“[S]uch fiddling and dancing nobody ever before saw in this world. I thought they were the true ‘heaven-borns.’ Black and white, white and Black, all hugemsnug together; happy as lords and ladies, sitting sometimes round in a ring, with a jug of liquor between them . . .” —Davy Crockett (1834)

“There ain’t nothing like a good, solid ride. I don’t care where you are or who you are. It’s just like music—smooth and perfect if you do it right.” —bull rider Alonzo Pettie (1910-2003), “America’s oldest Black cowboy” at the time of his death

“My belt buckle is my bling-bling. It’s just going to keep getting bigger.” —Cowboy Troy (2005)1

Black Hillbillies and Blacknecks

There was no necessary reason why Cowboy Troy’s country-rap single, “I Play Chicken With the Train,” should have caused such an uproar among country music fans when it was released in the spring of 2005. The song itself is a sonic Rorschach test: not so singular a curiosity as many might think, but still a challenge to what passes for common knowledge in the music business. It is animated by a sound and a lyric stance that might strike us, in a receptive mood, as uncanny—at once unfamiliar, a half-and-half blend of two musical idioms that rarely find themselves so jarringly conflated, and strangely familiar, as though the song has distilled the sound of ten-year-old boys filled with limitless bravado, jumping up and down and hollering into the summer afternoon. Compared with other country-rap hybrids, “I Play Chicken With the Train” contains surprisingly few sonic signifiers of hip-hop: no breakbeats, no samples, no drum machines, no scratching. The full burden of audible blackness is carried by Cowboy Troy’s decidedly old-school rap, with its square phrasing, tame syncopations, and echoes of Run-DMC. One hears white voices framing, doubling, responding to, supporting, that Black voice; simultaneously, one senses that somebody has torn down the wall that is supposed to demarcate firmly the boundary between twanging redneck euphoria—the lynch-mob’s fiddle-driven rebel yell—and rap’s exaggerated self-projections of urban Black masculinity.2

The song scans, to receptive ears, as a particularly boisterous example of the male-bonded American pastoral articulated by Leslie Fiedler in Love and Death in the American Novel, a transracial masculine idyll stretching its unencumbered limbs across some country & western frontier, “civilized” men throwing off their generic shackles and reinventing themselves as a fraternity of fearless young warriors out to revitalize the world. Or else—to the unreceptive—it is monstrous, and must be treated as monsters are treated. In The Philosophy of Horror, Noël Carroll defines monsters as entities that are “un-natural relative to a culture’s conceptual scheme of nature. They do not fit the scheme; they violate it. Thus, monsters are not only physically threatening; they are cognitively threatening. They are threats to common knowledge.” The email blast that alerted potential purchasers to the recording’s release fused a kind of King-Kong sensationalism with an assertion of scandalous, unprecedented hybridity: Cowboy Troy, we were informed, is “the world’s only six-foot, five-inch, 250-pound Black cowboy rapper.” Was that a threat, a brag, or a promise?3

In his follow-up album of 2007, Black in the Saddle, Cowboy Troy referenced the antipathy with which some whites and Blacks greeted the song and, by extension, his highly conspicuous presence in the country music world. “People I’ve never met wanna take me body surfing behind a pickup,” he sang in “How Can You Hate Me,” referencing the infamous dragging death of James Byrd Jr. in Jasper, Texas, at the hands of two white men. As for the Black response to his hick-hop persona: the silence from hip-hop precincts, at least publicly, has been deafening, although Vibe magazine did take note of Black in the Saddle long enough to sneer at Coleman’s presumptive audience: “Troy and his twang trust are keen to serve two masters: game exurban Blacks steeped in country grammar and white fans of post-redneck rock. Together, at last.” Coleman’s rejoinder to his Black critics in “How Can You Hate Me”—”some of y’all sayin’ Troy ain’t nothing but a Sambo”—suggests that he has indeed taken some heat.4

Although it received virtually no airplay on country music radio, Loco Motive—the album out of which “I Play Chicken with the Train” was released as the first single—debuted at #2 on Billboard‘s Top Country Albums chart on June 4, 2005. Within weeks, Troy Coleman, a former Foot Locker shoe salesman from Dallas, had the #1 download at iTunes and was a success du scandal in the country music world, along with his producers and backup singers, the alt-Nashville duo of “Big Kenny” Alphin and John Rich. From media reviewers to country music websites such as CMT.com and VelvetRope.com, the nature of Cowboy Troy’s scandal seemed evident to his supporters and detractors alike: he had dared to create hybrid art by mixing two musical idioms understood to be racially pure, country and rap, thrusting his hip-hop braggartry into country’s pristine white precincts with the help of his renegade white producers. “[S]tomping middle ground between the Sugarhill Gang and Charlie Daniels,” opined Time; “a new kind of American music, equal parts metal, country, hip hop, and balls,” wrote another reviewer. Admiration was supplanted by disgust in the postings of those who styled themselves as country music’s defenders. “He has tried to come into country to pollute it with his rap-junk,” wrote one. “He is just polluting this awesome genre,” wrote another. “This is such an abomination,” wrote a third. “A discrace [sic] to humanity . . . Troy on stage and the white girls down front dancing for him.” The racist tenor of the “pollution” claim becomes unmistakable when juxtaposed with the “abomination” of an imagined racemixing in which Black masculine potency looms over compliant white womanhood. (Perhaps it’s worth noting that the original film version of King Kong was retitled King Kong and the White Woman for its German release.)5

The train that Troy was jousting with in his hit single was, as he readily admitted in interviews, the Nashville country music establishment that had, with several notable exceptions, refused to allow Black performers to become stars, much less country/rap stars. By the summer of 2006, Coleman, backed by Big & Rich, had performed his train song at the Grand Ole Opry and had a steady gig co-hosting Nashville Star, a country music version of American Idol, with Wynonna Judd. But the song, as it happens, references two trains: not just the racist-Nashville-establishment train, but the “big black train comin’ around the bend” as a figure for Cowboy Troy himself, an outsized musical revolutionary roaring full tilt into country music’s airbrushed myths of whiteness to “see which one of us is going to flinch first”: “I’m big and black, clickety-clack,” he bragged, “and I make the train jump the track like that.” The self-styled “hick-hopper” and “blackneck” had played chicken with the train, and the train had swerved.6

Recent scholarship by Pam Foster, Charles Wolfe, Louis M. Kyriakoudes, Elijah Wald, and others has significantly undercut these myths of white stars, aesthetics, and audiences—above all the myth of Charley Pride, lone Black superstar, as the exception that proves the rule about the thoroughgoing whiteness of country. We now know that John Lomax collected canonical versions of “Home on the Range” and “Git Along Little Dogies” from a retired Black cow-camp cook; that the founder of the Grand Ole Opry, George Hay, launched his career by penning newspaper and radio blackface skits; that harmonicist DeFord Bailey, the first star of the Opry, was the product of an extensive Black hillbilly tradition that otherwise remained all but unrecorded; that Hank Williams and Bill Monroe need to be paired with their early-career African American partners and mentors, Rufe “Tee Tot” Payne and Arnold Schultz; that the Carter Family learned much of their mountain repertoire from their Black guitar player, Leslie Riddles; that the Supremes and the Pointer Sisters released country-themed albums in 1965 and 1974, respectively; that a number of talented Black country performers have surfaced in subsequent decades, including Cleve Francis, Al Downing, Stoney Edwards, and Trini Triggs; that Merle Haggard, disgusted with contemporary Nashville, insisted in 1994 that “I’m just a little blacker than that” and “I’m thinking of doing some tours through the South only for black people”; and that country music has long had a passionate Black fan base in Africa and the Caribbean and a significant, if little-acknowledged, following among Black southerners, including musicians. Questioned by folklorist Alan Lomax at his home near Clarksdale, Mississippi, in the early 1940s, Muddy Waters proudly listed seven of Gene Autry’s hits in his working repertoire, including “Deep in the Heart of Texas” and “Take Me Back to My Boots and Saddle.” “You have to play all the Western tunes for the colored these days,” insisted another Black Delta musician who played on a cowboy music radio show every Saturday afternoon. The prelude to Ray Charles’s epochal album Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music (1962) was his late-1940s gig with the Florida Playboys, during which he “yodeled, wore white western suits, and . . . was dubbed ‘the only colored singing cowboy.'” “When I played hillbilly songs,” Chuck Berry remembers in his autobiography, speaking of his days at the Cosmopolitan Club in St. Louis, “I stressed my diction so that it was harder and whiter . . . Some of the clubgoers began whispering, ‘Who is that black hillbilly at the Cosmo?'”7

Still, there’s a difference between demonstrating mastery of the country idiom, as Berry, Bailey, Charles, and Pride did, and loudly proclaiming your disruptive role in accents that frame your entrance as Blackness Triumphant. According to one Nashville journalist, Troy Coleman was so aware of his polarizing potential that he “briefly toyed with the idea of sending [Loco Motive] to radio programmers along with a roll of toilet paper and a bottle of Pepto Bismol. ‘I figured [program directors] would need one or the other,’ he says, ‘depending on how excited they got or how sick they felt’ after hearing it.” The only major country station that played him, according to producer John Rich, was KTYS in Dallas, although the album went on to sell more than 340,000 copies. Coleman’s contested Nashville ascendance deepens our understanding of his aggressively provocative train song. The audible racial scandal he seems at first to enact—the flagrant mixing of “his” black rap with “white” country music—is, I suggest, merely a screen for an altogether different scandal: his implicit demand that we understand both musical traditions as already amalgamated. More specifically, “I Play Chicken With the Train” combines frontier brag-talk of the Davy Crockett variety with urban rap braggadocio in a way that forces us to acknowledge the shared, creolized history of both forms, a history that owes something to African praise song, something to blackface minstrelsy, and much to life on the Western frontier before and after Emancipation.8

Cowboy Troy’s hick-hop is a challenge to our received understandings not just of country and rap, but of musical Blackness and whiteness more broadly—a transracial “excluded middle” of a sort explored by Christopher Waterman in a recent article on the song “Corrine Corrina.” “One effective way to analyze the logics of inclusion and exclusion that have informed the production of racialized music histories,” Waterman writes, “is to examine music that springs from, circulates around, and seeps through the interstices between racial categories.” Cowboy Troy’s hick-hop is merely one example of an emergent country-rap tradition that includes artists such as Trace Adkins (“Honky-Tonk Badonkadonk”), Vance Gilbert (“Country Western Rap”), and Insane Shane McKane (“I Put the Ho in Hoedown”). Even considering the liberatory potential of Troy’s transracial aesthetics, the long shadow of blackface minstrelsy lingers within his comic self-enlargements and surfaces in the Big & Rich stage show that frames some of his public performances—a show in which Troy shares the stage with a dancing dwarf named Two-Foot Fred. It’s worth remembering, in this context, that country music as we know it evolves out of “hillbilly” music, whose early performers came from the ranks of vaudeville and medicine shows where “blacking up” was part of the business. Their performances—straight down through the television hit Hee Haw—mingle roughshod comic burlesques and the winking self-mockery of the country rube. “[T]hrough much of its history,” historian James N. Gregory reminds us, “country music courted ridicule and needed audiences who either enjoyed the joke, missed the joke, or did not care.” Although several white artists, including Bubba Sparxxx, have configured country-rap as a medium for serious reflection, Cowboy Troy’s version of the idiom—it’s a scene of playful, wildly self-dramatizing transgression, inflected by Coleman’s acknowledged fondness for the World Wrestling Federation and its stagey braggartry—is seconded by the recordings of Adkins, Gilbert, and McKane. McKane’s double-edged burlesque, in which he mocks Black culture and redneck culture by mocking his own obscene, rhythmically-challenged hip-hop stylings, shows how racist meanings can haunt the “brothers under the skin” aesthetic of the transracial frontier.9

Raps, Recitations, and Postmodern Honky-Tonks

The final words of “I Play Chicken With the Train,” flung down as an invitation and a challenge on the heels of the completed track, are Troy’s: “Get you some of that.” But what exactly is that—apart from the provocative fusion of “white” and “Black” music that feels like sacrilege to some and refreshing innovation to others? Coleman’s own statements, which offer multiple and conflicting evocations of one hick-hopper’s self-fashioning, are a good place to begin this investigation.

In an interview with National Public Radio’s Jennifer Ludden during the first rush of post-release publicity, Coleman insisted that what sounds like rap to some people is, in fact, merely his updating of the “recitation,” an established mode within country music itself. “[Y]ou start listening to old Charlie Daniels records and listening to old Jerry Reed records,” he said, “[and] the delivery a lot of times is considered—it was called recitations at that time, but if you listened to it now, you’d probably call it a rap, but it was mostly spoken and everything rhymed.” Troy’s claim—that he isn’t so much hybridizing country with rap as he is highlighting a preexistent strain within the former idiom—positions him, unexpectedly, as the conservator of country music tradition, even as it implicitly rebukes those country fans who view him as a “polluting” interloper. Later in the same interview, however, Coleman offers a different origin-narrative in response to the question, “[W]here’d you come up with the idea to put all this together?”

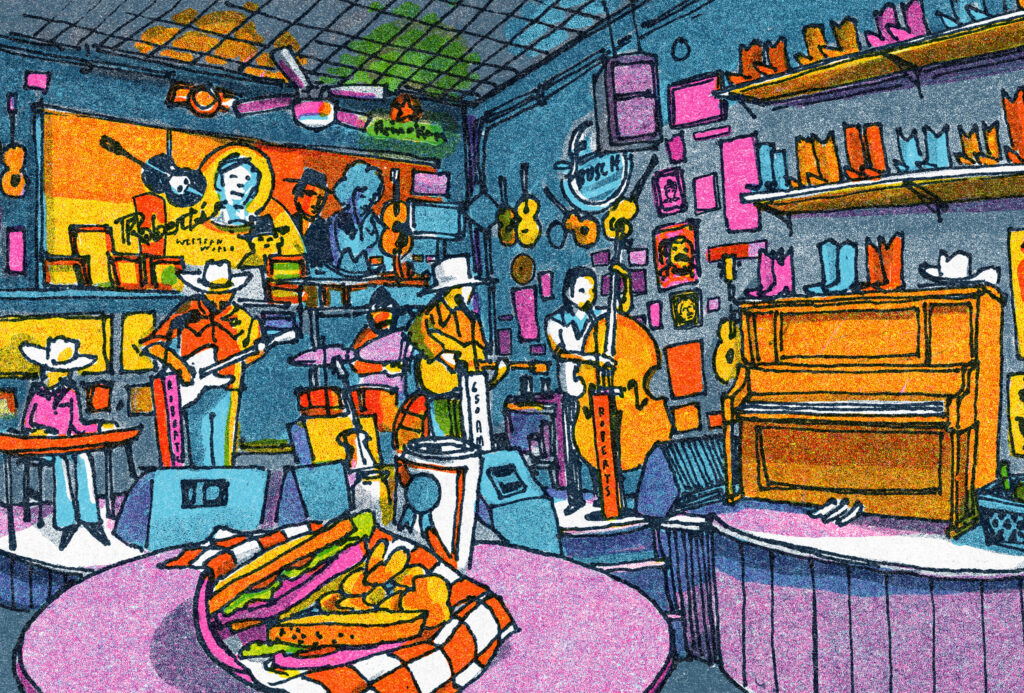

Well, I think that if you have ever spent any time, for example, in country bars in Texas, as I have and many of my friends, you’ll notice that during the first 45 minutes or so of a show, the band or the deejay is playing traditional Top 40 country music. However, during that last quarter of the hour, the deejay begins to play either rap, rock, or, you know some sort of dance music, and the dance floor always gets packed during the rap portion of the hour. And that let me know that I wasn’t the only COWBOY that lik [sic] rap music as well as country music. And so I figured, why not make a style of music that appeals to me as well as to my friends and something that I know that there is a market for?10

“[I]f you’ve been to a country bar recently,” he told Time in a similar vein, “and seen people dance to a George Strait song followed by a Ludacris song, you know I’m hardly the only person that likes rap and country mixed together.” Here Coleman represents himself as an innovator responsive to the needs of an emergent public: the regular crowd in a modern honky-tonk, united in their protean tastes and shaking their denim-clad booties to Dirty-South hip-hop grooves. The contemporary country audience’s tastes clearly resonate with his own—and do so in a way that highlights the potential for profit that lies within stylistic innovation. In “I Play Chicken With the Train,” Coleman brags about his global reach and selling power—”All over the world wide web you’ll see / Download CBT on an mp3″—but what he signals in his public statements is a desire to meet an eager audience halfway by synthesizing a hybrid idiom: “I grew up listening to country music, rap music, and rock ‘n’ roll . . . I figured, ‘Why can’t I take my favorite elements of all three and mix them into one style?'” His objective, he told journalist Farai Chideya in rhyming accents, “is to strive for connection regardless of complexion.”11

The origin of his aesthetic shifts in Coleman’s telling from childhood home to honky-tonk to frat party. As an undergraduate at the University of Texas in Austin, a town celebrated for its musical eclecticism and alt-country temperament, Coleman began performing at frat parties and clubs: “I had my cowboy hat on and would rap over techno,” he told the Sun-Herald. “People started remembering who I was, I guess, because I had the cowboy hat on everywhere I went.” The “big blackneck” persona Coleman dramatizes in his country rap hit seems to have had its origins in this collegiate clubbing life. “I’d go to country bars,” he told a British journalist, “and I’d be one of two or three blacks in the entire place. Then I’d wear a cowboy hat and boots to a hip hop club. People thought I was brave or crazy.”12

“[S]yncretism will always be an unpredictable and surprising process,” insists Paul Gilroy. “It underlines the global reach of popular cultures as well as the complexity of their cross-over dynamics.” The complexity of Coleman’s crossover lies in the tension between the self-evident disruption of his song and cowboy-hatted presence on the one hand, and, on the other, the aesthetic and attitudinal continuities he claims in interviews such as these. Even as “I Play Chicken With the Train” organizes its aggressive braggadocio around the tall, dark, unruly figure of Cowboy Troy whooping on (white) Nashville, Coleman’s own statements insist that there is no scandal. Country folk and rap folk are actually the same folk, he claims, with their transracial affinities reflected not just in the willingness of white honky-tonk dancers to boogie down to hip-hop grooves, but in shared lyrical concerns. In response to Ludden’s comment that “[o]ne doesn’t normally think of a country music audience and a hip-hop audience overlapping,” Coleman responds, “Well, that would be a traditional concept . . . but if you really listen to the lyrics of the songs, I mean, many of the themes that are within the music on either side of the fence are quite similar. I mean, a lot of people that listen to rap music like to talk about the cars that they drive or the trucks that they drive. And similarly, in country music, they like to talk about what they drive as well.” Coleman continues, “A lot of rap is about drinking and having a good time. Country artists sing about that stuff too.” Coleman is not the only Black rap artist to have ventured a claim about the thematic continuities between country and rap. In a review of Loco Motive entitled “Is Nothing Sacred? Country Meets Hip-Hop,” journalist Ernest Jasmine reports a conversation he had with Ice-T in which the topic unexpectedly turned towards similarities between rap and country artists. “They are both down to earth and wore jeans and hats to awards shows, [Ice-T] pointed out. He even alluded to hip-hop gangsta, quoting Johnny Cash: ‘I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.’ When I joked that he should record a country album, he cut me off, saying something like ‘We have different agendas.'”13

As Ice-T’s bridling response suggests, Black rappers have been as quick to discern stylistic affinities with the western half of the country & western dyad—especially hypermasculine frontier mythology involving posses, big guns, and outlaw behavior—as they have been leery of country music per se. In an essay titled “Hip Hopalong Cassidy: Cowboys and Rappers,” Blake Allmendinger mentions a series of relevant rap recordings and films, including “Ghetto Cowboy” (Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, 1998), “Westward Ho” (Ice Cube/Westside Connection, 1996), “California Love” (Tupac Shakur, 1995), Posse (Mario Van Peebles et. al., 1993), and The Wild Wild West (1999), the last of which features Will Smith as “the cowboy who outdraws the outlaws, the rapper J. W. G. (‘James West Gangsta’), who outrhymes his competitors.” Snoop Dogg dedicated his 2008 novelty hit “My Medicine,” a southern-fried paean to pimping and pot-smoking, to “my main man Johnny Cash, a real American gangster.”14 Yet even as Cowboy Troy dramatizes his emergence onto a Western stage in “I Play Chicken With the Train” with a bravura not unlike Smith’s, he rejects the gangsta pose with its emphasis on violence, on being “hard”:

Southern boy makin’ noise where the buffalo roam

Flesh, denim and bone as you might have known

See me ridin’ into town like a desperado

With a big belt buckle, the cowboy bravadoRollin’ like thunder on the scene

It’s kinda hard to describe if you know what I mean

I never claimed to be the hardest of the roughest hard rocks

But I’m boomin’ out yo’ box

Skills got you jumpin’ outch’a socks

What distinguishes Coleman’s frontier mythology from those of other Black rappers is the public for whom he conjures Cowboy Troy: not an inner-city Black audience looking to an imagined West for outlaw poses and high-octane gun fetishism, even as it views country music as the soundtrack of rural racism; not a mainstream American audience happy to indulge Will Smith’s benign gangsta stagings; but a contemporary country music audience sufficiently heterogeneous that those who take offense at the “pollution” of Coleman’s rap are counterbalanced by those happy to dance to Ludacris and George Strait at their local honky-tonk. “Country music today,” wrote sociologist George H. Lewis in 1997, “is not the music of a relatively homogeneous blue collar subculture, as it was, purportedly, in the past” and instead “has revealed several distinct demographic clusters of country fans . . . .” Lewis identifies the expected “hard-core traditionalists” and “transition-30 baby boom listeners,” both of which are attracted to country in part because it aligns with conservative community and family values, but he also identifies a younger “Lollapalooza-age” audience—an alt-country audience, broadly speaking—that embraces everything from Killbilly to the Dixie Chicks. Finally, there are “country converts” who, according to Lewis, “consume the music as part of their extremely varied musical listening pattern. These musical omnivores . . . are the complete postmodern grazers—equally likely to purchase and enjoy the work of Cecilia Bartoli, Phish, and Merle Haggard—and are, by the way, the fastest growing segment of the modern country listening audience, clocking in at nearly 30% of it in 1996.” Cowboy Troy’s core appeal would seem to lie with the third and fourth demographic clusters, younger alt-country fans and eclectic “grazers.” Coleman’s own edgy, wide-ranging tastes fit this demographic. The list titled “To My Heroes” at CowboyTroy.com includes Charlie Daniels (“You really struck a nerve with me early on and got me into country music with an edge”), Jerry Reed, Dwight Yoakam, Tim McGraw, Metallica, Bruce Willis, Will Smith, Denzel Washington, Gretchen Wilson, Run-DMC, and Clint Eastwood.15

What sets Coleman apart, again, is the way in which he counterpoises a sincere musical eclecticism with a provocateur’s instinct to foreground his bigness and Blackness in a way guaranteed to inflame country traditionalists. His producers, “Big” Kenny Alpin and John Rich, never fail to invoke Coleman’s height and race in their public statements, even as they emphasize their antiracist bona fides. The hip hop-tinged name of their production group, Muzik Mafia, stands for “Musically Artistic Friends in Alliance”; their corporate creed, taking direct aim at a Nashville establishment and fan base presumed to be racially retrograde, is “Country music without prejudice”; and their record label, Raybaw Records, is an acronym for Red and yellow, black and white. It might be argued that what Big and Rich are offering here, with Cowboy Troy’s help, is a corporatized version of racial reconciliation in which all one need do is sing, sing, sing—and buy, buy, buy. But there is also evidence that the singing and buying, along with the temporary community created during live performance, has had a transformative effect on country fan culture. “How many black people show up at your shows?” Chideya pressed Coleman during her 2007 interview. “I have noticed that over the last couple of years,” he responded, “there has been a darkening of the audience at our country shows. And I think that that has gotten to the point where . . . people are saying that they are starting to feel more comfortable coming to the shows because, obviously, there has been some, sort of, stereotype about country audiences and it’s, you know, semi-unfair.”16

“I Play Chicken With the Train” limns the paradox that is Cowboy Troy: a spectacularly self-foregrounding Black subject who wants to summon us into an expansive country & western clearing where we dance out whatever it is that divides us—the racially restrictive “train” symbolized by Nashville, above all—and rejoin the world transformed:

People said it’s impossible,

Not probable, too radical

But I already been on the CMAs

Hell, Tim McGraw said he liked the change

And he likes the way my hick-hop sounds

And the way the crowd screams when I stomp the ground

I’m big and black, clickety-clack

And I make the train jump the track like that

There is indeed a paradox at work here, but it’s not precisely the paradox I’ve outlined above. If Cowboy Troy makes the train jump the track and ends up hosting Nashville Star, it is because his brag-talk, the heart of his game, is neither Black nor white, but both: Dallas-born rapper as a latter-day gamecock of the West, and deeply in the American grain.

Frontier Breakdowns and Transracial Brag-Talk

The most productive way of illuminating the “that” served up by “I Play Chicken With the Train” is to focus on the unabashedly self-inflating voice that dominates the song: not just Troy’s rap but also, crucially, the twangy titular refrain sung by Big & Rich that frames and responds to it. To paraphrase the title of a story by Eudora Welty, Where does this voice come from? Out of which cultural wellsprings does it emerge? Some of those wellsprings are indisputably African American. Literature scholar Fahamisha Patricia Brown speaks of “the self-affirming voice” in African American poetry, with its “annunciatory ‘I am,'” as having “strong vernacular roots in the boast, a genre of poetry from urban street culture in which young men, in the most hyperbolic manner, affirm their worth in terms of physical strength, sexual prowess, and the ability to inflict harm.”17

Those hard-core traditionalists who deride Cowboy Troy’s brags as “rap-junk” polluting the presumptively white precincts of country music have common cause on this point with Brown: both would demand that we hear Coleman’s—and Nelly’s, and Ludacris’s, and Run-DMC’s—self-aggrandizing style as a powerful evocation of Blackness. As Waterman notes, “[M]usic [in the United States] has long played a privileged role in the naturalization of racial categories . . . . In musico-historical discourses, the retrospective construction of well-bounded, organically unified race traditions—musicological corollary of the infamous onedrop rule—has tended to confine the complexities and contradictions of people’s lived experience . . . within the bounds of contemporary ideological categories.” “Black music” is one such ideological category, and over the past twenty-five years the most immediately recognizable sign of musical Blackness, regardless of how many white kids flock to the music, has been the rapped brag. When Black Brooklynite Radio Raheem thumps his boom-box down on the counter of Sal’s Pizzeria in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989), the declamatory tones of Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” irritate and accuse the white pizzeria owner to precisely the degree that they exhilarate and empower Raheem; the audible Blackness of Black music is being wielded like a club—and by whites and Blacks simultaneously, facing each other across an unbridgeable racial divide that the music both incites and reflects. Hard-core white traditionalists who sneer at Cowboy Troy’s “pollution” of country music and the far better-known cohort of contemporary African American rappers who glory in their own vocalized hustle and flow are recapitulating Sal and Raheem: polarized in every other respect, they’re united in the view that rap is Black. But is it?18

If one wanted to retrospectively construct a “well-bounded, organically unified race tradition” behind Coleman’s outsized performance, one could indeed sketch a plausible genealogy. The line of descent responsible for the “urban contemporary vernacular language situation of ‘rappin,'” as Brown calls it, leads us back through southern-born boasters and toast-makers like H. Rap Brown, Shine, and Dolemite (Rudy Ray Moore) and into the arms of blues boasters like Bo Diddley (“I walked 47 miles of barbed wire / I used a cobra snake for a necktie”) and Willie “Hoochie Coochie Man” Dixon. The blues boaster, according to folklorist Mimi Clar Melnick, “dreams of personal greatness, . . . brags of his accomplishments, and in no uncertain terms establishes himself as a hero . . . There is also a strong identification with objects of power and speed—trains, weapons, cars, even large cities—which sometimes perform the boaster’s feats for him or which lend him, through his intimacy with them, the attributes of a kind of superman.” The Black blues boaster in turn takes cultural energy from earlier Black badmen such as Railroad Bill, Stagolee, Aaron Harris, and Two-Gun Charlie Pierce, all of whom achieved iconhood in a series of turn-of-the-century ballads in which an admiring Black community—rather than the badmen themselves—brag of their exploits, often against symbolic representatives of a larger (white) world understood to be oppressive: “Railroad Bill he was a mighty mean man / He shot the midnight lantern out the brakeman’s hand / I’m going to ride old Railroad Bill . . . / Buy me a pistol just as long as my arm, / Kill everybody ever done me harm, / I’m going to ride old Railroad Bill.” The braggart here, to repeat, isn’t the badman himself but the singer who has been inspired by his exploits. Still, the line of descent from “Railroad Bill” to “I Play Chicken With the Train” is readily discernable.19

As we venture back into the period of antebellum slavery, the trail grows more faint. Cultural historian Lawrence Levine and others tell us that the cocky, boastful, self-affirming Black voice was not common on the plantation, and not simply because such self-foregrounding would have incited severe reprisal from the master. Secular slave heroes, according to Levine, “operated by eroding and nullifying the powers of the strong; by reducing the powerful to their own level,” and it was only with emancipation that African Americans fashioned

their own equivalents of the Gargantuan figures that strode through nineteenth-century American folklore. Indeed, the presence of such figures in Black folklore [i.e., badmen] was, along with the decline of an all-encompassing religiosity and the rise of the blues, another major sign of cultural change among the freedmen.20

Leaving aside those Gargantuan figures for a moment, it seems clear that Levine’s several claims problematize any argument for the exclusively African American origins of rap braggadocio. Brown herself skirts both the antebellum plantation and minstrelsy, preferring to deep-source rap’s tall-talk, with some scholarly justification, in the African praise-song tradition. A tradition of self-foregrounding praise-songs or ijala has long flourished among Yoruba hunters. “I am physically sound and in great form,” declaims one such hunter at a thanksgiving feast. “I will speak on, my mouth shall tell wondrous things.” In the Mandingo epic, Sundiata, drawing on the warrior side of this tradition, contending princes exchange lines such as “I am the poisonous mushroom that makes the fearless vomit” and “I am the ravenous cock, the poison does not matter to me.” According to Brown, such songs of self-praise persisted in African American culture, presumably enduring a forced latency period on the plantation before flowering after Emancipation as stylized braggartry or “self-introductions” in the various forms described above. Cowboy Troy’s claim that he’s “big and black, clickety-clack, and [makes] the train jump the track,” in other words, is deep and multiply sourced in the African American cultural past.21

The problem with this genealogy isn’t that it’s wrong, it’s that it’s incomplete. It constructs a “well-bounded, organically unified race tradition” by leaving out the other great American tradition of “self-affirming voices” with their “annunciatory ‘I am'”s from which Cowboy Troy, and rap as a whole, also draw their inspiration: Davy Crockett, Mike Fink, and the ring-tailed roarers of the old Southwestern frontier. In 1831, James Kirke Paulding fictionalized Davy Crockett as the frontiersman Nimrod Wildfire in his play, The Lion of the West, and voiced his larger-than-life persona with memorable concision: “I’m half horse, half alligator, a touch of the airthquake, with a sprinkling of the steamboat.” This mode of exaggerated self-presentation was intimately linked, as historian Elliott Gorn and literary scholar Christian K. Messenger have shown, with the evolving practice of rough-and-tumble fighting in the backcountry and the “temporary play communities” such practices established. “By the early nineteenth century,” according to Gorn, “simple epithets evolved into verbal duels . . . Backcountry men took turns bragging about their prowess, possessions, and accomplishments, spurring each other on to new heights of self-magnification . . . . [A frequent] claim [is] that one was sired by wild animals, kin to natural disasters, and tougher than steam engines.” The so-called raftman’s episode in Twain’s Life on the Mississippi (1883) features two backwoods brawlers who trade threatening self-introductions with as much gusto as any pair of posturing African warriors: “I’m the man they call Sudden Death and General Desolation,” announces the first. “I take nineteen alligators and a bar’l of whiskey for breakfast when I’m in robust health,” answers the second, “and a bushel of rattlesnakes and a dead body when I’m ailing!”22

Although we might be tempted to code such frontier bluster as “white,” if only in an attempt to establish it as parallel to, and distinct from, the African American tradition just outlined, the truth is that both cultural streams have long intermingled. After trading threats and insults, we might remember, Twain’s raftsmen and their crew “[get] out an old fiddle, and one played and another patted juba, and the rest turned themselves loose on a regular old-fashioned keel-boat breakdown.” African American cultural materials—the juba rhythms, but also the plantation-inflected fiddling tradition and the breakdown itself, named after a popular plantation dance—are essential constituents of cross-racial exchange on the frontier. “The backwoodsman and the Negro danced the same jigs and reels,” maintained cultural historian Constance Rourke; “the breakdown was an invention which each might have claimed.” Davy Crockett himself was a proficient fiddler and blackface performer; “[H]e should . . . go down in history,” argues Leon Wynter, author of American Skin: Big Business, Pop Culture, and the End of White America, “as the first American pop star to sport a bit of ‘white Negro’ persona.”23

Whatever contributions African Americans may have made to this transracial country West, this brag-talking breakdown-driven culture of the frontier, prior to Emancipation, Levine and others agree that freed slaves and their children and grandchildren embraced that culture and the rhetoric of self-aggrandizement and self-assertion it enabled in various ways, including the so-called badman persona. “I’se Wild Nigger Bill / Frum Redpepper Hill,” sings one “Negro youth” sitting near the railroad tracks with a banjo on his knee, in a post-Reconstruction tale related by folklorist H. C. Brearley. “I never did wo’k, an’ I never will. / I’se done kill de boss; / I’se knocked down de hoss: / I eats up raw goose widout apple sauce!” Even H. Rap Brown, self-styled as “sweet peeter jeeter the woman beater,” drew on the language of the frontier in his signature rap, calling himself “[t]he deerslayer the buckbinder . . . Known from the Gold Coast to the rocky shores of Maine.”24

What is most “Black” about H. Rap Brown’s pronouncements, in other words, is simultaneously what is most “white” about him: he, like Bo Diddley, Wild Nigger Bill, Davy Crockett, and Twain’s blustering raftsmen, is drawing on a multi-sourced, all-American tradition of vernacular self-aggrandizement. Cowboy Troy, too, draws on this tradition. “I Play Chicken With the Train” is scandalous not because it mixes “Black” rap with “white” country, but because, through the sheer force of unlikely-but-seamless juxtaposition, it forces us to acknowledge that those two musical styles, at least when they whoop it up, are brothers under the skin.

I’m Country Like That: Hick Hop, Hill Hop, and the King of Country Bling

Although he is arguably the most popular current purveyor of the hybrid genre known variously as country rap, hick hop, and hill hop, “Cowboy Troy” Coleman is neither the creator of the genre nor its only significant representative. His achievement is most usefully contextualized as one attempt among many to build a bridge between America’s two most popular and most seemingly irreconcilable musical forms. “In 1998,” according to Christopher John Farley, “for the first time ever, rap outsold what previously had been America’s top-selling format, country music. Rap sold more than 81 million CDs, tapes, and albums last year, compared with 72 million for country.” In one sense, the emergence of country-rap hybrids might have been anticipated: the 1990s were the decade in which the terms “multicultural” and “biracial” achieved currency, a decade capped off by the year 2000 census, in which respondents could, for the first time, self-identify as both white and Black. Rhythm Country and Blues (1994), a concept album which paired country stars like Willie Nelson, Conway Twitty, and Reba McIntyre in duets with R&B performers like Gladys Knight, Aaron Neville, and Natalie Cole, was a notable attempt to bridge the perceived gap—a precursor and parallel to the country/rap renaissance. By the same token, country and rap have achieved much of their contemporary popularity by configuring themselves in the national imagination as proudly (if not in country’s case overtly) racialized genres: the voice of unreconstructed southern pastoral and the rural white working class on the one hand, and the voice of inner-city frustration, gun-play, and rump-shaking Vegas-style fantasy on the other—Buddy Jewel’s “Sweet Southern Comfort” facing off with N.W.A.’s “Fuck tha Police.”25

Despite the varied and often occluded Black investments in country music, the music’s whiteness has asserted itself in a range of ways through the course of its long history, from the blackface routines enacted by George Hay, Jimmie Rodgers, and Gene Autry in the 1920s and 1930s to the late-1960s moment when, according to historian James N. Gregory, “country music provided the soundtrack for the Silent Majority,” South and North, in the face of rock-‘n’-roll integrationism. In 1968, Nashville’s Music Row “was practically a battlefield command post for George Wallace,” observes journalist Paul Hemphill; Wallace’s third-party Presidential candidacy recast the southern segregationist as a populist of national reach at precisely the moment Black Power politics were fueling Black urban unrest at multiple points on the compass. Those memories have lingered, for Blacks as well as whites. When race is at issue, the trope “country music” has often functioned much like the Confederate battle flag described by historian John M. Coski as the “expression of an ideological tradition.” “[The o]nly thing country about him is his cowboy hat,” insisted one of many irritable contributors to Cowboy Troy’s main discussion board at CMT.com, oblivious to the irony attendant on that prop of fabricated authenticity. “He has NOT created a new genre, until someone else follows (considering it takes more than 1 person or group to have a genre), which will never happen. Even his own website calls him a rapper. Is part of a bad-intention group called the ‘Muzik Mafia,’ which is trying very hard to pollute country . . . .” As sociologist Pierre Bourdieu notes, “In matters of taste more than anywhere else, all determination is negation; and tastes are perhaps first and foremost distastes . . . .The most intolerable thing for those who regard themselves as the possessors of legitimate culture is the sacrilegious reuniting of tastes which taste dictates shall be separated.”26

Self-appointed delegitimizers notwithstanding, country/rap hybrids have proliferated over the past decade. The transracial country west has been reconfigured as a dozen different contact zones, each betraying a different set of aesthetic preoccupations and racial investments. Many of them, surprisingly—or perhaps not—stage white incursions across the color line. Trace Adkins’s voyeuristic anthem “Honky Tonk Badonkadonk” (2005) envisions Black-white interchange as the re-enchantment of white female flesh with the help of a borrowed (Black) gaze, attitude, and vocabulary:

Now Honey, you can’t blame her

For what her mama gave her

You ain’t gotta hate her

For workin’ that money-maker

Band shuts down at two

But we’re hangin’ out till three

We hate to see her go

But love to watch her leave

With that honky tonk badonkadonk

Keepin’ perfect rhythm

Make ya wanna swing along

Got it goin’ on

Like Donkey Kong27

The rappers Keith Murray, LL Cool J, and Ludacris first introduced the phrase “badonkadonk” in “Fatty Girl” (2001); Missy Elliott’s “Work It” (2002) included the boast, “[S]ee if you can handle this badonk-a-donk-donk.” Adkins didn’t just sample a bit of rap vernacular into his raunchy country hit, but invoked a whole hip-hop-inflected attitude of female display and male connoisseurship, with a blues standard, Elmore James’s “Shake Your Money Maker,” thrown in for good measure. Adkins, a country star, anchors his sexualized gaze in honky-tonk workmanship and the dance it produces—i.e., in the ritual of call (his band’s performance) and response (the booty in question “keepin’ perfect rhythm”). The invocation of Donkey Kong, however—a popular Nintendo character modeled on King Kong—raises questions about such heavy white investments in Black cultural materials. The raunchy, late-night revelry evoked by Atkins arguably transforms him, at least in fantasy, into a jungle gorilla animated by a donkeyish phallic “swing.”

Insane Shane McKane, who calls himself “The King of Country Bling” and a purveyor of “redneck-rap,” fuses country and rap into a very different sort of double-edged burlesque, mocking—in his own boozy brags—both benighted southern whiteness and attitudinizing hip-hop Blackness, as though the idiot banjo player in Deliverance had decided to ventriloquize the voice of 50 Cent and started spitting out tin-eared rhymes. “The Nobel Peace o’ Ass Prize” on I Put the Ho in Hoedown (2004) is typical:

You know I deserve it, come on give it up

A cowboy like me knows how to fuck

You put a bone out, a dog’s gonna chew it

A woodpecker on a tree, you peck right through it

You put some booty in front of me, I’m gonna screw it

In more positions than I know what to do wit28

McKane’s rap is energized by roughly the same proportions of admiration, derision, and ideological confusion that animated blackface minstrels of another era. Blackness here registers as sampled vernacular (booty, kickin’, bitch, check that ass, ho), sexual signifying (“You put a bone out, a dog’s gonna chew it”), and hip-hop braggartry (“You can’t compete with me, you want a piece ‘a me”), but all of these materials are transformed into evocations of white trash idiocy. McKane seems to have found a way of balancing both poles of the mythic hillbilly—comic yokel and dangerous degenerate—on the fulcrum of an appropriated, reductive Black urban masculinity.

When African American artists participate in country rap hybrids, they, like Cowboy Troy, almost always participate from the “Black” side of the divide, which is to say they amalgamate or juxtapose their rap with “white” country inflections provided by others. The one notable exception is Vance Gilbert, an African American singer/songwriter and self-described “ex-multicultural arts teacher and jazz singer” from Philadelphia. It would be fair to say that a listener unfamiliar with Gilbert would, in a blind test, hear a “white” voice, and would place him in the programming niche he in fact occupies—a guitar-strumming product of the Cambridge, Massachusetts, New Folk scene and stage-fellow of Shawn Colvin, Martin Sexton, Patti Larkin, and Bill Morrissey. Gilbert’s “Country Western Rap” (1994) wittily addresses this dilemma by enacting a see-saw rapprochement between two racialized idioms, alternating his now-problematic “white folkie” voice with Jimmie Rodgers-style yodels, followed by burlesque renderings of a “Black” rap voice, complete with beat-box stylings. A fiddle-driven western swing groove alternates with low-down crunk to heighten the stylistic collision:

[sung to Western swing]

Well I was talkin’ to my manager about a new plan of attack

He says “You play great folk guitar, but don’t forget: you’re black!

Now here’s a new promotional angle that’ll put us on the map.

We’ll create a whole new genre, call it country western rap.

“Chorus:Yodelay-ee-hoo [beat box] [repeats]

Yodelay-ee-hoo-hoo-hoo . . . (Can’t touch this)

Lay-hee odelay-hee odelay-hee odelay-hee hoo

Now rap they’ve got New Kids on the Block, and country’s got Charley Pride

And that’s pretty multicultural if you put ’em side by side

But I could be the new breed, yeah . . . the one to fill the gap, mm hmmm

The best of the both, that’s the ticket: country western rap

[chorus]

[“Black” rap voice over crunk groove]

Well I was hanging at the crib (just chillin’), popped in a tape and my boy was killin’

He was (pumpin’ up a jam), I had to have this, ah who was it, it was Randy Travis, say (whoa)

Well it’s off to the record shop, hell I didn’t stop ’till my Visa was smokin’

I left Tower Records’ charge machine broke . . . yeah, boyeee . . .

Well I bought (Merle Haggard), Hank Williams too, my homeboy said (Whatcha tryin’ a do?)

I said Yo, bro, I don’t mean to be dissin’, but there’s beaucoup jams that I think we’ve been missin’

LL Cool J and Dolly Parton, Crystal Gayle and I’m just startin’

Reba McIntyre and MC Hammer, what a double bill it’s a bad mama jamma

Johnny Cash and Bobby Brown, yippie kai-yo kai-yay get down

With a fresh little jam that’s in between . . . it’s a little bit a both, if you dig what I mean

[chorus]29

Gilbert imagines the transracial country west not as a dance-inducing, community-building frontier breakdown, à la Cowboy Troy, but as a self-conscious postmodern collage, a comic rejoinder to race-driven expectations. Those expectations pressure him from both sides of the color line. His (presumptively white) manager sees “country western rap” as a shrewd and profitable way of heightening his Blackness, and in fact his Black vernacular voice erupts into the song the moment he begins listening to a Randy Travis tape. His (presumptively Black) homeboy back at the crib, on the other hand, is understandably dubious about Gilbert’s newfound obsession with twang—an obsession that immediately morphs into Gilbert’s roguish determination to forge the unlikeliest of duets between the country/western and rap pantheons circa 1994.

Eleven years separate “Country Western Rap” from “I Play Chicken With the Train.” It is tempting to counterpoise Gilbert’s facetiousness with Coleman’s good-natured swagger—a satire of rap braggadocio in the former case, actual rap braggadocio in the latter—and to read significance into the difference: a failure of the earlier historical moment to sustain country rap, with the 2000 Census and its national certification of bi- and multi-racialism as a watershed moment. The manifest absurdity of “I’m country like that” gives way to the empowered audacity of “Get you some of that.” But if the present investigation of America’s musical excluded middle has anything to teach us, it’s that we should begin with the concrete and particular, not with pre-digested understandings of America’s racial landscape. Vance Gilbert comes to the country rap project as a Cambridge-bred folkie responding to both idioms as a cultural outsider. His parodic distancing is, among other things, a way of asserting solidarity with a particular subculture that values such a stance. Troy Coleman comes to the same hybridizing project as a Dallas-born, Austin-bred rapper with Nashville-centered ambitions and wide-ranging tastes. He has cast his fate with a pair of adventurous white alt-Nashville producer/performers, he’s eager to synthesize his aesthetic influences, and he’s eager to find profitable common ground with modern honky-tonkers. The audience that remains unrepresented in Gilbert’s fantasy, it turns out, is the audience that Coleman conjures up, and is embraced by. Gilbert “could be the new breed . . . the one to fill the gap,” but Coleman is the one whose “[s]kills got you jumpin’ outch’a socks”; the one who has “already been on the CMAs,” has secured Tim McGraw’s approval, and gets the crowd to scream when he “stomp[s] the ground.” Race plays a crucial role here, but it does so by spurring both artists, albeit in somewhat different ways, to clear a space in which “Blackness,” even while summoned up, is playfully merged with its imagined Other in the interest of larger, fuller lives for all parties concerned.

Anyone who presumes to find a utopian moment within “I Play Chicken With the Train” must acknowledge, of course, that Coleman’s conservative electoral politics are strongly at odds with his progressive cultural politics. He was an outspoken supporter of the McCain-Palin ticket in its run against Barack Obama, and he called his appearance at the GOP convention in Minneapolis to sing the national anthem “the biggest thing that has ever happened to me.” “I’m conservative,” he told journalist Deborah Corey, “because I think it is important to at least be fiscally sound . . . . As a father and husband, I need to think about college (for my children) and taking care of my family . . . I support being a Christian and being pro-life because that makes sense to me as a husband and father.”30 Yet even here, in his public embrace of Christian conservatism, Coleman is playing an edgier game than might be apparent: married to a white woman, the father of biracial triplets, he’s using “family values” to normalize what the southern heartland has traditionally pathologized and criminalized. Is he, then, an abomination come to pollute country music with his “rap-junk” as the “white girls down front [dance] for him,” or a patriotic, God-fearing daddy? Or is he merely a canny performance artist who has figured out a profitable way of getting over? Troy Coleman, as Cowboy Troy, has navigated the shadowed open range of the transracial country west with a combination of brashness and finesse that rewards our attention, and deserves our respect.

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Adam Gussow is an associate professor of English and southern studies at the University of Mississippi. He is also a professional blues harmonica player and teacher, as well as a member of the Harlem blues duo “Satan and Adam.” His essay “Where Is the Love? Racial Wounds, Racial Healing, and Blues Communities” was reprinted in Southern Cultures: The Fifteenth Anniversary Reader, 1993–2008.

NOTES

- Quoted in Leon E. Wynter, American Skin: Pop Culture, Big Business, and the End of White America (New York: Crown Publishers, 2002), 13-14; Douglas Martin, “Alonzo Pettie, 93, Creator of a Black Rodeo,” obituary in the New York Times, August 12, 2003, Section B7, quoted in Michael McCall, “Cowboy Troy,” People 63, no. 21 (May 30, 2005), 43.

- Journalist Tom Breihan called Cowboy Troy “the whitest-sounding nonwhite rapper since E-40.” “Country-Rap: A Secret History,” Village Voice blog entry (June 17, 2008).

- Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror: Or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York: Routledge, 1990), 34.

- Kandia Crazy Horse, “Revolutions: Music: Cowboy Troy,” Vibe (July 2007); Cowboy Troy, “How Can You Hate Me,” Black in the Saddle (Warner Brothers Nashville—WASE 43233, 2007).

- Loco Motive sold 51,273 units in the week of June 4, 2005. See Shelly Fabian, “On the Charts: Billboard’s Country Singles and Albums,” About.com: Country Music, http://countrymusic.about.com/od/charts/a/blcharts060405.htm (accessed December 10, 2007); Josh Tyrangiel, “The Battle of Troy,” Time 165, no. 22, May 30, 2005; Mike Jahn, “‘Hick Hop,’ Country, Metal and Cowboy Troy,” The Ancient Rocker (2005), http://www.geocities.com/theancientrocker/cbt (accessed December 10, 2007); BeamBeam1, “Accurate description of CBT!” Cowboy Troy Main Board, posted July 18, 2005, CMT.com, http://www.cmt.com/artists/az/cowboy_troy/message_board.jhtml?c=v&t=574482&m=3750904&o=0&i=0 (accessed July 21, 2005); Tyrangiel, “The Battle of Troy”; Gail Dines, “King Kong and the White Woman: Hustler Magazine and the Demonization of Black Masculinity,” in Not For Sale: Feminists Resisting Prostitution and Pornography, ed. Rebecca Whisnant and Christine Stark (Australia: Spinifex Press, 2005), 91.

- Jennifer Ludden, “Interview: Singer ‘Cowboy Troy’ Coleman Talks about Hick-Hop,” National Public Radio, June 19, 2005; Troy Coleman/John Rich/Angie Aparo, “I Play Chicken With the Train,” Cowboy Troy, Loco Motive (Warner Brothers—Raybaw 49316-2, 2005); Vivien Green Fryd, “‘The Sad Twang of Mountain Voices’: Thomas Hart Benton’s Sources of Country Music,” in Reading Country Music: Steel Guitars, Opry Stars, and Honky-Tonk Bars, ed. Cecelia Tichi (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), 268-69, 272.

- Patrick Joseph O’Connor, “Cowboy Blues: Early Black Music in the West,” Studies in Popular Culture 16, no. 2 (April 1994): 96. See also Wald, Escaping the Delta, n. 16; Louis M. Kyriakoudes, “The Grand Ole Opry and the Urban South,” Southern Cultures 10, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 76, 78-79; David C. Morton and Charles K. Wolfe, DeFord Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993), esp. 60, and Elijah Wald, Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 47, 52; Pamela E. Foster, My Country, Too: The Other Black Music (Nashville, TN: Publishers Graphics, 2000), 9, 12, passim; George H. Lewis, “Lap Dancer or Hillbilly Deluxe? The Cultural Constructions of Modern Country Music,” Journal of Popular Culture 31, no. 3 (Winter 1997); Dunkor Imani, “Country Music Gets Some Color,” Black Issues Book Review 2, no. 5 (September/October 2000); Foster, My Country, Too, 10; Nate Guidry, “Country Music’s Blacklist,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 18, 2001; Daniel T. Stein, “‘I Ain’t Never Seen a Nigger’: The Discourse of Denial in Lee Smith’s The Devil’s Dream,” European Journal of American Culture 22, no. 2 (May 2003): 150; Foster, My Country, Too, 10, 80; Peter Applebome, “Country Greybeards Get the Boot,” New York Times, August 21, 1994, Arts & Leisure, sec. 2, p. 1; Wald, Escaping the Delta, 47-53, 97; Foster, My Country, Too, 87, 39-40; Berry quoted in Bernard Weinraub, “Sweet Tunes, Fast Beats and a Hard Edge,” New York Times, February 23, 2003, Sunday. Sec. 1, p. 1.

- Phyllis Stark, “Cowboy Troy’s Wild Ride,” Billboard 117, no. 23 (June 4, 2005), 51; Ken Tucker, “Bigger and Richer,” Billboard.com, April 14, 2007 (accessed via LexisNexis on January 10, 2010).

- Christopher Waterman, “Race Music: Bo Chatmon, ‘Corrine Corrina,’ and the Excluded Middle,” in Music and the Racial Imagination, ed. Ronald Radano and Philip V. Bohlman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 167; James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 175.

- Ludden, “Interview: Singer ‘Cowboy Troy’ Coleman Talks about Hick-Hop.”

- Tyrangiel, “The Battle of Troy”; Brian Mansfield, “‘Hick-hop’ Pioneer Troy Wields a Unique Brand,” USA Today, March 20, 2005, http://www.usatoday.com/life/music/news/2005-03-20-cowboy-troy_x.htm (accessed May 22, 2005); Farai Chideya, “The Hick-Hop of Cowboy Troy,” News & Notes (January 10, 2007).

- John Gerome, “Cowboy Troy Offers ‘Hick-Hop,'” The (South Mississippi) Sun Herald, June 23, 2005, http://www.sunherald.com/mld/thesunherald/entertainment/11962014.htm (accessed July 20, 2005); Martin Hodgson, “The Hidden Faces of Country,” Observer Music Monthly, Guardian.co.ukonline (July 16, 2006).

- Paul Gilroy, Against Race: Imagining Political Culture Beyond the Color Line (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000), 181; Ludden, “Interview: Singer ‘Cowboy Troy’ Coleman Talks about Hick-Hop”; “Artists to Watch,” Rolling Stone 975, June 2, 2005: 20; Ernest Jasmin, “Is Nothing Sacred? Country Meets Hip-Hop,” The (Tacoma) News Tribune, July 15, 2005, http://www.thenewstribune.com/ae/story/5023384p-4583233c.html (accessed July 20, 2005).

- Foster cites considerable evidence for this attitudinal claim in My Country, Too: The Other Black Music, even as she rebuts it in a range of ways. See also John Marks, “Breaking a Color Line, Song by Song,” U.S. News & World Report 126, no. 14 (April 12, 1999): 4; Blake Allmendinger, Imagining the African American West (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 81-82; Snoop Dogg, “My Medicine,” Ego Trippin’ (Doggystyle/Geffen, 2008).

- Lewis, “Lap Dancer or Hillbilly Deluxe?” On the subject of racial stratification and transracialism within contemporary country dancehall culture, see Jocelyn R. Neal, “Dancing Around the Subject: Race in Country Fan Culture,” The Musical Quarterly 89, no. 4 (2006), published online on December 4, 2007.

- See Christie Bohorfoush, “The AngryCountry Interview: Cowboy Troy,” August 3, 2005, http://magazine.angrycountry.com/article.php?story=20050803223557953, (accessed December 10, 2007); Chideya, “The Hick-Hop of Cowboy Troy.”

- Margo Jefferson, “My Town, Our Town, Motown,” The New York Times, March 5, 1995, sec. 2, p. 1; Fahamisha Patricia Brown, Performing the Word: African American Poetry as Vernacular Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 83.

- Waterman, “Race Music,” 167.

- For connections between Shine and Dolemite and the rap tradition, see Imani Perry, Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004), 30; Mimi Clar Melnick, “‘I Can Peep Through Muddy Water and Spy Dry Land’: Boasts in the Blues,” in Mother Wit From the Laughing Barrel: Readings in the Interpretation of Afro-American Folklore, ed. Alan Dundes (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973), 267-268; Adam Gussow, Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 171.

- Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought From Slavery to Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 400-401.

- Adetayo Alabi, “‘I Am the Hunter Who Kills Elephants and Baboons’: The Autobiographical Component of the Hunters’ Chant,” Research in African Literatures 38, no. 3 (2007): 13-23, http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/research_in_african_literatures/v038/38.3alabi.html (accessed September 30, 2007); Geneva Smitherman, Talkin and Testifyin: The Language of Black America(1977; repr., Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1985), 78; Brown, Performing the Word, 87.

- James Kirke Paulding, The Lion of the West, retitled The Kentuckian, or A Trip to New York, ed. James N. Tidewell (1831; repr., Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1954), 21; Elliott J. Gorn, “‘Gouge and Bite, Pull Hair and Scratch’: The Social Significance of Fighting in the Southern Backcountry,” The American Historical Review 90, no. 1 (February 1985): 32; Christian K. Messenger, Sport and the Spirit of Play in American Fiction (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981), 60-61; Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi (1883; repr., New York: Viking Penguin, 1984), 53.

- On the plantation origins of the breakdown, see Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 78, 226 (n. 126); Constance Rourke, American Humor: A Study of the National Character (1931; repr., New York: Anchor Books, 1953), 79-80; Leon E. Wynter, American Skin: Pop Culture, Big Business, and the End of White America (New York: Crown Publishers, 2002), 13.

- H. C. Brearley, “‘Ba-ad Nigger,'” in Mother Wit From the Laughing Barrel: Readings in the Interpretation of Afro-American Folklore, ed. Alan Dundes (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973), 579; Brown, Performing the Word, 89.

- Christopher John Farley et al., “Hip-Hop Nation,” Time 153, no. 5, February 8, 1999.

- Gregory, The Southern Diaspora, 313; John M. Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: America’s Most Embattled Emblem (Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 301; commenter “BeamBeam1,” “Accurate description of CBT,” Cowboy Troy Main Board, CMT.com; Bethany Bryson, “‘Anything But Heavy Metal’: Symbolic Exclusion and Musical Dislikes,” American Sociological Review 61 (October 1996): 886.

- Trace Adkins, “Honky Tonk Badonkadonk,” http://www.cowboylyrics.com/lyrics/adkins-trace/honky-tonk-badonkadonk-15326.html (accessed December 11, 2007).

- Insane Shane McKane, “The Nobel Peace o’ Ass Prize,” I Put the Ho’ in Hoedown (Cockfight Records, 2004). Lyrics transcribed by Adam Gussow.

- Biographical information from vancegilbert.com; Vance Gilbert, “Country Western Rap” (Self published, 1994). Lyrics transcribed by Adam Gussow and reprinted here with permission.

- Marco R. della Cava, “Grand Old Party Time,” USA Today, September 4, 2008; and Deborah Corey, “Cowboy Troy: Q&A—Outside the Box,” The Washington Times, October 17, 2008.