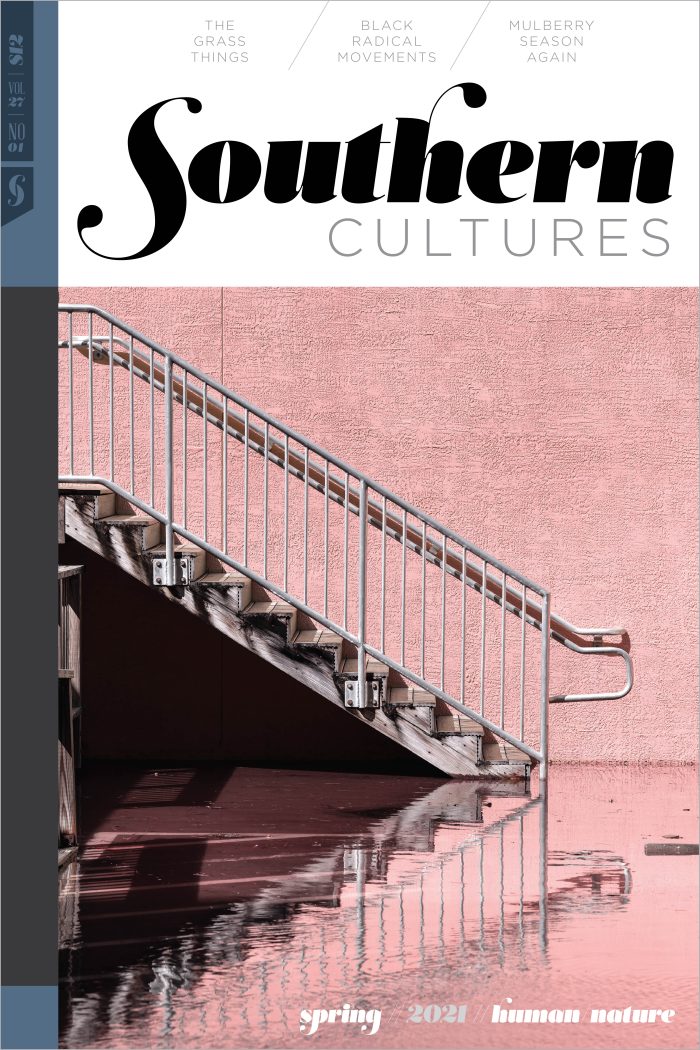

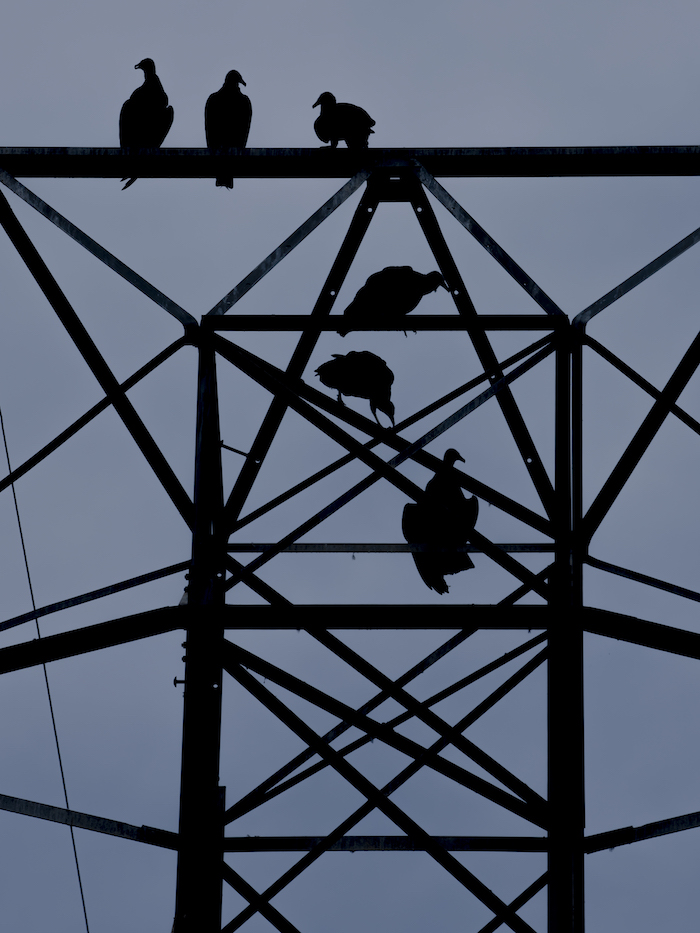

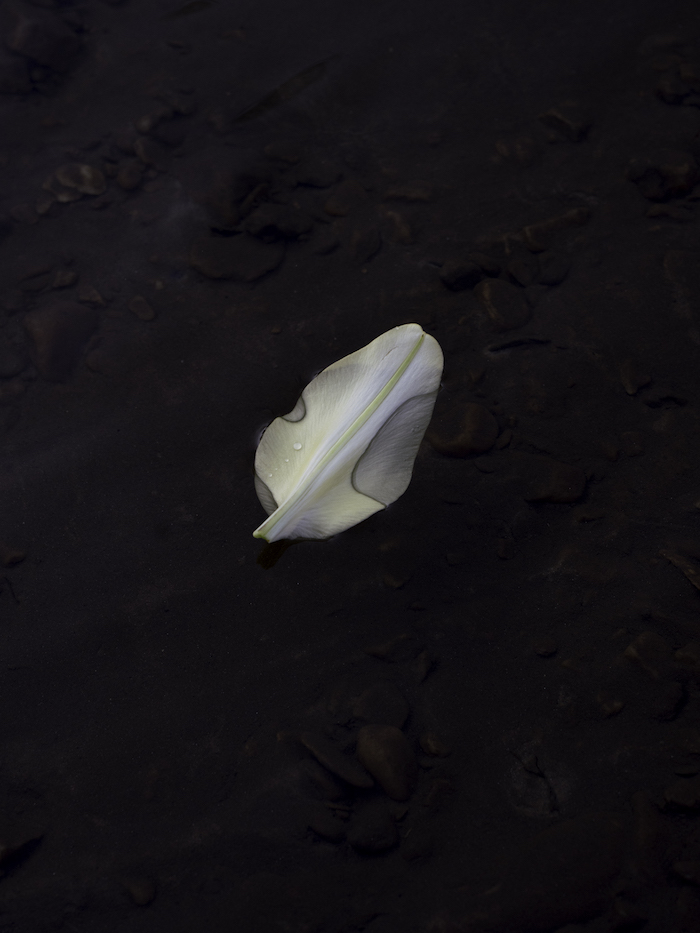

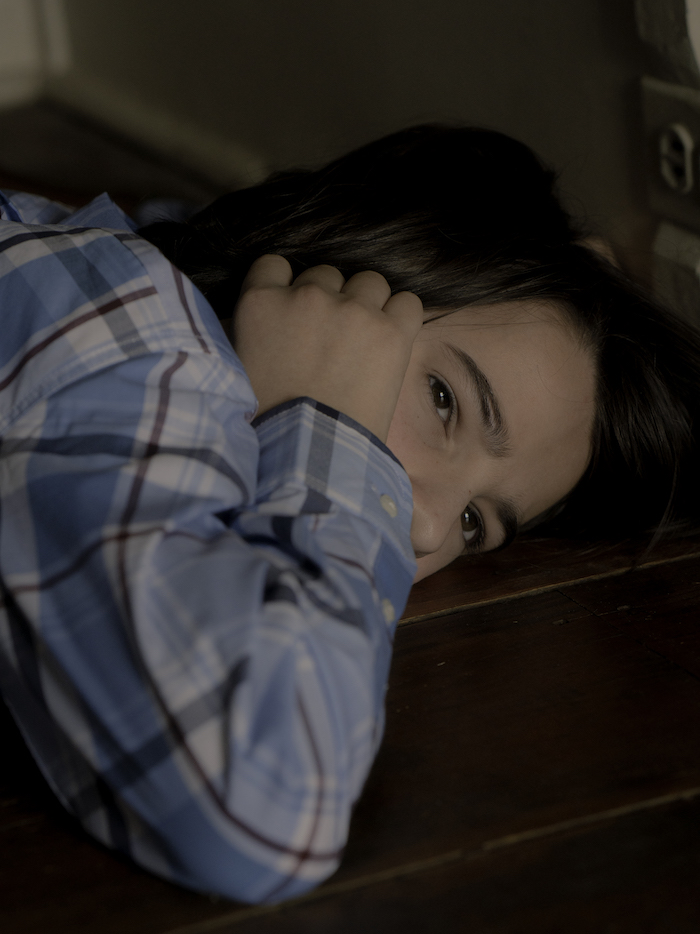

At first, you’re not quite sure what you’re looking at: a windshield blotted like a Jackson Pollock painting; twin smokestacks squatting over pale water; a sawn tree stump, so red at its center you’d think it was bleeding; land so dry it looks like a rash.

These are the images photographer Will Warasila captured in Walnut Cove, North Carolina, a small Piedmont community that has long been on the frontlines of a crisis. As in other American towns fighting environmental injustice, people of color and low-income residents are overrepresented in Walnut Cove, where nearly one in five residents is Black. The town is a twenty-minute drive from Belews Lake, constructed in 1973 by the Duke Energy corporation to provide cooling water for its coal-burning power plant, the Belews Creek Steam Station. The sprawling five-mile-long lake appears ideal for recreation, hosting a variety of leisure activities, including fishing, water-skiing, and boating. Less obvious is the history of the steam station itself: how the area has functioned as a storage basin for the power plant. How twelve million tons of coal ash have been kept there, unlined, seeping into groundwater and surrounding land. How the waste from the massive ash basin killed off most of the lake’s fish in the 1970s. How the neighboring communities, including Walnut Cove, fought for years to clean it up. How sickness—cancer, heart disease, neurological disorders—crept into their homes. As nuisance gave way to destruction, federal and state officials, as well as Duke Energy executives, gave few satisfying answers to the questions the community raised. At a 2016 federal hearing, members of the Walnut Cove community accused government officials of aiding the power company at cost to their lives.1

Warasila’s photos hint at both isolation and communion—the sort of contradictions not unusual in what environmental justice advocates call “fenceline” communities or, more pointedly, “sacrifice zones,” areas severely impacted by industry and the waste it produces. But while we know much about the dangers of lead poisoning and the impact of CO2 on the body, we know frustratingly little about coal ash, the toxic residue of coal production.2

Power companies have been dumping coal ash into pits and ponds since the 1700s. This type of pollution isn’t restricted by region. The states that generate the largest amounts of coal ash are spread throughout the South, Mid-Atlantic, and Midwest: Texas, Florida, Alabama, Kentucky, West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. But the country’s largest spills have occurred in the Southeast, the result of many years of disposing coal ash almost entirely in ponds, which is also considered the most dangerous and polluting method of removal.3

Coal ash can take many forms. It can travel through the air as fly ash—fine, powdery particles—or, if it gets funneled into waterways, it can become a toxic slurry. No matter what form it takes, however, its components are the same: a hazardous cocktail of lead, arsenic, selenium, and mercury, as well as other heavy metals. But while we know that the individual components in coal ash are harmful—no amount of lead or arsenic is safe for the human body—researchers don’t know how harmful these minerals are when they are combined.4

“There are so many people impacted by coal ash, yet limited research that tells us, ‘If you’re exposed, this is what your long-term impact is,’” says Kristina Zierold, an environmental health scientist and epidemiologist who specializes in studying environmental impacts on children’s health. Zierold is one of the nation’s leading researchers on the effects of coal ash. “There are cases of clustering of cancer around coal ash sites or where workers have been exposed. But again, that direct link between coal ash and cancer is not there.”

This is due to a number of factors. The gold standard of the scientific method would be to measure coal ash’s effect on a control group, but because the metals that make up coal ash are so toxic, this kind of study would be unethical as well as dangerous. As a result, researchers who have conducted studies about coal ash have had to extrapolate its effects based on what they know about its component toxins. Mercury, for instance, can be devastating for reproductive health. Lead can cause developmental disorders. Arsenic can lead to rashes and lesions.5

Researchers and environmental advocates have also observed the kinds of conditions that crop up in communities that neighbor coal ash dumps—dramatic increases in cancer rates, for example, or neurological issues among children. But even this can present challenges. The fenceline communities that border coal ash ponds and empilements typically are exposed to many different kinds of pollution—a rubber plant just around the corner from a power plant, for example. Socioeconomic factors also play their part. The people who live next to industrial zones are often politically marginalized: low-income households, people of color, underresourced communities where there are considerable barriers to accessing and affording adequate healthcare. Lacking resources and political clout, these communities see health issues in their neighborhoods compound, sometimes despite the best efforts of local reporting and activism or niche media. Towns like St. Gabriel, Louisiana, for example, typically only grab the attention of national publications, political leaders, or celebrities when they’re recognized as part of the constellation of impoverished communities known as “Cancer Alley.” It is one thing to be a slow killer. But what makes this slow violence so difficult to fight is the silence around it, all the things we don’t know and don’t see as coal ash courses through a community. “It would be better if you knew you’ve got an immediate rash or you get a runny nose or have blood coming from your ear if you got exposed to these things, because then your body would say, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’ve got the exposure, I need to do something about it,’” says H. Kim Lyerly, a professor in Duke University’s Department of Surgery, Pathology and Immunology, who recently completed a review of the components of coal ash and their known health effects. “Probably people would be more up in arms. The challenges with these exposures is that they are subtle and chronic and insidious, and that sometimes is the worst type of exposure you could have, because it doesn’t seem like you could do anything,” he continues. “And all of a sudden some tipping point occurs and you’re quite ill. And it’s almost too late at that point.”

Long-term exposure to pollutants can do more than rob a community of its health, notes Mustafa Santiago Ali, vice president of environmental justice, climate, and community revitalization for the National Wildlife Federation. Ali hails from Appalachia, across the river from an old coal plant. He recalls,

I watched my father go through cancer seven times, seven different cancers. And I watched my mother deal with cancer. I watched my baby sister deal with cancer. I watched my best friend’s mother and grandmother die of cancer. And our other very good friend’s father died of cancer. Sometimes it may take five, ten, fifteen years, sometimes maybe twenty years, to slowly begin to eat away at our bodies, and also at our spirits.

Going through multiple sicknesses in a family eats up time and money, as people may borrow against their homes to pay their medical bills. This means increased generational and communal insecurity—less money to pass down to children or share with neighbors or local organizations. It cuts careers short, forcing people to choose between going to school and taking care of sick family members. Pollutants like coal ash are a form of “slow violence, slow death,” Ali says, because they extract life, resources, and wealth from communities.

Industry incentives, of course, are profit-based. Companies like Duke Energy, Southern Company, DTE Energy, Talen, Ameren Corp, NRG Energy, and Luminant/Vistra Energy benefit from coal ash ponds because they are, simply, the cheapest way to dispose of coal ash. “We have about 30 percent of our energy that comes from coal,” Zierold points out. “But we are first in the world for generation of coal ash and storage.” It is one of the largest industrial waste streams here. And unlike other countries that store their coal ash in remote dumps, American industries have historically had little incentive to. Regulation has been minimal for coal plants as local, state, and federal governments favor industry investment and jobs over environmental concerns. The less these companies pay for safe disposal the more they profit.

The people who actually have to live with the effects of coal ash often have little influence in these decisions. Sometimes, this is by design, explains Lisa Evans, a senior counsel with the environmental advocacy group Earthjustice who has been working on coal ash since 2000. Before she joined Earthjustice, she worked with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), holding town halls with communities near waste sites. She recalls how scared and angry people were, how they demanded to know what the government would do to fix their water, their air.

“I believed in that job, and I believed in their right to come to me scared and angry and looking for answers,” she says. “And it’s the government’s job to give them answers and give them some hope. And we just turn this on their heads. We don’t even let them in the door.” She goes on, “The ability for low income communities and communities of color to effectively participate in rule-making is difficult at best.” And under certain governments, such as the Trump administration, further restrictions are placed on the process that prioritize industry needs and make community feedback all but impossible. In the last four years, there have been few public meetings hosted by the EPA to discuss proposed changes to coal ash rules, and a sixmonth window for the public to offer feedback on new guidelines dwindled to forty-five days.6

Because of this, we don’t know how far the consequences of coal ash actually extend. Evans notes that the EPA “has not once used” data from coal companies to require any further testing of drinking-water wells near coal plants, nor any testing of local water bodies to determine how far that contamination reaches. “Our knowledge of the contamination at many plants just ends at the plant boundary, and that is a ticking time bomb,” she says.

But there is still time to defuse some of the bombs, and Warasila’s images of Walnut Cove remind us of that. There is no reversing the rounds of chemotherapy and the wages lost. Coal ash can never be completely pulled out of the groundwater into which it has seeped. But further suffering is not inevitable. Governmental and educational institutions can fund sorely needed research into the health impacts of coal ash—an endeavor that would require serious relationship-building with residents who have, for many years, been an afterthought. Environmental advocacy groups and racial justice organizations have already been organizing residents to seek resources or have filed lawsuits on their behalf. Stricter regulations can be imposed on coal-producing power companies, requiring them to dispose of their waste away from residential areas and water sources. Better still, these companies could wean themselves away from coal production altogether, investing in clean technologies that could revitalize and bring new jobs to the very communities they’ve damaged.7

“[These] communities actually know a lot more than they’re given credit for,” Zierold points out. What they need are the tools and the support. Ali strikes a similarly hopeful note. “Yes, many of our communities have been trapped in this maze of exposures to toxic pollution. But there are escape routes,” he says. “Our communities don’t have to be trapped in that maze that people have created. It’s a maze of bureaucracy. It’s a maze of exposures. It’s a maze of disinvestments,” he continues. “We have an opportunity to create a twenty-first-century paradigm which will give our folks an opportunity to actually not just survive, but thrive.”

The Pollock-esque windshield captured in one of Warasila’s photographs is a quiet, unexpected testimony to this struggle. The eye, roaming the photo, eventually lands on hands holding the steering wheel, then perceives the washed-out road, visible even through the mud splatters. You are a phantom passenger, channeling the faith of the driver: even through the toxic sludge, there remains a path forward.

Addressing the Harm

by Will Warasila

The people of Walnut Cove, North Carolina, live in the shadow of Duke Energy’s Belews Creek Steam Station, where toxic coal ash is kept in a massive unlined storage pond, and toxins are pumped into the air, water, and soil. I spent the last year and a half getting to know the residents, the landscape, the structures of energy and power.

For the first few months, I explored Stokes County without making a photograph. I drove in circles around Belews Lake and the steam station, and through the towns that surround the lake. The more I visited, the more I got out of my car. Then I started trying to talk to folks.

In fall 2018, I was invited to a coal ash healing service at a church called The Well—an old house with a Moravian-style wooden sign outside, painted green and yellow with a white dove in the middle. On the far side of the house was a yellow and green striped tent with a stage at the back and rows of plastic fold-up chairs. The tent was about half full with a pretty diverse group of people. I sat down with them.

A middle-aged man spoke early in the service. “Four years ago you couldn’t pay me to be here, but now no one can pay me not to be here.” He described how his mother had passed away from cancer because of the toxic water, soil, and air in Walnut Cove. “This is not acceptable,” he said. “Duke Energy is trying to silence me with money; I will not be silent.” He started crying.

Pastor Leslie Brewer then gave her sermon, which has stayed with me. She said, “Bitterness will kill you quicker than coal ash.” And, “We must forgive Duke Energy for what they have done to the community and to the state, but that does not mean we have to remain silent. We must fight righteously. There is an army rising up.”

While trying to understand the slow violence of coal ash and the many issues surrounding the Belews Steam Station, I read a number of articles published by various news sources. The images that accompanied these stories show what you might expect: protests, speeches, the steam station, and, occasionally, a bird’s-eye view of the lake and coal ash pond. More often than not, the writer and the photographer dropped in and out of the community very quickly. As I dug deeper into the concerns of Walnut Cove, I realized that I was trying to find a different path. During my first recorded interview with Pastor Leslie, I asked her, “What is coal ash?” At first, she replied that it’s simply a nuisance. “Coal ash is what you got all over the cars and the roofs and anything you left outside. … Then it changed from a nuisance into a poison.” Growing up, she and her family could see “Belews Creek flowing by, and we’d swim in it. After the steam station was built, it became a sort of wasteland.”

Most of this transformation, the harm done to the land and its residents, is invisible. Nevertheless, I have attempted to make photographs that address this harm.

This essay first appeared in the Human/Nature Issue (vol. 27, no. 1: Spring 2021).

Will Warasila is a photographer and North Carolina native. He received a BFA in photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York City and an MFA in experimental documentary arts from Duke University. His photographs have appeared in the Oxford American, New Yorker, and New York Times, among other publications.

Anne Branigin is a journalist and essayist. She works as a reporter for The Lily, the Washington Post‘s publication centering on women’s stories. Previously, she was a staff writer at The Root, covering politics, social justice movements, health, and the environment through the lens of race and equity.NOTES

- “Walnut Cove, NC,” Data USA, accessed January 14, 2020, datausa.io/profile/geo/walnutcove-nc#; Taft Wireback, “What Will Be Done with Coal Ash at the Belews Creek Plant? Find Out at This Public Hearing,” Greensboro News and Record, February 18, 2020, greensboro.com/news/local_news/what-will-be-done-with-coal-ash-at-the-belews-creek-plant-find-out-at/article_c34828c4-e9f8-50be-8241-a7025c5f9511.html#; Taft Wireback BH Media, “Coal Ash Disposal Hearings Set for Belews Creek, Five Other Duke Energy Plants,” Winston-Salem Journal, January 20, 2020, journalnow.com/news/local/coal-ash-disposal-hearings-set-for-belews-creek-five-other/article_cba7adf7-6fd6-5388-b213-0054e6b8d0eb.html#; Nicholas Elmes, “Federal Hearing on Coal Ash Held in Walnut Cove,” Stokes News, April 7, 2016, www.thestokesnews.com/news/4462/federal-hearing-on-coal-ash-held-in-walnut-cove. There is a wealth of sources on coal ash and the struggle against environmental injustice throughout the South. On “sacrifice zones” and the battle for adequate government protection against industrial pollutants, see Steve Lerner, Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010). On the long relationship between structural racism and the environment, see Carl A. Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2015). For the impact of climate change and pollution on marginalized communities, see Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011). On the NAACP’s fight against environmental racism in North Carolina, see Common Dreams, “From Fracking to Coal Waste, NAACP Confronts Environmental Racism in North Carolina,” Facing South, June 4, 2015, https://www.facingsouth.org/2015/06/from-fracking-to-coal-waste-naacpconfronts-enviro.html.

- Mustafa Santiago Ali, in discussion with author, October 2020. This and further references to Ali from this conversation. Herbert Kim Lyerly, in discussion with the author, October 2020. Further references to Lyerly from this conversation.

- Lisa Evans, in discussion with the author, October 2020. This and further references to Evans from this conversation.

- Kristina Zierold, in discussion with the author, October 2020. This and further references to Zierold from this conversation.

- Lyerly, discussion; Geir Bjørklund, Jan Aaseth, Maryam Dadar, Monica Butnariu, and Salvatore Chirumbolo, “Exposure to Environmental Organic Mercury and Impairments in Human Fertility,” Journal of Reproduction & Infertility 20, no. 3 (2019): 195–197; “Lead Poisoning and Health,” World Health Organization, August 23, 2019, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health; Saeed Dastgiri, Mohammad Mosaferi, Mohammad A. H. Fizi, Nahid Olfati, Shahin Zolali, Nasser Pouladi, and Parvin Azarfam, “Arsenic Exposure, Dermatological Lesions, Hypertension, and Chromosomal Abnormalities among People in a Rural Community of Northwest Iran,” Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition 28, no. 1 (February 2010): 14–22.

- “EPA Proposes First of Two Rules to Amend Coal Ash Disposal Regulations, Saving Up to $100M Per Year in Compliance Costs,” Environmental Protection Agency, March 1, 2018, archive.epa.gov/epa/newsreleases/epa-proposes-first-two-rules-amend-coal-ash-disposal-regulations-saving-100m-year.html.

- Cat McCue, “Beginning of the End of North Carolina’s Coal Ash Crisis,” Appalachian Voices, February 25, 2020, appvoices.org/2020/02/25/beginning-of-the-end-of-north-carolinas-coal-ash-crisis/.