Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992.

Texas A&M University Press, 1992.

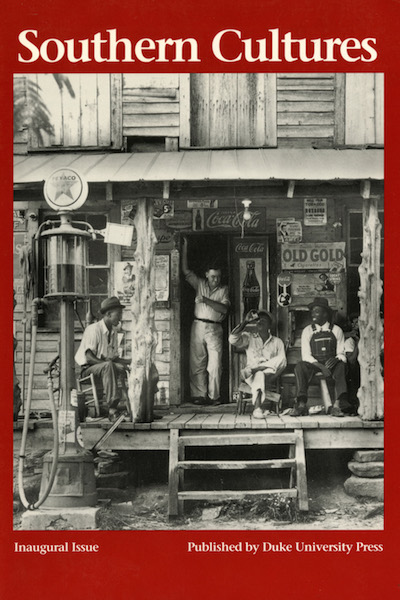

By the late nineteenth century, virtually every Main Street in the United States boasted a photographer’s shingle. No longer did small-town newlyweds, graduates, and decorated veterans have to seek an itinerant cameraman or venture to a metropolis in order to declare themselves in the long gaze of posterity. The democratizing lens made portraiture, once the exclusive indulgence of wealthy patrons, an essential marker in the lives of ordinary individuals, families, and social alliances. Outside the studio—in the workplace, the show room, the sunny street—the camera brought an unprecedented immediacy and persuasiveness to advertising and civic publicity. Owing to inherent strictures of the craft and to centralized sources of equipment, materials, and training, as well as to the inherently modish nature of having a picture taken, these images exhibited a striking, if superficial, uniformity from region to region, and town to town. Decades later, whether preserved and documented in family albums and community archives or displayed anonymously on restaurant walls and in the bins of flea markets, they approximate collective memory.