southern cook’s tendency. We ate dessert every night we were together, and if I left him with a pan of brownies, he polished them off in half a day. He was a dessert-aholic, he said. No control when it came to sugah. We agreed that we’d gotten fat, but we’d been so happy! Maybe we were happy enough to go on a diet and be OK.

On our diet, many good things happened: we stopped having second and third helpings; I learned to cook with olive oil. I eliminated salting things altogether (you can use lemon instead of salt). We switched to sweet potatoes. We stopped eating beef—he’d read too many disturbing articles about beef processing. No butter. No milk. No bread. We ate soy ice cream if we wanted something sweet. Or tapioca ‘til we choka’d. We used Splenda. Never enda. I think the food I missed most was normal wheat-based pasta. The substitute pasta made with rice and soy was always gummy and tasted gray.

Pounds melted off us like tallow on candles. People noticed. Somebody in my neighborhood asked a good friend of mine if I was sick, maybe doing chemo. After about four months, I went on line and discovered that I was three pounds underweight for my height. I started adding a dessert to my own diet now and again, but he was so pleased with his newly trim self, that he wasn’t about to budge from a successful regimen.

Years later he would still not eat one of my desserts. He seemed to pride himself on the stoicism of refusal. If we gave a party, he sat smiling like the vegan cat who’d refused to eat the canary while guests lapped up my homemade chocolate pound cake with its “sad streak” of fudgy innards or Coronation butterscotch pie, desserts that I associated with our early romance, enticements that he had celebrated and I believed had helped me to bag his affection. Did his rejection of these treats, long after he’d reached his weight loss goal, beget his dismissal of fun as well? Gradually the playful sparkle in his eyes dulled. He had a few professional disappointments and setbacks (don’t we all?), and I couldn’t help thinking that a big old slice of coconut cream pie would have cheered him right out of his doldrums in a way the Styrofoam crunch of rice cakes did not. Certainly I cajoled and tempted him towards the happy foods of our past—offered in moderation. But he said no, as if to drugs. It was going to be all or nothing, and he chose nothing—with ironclad determination. You don’t try to change a sixty-year-old man unless you have experience and past success in moving mountains.

I couldn’t help thinking that a big old slice of coconut cream pie would have cheered him right out of his doldrums in a way the Styrofoam crunch of rice cakes did not.

After we parted, it was a low time for us both. He learned to cook a little and mostly lived off beans. I rented a sunny studio apartment in Chapel Hill, the first space I had ever rented solo. I’d leased a little cottage when I left my marriage, decades ago, but I had children living with me then.

This treehouse, as I call it, in the heart of old Chapel Hill near the Horace Williams house off Rosemary Street, is my first ever home alone. It’s one large room over a tree-shaded three-car garage. It’s only got half a kitchen—a teensy fridge, a two-burner stove top, a toaster oven, a microwave, a couple of drawers and shelves, a Barbie-size dishwasher—but the west windows overlook a glorious rose garden.

On move-in day, the chief carpenter/contractor commandeers the apartment, tending to some last repairs. She’s a sturdy, good-looking young woman wearing jeans and a tool belt. Her employees are both older men. I note her no-nonsense commands of them, the absence of small talk, her omission of the words thank you and please. “Go down to the truck,” she says to one of them. “Find the bag with screws. If it’s not there, go back to Home Depot.”

“I’m actually going to Home Depot after the furniture’s delivered,” I tell her. “Want me to pick up anything for you?”

She sort of snickers. Like, why send a fool shopping when there are men around who will do it and actually know what to buy?

“Where are you going to put the sofa when it comes?” she asks.

“I was thinking maybe …”

“It should go here,” she says, pointing to the space currently occupied by the table and chairs. “That’s the only place it will fit.”

“You think so?”

“I do. Guys, move this table and the chairs to the wall over there.” They do so immediately.

“Thank you so much,” I say as the men skulk off.

“Yep,” she says looking the place over. “We had to change the shelf sizes over the stove. The shelves stuck out over the back burner. The narrower shelves work better. You like to cook?”

“I do.”

“Well, be careful. Don’t burn the place up the first week you’re here.”

After the furniture arrives and the boss lady contractor arranges it to suit herself, I leave to run errands. It’s almost 2 p.m., and I’m suddenly monumentally hungry. Down down down the long Franklin Street hill that runs perpendicular to Estes Drive I roll. Where to get a bite and refuel before shopping? And then, at the bottom of the hill, I spy the sign: SUNRISE BISCUITS and I know without a second’s hesitation that I’ll stop there.

My lungs feel amplified, breathing the biscuity air.

I haven’t eaten at Sunrise Biscuits in probably fifteen years. I didn’t know it still existed. My man and I, on our diets, had years ago nixed Sunrise from our list of eateries not only because of the biscuit factor but the fried chicken breast at the heart of its delicious sandwiches.

The bag the server hands me is warm and aromatic. I’ve ordered our old favorite: chicken biscuit with pickles, mayo, mustard. They load the pickles on—tart coins of perfectly sour green dills. The biscuits are still big and fluffy, scratch-made, golden and crunchy on top. I sneak enough of a nibble to discover that they’ve not changed the recipe. I can’t drive to the nearby park fast enough, where underneath a spindly canopy of wintry limbs, I peel back the paper wrapper, behold, inhale, chomp down. I admire the sunlight sparkling on an oozing pearl of mayo; I turn the sandwich and study its crusty beauty from all angles. There are tears in my eyes as I chew, abandoning myself once again to the sensation of gusto. My lungs feel amplified, breathing the biscuity air. My insides feel petted. I am opening my mouth wider than I have opened it in years to accommodate such behemoth consolation. The chicken tastes as tender as a cloud. Ah, appetite! Let her rip.

Marianne Gingher has published seven books, both fiction and non-fiction. Her work has appeared in many periodicals, including the Southern Review, Oxford American, North American Review, Washington Post Magazine, Veranda, Our State, and the New York Times. She is a Bowman and Gordon Gray Distinguished Term Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she served as Director of the Creative Writing Program from 1997–2002.

Elizabeth Graeber is an artist and illustrator in Washington DC.