I don’t know when exactly I learned that Tennessee was the deciding vote to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment of the US Constitution, the suffrage amendment that expanded women’s access to the ballot box. I think this history entered my consciousness in August 2006 when I saw a group of mostly white women in period attire—long dresses in various shades of white, cloche hats, and replica “Votes for Women” sashes—dedicating a monument to three white Tennessee suffragists, Lizzie Crozier French, Anne Dallas Dudley, and Elizabeth Avery Meriwether, at Market Square, a prominent downtown location in Knoxville. I had just returned to the city after earning my master’s degree in women’s history from Sarah Lawrence College, the first to offer such a degree, beginning in 1972. Most people who learned of my studies assumed I was a walking encyclopedia of Women’s Achievements, such as Woman Suffrage. But I didn’t care for the march, the historic garb, or the monument. Partly, my detachment had to do with my own search for history that spoke to the moment.

I came of age in the years that the US invaded Afghanistan and Iraq and soon joined some of the largest peace protests since the Vietnam War. In 2006, a wave of immigrant rights demonstrations crested across Tennessee in response to the spike of ICE raids on Latinx workers at local factories and industrial farms. In the working-class neighborhood where I lived, lawn signs advertised subprime loans from companies that we now know targeted Black women. At the community college where I taught, my classes were filled with middle-aged women recently laid off from their jobs at furniture factories. My training in women’s history helped me understand the gendered components of all of these events. Before long, I was searching for interpretations of history that, as literary scholar Carolyn Steedman describes, could help to “give current events meaning.”1

I have committed my career to southern women’s history, and I understand the power of public memorials for producing historical memory. The women who fundraised for the suffrage statue at Market Square yearned for more Tennesseans to understand how women changed their state and national history, a worthy goal. Yet their memorial, not to mention centennial celebrations of the suffrage amendment, contains and simplifies women’s history. What is deemed “political” is too often confined to voting; woman suffrage cannot be easily disentangled from other contemporary crusades, most notably the temperance movement and anti-lynching campaigns. Reflecting on the centennial of the woman suffrage amendment, historian Martha S. Jones recently commented: “Anniversary dates are an opportunity to teach history to a broader public. . . . But if we give in to the tug of mythmaking and sanitization that these sort of rituals require, we are doing something else.”2

Most people who learned of my studies assumed I was a walking encyclopedia of Women’s Achievements.

Often the “something else” papers over the uglier side of suffrage and limits history to milestone events. Take, for example, one of the quotations inscribed at the base of the Tennessee suffrage statue by Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of famed abolitionist and suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton: “All honor to women, the first disenfranchised class in history who unaided by any political party, won enfranchisement by its own effort alone, and achieved the victory without the shedding of a drop of human blood.”3

On the face of it, the quotation suggests a noble political victory by American women, one that ties Tennessee suffragists to a national campaign. It also reveals the thinking of a woman whose political goals were enmeshed in the racist politics of the day. When Blatch, a New Yorker, claimed that women, by whom she most likely meant white women, were the “first disenfranchised,” she eclipsed freedpeople’s struggle for political power in the Reconstruction South. Like her mother, Blatch believed that the Fifteenth Amendment, which extended suffrage to men without regard to race, placed white women at the mercy of “unenlightened” Black men, who were less deserving of the vote than elite white women.4

Blatch is worth remembering in the South for what her approach to suffrage tells us about politics in early twentieth-century America. Like many, she saw the South as an important battleground for white women’s suffrage, not necessarily democracy. In a meeting with President Wilson, she sought to assuage his and other white political leaders’ fears that extending the vote to women would strengthen the African American vote, arguing that “enfranchisement of women in the South would increase not decrease the proportion of white to black voters.”5

Black suffragists sought political power in Tennessee, too. Their stories show how they navigated multiple sources of oppression. For them, the suffrage campaign was part of a longer struggle for the rights of Black men and women, before and after ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Juno Frankie Pierce, a Black woman from Nashville born to formerly enslaved parents, grew into a prominent leader in the Black women’s club movement, characterized by the expansion of Black women’s associations in the early twentieth century that nurtured collective consciousness and sought political, social, and economic reforms toward full equality. In Nashville, Pierce led efforts to establish schools for Black girls and to keep so-called delinquent girls out of jails meant for adults. In 1920, she joined with white suffragists to lobby the Tennessee legislature for the vote. As the only Black woman permitted to address state officials during the 1920 suffrage convention, she implicitly addressed fears that female suffrage would threaten white supremacy. Black women would “stand by the white women,” but were also asking for a “square deal”—the right to continue their racial uplift work in the form of education and child welfare. Pierce’s likeness is featured alongside four white suffragists in Nashville’s own suffrage memorial, suggesting a parallel struggle, or at least a similar impetus for joining the suffrage cause. Pierce, however, walked the white supremacist line not because of sisterly bonds with white women, but to secure resources for Black women and girls.6

After the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Black women attempted to register to vote across the South. They faced harassment, threats, and violence; they found little support from predominantly white women’s rights groups like the League of Women Voters. It would take decades and many more voting rights campaigns, along with economic boycotts and direct-action protests, to chip away at white political power in the South. As conveyed in an article in this issue by historian Adriane Lentz-Smith, it also took acts of defiance at significant cost to Black women’s lives.

The history of suffrage in the South—indeed, the nation—is messy and fraught, and more contentious than is typically remembered. As historian Crystal N. Feimster has shown in her dual biography of political activists Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Rebecca Latimer Felton, the history is one of white supremacy and women’s rights, freedom and oppression, and how these contradictions intertwined in the lives of southern women. Black suffragists like Wells-Barnett fought for the vote as part of broad struggles for civil rights and to end lynching and racial terror. White women, such as Rebecca Latimer Felton, charted a path for white women’s independence through white female supremacy. Other white southern women, trained in the suffrage movement and influenced by Black-led anti-lynching campaigns in the 1930s, coordinated to challenge racial terror. They argued that white men implicated white women in lynching when they claimed to protect their womanhood—thus lynching was an issue they must take up. This fuller history of suffrage and women’s rights in the South does not lend itself easily to marches and celebrations, cocktail hours or galas. Nonetheless, it is our history.7

This fuller history of suffrage and women’s rights in the South does not lend itself easily to marches and celebrations, cocktail hours or galas. Nonetheless, it is our history.

This issue of Southern Cultures takes the centennial as a springboard to reflect on political power, women’s activism, and civic cultures. From the point of view of women who lived, worked, struggled, created in, and sometimes fled the South, the authors here explore women’s intellectual and embodied relationship to place. We begin fittingly with an essay by Beth Kruse, Rhondalyn K. Peairs, Jodi Skipper, and Shennette Garrett-Scott about the Black political culture in North Mississippi that shaped pioneering journalist, civil rights activist, and suffragist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who posthumously received the Pulitzer Prize this past spring. Her legacy is carried forth in contemporary protests for racial justice, the search for truth, and in bold defiance of racialized sexual and gender codes.

Why the “Women’s Issue”?

If the Nineteenth Amendment is a starting place for this issue, the 1960s and ’70s are the crux of it—these decades birthed women’s history as a field and, arguably, a distinctly southern women’s history. The title draws inspiration from a dynamic print culture that flourished in the South in the 1960s and 1970s, the era of liberation movements. With women at the helm as guest editors, journals and underground publications across the region and nation printed special “women’s issues.” Our issue follows in that spirit but, unlike those from the past, it is not committed to a binary model of gender (frequently coded as white), as the title may suggest. Rather, the authors here consider how women in the South—including Black, Latina, queer, lesbian, trans, working-class, and white—experienced, challenged, and navigated notions of southern womanhood, a historically specific and, often, contradictory ideological process.8

With women at the helm as guest editors, journals and underground publications across the region and nation printed special “women’s issues.” Our issue follows in that spirit but, unlike those from the past, it is not committed to a binary model of gender.

Among the first “special issues” was motive, a journal of the Methodist Student Movement published in Nashville in 1969. It became a touchstone for young, progressive white women in the South. The editors worked with feminist activists Joanne Cook, Robin Morgan, and Charlotte Bunch to guest edit an issue “on the liberation of women.” The guest editors explained in the journal’s pages that they “coordinated, cajoled, and commandeered” and offered “an occasional ultimatum” in the process. Their issue made a splash. One woman in Ohio described how a coworker gave her the publication, “and Dayton was never the same!” Yet, by one editor’s own admission, the issue was “lily-white and middle-class” in both the authors represented and issues covered.9

The following year, Third World Women’s Alliance, whose members authored the now-classic Combahee River Collective statement, published Black Woman’s Manifesto. In it, Black civil rights and feminist activists Eleanor Holmes Norton and Frances Beal, both of whom had been members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), wrote two of the essays. Although not from the South, their activism and their essays were in conversation with the southern Civil Rights Movement. Norton had volunteered as legal counsel for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and Frances Beal, who founded the SNCC Black Women’s Liberation Committee (which later became Third World Women’s Alliance), engaged with “Sex and Caste,” a manifesto about sexism in SNCC authored by white SNCC activists Mary King and Casey Hayden.10

Lesbian feminist activists were among the first to start their own literary and activist publications in the South. For instance, Feminary, a lesbian feminist journal printed by a collective in North Carolina, began as an activist newsletter in 1969 and eventually became a literary journal devoted to “queer[ing] the South” and examining “the material conditions of our lives from an anti-racist lesbian and feminist perspective,” according to Mab Segrest, one of the collective’s members. The Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA), featured in Rachel Gelfand’s essay, created a newsletter borne partly of their frustration with the lack of inclusion in gay and feminist groups in Atlanta.11

Throughout the 1970s, women continued to guest edit special “women’s issues,” providing us a window into how women’s liberation emerged in the South. In 1974, women guest edited the Appalachian regional journal Mountain Life & Work and covered topics that animated poor and working-class women’s lives, from the impact of occupational disease to welfare rights. In the Great Speckled Bird, a leftist newspaper out of Atlanta, predominantly white women authors argued in the 1976 “Women’s Issue” for an anti-imperialist, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist women’s liberation movement. Notably, these special issues rarely or only occasionally included writers of color, even as their articles increasingly examined the intersections of race, class, and gender in women’s lives.12

At the core of many of these publications was an impulse to document progressive women’s activism in the South, past and present. From the vantage point of burgeoning women’s liberation movements, women writers and editors traced a feminist history for themselves, one that diverged from the nineteenth century’s Seneca Falls suffrage tradition and rooted the birth of feminist consciousness in the very places that activists called home. They documented women’s activist history, examined women’s participation in radical southern movements, and debated the meaning of women’s liberation in a region also dismantling Jim Crow segregation. Discourse and disagreement were of course part of the process. Many women started from “opposite ends of the spectrum,” as Black civil rights activist Cynthia Washington explained in an essay on white and Black women’s distinctive experiences of sexism. There were no easy answers about how to dismantle patriarchy and the vestiges of Jim Crow, or how women’s liberation related to other movements for social change, but women’s intellectual energies fueled significant debates about how to best build visionary campaigns to confront systemic power.13

One of the women’s issues most committed to mapping a southern feminist history, which included Washington’s essay, appeared in 1977 when the journal Southern Exposure published the special issue “Generations: Women in the South.” Founded in 1973 by veteran southern activists, the journal covered social and political issues in the South. The editors’ position was thoroughly rooted in recovering a radical political tradition in the region that had long been overlooked.

The “women’s issue” of Southern Exposure, along with other underground and leftist publications, undermines assumptions that feminism was not a feature of southern movements. Lively debates within the pages of print materials, moreover, point to how racism and class oppression informed women-led movements for liberation—activists ignored these issues at their own peril. The history of women-led movements in the 1960s and ’70s also reveals how debate and conflict were (and are) fundamental to movements. The very existence of publications whereby women took over print media typically controlled by men, and the range of definitions of what counted as a “women’s issue,” suggest tensions over how to create a more just society.14

Where we look for and where we find women’s history matters.

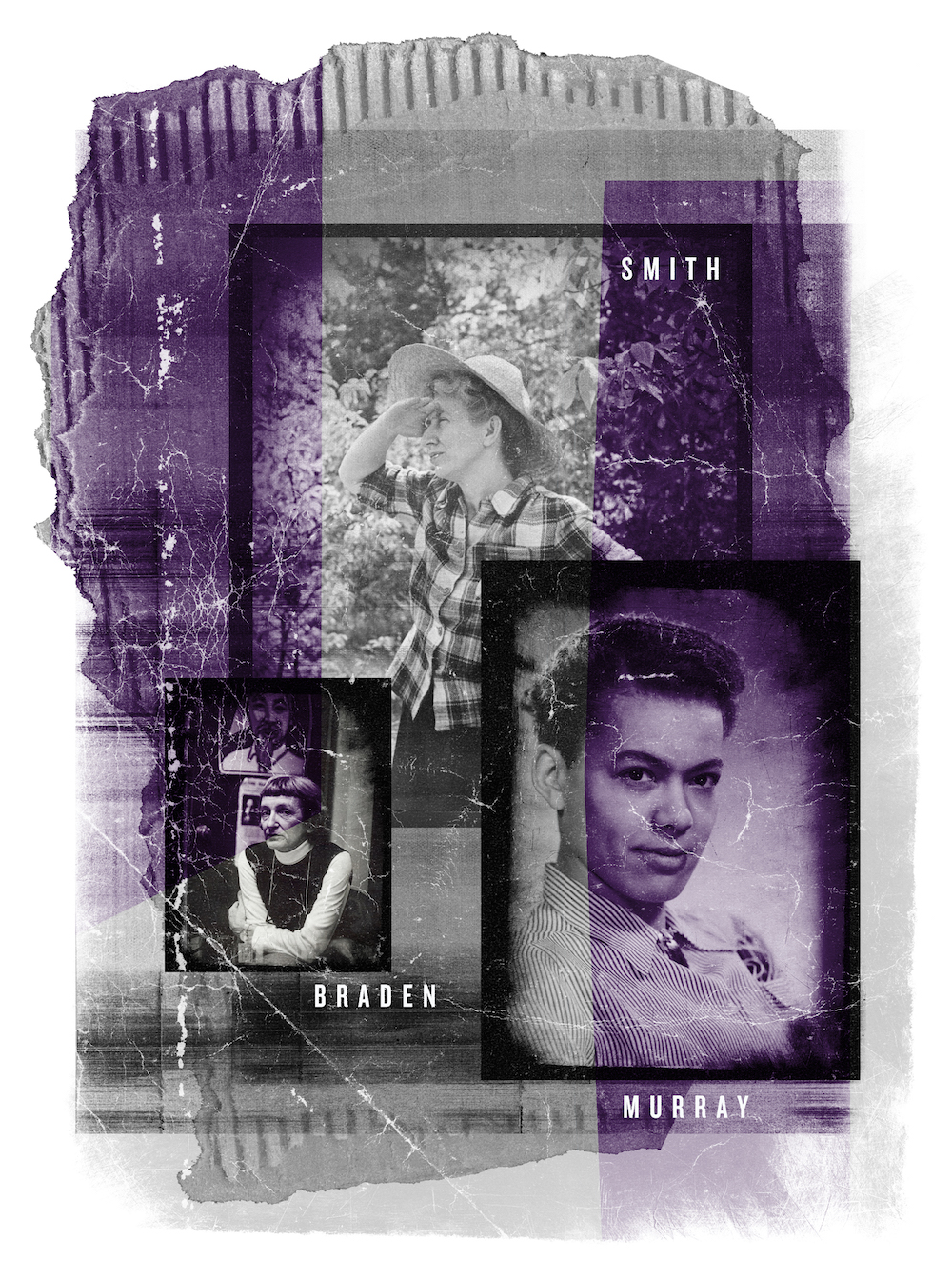

Where we look for and where we find women’s history matters. The editors of the Southern Exposure issue traced their roots to activist Pauli Murray, who argued that she must always be concerned with racial and sexual liberation because “the two meet in me,” and writer and social critic Lillian Smith, who wrote a searing memoir that she described as a confession about coming of age in the web of white supremacy. We now understand how Murray and Smith’s queerness was fundamental to their social critiques and activism. The editors printed leftist and civil rights activist Anne Braden’s letter, warning white feminists to always bring racial analyses to their understandings of sex oppression. They published segments of stories by southern working-class women that had been documented at the Southern Summer School for Women Workers in the 1930s. The Southern Exposure editors traced their own politics to a tradition “of Southern women as warriors against the status quo.” By identifying southern women who had relentlessly examined interlocking systems of power along lines of race, gender, class, and sexuality, and who had led movements for labor and civil rights, they mapped possibilities for their own time.15

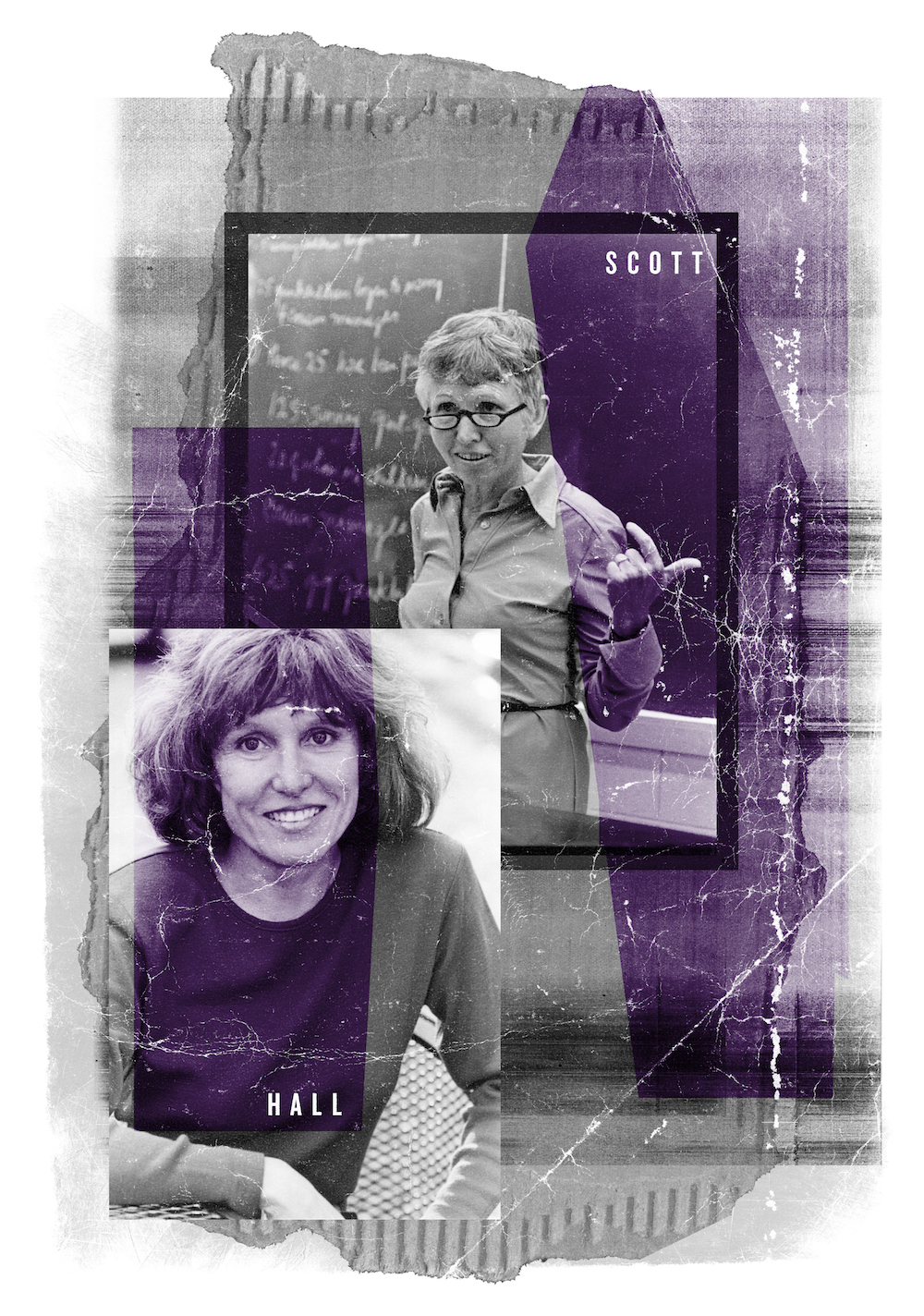

The 1977 issue was coedited by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, a historian of women and the South a few years into her faculty position at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who would, thirty years later, become my mentor. Among the first cohort of women faculty members at the university, she founded the Southern Oral History Program (SOHP). Early on, Hall, along with faculty and students affiliated with the program, interviewed both known and unknown women activists about their involvement in militant labor, civil rights, and women’s movements of the early twentieth century. Many of those interviews appeared in Southern Exposure, including excerpts from an interview with Pauli Murray, conducted by historian Genna Rae McNeil, in the women’s issue. This special issue of Southern Cultures also features the work of SOHP field scholars who document contemporary movements for voting rights in North Carolina and the memory of suffrage, centering the stories of Black and Indigenous women and Latina immigrants.

A few years after the Southern Exposure special issue, Hall joined trailblazing southern women’s historian Anne Firor Scott to write the first essay on southern women’s history. While southern historians had overlooked gender analysis, leading women’s historians, focused on the Northeast, had adopted conceptual frames that did little to explain the diversity of women’s experiences in the South. The roots of that scholarly work are clear in the essays and bibliography published in the 1977 issue—the bestselling in the journal’s run.16

This Southern Cultures issue follows in the tradition of bringing into focus women in the South who have blazed paths for political and social power. Some of the women featured here, such as Alice Walker, whose relationship to the South Keira V. Williams examines, also appear in that issue of Southern Exposure. Along with people, similar themes emerge, including, for example, histories of racialized gender violence in the South. If a reader were to compare the two journals, she would also notice similarities in what is left out: most notably the women who held and hold tight to white male patriarchy and nativism, whose politics and impact Elizabeth Gillespie McRae captures brilliantly in her recent book Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy. More studies attentive to the role of white southern women’s political power and involvement in the backlash to movements for democracy are needed.17

Building on the trailblazing “women’s issues” of the past, this issue offers a more capacious understanding of the women who have been at the forefront of change; how they perceived and defined women’s issues; and how others forged a politics from the margins. Many of the authors here, among some of the most exciting scholars of women, gender, and sexuality, are rewriting histories of the US South. Their goal is not simply to be more inclusive, but to reinterpret southern and women’s history through significant analyses of gendered and racialized power in southern politics and society. Their studies reconsider boundaries, perhaps key among them the racial binary that has long excluded Indigenous and immigrant women as key players on the stage of southern history. They ask us to consider the relationship between queer, trans, and cis women’s histories to deepen our understanding of southern culture and politics. By honing their analyses of movements for political and social power across time, from suffrage to anti-lynching, civil rights to women’s liberation movements, they mold histories that inform present-day struggles. Today’s scholars of women, gender, and sexuality in the South ask us to consider how our collective understanding of gender-based progressive movements—the triumphs and tragedies, victories, defeats, and half-won battles—aid or circumscribe our visions of a more just future. The essays in this issue map a history of women’s everyday lives, and their political, social, and cultural influences in the South, pointing a way forward.

Today’s scholars of women, gender, and sexuality in the South ask us to consider how our collective understanding of gender-based progressive movements—the triumphs and tragedies, victories, defeats, and half-won battles—aid or circumscribe our visions of a more just future.

As we prepared to go to press, uprisings in response to Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin killing George Floyd, a Black man accused of a petty crime, on May 25, have rocked the nation. For two straight weeks, multiracial throngs swarmed into the streets in every corner of the country, from major cities to small southern towns, demanding that city governments defund the police and take immediate steps to undo racist systems. They did so against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has rendered visible in the starkest terms how African Americans bear the brunt of racial and gender discrimination, economic inequality, and state-backed violence. Nowhere is that more evident than in the killing of Breonna Taylor, a Black woman and frontline worker, who was shot by police in her home on March 13 in Louisville, Kentucky, and whose story did not garner national attention until after the calls for justice for George Floyd. We also see it in the police killing of Tony McDade, a Black transgender man in Tallahassee, Florida, two days after Floyd’s death. And in the life and death of Brayla Stone, a Black transgender girl who was murdered in Little Rock, Arkansas, on June 25, the seventeenth reported violent death of a transgender or gender non-conforming person in 2020 to date.18

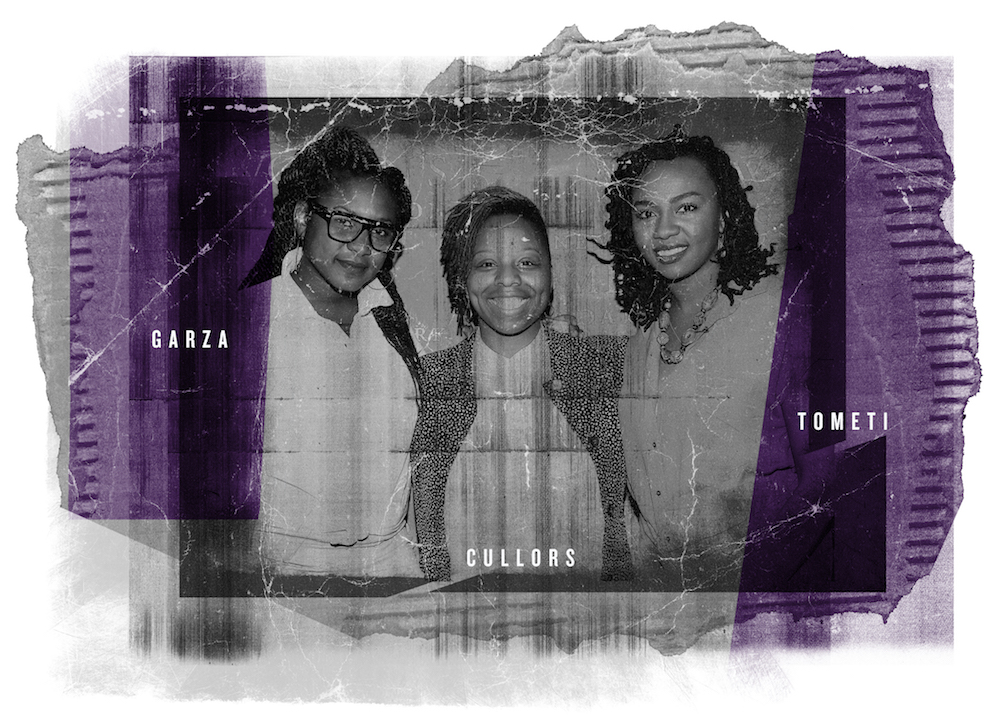

The massive uprisings today reveal in part the maturation of the Black Lives Matter movement cofounded by three Black women who identify as artists, transnational feminists, and queer freedom dreamers and fighters—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. In the South, Black women in particular have been organizing and sustaining the networks that have created the conditions for recent protests. They have fostered communities of care, mutual aid networks, and bail funds. As Louisiana native and Black feminist scholar Brittney Cooper recently observed, Black women activists did not suddenly emerge “in the middle of a pandemic.” Rather, they have been the “deep thinkers and theorists” who have assembled the tools to “actually build a society for the common good.” May we all commit to building with them.19

This essay appears in the Women’s Issue (vol. 26, no. 3: Fall 2020), which Jessica Wilkerson also guest edited. Use code 01SC30 at checkout to receive 30% off the issue/shipping total.

Jessica Wilkerson is associate professor and Stuart and Joyce Robbins Chair of History at West Virginia University. She is the author of To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice (Illinois Press, 2019) and is currently working on a book about feminisms in the American South.NOTESImage Credits

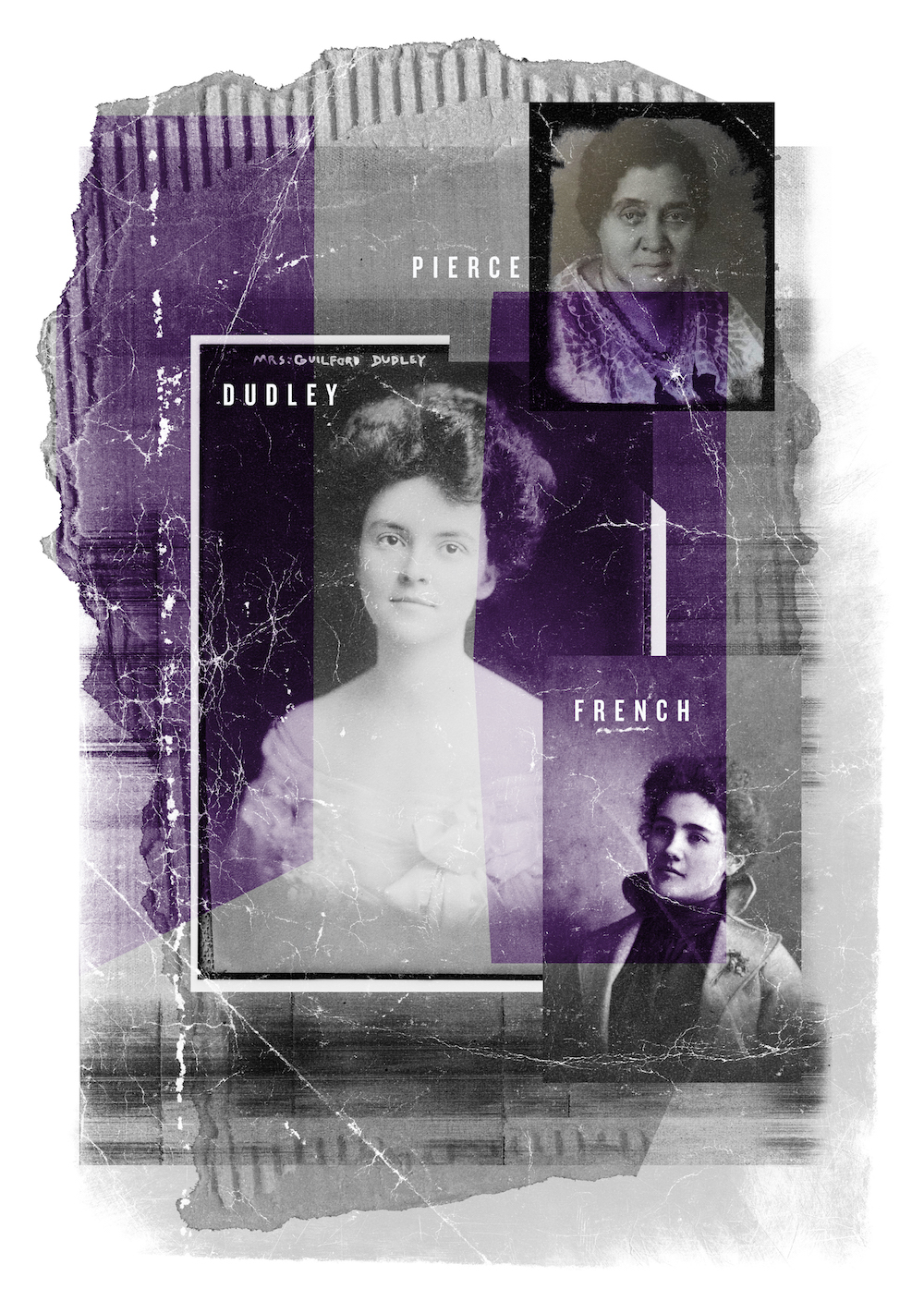

Collage 1

- Lizzie Crozier French, ca. 1890. Courtesy of the C. M. McClung Historical Collection, Knox County Public Library.

- Anne Dallas Dudley, ca. 1917. Courtesy of the Bain News Service Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

- Juno Frankie Pierce, n.d. Courtesy of the First Baptist Church Capitol Hill, Nashville, Tennessee.

Collage 2

- Ida B. Wells-Barnett, ca. 1893, by Mary Garrity. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

- Rebecca Latimer Felton, ca. 1922. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

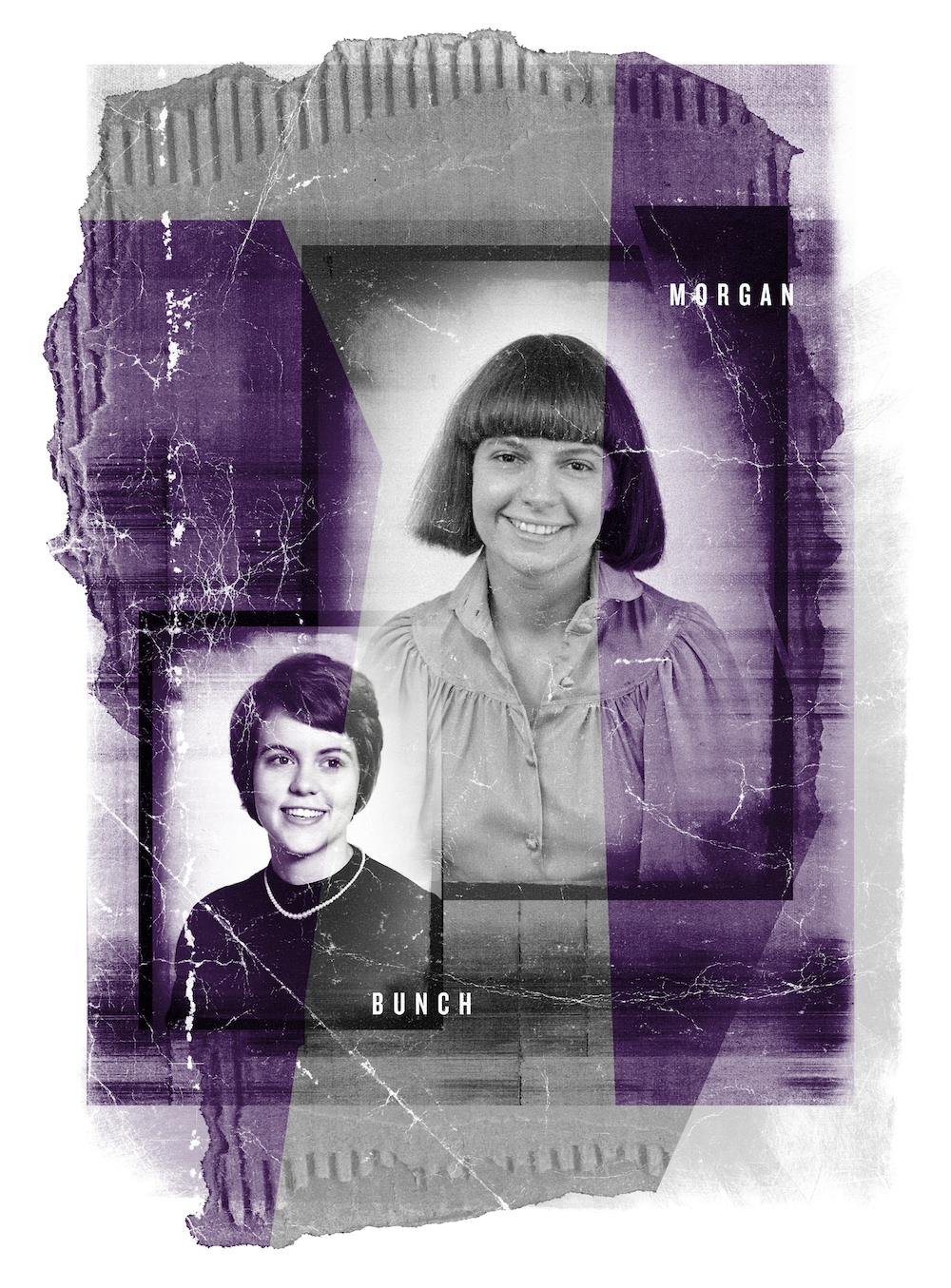

Collage 3

- Robin Morgan, August 6, 1977. Courtesy of Bettman/Getty Images.

- Charlotte Bunch, student photo, Duke University, 1965. Courtesy of Charlotte Bunch.

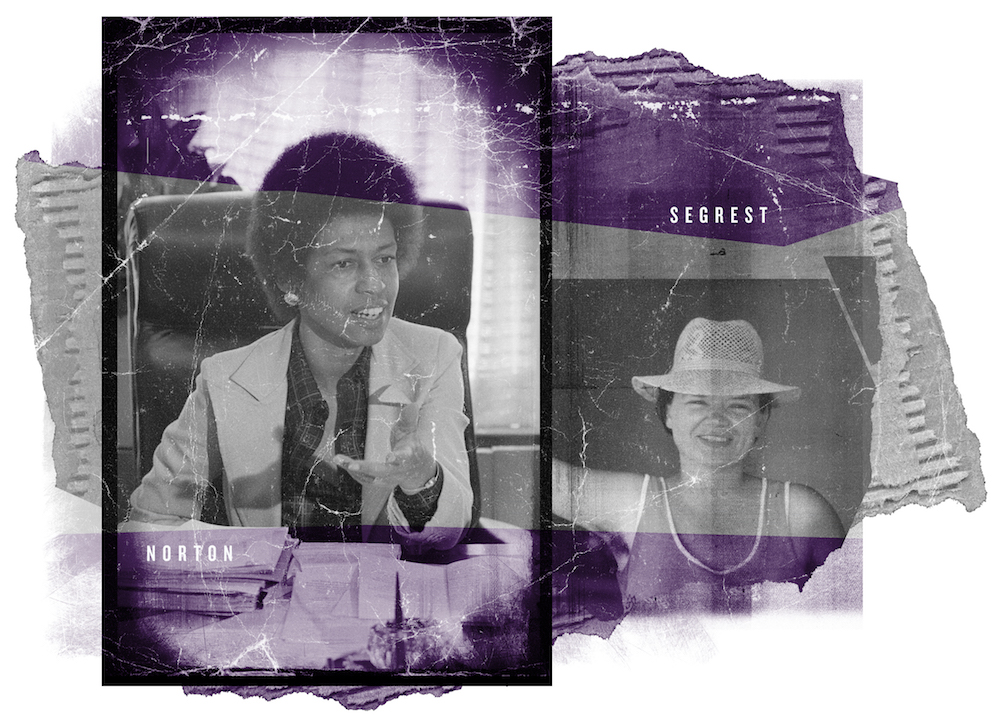

Collage 4

- Eleanor Holmes Norton, Committee of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, July 28, 1977, by Marion S. Trikosko. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

- Mab Segrest, 1979, photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Mab Segrest Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University. Reproduced by permission of Mab Segrest.

Collage 5

- Lillian Smith, Laurel Falls Camp, Clayton, Georgia, ca. 1940. Courtesy of the Vanishing Georgia Collection (rab356), Georgia Archives.

- Anne Braden. Courtesy of the University of Louisville Anne Braden Institute for Social Justice Research.

- Pauli Murray, ca. 1940. Courtesy of the Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo.

Collage 6

- Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, ca. 1980. Courtesy of Jacquelyn Dowd Hall.

- Anne Firor Scott, October 15, 1985. Courtesy of the Duke University Archives.

Collage 7

- Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, May 14, 2015, by Jemal Countess. Courtesy of Getty Images for the New York Women’s Foundation.

Notes

- Carolyn Kay Steedman, Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 5.

- “Interchange: Women’s Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote,” Journal of American History 106, no. 3 (2019): 662–694, 684.

- Tennessee Woman Suffrage Memorial website, accessed July 1, 2020, http://tnwomansmemorial.org/.

- Ellen Carol DuBois, Harriot Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 62.

- DuBois, Harriot Stanton Blatch, 197. For the roots of white suffragists’ arguments to consolidate white political power by expanding white women’s suffrage, see Crystal N. Feimster, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 199–200.

- Martha S. Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equity for All (New York: Basic Books, 2020); Mary Ellen Pethel, “Lift Every Female Voice: Education and Activism in Nashville’s African American Community, 1870–1940,” in Tennessee Women: Their Lives and Times, ed. Beverly Greene Bond and Sarah Wilkerson Freeman, vol. 2 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015), 239–269, 260; Elaine Weiss, The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote (New York: Viking, 2018), 187–188. On the limited concept of sisterhood, see Hazel Carby, “White Women Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood,” in Theories of Race and Racism: A Reader, ed. Les Back and John Solomos (New York: Routledge, 2009), 444–458.

- Feimster, Southern Horrors; Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Revolt Against Chivalry: Jessie Daniel Ames and the Women’s Campaign Against Lynching, rev. ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993).

- Benita Roth, Separate Roads to Feminism: Black, Chicana, and White Feminist Movements in America’s Second Wave (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 65–66.

- Judith Ezekial, Feminism in the Heartland (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2002), 1; Joanne Cook, “Here’s to You, Mrs. Robinson,” motive xxix, nos. 6 and 7 (March–April 1969): 5.

- Black Woman’s Manifesto, Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA) Archives, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, accessed July 1, 2020, https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/wlmpc_wlmms01009/.

- Jaime Harker, The Lesbian South: Southern Feminists, the Women in Print Movement, and the Queer Literary Canon (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 16; Julie R. Enszer, “Night Heron Press and Lesbian Print Culture in North Carolina, 1976–1983,” Southern Cultures 21, no. 2 (Summer 2015): 43–56; Grace Abels, “Mab Segrest on building a Southern movement for all,” Facing South, July 16, 2020, https://www.facingsouth.org/2020/07/mab-segrest-building-southern-freedom-movement-all.

- Great Speckled Bird 9, no. 2, March 1976.

- Cynthia Washington, “We Started from Different Ends of the Spectrum,” Southern Exposure 4, no. 4 (1977): 14–15.

- The synthetic accounts of the American women’s movement acknowledge the significance of the southern Civil Rights Movement but, with few exceptions, do not examine feminist activism in the South. For one example, see Ruth Rosen, The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America (New York: Penguin Books, 2006).

- Pauli Murray, “The Fourth Generation of Proud Shoes,” Southern Exposure (1977): 4–9; Anne Braden, “A Second Open Letter to White Women,” in “Generations: Women in the South,” special issue, Southern Exposure (1977): 50–53. See also Great Speckled Bird 1, no. 34, February 17, 1969.

- Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “Partial Truths,” Signs 14, no. 4 (Summer, 1989): 902–911; Jacquelyn Dowd Hall and Anne Firor Scott, “Women in the South,” in Interpreting Southern History: Historiographical Essays in Honor of Sanford W. Higginbotham, ed. John B. Boles and Evelyn T. Nolen (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1987), 454–509.

- Elizabeth Gillespie McRae, Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). On the backlash to feminism, see Marjorie J. Spruill, Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values that Polarized American Politics (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017).

- Alisha Haridasani Gupta, “Why Aren’t We All Talking about Breonna Taylor?,” New York Times, June 4, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/04/us/breonna-taylor-black-lives-matter-women.html; “Violence Against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2020,” Human Rights Campaign, accessed July 1, 2020, https://www.hrc.org/resources/violence-against-the-trans-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2020.

- Alysia Harris, “The South Hollers ‘Black Lives Matter,’” Scalawag, June 11, 2020, https://www.scalawagmagazine.org/2020/06/southern-small-protests-rural/; Malcolm Burnley, “Author Brittney Cooper on Harnessing Rage, Right Now,” New York Times, June 20, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/20/us/20IHW-black-lives-matter-protests-brittney-cooper-women.html.