"I don’t know whether people in [Bulgaria] realize how much they owe somebody they may never have heard of." —Elena Poptodorova

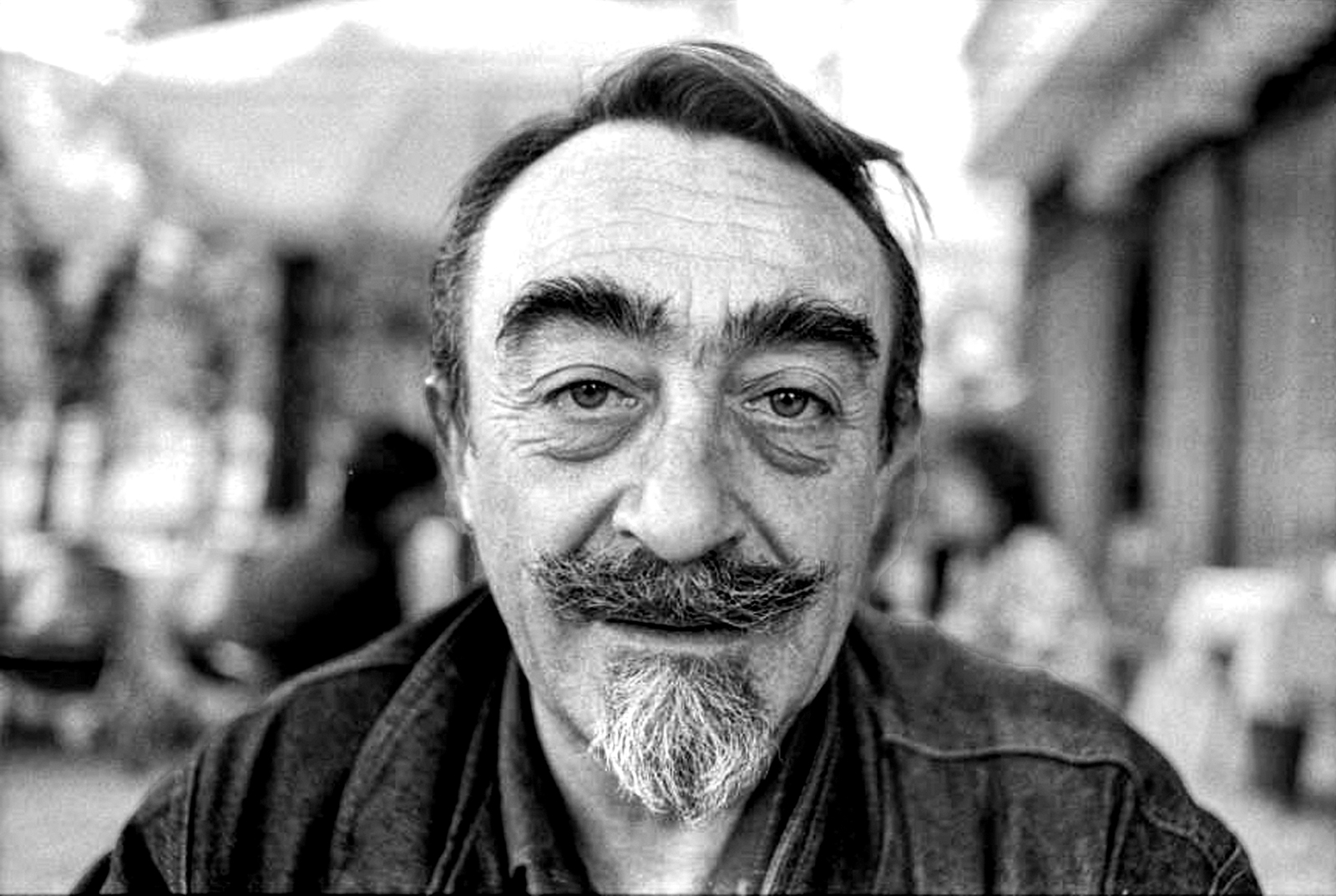

Without ever stepping foot on southern soil, renowned literary translator Krastan Dyankov made southern writing—its language, narratives, and nuances—come alive in his native Bulgarian. “The translator—not only of fiction, but of any text—is the Pony Express for the culture,” Dyankov said. “A great responsibility and a true knowledge of the matter you work with is required of a good translator.”

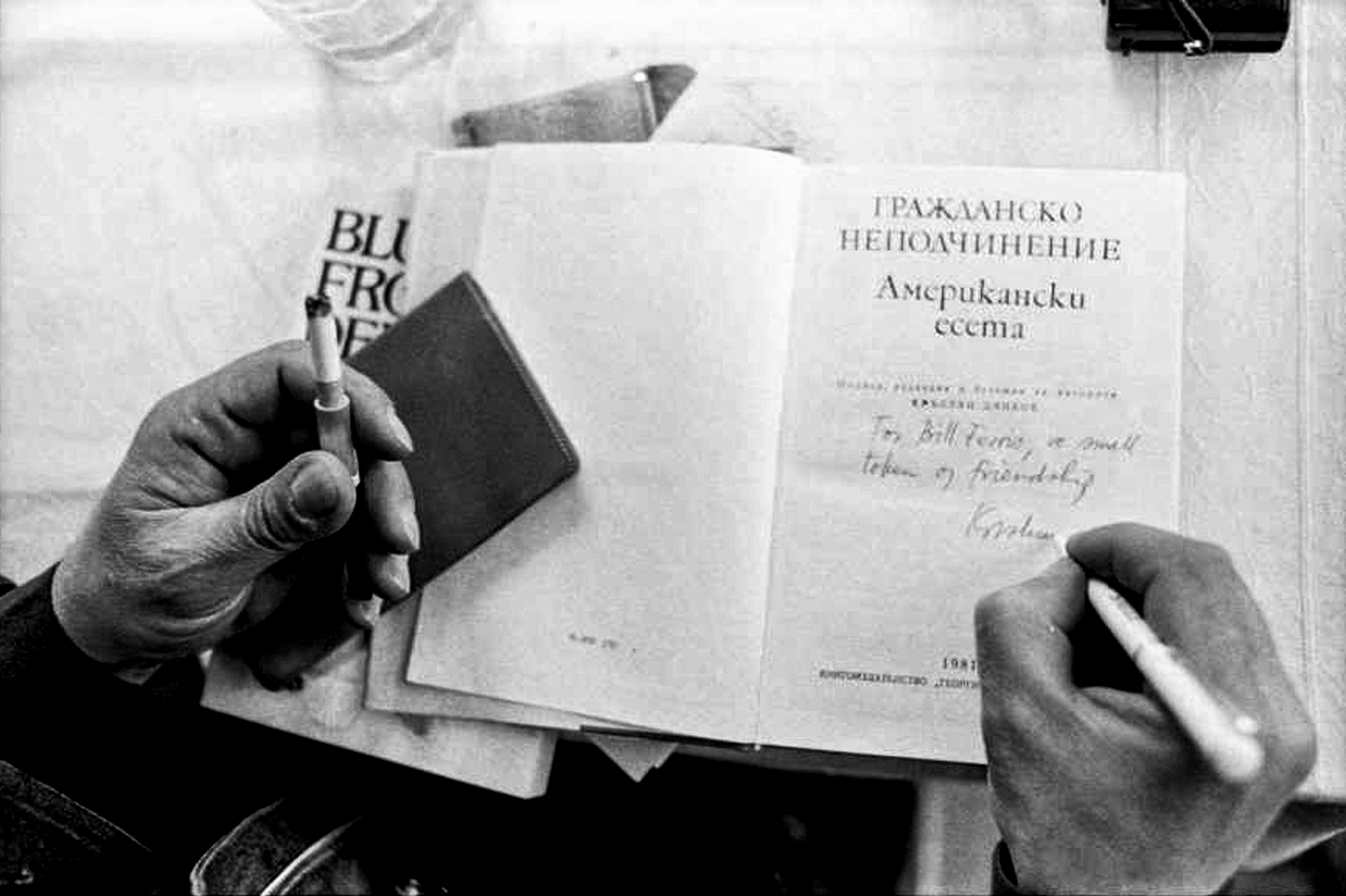

With our 21c Fiction Issue fresh off the press, we share a Loose Leaf interview with Bulgarian Ambassador (and literary translator) Elena Poptodorova on her mentor Dyankov and the power of words to forge cross-cultural understanding, as well as an excerpt from an interview with Dyankov conducted by William R. Ferris in 1987 from our Summer 2015 issue.

Language was probably the first thing I rationally realized and appreciated in life.

Elena Poptodorova, 2015

Elena Poptodorova is the current Ambassador of Bulgaria to the United States, and previously served in this role between 2002 and 2008. Ambassador Poptodorova holds degrees in English and Italian linguistic and literary studies from the Kliment Ohridski University of Sofia. After defending her thesis on Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, she was pulled in as a last-minute translator at Bulgaria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It turns out she had a knack for this work, and a forty-year career in international relations and politics was born. “I never quit learning and working with language,” she says. “I think words are probably the most important thing. I have deepest respect and admiration when they’re well-chosen, well-arranged.”

Ambassador Elena Poptodorova

Southern Cultures Interview, Summer 2015

This is what I think Krastan Dyankov was all about. He wouldn’t bother with time, in terms of deadlines. I don’t mean he wouldn’t observe a deadline, I mean he would take his time. So, a book may be translated, I don’t know, for a year, a couple of years. But he would not compromise for a more manufactured, industrial approach to translation. He would not compromise the quality. And he had the best knowledge of Bulgarian vernacular or dialects in order to render—which is never the same, but he got the closest anyone can, in translations from here. I don’t know whether people in this country realize how much they owe somebody they may never have heard of.

[Dyankov] introduced America to Bulgarians. He also started the Group of the Friends of America in Bulgaria, and that was well before ’89. And he was explaining America to Bulgarians without ever having set his foot here. He never visited; he never could visit.

I don’t know whether people in this country realize how much they owe somebody they may never have heard of.

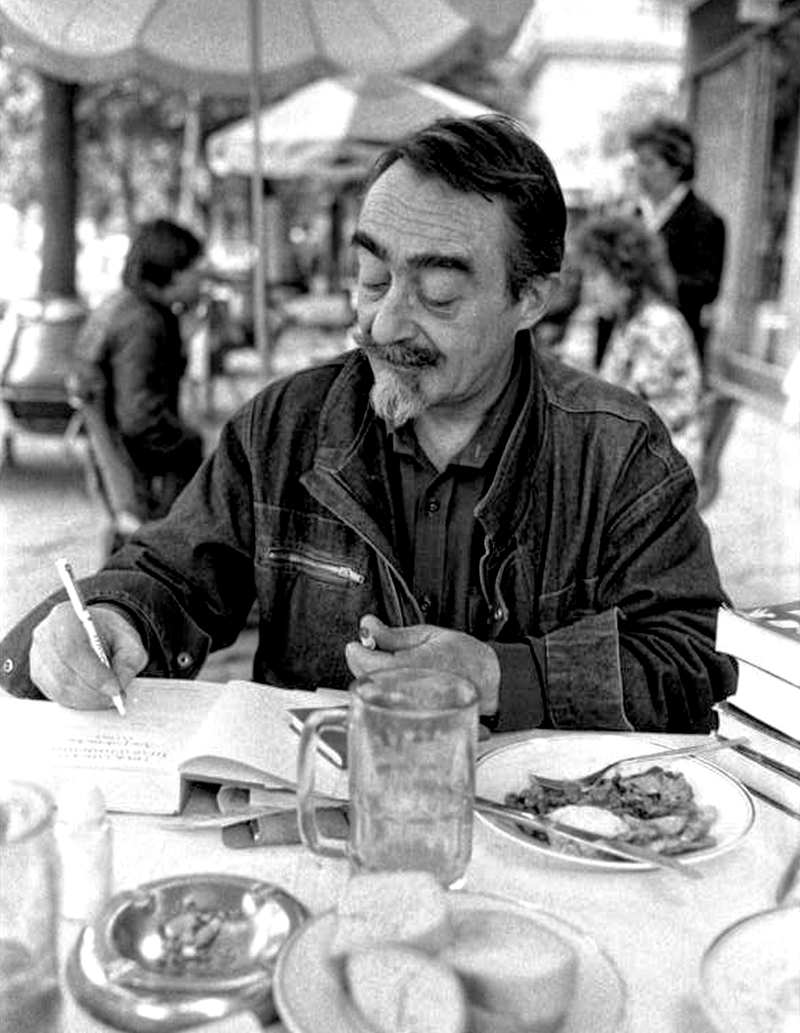

He was forbidden to travel for fear he may immigrate, and he was the most non-immigrant mind I know. He was so cozy, so comfortable, because there were the nice little pubs where they would sit together—I mean, that’s his own setting, he could never abandon that for trying to build up new networks. It’s—and especially in a divided world—it’s hard to do that. Today, it’s different. You have social media, you have too many different lines of communication. And in older times, what do you do? You find a nice cozy place, you sit together, you have a glass of wine, and you talk. You talk and talk and talk . . . He would never have sacrificed that. He would never have gone just cheap on that. But of course nobody thought of those things. So, anyway, he just wouldn’t travel.

He started translating Erksine Caldwell, and he wrote to him and somehow obviously the ledger went through. I don’t know exactly what happened, but Erskine Caldwell responded. He sent three books, which were autographed and dedicated to Krastan, which he never got. And he found out about those only years later when he found them in the library, the public library—but the dedication was there, so that’s how he found out that Caldwell responded. You cannot have that kind of a story today, you know.

This is what I meant by saying fair and unfair, fairness and unfairness. He was treated so unfairly in one way, by the establishment, by the system. And at the same time, you see, he does get the fair treatment, finally. So life—I believe that it always balances out, sometimes and someday.

Dyankov rendered the United States amazingly, precisely at the same time it was understood by the Bulgarians.

I think he’s the Bulgarian who knows this country the best to this very day, because he had his heart, his very fine tentacles—he felt everything. It was like reaching out, with the finest fibers you may have. So many Bulgarians live here, probably they don’t even know why. No, they know why, but they can’t appreciate the country in its entirety. And he rendered it amazingly.

Krastan Dyankov

Interviewed by William R. Ferris, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1987

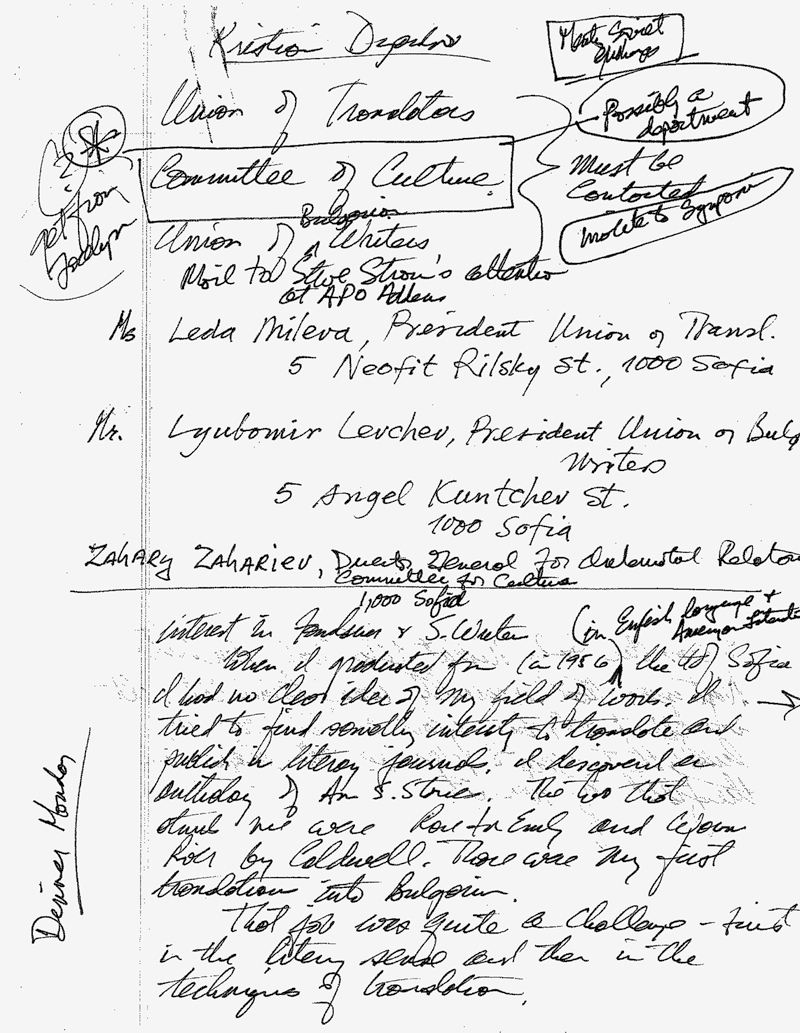

When I graduated in 1956 in English Language and American Literature from the University of Sofia, I had no clear idea of my field of work. I was the only student who took American literature. The next year that specialty was terminated. It was offered only one year, and it was my luck that year to receive the degree in the field of American literature.

I tried to find something interesting to translate and publish in literary journals. I discovered an anthology of short stories from the American South. The two that struck me were “A Rose for Emily,” by William Faulkner, and “Warm River,” by Erskine Caldwell. Those were my first translations into Bulgarian. That job was quite a challenge—first in the literary sense, and then in the techniques of translation.

I understood that the main issue is not the knowledge of a foreign language, but knowledge of your own language.

For the first time, I understood that the main issue is not the knowledge of a foreign language, but knowledge of your own language. The problems of a translator are usually of his own language. I have always been able to find the meaning of a foreign phrase linguistically, but if I could not find a Bulgarian equivalent bearing the spirit and atmosphere of the original, the job would not have been done well.

I developed a special interest in southern literature, and I moved from translation to literary scholarship. I decided to translate to make Bulgarians know more about a national literature—American literature—and American authors. It became a systematic work of presenting writers with their writing, either in single or several-volume editions.

I was attracted to Faulkner by his mystique and by his storyteller’s art. And then, of course, there was my interest in the Civil War of the United States. I was interested in the Civil War and what it brought to the South.

There were those two methods of seeing the South. One was Gone With the Wind, and the other was through Faulkner.

There were those two methods of seeing the South. One was Gone With the Wind, and the other was through Faulkner. I could gather more information about the Civil War from Faulkner than from history books. Through him, I understood the human condition of the time, which is perhaps the most interesting time in American history.

In translating Faulkner, I had to cope with a mountain of problems. I had to see his landscape, his Civil War battles, with my eyes. So I started collecting illustrations of the South. I found Mathew Brady’s photographs of the Civil War.

Something else also drew me to Faulkner—that many-layered story of his. I found I love that kind of storytelling. The big challenge for me as a translator was to get into Faulkner’s shoes and try to penetrate the different layers of his narrative.

When I started translating, only one Bulgarian had translated Faulkner. He is now over ninety and a very good friend of mine. Bodgan Anasov was the first to translate The Hamlet, and I was his editor. Then, when I translated the other two books of the trilogy, he was my editor.

When Anasov became too old to work, there was a young girl, Elena Khristova, whom I infected with the Faulkner fever. She translated a number of short stories and Sanctuary. Elena is now in Los Angeles working on her MA degree in American Literature at UCLA. Since she left Bulgaria, there is only me working on Faulkner. Last year, I decided to do a final tribute to him with a five-volume edition. The first publication will appear in 1992. The great problem is to find translators who can meet the challenge of translating Faulkner.