“‘No, I don’t want my picter took. / Gwine all round in de paper and de book—/ Ever-body knowin’ des how I look.’”

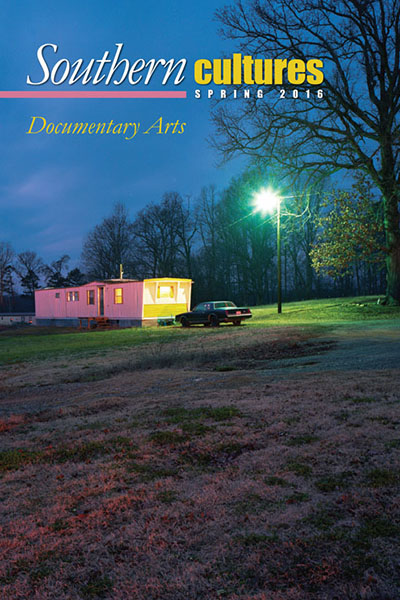

Hale County, Alabama. For many, the words conjure images of Allie Mae Burroughs’s face. Appearing older than her twenty- seven years, she stands before an unpainted clapboard house staring straight into Walker Evans’s lens, her lips pursed and brow furrowed. Others may see a kudzu-covered country store embalmed by William Christenberry’s lush Kodachrome film. Some might hear in their heads James Agee’s often quoted archaeological list of materials he wanted to present to readers instead of words in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: “If I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech . . .” For others, Hale County summons images of the Rural Studio, an innovative architectural project Samuel Mockbee started there in the early 1990s. The photographs by the Rural Studio’s photographer, Timothy Hursley, vividly depict the striking designs of houses, chapels, and community centers made of salvaged tires, hay bales, license plates, and innumerable reusable materials. A writer who visited Hale County in 2005 for a story on the Rural Studio described its landscape as if it was a gallery displaying the work of these documentary artists: “Drive through Hale County today, and Agee and Evans’ world will come to life. Broken-down pickup trucks and dusty storefronts are evidence of residents’ hardscrabble lives, eking out a living on catfish ponds and in cotton fields, in endless battles against the kudzu. Look out the car window at a freshly plowed acreage, and you’ll see Christenberry’s Rothko-like bands of brown, green and yellow glistening in the afternoon sun.”