In 1986, singer Dobie Gray released From Where I Stand, an album identified as “country soul.” Because Gray, a Black man, had principally been marketed in pop and R&B, reviewers felt the need to address skepticism he might face about an entry into country music. “When they transition with Gray’s grace, then such moves should be applauded,” justified one music writer about the artist’s perceived shift from pop to country. But Gray was hardly a newcomer to the genre. He had recorded country songs since the 1960s and had attempted to break into the country music market since he moved to Nashville in the early 1970s, where he became an active member of the city’s music scene. “The country market is really important to Dobie because country music is important to him,” explained his producer, Mentor Williams, in 1974. “I don’t think that there would be a greater thrill for Dobie than to have a country smash.”1

Despite Gray’s efforts, he failed to gain commercial traction as a country artist and was still considered a genre outsider upon the release of From Where I Stand. As such, reviewers identified him as part of a long legacy of pop stars who have gone country. The same writer who applauded the singer’s grace also joked that “aging pop stars don’t die, they move to Nashville to record.” The summation refers to the age-old habit of mainstream stars dipping their toes into the world of country music. It’s a habit stretching back generations, and one that’s been revitalized in recent years as Beyoncé, Post Malone, and Lana Del Rey have entered their country music eras. Pop stars haven’t been the only artists to crossover. Country stars, from Dolly Parton to Taylor Swift, have also switched gears to pop, and countless country songs have made their way to the pop charts over the years. While such crossovers have been pervasive for generations, Gray’s experience reveals how racial double standards have often dictated which artists have been granted the ease to jump from pop to country.2

The marketing quandaries of Dobie Gray’s career show how marketing categories like country, R&B, and pop have often served as code for targeted demographics, rather than as strict sonic definitions. Country was invented as a marketing category in the 1920s under the labels of “hillbilly” and “old-time music”, and was first associated with a white, rural, and southern demographic. During the era of Jim Crow segregation, “race records” also emerged for Black consumers, despite the fact that Black fans and artists often enjoyed the same music as whites, and vice versa. These segregated marketing dynamics represent a key tension at the center of country music—its racial politics. Country music’s endurance as a commercial product is in part due to its continuous evolution, constantly taking from the mainstream, commonly in the form of Black music, from blues, jazz, rock ’n’ roll, and hip-hop, to remain palatable to modern listeners. Most often, these influences have been implemented once the sounds were no longer perceived as subversive or a product of youth culture. This is evident with the incorporation of hip-hop into country music over the past decade, well after that genre’s disruptive roots were heavily commercialized. Such sonic evolutions are also a symptom of the fact that country artists have grown up listening to mainstream genres as well as country. But while the addition of these sounds has been interpreted as innovative on the part of white country artists, Black artists have not been received the same. This tension has often manifested within the country and pop divide, where mainstream stars have been met with varying levels of skepticism upon entering the country music space based on race. After struggling for decades to find success in country music, Dobie Gray explained in 2000 that “[the music business] didn’t know where to place a black guy in country music (except) Charley Pride.” Within a decade, Darius Rucker would emerge as the only exception to that statement, as well as becoming the only Black pop artist to successfully transition to country with sustained popularity.3

The alliance between country and pop (a genre that features the most commercially successful and popular songs and artists) speaks to their mutual commercial interests. Country and pop often share audience demographics, seeking a broad swath of adult consumers that exists outside of cutting-edge pop music that has otherwise sought a younger demographic. Pop stars have found value in pivoting to country and its audiences once they’ve aged-out of the earlier phases of their careers. Country music has also frequently leaned on its adjacency to pop as proof of its legitimacy as an artistic and commercial product.

Although country and pop share close ties, the relationship between the two represents another tension that has forever sat at the heart of country music. Debates over authenticity have long plagued the genre, as fans and artists have cyclically argued and feared that a bond too close to pop could lead to a loss of identity in country music. Sociologist Richard A. Peterson has referred to this dichotomy as a constant battle between what he terms “hard-core” and “soft-shell” country music, speaking to the malleable identity that the genre has always carried. Hard-core country is associated with artists identified as traditional (the definitions for which have evolved over time), who often sing in a nasal style, whose concrete lyrics imply a direct lived experience, whose songs feature a fiddle, banjo, or dobro, and who wear clothing akin to rural or western wear. Soft-shell artists more closely resemble mainstream pop, with features like lush orchestral arrangements, unaccented vocals, and more polished or formal, attire.4

Despite the anxiety it’s induced, the link between country and pop has been key to country music’s enduring popularity and relevance. No other genre has existed, grown, and remained relevant in the commercial music marketplace more impressively than country music. Country’s relationship to pop has served as its most powerful commercial tool, used to broaden the country audience and boost radio airplay and record sales. It has also offered a mainstream endorsement to country music—equipped with middle-class respectability—and helped the genre overcome classism within the music industry and society at large for its roots and associations with a white, rural, and southern demographic. Over the past century, there have been several moments when country music’s relationship to pop, pop stars, and the greater mainstream has pushed the genre forward commercially. While these instances were often heralded as a potential death sentence for the genre, they have served instead as an accelerator.

“Everybody is Doing Country Music”

As a fledgling marketing category in the early 1920s, what came to be called country music did not yet have a firm identity. It would take decades for the genre and the business behind it to construct a historical legacy, equipped with key figures and institutional networks centralized in Nashville, including the Grand Ole Opry, the Country Music Association, and the Country Music Hall of Fame. No source would become more integral to establishing the genre’s historical mythology than the Opry—a radio program founded in 1925 that continues to run weekly and sell itself as “the show that made country music famous.” For as much as the Opry became a symbol of the genre’s historic and traditional roots, the early Opry also established itself as a model in the seesaw effect of hard-core versus soft-shell country aesthetics. It aired a variety of sounds, including artists like the Vagabonds, who were more in line with mainstream pop music, in addition to rustic old-time music along the likes of Opry star Uncle Jimmy Thompson.

During the 1930s and 1940s, cowboy songs dominated the mainstream as Americans found comfort in the likes of Gene Autry and Roy Rogers amid the Great Depression and World War II. One of the most popular songs of the era was “Don’t Fence Me In,” a cowboy song co-written by Cole Porter and recorded by countless stars, including Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald, and Frank Sinatra. Capitol Records, founded in Los Angeles in 1942, owed much of its early success to cowboy-themed songs. The second song ever recorded for the label was Ella Mae Morse’s “Cow-Cow Boogie,” which became Capitol’s first million-seller and a number one hit. Many of the era’s leading singing cowboys recorded for the label, including Tex Ritter and Jimmy Wakely, along with other country artists, such as Johnny Bond and Merle Travis. In 1949, Wakely gained crossover success when he scored a number one hit with “Slippin’ Around,” a duet with Margaret Whiting. In following years, Whiting continued to have sporadic success on the country charts and performed multiple times on the Grand Ole Opry.

By the late 1940s, major figures in the pop music industry looked to country music for material to record. The most notable figure to successfully bridge the country and pop divide in the post–World War II era was Mitch Miller, a highly influential recording industry executive. Miller’s first foray into country music occurred while working as a producer for Mercury Records in 1949, when he helped secure a pop hit with Eddy Howard’s recording of “Room Full of Roses,” a song first recorded by George Morgan. The following year, Patti Page had enormous success with her version of “Tennessee Waltz,” a recording that Billboard referred to in 1951 as “possibly the biggest song in the history of the modern pop song business.” Reports conflict on whether Miller had a hand in the recording, but it is clear the record’s success fueled future country-pop crossovers.5

When Miller was hired by Columbia Records in 1950, he continued to seek out country songs to record. Miller claimed he was first made aware of Hank Williams by Jerry Wexler, who was then a writer at Billboard. Upon hearing Williams’s “Cold, Cold Heart,” Miller pitched the song to Tony Bennett. The singer initially refused to record it, saying “I can’t do any of those cowboy songs,” but later agreed and scored a number one pop hit in 1951. That success pushed Miller to record more songs penned by Williams, including Frankie Laine’s version of “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” Laine’s duet with Jo Stafford of “Hey, Good Lookin’,” and Stafford’s own version of “Jambalaya.” Miller recorded these songs while fostering a relationship with Fred Rose and his son Wesley Rose, who oversaw the rights to Hank Williams’s songs through their publishing company, Acuff-Rose. The firm was established in 1942 by the elder Rose and Opry star Roy Acuff as the first publishing house to cater to country music. Their ownership of the Hank Williams songbook, and other significant hits, including “Tennessee Waltz,” offered undeniable proof of country music’s commercial viability and helped legitimize Nashville as the center of the country music business.6

Following Page, Miller’s successful roster of pop stars recording country songs proved a boon not only to record sales but also to country music’s legitimacy and acceptance in the mainstream. In the mid-1950s, the future of the genre appeared uncertain as the music business weathered a series of transformations, both cultural and technological. As rock ’n’ roll overtook popular culture, it energized a robust youth market for popular music, wedging a generational divide in both the culture and the marketplace. Format radio emerged as a strategy to cater to increasingly segmented pockets of the market such as these. Radio stations moved away from seeking large, broad audiences and began to foster specific demographics associated with particular genres of music. The Top 40 format played to teenagers with a heavy dose of rock ’n’ roll as it showcased leading hits. Other stations might cater to adult consumers by playing established pop stars like Frank Sinatra or Dean Martin.7

The all-country radio format faced a series of hurdles within this landscape but grew to capitalize on the alliance it had fostered in previous years with the adult-oriented mainstream pop music industry featuring the likes of Mitch Miller, Patti Page, and Tony Bennett. Miller was vocal in his distaste for rock ’n’ roll, while at the same time praising country music. Looking back on the moment when rock ’n’ roll emerged in the national spotlight, Miller later recalled that “country music, at that time . . . was the only honest music, from my point of view. Sure, there were some fine songs being written in rock & roll, but very few.” Miller’s support for country music was not standard practice at the time. Because the genre had first been created as “hillbilly music,” it remained associated with a poor white audience and, as such, remained a subject of classist discrimination within the music industry. One disc jockey in 1958 memorably lumped country music in with rock ’n’ roll as a “fad” genre that wouldn’t last: “Screening rock ’n’ rock tunes for my station is a very simple matter. First we keep a wastepaper basket handy and as the new releases come in, we just dump them in. We have the same screening technique for the so-called ‘modern jazz,’ hillbilly and other fad music—down the drain.”8

Members of the country music business worked diligently to improve their genre’s reputation. Artists campaigned to alter the name of the genre from “hillbilly” to folk music, and eventually settled on the name of country music to distance itself from its early associations. In 1958, the Country Music Association (CMA), a trade organization for members of the country music business, was founded in Nashville and no organization would do more to improve the genre’s reputation as a respectable, commercially viable product. The CMA commissioned market research studies to prove that their listeners were not poor and rural but rather part of the growing, socially mobile middle class of the post–World War II era. By 1963, an article in Music Reporter declared that “Hillbilly Music and the Hillbilly simply moved into a new era.” It claimed that the genre had assimilated and experienced social mobility in ways similar to other white ethnic minorities. “Hillbilly became the ‘old country,’ disowned like a successful immigrant’s homeland.”9

Pop artists like Patti Page and Tony Bennett had helped country music on its path towards respectability, and they would be far from the last to do so. But not all mainstream stars were eagerly welcomed in the same ways. When Ray Charles released Modern Sounds in Country & Western Music in 1962, the album was a massive success, quickly becoming the number one album on the Billboard chart, earning a Grammy Award, and spurring a successful follow-up, Vol. 2. Like Mitch Miller, Charles’s producer and A&R man, Sid Feller, reached out to Acuff-Rose Publishing to secure rights to record Hank Williams’s songs. But according to Hugh Cherry, an influential disc jockey at the time, Wesley Rose (who took over the company after his father’s death in 1954) was not initially amenable to the request. “Wesley Rose tried to stop it. [He] tried to buy the album to keep them from being released,” Cherry later claimed, adding: “he didn’t want black people. He didn’t want that identification.”10

Despite Rose’s protest, Charles received permission to record the songs, and to great success. Though the album was not played on country radio stations and Charles was not recognized as a country artist, his record was celebrated as evidence of the genre’s legitimacy within the mainstream. At marketing presentations, the Country Music Association eagerly showcased the album as proof of the genre’s widespread appeal and acceptance. Cherry later echoed such praise, calling the Charles album one of the “great boons to country music,” adding that they “took country music to an audience who had never been presented with it.”11

Ray Charles was not the only mainstream star to release a country album during this period. Other examples include Connie Francis, who released country albums in 1959 and 1962, and in 1964 put out a country duet album with Hank Williams Jr. In 1962, Kay Starr released Just Plain Country, and the following year Rosemary Clooney recorded Rosemary Clooney Sings Country Hits from the Heart and Dean Martin introduced Dean “Tex” Martin: Country Style in 1963. By 1966, Billboardsummarized the trend of pop stars going country, saying that “in previous years, only the great country songs made the pop music field. Now, everybody is doing country music.”12

As pop stars increasingly aligned themselves with country music throughout the 1950s and into the ’60s, country artists also veered into pop sounds as soft-shell country dominated with the rise of the Nashville Sound, led by producers Owen Bradley at Decca Records and Chet Atkins at RCA. Artists like Patsy Cline and Ray Price, who previously would have been identified as hard-core, became models of the new sub-genre. Price’s sound switched gears from the signature “Ray Price shuffle,” equipped with twin fiddles and pedal steel guitar, as heard on songs like “Crazy Arms,” to lush orchestral arrangements and background singers on songs like “Make the World Go Away.” Cline traded in her cowgirl fringe for elegant cocktail attire and played Carnegie Hall with the Grand Ole Opry in 1961. The New York Times noted how the “program was representative of the two chief currents in country music, the traditional and the popular,” identifying Patsy Cline as a “modern popular singer.”13

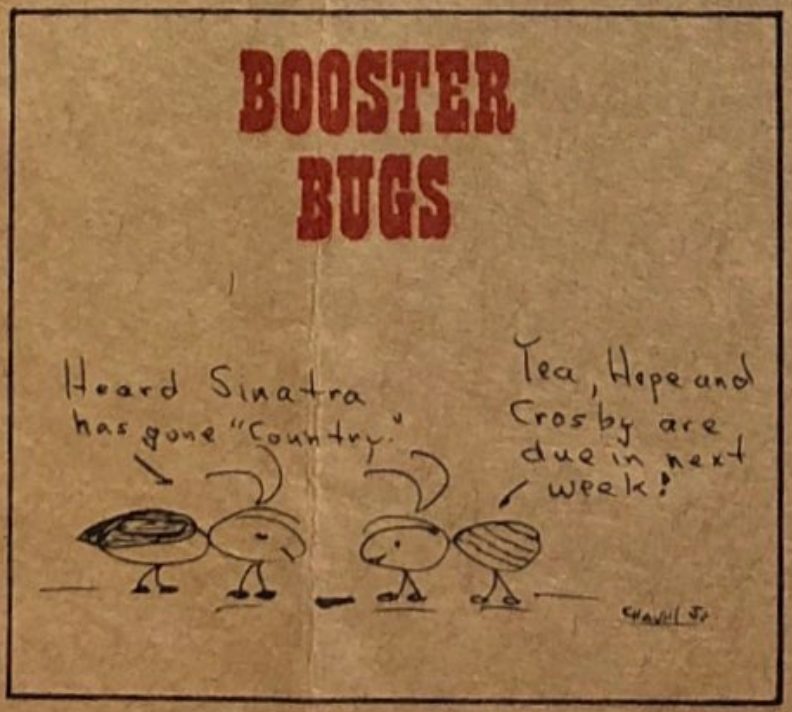

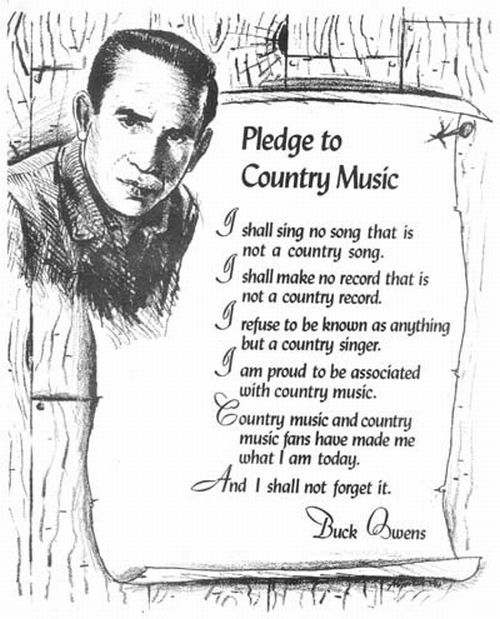

By the mid-1960s, the dominance of the Nashville Sound created a backlash among fans who claimed country music had strayed too far into the world of pop. “As far as I’m concerned, there is only ONE Country Music man left in the field. And that’s Roy Acuff. Now there’s Country entertainment. Not Rock ’n’ Roll or Pop. Just plain Country Music. I only hope he never gets caught in this Pop Rut,” a fan wrote in a letter to Music City News in 1964. Other fans in the same column pointed to the inconsistency with which country artists were bemoaned for “going pop.” As one wrote, “Take Ray Price’s case since he has been the target of this heated discussion, though I haven’t figured out why there haven’t been complaints about Jim Reeves, Skeeter Davis, etc., whose records have been ‘more pop’ and for longer than Ray’s.” Such fans not only targeted country artists for going pop but also rock ’n’ roll. In California, where hard-core country music in the form of the Bakersfield Sound reigned, Buck Owens went so far as to issue his “Pledge to Country Music,” which he published in various outlets, including Music City Newsand Country Music Review. The statement vowed various loyalties to the genre, saying: “I shall sing no song that is not a country song,” and “I refuse to be known as anything but a country singer.” When Owens released a Chuck Berry cover on his next album, however, he faced backlash from fans who claimed he’d failed his promises by falling into rock ’n’ roll.14

“I Appeal to Middle America, Not Just Country”

In 1966, rock ’n’ roll outsold adult-oriented pop music for the first time, reflecting rock’s dominant role in the popular music marketplace, and its position as the soundtrack of the counterculture. The country music business capitalized on the gap created by the decline in the adult-oriented pop music that reigned in previous years. The alliance between consumers of country music and mainstream pop were also emboldened by the fading rural roots of the core country consumer. “Our songs don’t necessarily apply to people just in the country, because there are very few people who live in the country on farms anymore,” Owen Bradley said in 1969. The success of stars like Ray Charles and Tony Bennett doing country songs had also expanded the idea of the imagined country music consumer, resulting in an audience that had grown beyond the formerly rural white southerner to include broad swaths of the mainstream. “I don’t consider myself strictly a country artist,” asserted Eddy Arnold in 1972. “I appeal to middle America, not just country. I choose my songs the same way Perry Como or Sinatra would. I look for a good lyric and a good melody.” Como also released a country album in 1965, The Scene Changes, which was recorded and produced by Chet Atkins in Nashville. Arnold and Como were evidence of the joint audience that country and the mainstream shared.15

The country music business further legitimized itself with the introduction of the Country Music Association (CMA) Awards in 1967, which were televised nationally for the first time the following year. The awards are similar to the Oscars in that they are determined by voting members of their industry’s leading trade organization. In the case of the CMAs, awards are determined by voting members of the CMA, a trade organization for members of the country music business. Since its founding, the show has served as a state of the field for country music (albeit an incomplete one) and acts as the genre’s biggest PR event of the year, when a large audience—country music fans and others—can tune in during primetime to see what’s going on. The show has also acted as one of the most prominent stages, where the bridge between country music and pop has been in harmony and in tension.

The broad appeal of country music grew increasingly evident in the early 1970s. In 1974, country music historian Bill Malone summarized the popularity of the genre, saying: “Country music, once an embarrassment to people who liked it in spite of themselves, has become ‘country chic’ . . . It’s the thing nowadays for people to dress in country clothing and play the role.” The year prior, a Newsweek cover featuring Loretta Lynn reported on a “Country Music Craze” that had overtaken the nation. The same year, New York City introduced its first all-country radio station, WHN. A news release put out by the CMA celebrated the occasion, declaring: “A long awaited dream comes true for the Country Music Association and for many Country Music fans with the format change of WHN Radio in New York City.” Over the next few years, the station would go on to gain the largest country music audience in the country.16

Country music’s commercial dominance was visible through a growing number of country-pop crossovers throughout the 1970s. One of the most successful country artists in this vein was Charlie Rich, who was a bit of an aging star himself before finding success in country music. Celebrated as a “white Ray Charles” for his talents as a singer, songwriter, and pianist, he had struggled for years, recording between Memphis and Nashville and jumping from one record label to the next. His luck changed when he teamed up with producer Billy Sherrill at Epic Records in the late 1960s. The two first met in the mid-50s when Rich recorded for Sun Records, where Sherrill worked as an engineer. Like the generation of Nashville producers before him, Sherrill found success at Epic by pushing the sounds of country music forward. “I don’t care if it is George Jones,” Sherrill explained. “I don’t want it to sound too country.” What resulted was “countrypolitan,” country music with lush, pop-friendly orchestral arrangements and heavy doses of pedal steel mixed in, with which artists like Tammy Wynette, George Jones, and Tanya Tucker had success. In 1973, Sherrill and Rich had their first massive hit when “Behind Closed Doors” reached number fifteen on the pop charts, quickly followed by “The Most Beautiful Girl,” which hit the top spot on both the pop and country charts. With Rich, Sherrill mastered a sound that drew from the singer’s earlier stints in rock ’n’ roll and rhythm & blues. Rich’s manager explained that the singer was making country music “accessible to more people, taking it away from hay bales and that cornball stuff. Giving it some class.”17

Rich’s groundbreaking success pushed him firmly into the mainstream, landing him bookings that included a show at the Hilton in Las Vegas. Additional rotating acts at the venue included Liberace, Barbara Streisand, and Ann Margaret, alongside other country stars like Johnny Cash, Glen Campbell, and Charley Pride. Such performers targeted mainstream, adult consumers with disposable incomes. One artist who shared a billing with Rich was the Australian pop star Olivia Newton-John, who joined his show after having her own unexpected success on the country music charts in 1973 with her song “Let Me Be There.” Newton-John entered the country music space with little knowledge of the genre. “I enjoy country music . . . but I don’t know much about it,” she said. “Some country music is just too heavy for me. But I like the soft stuff, like Charlie Rich.”18

The country music and pop alliance reached a breaking point in 1974 when Newton-John, torpedoed by “Let Me Be There” and radio airplay on stations like WHN, received the CMA award for the Top Female Vocalist of the Year. Some members of the country music industry in Nashville defended the award. “That’s democracy,” said Jo Walker, executive director of the CMA, referring to the voting process of CMA members who had secured Newton-John’s win. Bill Williams, Nashville’s Billboard editor, explained that the award foreshadowed a “wave of the future and a sure sign that country music is alive and growing and unwilling to stagnate.” Not everyone in Nashville was as celebratory. “We don’t want somebody out of another field coming in and taking away what we’ve worked so hard for all year,” said Johnny Paycheck.19

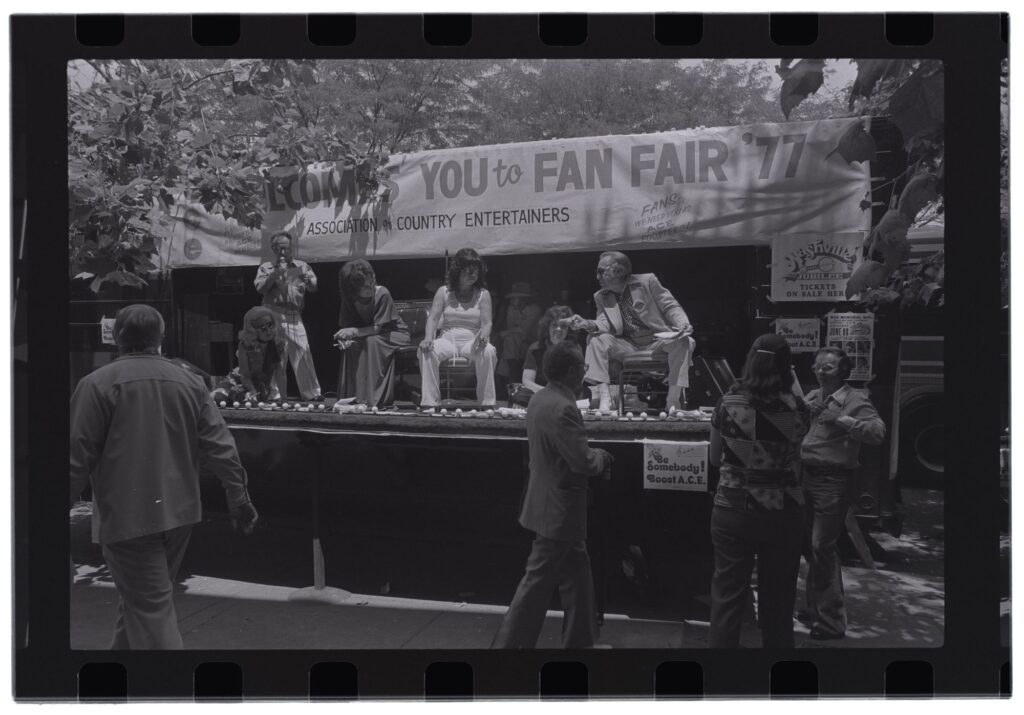

While Paycheck’s remarks could be interpreted as bitter, his sentiments were validated by several peers who felt the need to create protections for their livelihoods as country artists working to maintain careers in Nashville. Within weeks, a meeting was called at the home of George Jones and Tammy Wynette to discuss the changing landscape country artists faced. As a result, a group of approximately fifty country artists, including the likes of Paycheck, Johnny Cash, and Merle Haggard, agreed to form a new organization, the Association of Country Entertainers (ACE). An attorney speaking on behalf of the group explained that it would be limited to those who “basically make their living in country music as a country entertainer.” This differentiated the group from the CMA, which worked to serve any individual making their living in country music, be it as an artist, publisher, promoter, disc jockey, and so on.20

ACE members’ efforts were further validated at the CMA Awards the following year, in 1975, when John Denver, another mainstream star who did not identify principally as a country artist, received the biggest award of the night for Entertainer of the Year. Tensions were inflamed further when Charlie Rich introduced the award and proceeded to light the envelope on fire on national television. Though Rich claimed to be under the influence of painkillers, his actions were nevertheless interpreted to be directed at Denver’s win.

Members of ACE remained adamant that they carried no ill will towards the CMA but felt the need to support one another as self-affirmed country artists. “We’re not a bunch of rabble-rousers trying to burn down the Country Music Association and the [Country Music] Hall of Fame,” contended ACE chairman Bill Anderson. “Our association is not interested in labeling,” he continued. “We’re more interested in whether an artist says he or she is country or not.” Anderson later recalled that they had established ACE because “we decided we needed to be closer as a group and have some picnics and parties during the year,” and that “there was some talk about our trying to start a retirement home for country entertainers.” Other ACE newsletters, however, hinted at infighting that seemed to suggest a sense of animosity toward the CMA. The group’s motto was defined as “preserving, promoting and perpetuating true Country Music”— a clear play on the founding goals of the Country Music Association. Early advertisements for the CMA described it with the “purpose of fostering, publicizing and promoting the growth of and interest in country music.”21

Over the next few years, ACE worked to define its grievances within the country music business, but also became a target of criticism itself, accused of overlooking the sonic innovation that had long pushed the genre forward. An article in Country Music magazine touched on all the confusion of the moment. “The reason it’s complicated is because country music, if there is any such thing, has been changing ever since it was invented. Crossover is not a new thing,” it reported, explaining that the effort to “‘keep it country’ is practically meaningless.” Nashville’s Billboard editor Bill Williams argued the success of the CMA, and country music more broadly, was due to its broad embrace of sounds, claiming blues-driven Jimmie Rodgers and jazz-inspired Bob Wills under the umbrella of country music by voting them in to the Country Music Hall of Fame. “It has all these sounds, which only makes it richer,” he explained. “Now, the fact that John Denver or the Eagles or Poco or some of these so-called country rock groups are singing country only expands its general audience and makes it more powerful than it was before.” Such a broad range of artists became a growing target for ACE, who attacked radio stations that were incorporating so many new artists. In a newsletter titled “ACE Asks CMA ‘Is WHN Country?’,” the group called out New York City–based WHN and other radio stations for featuring too broad an assortment of music on their playlists.22

Although WHN faced pushback from the likes of ACE, it was developing a commercial strategy that captured a broader audience for country music, just as Williams had explained. A 1978 article in Billboard described how the country music format was capitalizing on the void left by the decline of middle-of-the-road (MOR) pop artists. It described how artists like Conway Twitty and Frank Sinatra “have the same listeners—adults aged 25 to 49.” Twitty, like Charlie Rich, began his career as a rock ’n’ roller in the 1950s, later turning to country music once he’d aged out of the initial phases of his career. The Billboard article explained how “the recording demise in the early ’70s of adult-oriented artists such as Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Ed Ames, Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme, etc., set the dial for the radio ascendancy of today’s country artists.” Ed Salamon, program director at WHN, further elaborated that “Country has taken the place vacated by true MOR music . . . During the ’60s, there existed music made strictly for adults, without any pretense toward mass appeal to include teenagers . . . Then labels began dropping those artists when they quit having hits.” The article went on to explain Salamon’s strategic reasoning at WHN, highlighting how “radio stations wishing to reach a pure adult audience—the most attractive to potential advertisers—faced several alternatives: heavy personality, information, all-talk or country music.”23

The relationship between country and pop throughout the 1970s resulted in the greatest levels of commercial success experienced by the country music industry up until that point—and, as a result, its greatest identity crisis—but this would hardly be the last time these dynamics would erupt in country music. By the end of the ’70s, a new craze and ensuing upheaval occurred when the Urban Cowboy boom reached its pinnacle around the election of Ronald Reagan in late 1980 and Barbara Mandrell scored a number one country hit with the anthem “I Was Country When Country Wasn’t Cool.” It was at the peak of this fad that ACE disbanded in 1981. Country music would experience its greatest existential crisis yet by the mid-80s, when news outlets surmised that the genre appeared dead following the fall of Urban Cowboy. By the early 1990s, with the breakthrough of artists like superstar Garth Brooks, country music would again experience its greatest surge amid claims that the genre was the new pop music, marking yet another period of boom and bust for the country music industry. Alan Jackson’s 1994 chart-topper “Gone Country” again spoke to a moment when large numbers of newcomers flocked to the genre.

In the modern era, ripples from previous moments of the country/pop crisis continue to remain influential within the country music business. Though Ed Salamon received heavy criticism for his diverse playlists as a country radio programmer in the 1970s, he would remain a highly influential figure in this space, moving to Nashville in 2002 when he became the executive director of the Country Radio Broadcasters. And while ACE was a short-lived organization, its major pleas appear to have influenced future voting patterns at the CMAs, given that no major star who has not principally identified as a country artist has won major awards at the show in the contemporary era.

“They Don’t Just Listen to Country”

Over the past decade, the CMA Awards have remained a space where the country and pop relationship is highly visible, and where it’s existed in both unity and conflict. In recent years, Katy Perry, Jennifer Hudson, Charlie Puth, Pink, Beyoncé, and Justin Timberlake have all performed on the show. Timberlake joined in 2015 as part of duet appearance with emerging artist Chris Stapleton. Host Brad Paisley introduced the performance as “The Nashville sound meets the soul of Memphis,” and the two performed soul-influenced versions of Timberlake’s song “Drink You Away,” along with “Tennessee Whiskey,” with which Stapleton would have massive success. The performance became significant not only for its strong reception, but in the days following, hopes swirled that Timberlake might make the switch to country. While the former NSYNC star didn’t choose to embrace the genre further, his visit nevertheless marked a key moment when Stapleton became one of the biggest names in the genre, going on to win more than a dozen CMA awards in less than a decade since. Though Stapleton has often been celebrated for being a model of authenticity in country music, his vocals and music heavily draws from soul and R&B music.24

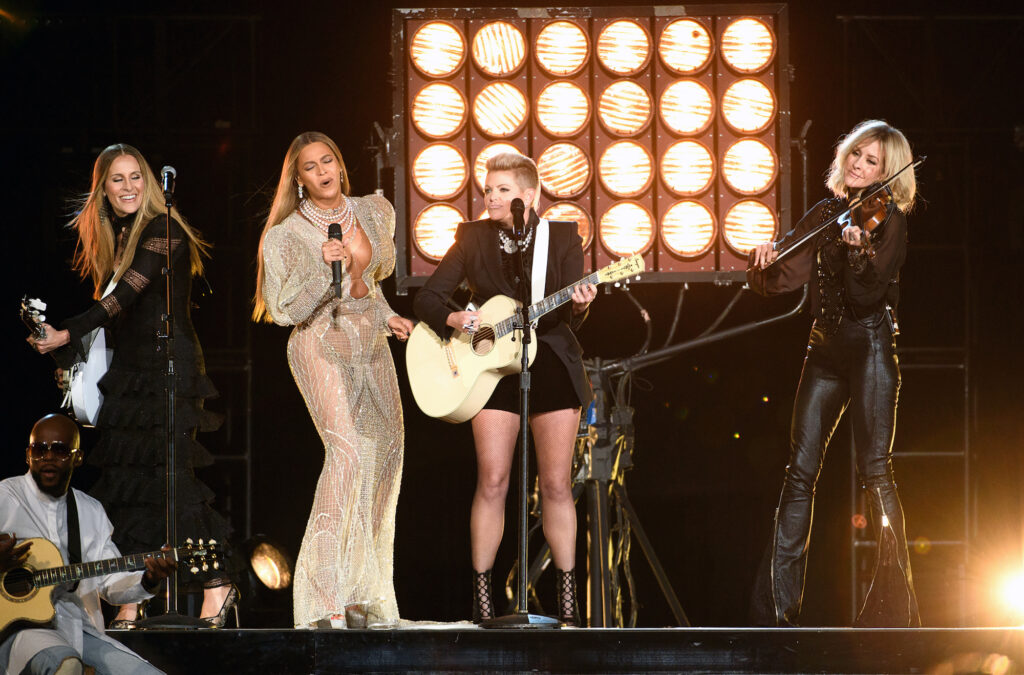

The year after Timberlake and Stapleton performed, Beyoncé appeared on the CMAs alongside The Chicks (formerly known as The Dixie Chicks). Unlike the highly acclaimed pop/country crossover of the previous year, The Chicks’s performance of Beyoncé’s “Daddy Lessons” was met with fierce resistance from fans, who attacked the artists’ political beliefs (the Chicks had been ostracized from country music after lead singer Natalie Maines spoke out against the Iraq War in 2004), widely criticized the song for not being country, and sometimes vocalized openly racist and sexist remarks about the stars.25

With the release of Cowboy Carter in 2024, fans and critics again brought up Beyoncé’s possible appearance at the CMAs as evidence of racial double standards that continue to be endemic to the country music industry, where white artists are celebrated for their incorporation of Black music and Black artists are met with skepticism. The singer took to her Instagram to explain that “this album was five years in the making,” and in a reference widely perceived to be about her CMA performance, explained that the record was “born out of an experience that I had years ago where I did not feel welcomed.” She went further, saying, it “ain’t a Country album. This is a ‘Beyoncé’ album.” Despite such a claim, and after some backlash from her fans, country radio stations began playing her lead single off the record, “Texas Hold ’Em,” which reached number one on the country charts. One radio programmer rationalized why the song made sense on country stations, saying “the core country audience is still that 35-to-45-year-old soccer mom, and they don’t just listen to country, they listen to pop, where Beyoncé has a huge impact.” The airplay was not enough for the singer to be nominated for CMAs, however, given that she did not record the album in Nashville. Beyoncé is also not fully representative of the aging-pop-star-going-country paradigm, considering her level of stardom and having just come off a massively successful previous album and tour. Her promotional efforts behind Cowboy Carter suggest she had no interest or need in getting affirmation from the CMAs. Like Charles’s Modern Sounds in 1962, Beyoncé’s latest is representative of how a significant country-influenced album can exist outside of the country music industry, while still benefiting its bottom line through promotion of the genre.26

Within months of Cowboy Carter’s release, Post Malone, a white artist who first achieved stardom as a rapper, also released a country album, F-1 Trillion. Post follows the long trajectory of declining pop stars who have gone country, and in more recent history accompanies fellow white rappers, including Kid Rock and Jelly Roll, who have switched to the genre. His popularity peaked after his song “White Iverson” took off in 2015. In recent years, his success has faltered, and his last album was his first to not include a top ten hit. With a transition to country, Post has revitalized his career, returning to the top of the charts with “I Had Some Help,” a duet with Morgan Wallen, the biggest star in country music and another artist heavily influenced by hip-hop. He has done so while offering full deference to Nashville and the country music industry. “He came [to Nashville] and baptized himself in the culture and the community,” said ERNEST, a leading country artist with whom Post recorded a duet for F-1 Trillion. The approach has paid off, granting him praise and endorsements from across Nashville. As a double album, F-1 Trillion features more than a dozen duets with country stars of the past and present, revealing how thoroughly the singer has ingratiated himself into the country music industry. During his first year in country music, he received four CMA award nominations and an invitation to make his debut performance on the Grand Ole Opry—two key markers of his embrace within the industry. The recent trajectory of his career is but one example of how the long trend of aging pop stars going country remains alive and well. Post’s successful pivot to country reveals the symbiotic relationship pop and country continue to share, where both parties stand to gain commercially. While he has not physically moved to Nashville, he has symbolically relocated there, capturing the attention of the country music business and being heralded within Nashville as evidence of country music’s ongoing relevance and mainstream popularity.27

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Amanda Marie Martínez is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of American Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her work has also appeared in the Journal of Popular Music Studies, California History, NPR, and the Los Angeles Times. Her book project, Gone Country: How Nashville Transformed a Music Genre Into a Lifestyle Brand, is under contract with UNC Press.

NOTES

- Robert K. Oermann, “Dobie Gray’s New Style Lauded as ‘Country Soul’,” The Tennessean, June 21, 1986, 1-D; Lee Rector, “Dobie Gray Drifts Into Solid Country,” Music City News, January 1974, 14, 31.

- Edward Morris and Michael McCall, “Album Review: Vinyl Conflict,” Music Row, May 1986, 14.

- Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Fabricating Authenticity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010); Bill Ellis, “Get Lost in the Rock and Roll of ‘Drift Away’ Dobie Gray,” The Commercial Appeal, July 29, 2000, F3. Several mainstream Black artists have found success recording country songs, having their songs recorded by country artists, and recording duets with country artists. Most often, these interactions have been fleeting or the artists have been positioned as outsiders to the genre. Examples include Louis Armstrong (who recorded a song with Jimmie Rodgers in 1930, and who also recorded his own country album in 1970), Ray Charles, Nat King Cole, Tina Turner, the Pointer Sisters, Lionel Richie, Aaron Neville, and Nelly, among many others. Rucker remains the only former pop star to have sustained success on the country music charts and who has principally been identified as a country artist.

- Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity (University of Chicago Press, 1997), 137–155.

- No author, “‘Tenn.’ Disks, Sheets Top All Modern Pop $$,” Billboard, May 19, 1951, 1; James M. Manheim, “B-Side Sentimentalizer: ‘Tennessee Waltz’ in the History of Popular Music, The Musical Quarterly 76, no. 3 (Autumn 1992): 346.

- Mitch Miller Interview, by John Rumble, February 24, 1983, 5. Country Music Hall of Fame Archives.

- Susan J. Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 219–255.

- Mitch Miller Interview, by John Rumble, February 24, 1983, 11. Country Music Hall of Fame Archives; Jeffrey J. Lange, Smile When You Call Me Hillbilly: Country Music’s Struggle for Respectability, 1939–1954 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004); “After-Hours Session,” Billboard, February 24, 1958, 9.

- Charles Hughes, “Country Music and the Recording Industry,” in The Oxford Handbook of Country Music, ed. Travis D. Stimeling (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 205; Peterson, 185–201; Diane Pecknold, The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007); Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999); David R. Roediger, Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants became White. The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs (New York, Basic Books,2005); Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 2009); No author, “Hillbillies Never Die,” Music Reporter, November 2, 1963, 63.

- Hugh Cherry Interview, by John Rumble, February 29, 1996, 38. Country Music Hall of Fame Archives.

- Diane Pecknold, “Making Country Modern: The Legacy of Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music,” in Hidden in the Mix: The Black Presence in Country Music, ed. Diane Pecknold (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 82–99; Hugh Cherry Interview, by John Rumble, February 29, 1996, 37. Country Music Hall of Fame Archives.

- Jocelyn R. Neal, Country Music: A Cultural and Stylistic History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 186; No author, “It Pays to Think Country,” Billboard: The World of Country Music, Section 2–October 29, 1966, 102.

- Robert Shelton, “‘The Grand Ole Opry’ is Heard in a Program of Country Music,” New York Times, November 30, 1961, 41.

- “Letters to the Editors, ” Music City News, December 1964, 2; Full page “Pledge to Country Music” ad, Music City News, March 1965, 5.

- Keir Keightley, “Music for Middlebrows: Defining the Easy Listening Era, 1946–1966,” American Music 26, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 309; No author, “An Interview with Owen Bradley,” Country Song Roundup 21, no. 114 (January 1969): 45; No author, “Can’t be to [sic] Country for Vegas Audiences,” Country Music Booking Guide, October 21, 1972, Section II, 4.

- John Parris, “Country Music Has Become Respectable,” Asheville Citizen-Times, September 1, 1974, 4A; “The Country Music Craze,” Newsweek, June 18, 1973; No author, “New Release: A Dream Come True,” Country Music Association Clippings File, Country Music Hall of Fame and Archives.

- Bill Williams, “Rosenberg: ‘There Was Never Any Question About What the Man’s Capabilities Were’…,” Billboard, September 14, 1974, CR-16; John Morthland, “Changing Methods, Changing Sounds: An Overview,” Journal of Country Music12, no. 2 (1989): 6; J. R. Young, “Olivia Newton-John, Country Singer. What?” Country Music magazine, December 1974, 58.

- Ibid., 62–63.

- B. Drummond Ayres Jr., “‘Crossovers’ to Country Music Rouse Nashville,” New York Times, December 1, 1974, 75.

- Jerry Bailey, “Artists Organize New Group, Want Country to Stay ‘Country’,” The Tennessean, November 13, 1974, 1.

- Jerry Bailey, “Country Music Group Defended,” The Tennessean, November 15, 1974, 22; Bill Anderson with Peter Cooper, Whisperin’ Bill Anderson: An Unprecedented Life in Country Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016), 177; No author, “Welcome,” Booster Banner: Association of Country Entertainers, Volume 1, Number 1, Fan Fair Issue, June 1976, 1. Grand Ole Opry Archives, ACE file; “Country Music Association, INC. Membership Application,” Billboard, December 15, 1962, 38.

- Martha Hume, “What the Hell Is Happening to Our Music?” Country Music magazine, February 1976, 28, 30; Jerry Bailey, “ACE Attempts to Resolve an Old Problem,” Country Music magazine, March 1975, 16; No author, “ACE Asks CMA ‘Is WHN Country?’,” Statement Prepared By: The Association of Country Entertainers Information Services/Communications Office, January 24, 1977. ACE Opry File, Grand Ole Opry Archives.

- Ray Herbeck Jr., “Country Formats Find Place Amid MOR Vacuum,” Billboard’s World of Country Music, October 21, 1978, 32.

- Mikael Wood, “CMA Awards 2015: Justin Timberlake and Chris Stapleton are a Killer Team,” Los Angeles Times, November 5, 2015; Jocelyn Neal, “‘Tennessee Whiskey’ and the Politics of Harmony,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 32, no. 2 (June 2020): 214–237.

- Joe Coscarelli, “Beyoncé’s C.M.A. Awards Performance Becomes the Target of Backlash,” New York Times, November 3, 2016.

- Steven J. Horowitz, “Beyoncé Reveals That ‘Act 2: Cowboy Carter’ Came About After Experience ‘Where I Did Not Feel Welcomed,’” Variety, March 19, 2024; Chris Willman, “The Country Format Is Bullish on Beyoncé’s ‘Texas Hold ’Em,’ Top Radio Execs Say,” Variety, February 15, 2024.

- Joe Coscarelli, “How Post Malone Went Country (Carefully, With a Beer in His Hand),” New York Times, August 8, 2024.