“‘I am proud to be a farmer in the lowlands / A place where even squares can have a ball . . .'”

In the spring of 1975, as in previous years, Lochem organized its annual music festival. Lochem is a Dutch village in the rural eastern Achterhoek region (literally, “the back corner”), nestled near the German border. From the vantage point of Amsterdam, this part of the country is indeed the back corner—dense with wild forests and even wilder peasants. Achterhoekers not only seem untroubled about the way they are stereotyped by people in the country’s urban west, they take a certain pride in it. The town of Doetinchem boasts a football club, De Graafschap, whose supporters call themselves Superboeren (“Super Farmers”). Grolsch, first brewed in 1615 in Groenlo, another Achterhoek city, remains the beer of rural people across the Netherlands to this day. And members of the Dutch rock band Normaal all hail from this region.

Before their first big show at Lochem’s festival, Normaal practiced songs by Chuck Berry, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Creedence Clearwater Revival. They also included Merle Haggard in their repertoire, which was unusual for a band whose front man used to be a hippie. “I loved Merle, even back then,” lead singer Bennie Jolink said. “He was a straightforward country and western artist who sang songs that were unpolished and sounded real.” Normaal adapted Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” to reflect their life in the Achterhoek. They did not sing about burning draft cards, long hair, and flying Old Glory in front of the courthouse, but about beer and the local football club:

I am proud to be a farmer in the lowlands

A place where even squares can have a ball

De Graafschap is our favourite in football

and Grolsch is still the biggest thrill of all.

Haggard’s transformed song was one of the first numbers in which Normaal aligned itself with Dutch farmers.1

Normaal opened the concert in Lochem at nine o’clock in the morning, by which time most of the band members were already drunk. But their performance of rock ’n’ roll songs like “Godveredomme, waor doe ik ’t veur” and “De Drieterije Blues” struck a responsive chord with audience members and critics alike. Performed in both Dutch and regional dialect, the lyrics had a raw and vulgar edge. As Oor music magazine reported, “The fact that singer Boozin’ Bennie expresses his joys and sorrows in an undiluted Gelders dialect was the most peculiar part of the Normaal concert. It is amazing how truthful the lyrics sound. If he sang them in standard Dutch, these songs would not make sense at all.” That morning in Lochem, at the Dutch countryside’s equivalent of Woodstock, Normaal began its quest to redeem the farmer and the rural Netherlands.2

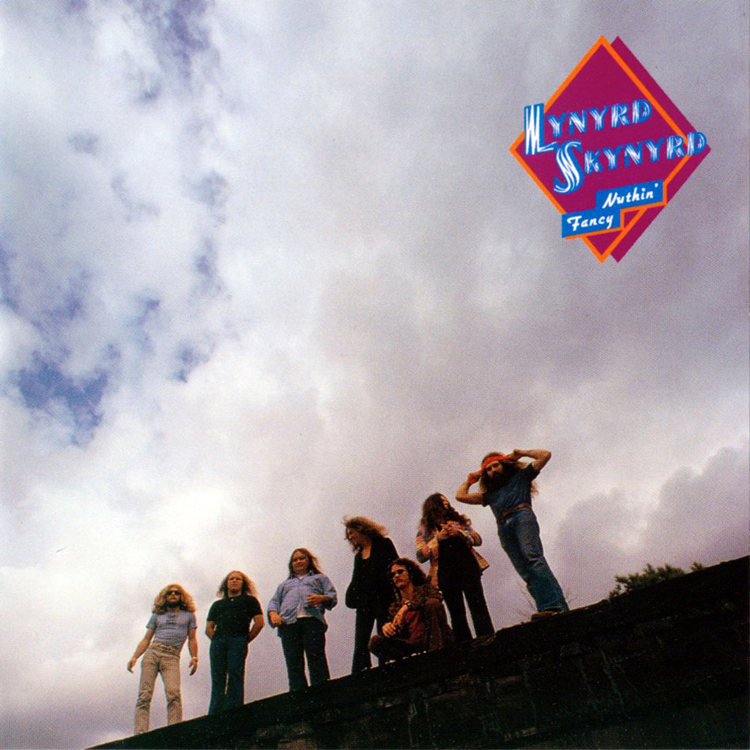

Across the Atlantic Ocean that same year, southern rockers Lynyrd Skynyrd released their third album Nuthin’ Fancy, featuring “Saturday Night Special,” “I’m a Country Boy,” “Whiskey Rock-a-Roller,” and “On the Hunt.” Most of the numbers dealt with the white, male, working-class South’s rowdy side of life: violence, hard liquor, chasing women, picking cotton, and rambling. Like Normaal, Skynyrd proudly sang about their rural upbringing and the differences between town and country. As Ronnie Van Zant declared on Nuthin’ Fancy,

But one smell from the city

And this country boy is gone

Big city, hard times never bother me

I’m a country boy, I’m as happy as I can be.

Skynyrd had already voiced a similar message in previous songs, including most notably in their ultimate hit, “Sweet Home Alabama.” Lynyrd Skynyrd was not very well known in the Netherlands during the height of its popularity in the States, the early and mid-1970s. In fact, news of Skynyrd’s plane crash barely made it into Dutch newspapers. The parallels between Lynyrd Skynyrd and Normaal are therefore striking, considering the relative obscurity of the southern rock band in that country.3

Similarities between the American South and the Netherlands’ countryside have not gone completely unnoticed. In a short, insightful essay that appeared in these pages, historian Edward Ayers discussed transnational North–South parallels that he observed as a visiting scholar at the University of Groningen in the country’s rural, northeastern corner. “My Dutch students and colleagues did understand regionalism,” Ayers wrote. “They warned me when I headed to Amsterdam for meetings that people would make fun of Groningen, as indeed they did . . . In their eyes, the North was colder, wetter, lacking in most redeeming qualities, full of empty space and cattle. It was as if the United States had been turned upside down . . . A sense of place, and the resentment, pride, and arrogance that accompany it, appeared throughout Europe just as it does in the South.” Although many scholars have described the South as an exceptional and inimitable place, cultural traits are obviously shared across the globe and are often reflected in song.4

Music functions not only to reflect but often to mobilize feelings of regionalism.

Evoking regional characteristics in their songs helped Normaal and Lynyrd Skynyrd create a sense of community among listeners with similar backgrounds. This relationship between musical message and audience recognition helps to explain the popularity of both Normaal and Skynyrd. “At Normaal concerts, there are 3,000 to 4,000 people who all think the same,” a fan from the Achterhoek asserted. “Normaal still sings about farmers as real men, super farmers, and when you’re at one of these performances you just feel a shiver going down your spine, because you see that there are still so many people who think the way you do. You don’t experience this anywhere else, only at Normaal concerts.” As experienced by this fan and many others, music functions not only to reflect but often to mobilize feelings of regionalism. Lynyrd Skynyrd and Normaal both represented the rebellion of the countryside, but in the case of Skynyrd, their defense of the South was inextricably linked with the region’s troublesome history of slavery and segregation.5

Proclaiming Regional Identity

In 1970, Canadian singer Neil Young released his album After the Gold Rush, which included the song “Southern Man.” Two years later, another Young album came out, featuring “Alabama.” Both songs were a response to the long legacy of bigotry in the South, in particular Civil Rights clashes in Birmingham and Selma in the early-to mid-1960s, and the rise in power of Governor George Wallace. Young sang of the South:

I saw cotton

and I saw black

Tall white mansions

and little shacks

Southern man

when will you

pay them back?

I heard screamin’

and bullwhips cracking.

Lynyrd Skynyrd objected to this view. “We played a lot in Alabama and we liked it,” guitarist Gary Rossington said. “We’d hear Neil Young’s ‘Southern Man’ and ‘Alabama,’ and we thought, ‘Hey, he’s from Canada, he ain’t never been here, so he shouldn’t cut it down.’” In response to Young’s denunciation of the South, Skynyrd quickly wrote “Sweet Home Alabama”—their greatest hit. The story goes that guitarist Ed King played the tune for Van Zant (apparently, the music had come to him in a dream), after which Ronnie wrote the lyrics in approximately fifteen minutes. Five days later, the band recorded the song as part of their new album Second Helping.6

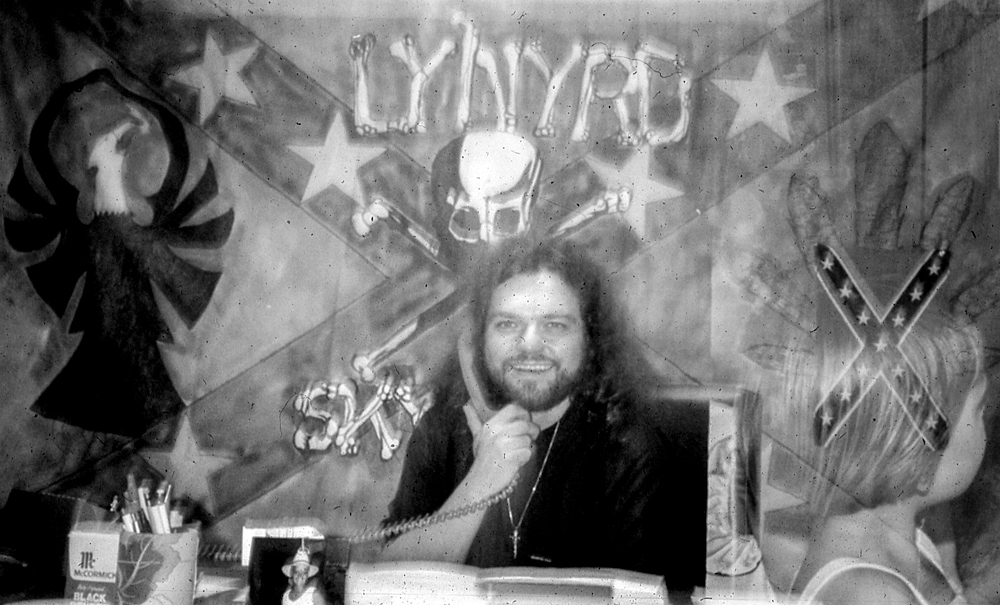

Although the original goal of the song was to rebuff Young, “Sweet Home Alabama” quickly transformed into a twentieth-century version of “Dixie,” a glorification of Skynyrd’s New South homeland. Its popularity perhaps indicated how the times were changing in the 1970s, as the post–Jim Crow South became the central component of a vibrant Sunbelt culture. The song was an instant success across the nation despite the neo-Confederate sentiments attached to it. At the same time, the connections between Skynyrd and the Confederacy grew stronger. Every time the band played the song on stage, an enormous Confederate battle flag unfurled behind them. And in the spring of 1975, Skynyrd’s members were declared honorary lieutenant colonels in the Alabama state militia. “We received a plaque from Governor George Wallace to become a lieutenant colonel in the state militia, which is a bullshit gimmick thing,” Ronnie Van Zant later said. Van Zant’s statement demonstrates the band’s ambivalence about the larger political implications of its records and performance on stage. Still, “Sweet Home Alabama” solidly linked Lynyrd Skynyrd with a defiant white South.7

“Sweet Home Alabama” was an instant success across the nation despite the neo-Confederate sentiments attached to it.

The song typifies a rural attitude of rejecting outside commentary on the countryside’s seemingly backward culture and the “circle the wagons” mentality that results. Sociologist John Shelton Reed discusses this notion in a book on southern cultural distinctiveness, arguing, “Also operating to offset the tendency toward fragmentation is the frequent presence, sometimes contrived, of external ‘threat.’ The South is never more united than when it feels the North picking on it or pushing it around.” Lynyrd Skynyrd was part of an assertive, self-confident “New” South, as Normaal was of a “New” Dutch North.8

In essence, the relationship between the western Netherlands—in particular, the urban area known as the Randstad, which includes Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht—and the Dutch countryside is based on the same center–periphery dynamic that defines the relations between North and South in the United States. Until at least the beginning of the twentieth century, the northeast of the Netherlands was considered a semi-colony that had little political power. In the nineteenth century, poor people and prisoners from the western parts of the country were transported to the province of Drenthe to work in the peat fields as indentured servants. Companies from the West were in charge and made huge profits over the backs of these laborers. Villages in Drenthe such as Nieuw-Amsterdam, Nieuw-Dordrecht, and Hollandscheveld (meaning, “Holland’s field”) are still reminders of that time. Further to the south, textile barons employed a labor system that was similar to the northeast. The structural exploitation of cheap labor bred a culture of distrust in these provinces. Current controversies about earthquakes caused by state-directed gas drilling in the North keeps this culture alive.

Since the heydays of the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century, the West played a dominant role in the nation’s politics and economy. During the so-called Dutch Golden Century, the Netherlands became synonymous with its two most western provinces, commonly known as Holland. Normaal was the first provincial rock band to successfully challenge this regional hegemony. “The explosion that was caused by Normaal can be explained in only one way,” former band manager Joost Carlier stated. “The main reason was the oppression since the Golden Century, the dominance of the western cities. Only Holland counted, the rest of the country was nothing. Normaal destroyed the yoke of the Golden Century.”9

Language was one of Normaal’s most important weapons against the dominant culture. In the Netherlands, the western dialect is known as Algemeen Beschaafd Nederlands (ABN) or “Civilized Dutch.” Other dialects, and especially those spoken in the northeast and south of the country, are generally considered to signify backwardness, ignorance, and a farmer mentality. Normaal turned these ideas upside down. Although they sang some songs in English during their first concert, the band later performed in dialect only. Dutch had never been an option for Normaal. “abn is synonymous with the Randstad, which has a lot of negative connotations for artists who sing in dialect,” Dutch musicologist Louis Peter Grijp wrote. “It is linked with western bravado, the loss of traditional values, the destruction of nature.”10

Jolink tried to be a hippie rebel in Amsterdam, but most of his urban colleagues considered him a hillbilly.

One important difference between Normaal and Lynyrd Skynyrd is that the latter’s white audience had a much more complicated relationship with race. The Netherlands never had institutionalized slavery within its current territorial borders, although the Dutch played a vital role in the slave trade, imported Africans to work on the plantations in their colony of Surinam, and installed a system of indentured servitude in the Dutch East Indies that came close to southern slavery in brutality and magnitude. But this dark page in the country’s history is not a defining part of its national consciousness, especially in comparison to the United States. Until the 1960s, racial tensions only existed on a small scale in the Netherlands. With the influx of laborers from Morocco and Turkey, frictions between the original Dutch population and the new immigrants started to increase, particularly in the last couple of years. But the Dutch countryside is still very white; most migrants have settled in the big cities. This does not mean the absence of nativist sentiments in the rural Netherlands, however. Jolink has frequently denounced such xenophobic attitudes, for instance in his 1994 song “Doe effen normaal.”

An experience that may resonate with many American southerners, Normaal singer Bennie Jolink personally encountered westerners looking down on people who spoke with an accent. In 1968, he left his hometown of Hummelo in the Achterhoek to study at the Academy of Arts in Amsterdam. He was happy about his move to the West; for a young artist, work and inspiration were scarce in the countryside. But disillusion soon replaced his enthusiasm. “Every time we had a meeting of the theater group, I would wear these trendy suits,” Jolink recalled. “Of course, I had nothing to say, until the subject changed to décors. All of a sudden, everybody would turn to me, to the angry young artist from the East of the country, who would explain how to take care of things. But as soon as I opened my mouth, their faces went blank. I tried to speak ABN, but my strong accent messed everything up. I could hear them think, ‘Oh, he’s a farmer, a hayseed,’ which obviously implied that I wasn’t able to say anything intelligent or interesting.” Jolink tried to be a hippie rebel in Amsterdam, but most of his urban colleagues considered him a hillbilly.11

Just like Neil Young’s songs triggered Lynyrd Skynyrd’s regional defense mechanism, Jolink’s experiences in the Dutch capital spurred him to assert his regional identity. Jolink returned to the Achterhoek in 1969, married his girlfriend Anneke, and realized what he had missed during his time in Amsterdam. “Darn,” he said, “look at the place where I came from: there is no better place than where I was born.” Normaal devoted one of its first songs to this particular site. “Hummelo” lambasted the fast life in the city, its drug problems, urban decay, and the claustrophobic atmosphere. In the Achterhoek there was space to live and move around, to ride a motorbike to a rough party in the countryside. “I’m glad I left,” Jolink sang of his return to Hummelo. “At least the people understand me here.”12

Farmers, Helluvafellas, and Rebel Rock

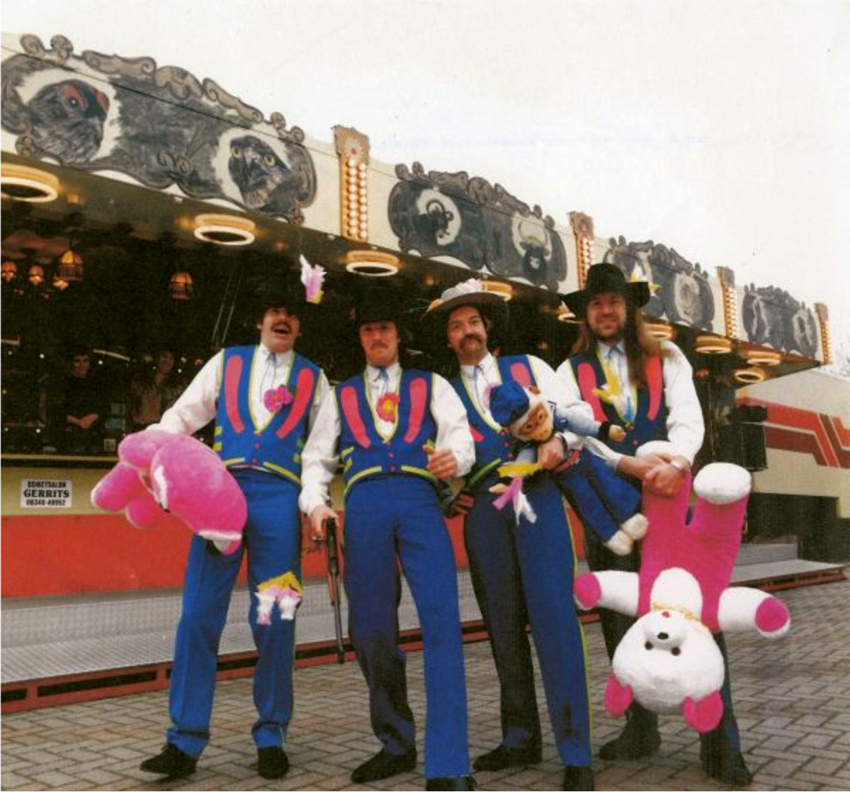

Jan Ottink, another singer who hails from the Achterhoek, once said of singing in dialect: “You can’t translate your feelings in English, because it’s not your own language and because people only understand half of it. At the same time, you’re not bothered by clichés, because dialect has not been used often in pop music. You have to invent your own tradition.” This is exactly what Normaal did through their music and performances. To express their sense of authenticity, they bought their over-sized suits at the Salvation Army and kept stage lightning to a bare minimum: a lamp typical of construction sites. Even in their name, Normaal redefined what was common. Old images were reinvented and used for new purposes. What was for some a badge of backwardness became a badge of honor for Normaal.13

Both Normaal and Lynyrd Skynyrd represented rural working class whites. The symbols Skynyrd used to do so, however, were often loaded with racist implications.

Skynyrd used similar tactics to reinvent the so-called “helluvafella” tradition as an accepted way of life. As journalist Mark Kemp wrote of the band’s early years, “Lynyrd Skynyrd was cultivating a reputation for being an intimidating and belligerent band of hard-drinking rednecks, and it began to work in their favor.” On stage, the band displayed markers of their identity by singing in thick southern accents and displaying a huge Confederate battle flag. Although Van Zant told Nat Freeland of Billboard that use of the flag was a gimmick by MCA Records, the band was undeniably proud of its southern heritage. “He loved the fact that he was from Dixie,” said Ronnie’s father, Lacy Van Zant. “Every song and lyric he sang told the story of growing up in the South. He spoke like a true rebel. The word ‘door’ was pronounced as ‘doah,’ a ‘floor’ was pronounced ‘floah,’ the word ‘more’ was drawled out to sound like ‘moah.’ And the more fun poked at Ronnie about his Southern accent, the thicker the drawl rolled from his lips.” Both Normaal and Lynyrd Skynyrd represented rural working class whites. The symbols Skynyrd used to do so, however, were often loaded with racist implications. The Confederate flag stood for the band’s rebellious character, but precisely because they used the banner, it became difficult to distance their rebellion from white supremacist sentiments.14

W. J. Cash describes the helluvafella in The Mind of the South, saying, “This character is of the utmost significance . . . And being what they were—simple, direct, and immensely personal—and their world being what it was—conflict with them could only mean fisticuffs, the gouging ring, and knife and gun play.” Historian Ted Ownby has argued a connection between the helluvafella and violence in southern rock. In “Saturday Night Special,” for instance, Van Zant sings about the disastrous results of a night out drinking and gambling:

Big Jim’s been drinkin’ whiskey

And playing poker on a losin’ night

Pretty soon, Big Jim starts a thinkin’

Somebody been cheatin’ and lyin’

So Big Jim commences to fightin’

I wouldn’t tell you no lie

And Big Jim done grab his pistol

Shot his friend right between the eyes

Fighting was part of Skynyrd’s rough-and-tumble image, especially after they had been drinking. Then, fistfights would erupt, even among each other. When Lynyrd Skynyrd was on tour in Europe to promote the release of their album Gimme Back My Bullets, Ronnie cut Gary Rossington’s hand and wrists in a drunken rage. The fight began because they could not agree on how to pronounce “schnapps,” leaving Rossington to play the guitar with just two fingers on the frets during the next ten shows. On stage, Bass player Leon Wilkeson often played up the role of a fighter, appearing dressed as a cowboy with pearl-handled pistols set in cream-colored holsters. And the song “Mississippi Kid,” which appeared on Skynyrd’s first album Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd, centers on a similar character: “I’ve got my pistols in my pockets boys, I’m / I’m Alabama bound / Well, I’m not looking for no trouble / But nobody dogs me ’round.”15

Many of the folks in Lynyrd Skynyrd’s songs spend their time on the road or in bars and honkytonks. On Street Survivors, the last album released before the band’s 1977 plane crash, which killed several members, Skynyrd covered Haggard’s “Honky Tonk Night Time Man,” which tells the story of a man who can only live at night in the bar. Haggard was a hero to both Van Zant and Jolink, which is not surprising given Haggard’s defiant defense of America’s rural heartland during the late 1960s with songs such as “Okie from Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me.” As critic David Cantwell declared, “In ‘Okie’ and ‘Fightin’ Side,’ and in countless country radio hits since, the country audience is conceived not only as distinct from other groups, but in contemptuous opposition to them. Its members were not merely patriotic, but true Americans, defending their values from derision and assault.” This dynamic was central not only to Skynyrd’s songs, but to Normaal’s as well. In the band’s repertoire, the countryside was a center of authenticity, contrasting sharply with the superficial nature of life in the big city. Experiences in the country are presented as more intense, more genuine, and more real.16

Through Haggard, Skynyrd and Normaal tapped into a music tradition known as hard country—a genre that eschews dominant cultural conventions. As literary critic Barbara Ching defines, “hostile relations with mainstream culture are . . . essential to hard country music.” Haggard’s oeuvre describes the hardscrabble lives of working-class people through narratives (primarily hardships) of truck drivers, field hands, and factory workers. The characters are generally not en route from rags to riches, but getting drunk in a rundown café to get away from the drudgery of everyday life. “Workin’ Man Blues” provides an excellent example. In it, a laborer explains how hard he has to work during the week to provide for his wife and nine children. He sometimes thinks about leaving, but a sense of duty toward his family keeps him in his old routine. Drinking beer, either at home or in the tavern, offers a temporary escape. Hard country is not about living the American Dream or living among the idyllic rural scenes prevalent in mainstream country music; it instead bemoans the challenges of rural life, especially the inescapability of being born poor.17

Haggard’s compassion for working class Americans earned him the title ‘Poet of the Common Man.’

Haggard’s compassion for working class Americans earned him the title “Poet of the Common Man.” Lynyrd Skynyrd and Normaal have claimed a similar label for themselves. From the start, Normaal branded itself as an advocate for the rural working class, singing songs about the difficult circumstances farmers encounter. “De boer is troef,” released in the early 1980s, recounts the uncertainties of agricultural life. Luck sometimes swings the farmer’s way, but as soon as he seems triumphant, he runs into the limits of his working class environment, in this case regulations by the European Union. Yet he remains proud to be a farmer. Other Normaal songs have a similar message. “De boer dat is de keerl” is about farmers being stuck in a vicious cycle of debts and taxes, while “Ik vuul mien zo zo” is a song about a guy who has hit rock bottom. Rural pride serves as a shield against the intrusions of the system, another marker of affinity with Haggard. Normaal lyrics have a defiant edge toward outsiders who look down on the countryside— a message that is very recognizable to a lot of people in the rural Netherlands. In positing a binary between non-urban regions and the Randstad, Normaal “has constructed a regional identity for the entire Dutch countryside, instead of an identity for a particular province or rural part of the nation.” Life in the Achterhoek thus became synonymous with life in Drenthe, Fryslân, or any other place outside the city.18

The message of Haggard’s “Okie” is ambivalent, however, and not just a badge of “redneck provincialism.” As Ching has argued, the lyrics can also be understood as a vilification of the bourgeois attitudes of people living in Muskogee, an interpretation that is often overlooked by other artists’ “responses” to the song. One of the few singers that incorporated the complex character of “Okie” into his own music was hard country artist David Allan Coe, whose “Longhaired Redneck” openly rejects the middle-class manners and outlook of Haggard’s Okies and claims that rednecks can also wear earrings and have long hair. Lynyrd Skynyrd and Normaal, of course, combined similar features in both music and appearance. Just as their long hair flouted bourgeois conventions, their songs celebrated redneck defiance.19

Although Normaal adopted elements of the hard country tradition, they also embraced mainstream country. Creedence Clearwater Revival (ccr), a band from the free-loving capital of San Francisco that developed a distinctly southern-influenced sound, was an influence for Normaal. The Dutch band played ccr songs during its early years and used country music to take a stand for the rural Netherlands. Normaal’s more positive take on life in the countryside also sets it apart from the hard country style, which moans “the blues of white-trash tragedy: broken homes, decrepit houses, binge drinking, dead-end jobs, and criminal records.” Unlike many hard country artists and Skynyrd front man Van Zant, Jolink grew up in a middle-class family. He saw his departure to Amsterdam as an escape from the oppressive culture of the Achterhoek, but returned when he found out that the hippie avant-garde in the big city was not very open to outsiders either—not even to rural intellectuals. When he discovered that singing in dialect evoked a very positive response from the audience in Lochem, he decided to embrace the country culture he once rejected.20

In a nod to more mainstream country themes, Normaal also focused on good times in the countryside. Their anarchistic attitude can be summarized in three words: høken, brekk’n, and angoan—synonyms for letting the good times roll. Many of the band’s songs are devoted to the fair, which is a major happening in small towns across the Dutch countryside. Together with annual motorbike races, the fair symbolizes a time of happiness, when the daily sorrows of rural life are forgotten and people are able to enjoy themselves. As Normaal sings in “Wi-j Goat Noar de Kermis”:

It’s harvest time in the countryside

We’re going to the fair

We all drink as much as we can

Young, old, poor and rich are going to the fair in the Achterhoek

Drinking beer and gin till we drop

The fair on the village square is not the only time or place to have fun, however, and Normaal is equally happy to celebrate the bar culture. One of Normaal’s most popular numbers is “Deurdonderen,” a song about a night in an Achterhoek honkytonk. The narrator enters a damp, dark bar, where a band plays loud rock ’n’ roll. A couple of guys want to fight with him, but the main character does not feel like it; he just wants to drink beer and have a good time with the girl he picked up that night.21

Sociologist Tom ter Bogt argues that Normaal concerts reflect audience members’ lived experiences. “One of the band’s most noteworthy accomplishments is the fact that not the musicians, but the audience itself is celebrated. Everybody is a farmer at these concerts, and this awareness creates a euphoric mood.” Normaal performances are displays of a determined countryside united against the West— a farmer rebellion against dominant social conventions. Straw is blown into the concert hall and plastic, beer-filled cups fly through the air. Sometimes it really looks as if the rural population is ready to take over Amsterdam. Concert tours are known as Veldtochten (“Campaigns”), and songs such as “h.a.l.v.u.” call upon all farmers to stand together. Though this Northeast–West divide is prominent, songwriter Jolink also condemns other ideological state apparatuses—the church, the bureaucracy, political parties—as hypocritical and pedantic. “Ik Bun Maor een Eenvoudige Boerenlul” brings all these frustrations together in a song unsparingly defiant: “I’m just a simple hick / and I’m not ashamed of that,” Jo-link sings. “I can make up my own mind / cause I’m not stupid.” Many listeners understood the meaning of these words; they might be considered provincial, but so was Normaal.22

Skynyrd performances were an unabashed celebration of the white, masculine South, as Confederate flags flew on stage and the bass player occasionally shot flares over the heads of the audience.

While Normaal’s shows glorified the Dutch countryside, Skynyrd performances were an unabashed celebration of the white, masculine South, as Confederate flags flew on stage and the bass player occasionally shot flares over the heads of the audience. Fans responded by throwing bullets on stage when the band performed “Gimme Back My Bullets.” “It was like Ronnie was the real deal, man,” George McCorkle of the Marshall Tucker Band said. “I think Ronnie wrote and talked about the average person. There is not a guy or girl probably that could not tell you they know ‘Freebird.’ Because there’s something in that song for everybody . . . And I think Ed King and those guys could write some stuff that talked to the average man. That’s exactly what Southern Rock and everything did. It hit on the workingman. That’s what Ronnie Van Zant did. Ronnie Van Zant was the people’s singer.” In the year of his death, Van Zant himself pointed out that “the guys in Lynyrd Skynyrd are nuthin’ but street people, right straight off the streets, skid row, the whole works. It’s very easy for us to relate to that. We can relate to that much more than anything else.”23

Through their revolt against the dominant conventions of middle class manners, decency, and civility, both Lynyrd Skynyrd and Normaal created a regional identity that refurbished accepted images of the U.S. South and the Dutch countryside. “Redneck” and a regional background became sources of pride. “Subcultures borrow from the dominant culture, inflecting and inverting its signs to create a bricolage in which the signs of the dominant culture are ‘there’ and just recognizable as such, but constituting a quite different and subversive whole,” ethnomusicologist Martin Stokes wrote about this tactic of revolt. The strategy of the bands was often based on reinforcing the negative national image of country people and thus subverting it. Loud music, hard drinking, fast driving, and wrecking cars were all part of the image they created of themselves. They were outlaws, who did not care about what other people considered to be socially acceptable.24

The Us-Them Dynamic

In their music, both Normaal and Skynyrd constructed stories about themes including violence, drinking, and partying in honkytonks that were very recognizable to a distinct regional audience. In the case of Normaal, dialect also played an important role in its repertoire. Simultaneously, different types of outsiders were created to represent the symbolic enemy. “When I was working on the farm / One of those import-westerners who just moved here / complained about the noise of my tractor,” Jolink sings. “That pisses me off.” In this song, not only people from the West, but also “Jesus freaks” and “funky freak bands that play intellectual music” are considered intruders. In “Sweet Home Alabama,” Skynyrd employed a similar theme by denouncing Neil Young. Through this us–them dynamic, regional artists create a positive image of their own region and redevelop what can be considered conventional. In the fast-paced life of modern society, Jolink and Van Zant told their fans there is honor in being a farmer or a simple man.25

The relationship between Skynyrd and the Confederacy reinforced their identity as rednecks, but it also created a racist edge to the band’s image.

Besides these similarities, however, distinct differences exist between regional rock music from the American South and the Netherlands. In the case of Lynyrd Skynyrd, the term “rebel” truly stood for something. The enormous Confederate battle flag that unfolded on stage as Ronnie sang “southern man don’t need him around anyhow” evidenced both a rebellious regional attitude in the present cultural moment (post–Civil Rights Movement) and played on the historical Rebel of the Civil War. The relationship between Skynyrd and the Confederacy reinforced their identity as rednecks, but it also created a racist edge to the band’s image, an impression only strengthened when they became lieutenant colonels in George Wallace’s National Guard. The burden of history never plagued Normaal much. In fact, some of their songs have a very progressive message. Recently, Jolink even criticized right-wing populist Geert Wilders because of his viewpoints on immigration and Islam.

Yet, like Skynyrd, Normaal’s popularity might also be explained by looking at the effects of modernization, urbanization, and globalization on the Dutch countryside. “A lot of questions about regionalism in the Netherlands are still unanswered,” Louis Peter Grijp observed. “For example, how can we explain the boom in regional music at the end of the 1980s? Was it a reaction on macro-developments such as urbanization, European integration, and globalization? Was it caused by the surge of regional broadcasting stations? How does music that is sung in dialect fit into the so-called dialect renaissance . . . ? And how does dialect music from the Netherlands fit into international developments?”26

In the Netherlands’ burgeoning dialect music scene, spurred by Normaal, regional musicians often use American music traditions that are related to the countryside. For instance, the band Rowwen Hèze, from the southern province of Limburg, applied Tex Mex and Cajun music to sing about their region. Blues singer Daniël Lohues from Drenthe formed the Louisiana Blues Club together with a couple of musicians from Louisiana and still performs in dialect. Folk-singer Ede Staal was the Townes Van Zandt of Groningen, while Cuby and the Blizzards recorded blues music in the small northern village of Grolloo during the 1960s. Jolink’s career as farmer-rocker will come to an end this year. After four decades in Normaal, he has decided that 2015 will be his last full tour with the band.

The songs produced by Normaal and other regional musicians demonstrate that rural music from the United States can be easily adopted and adapted by these artists to reflect on life in the Dutch countryside. Rural people do not live in isolation, but are open to influences from outside and use foreign music traditions to create a regional identity. “Listeners construct individual and collective musical worlds out of sounds that they make themselves and sounds that they do not,” popular music scholar Karl Hagstrom Miller explained. Simultaneously, cultural values that are considered unique to a certain region might be comparable to the codes of behavior in other parts of the world, like the South of the United States and the North of the Netherlands.27

Maarten Zwiers studied History and American Studies at the University of Groningen and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. He is currently assistant professor in History at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, where he teaches Political and U.S. History, with a specific emphasis on regional identity. In 2015, his book Senator James Eastland: Mississippi’s Jim Crow Democrat came out with Louisiana State University Press.

Header image: Lynyrd Skynyrd drum set by Kent Buckingham, Flickr.com, CC BY-NY 2.0.NOTES

The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

1. Jos Palm, Oerend Hard: Het Onmogelijke Høkersleven van Ben Jolink (Amsterdam and Antwerp: Contact, 2005), 110. Jolink’s quote has been translated from Dutch; Normaal’s adapted lyrics of “Okie from Muskogee” were in English.

2. Songs in dialect remain in the original; Quotes translated from ibid., 112, 114.

3. Lynyrd Skynyrd, “I’m a Country Boy,” Nuthin’ Fancy (LP; MCA, 1975); Pieter Steinz, “Lynyrd Skynyrd,” NRC Archief, October 21, 2002, accessed April 25, 2015, http://vorige.nrc.nl/geslotendossiers/zwanenzangen/afleveringen_nieuwe_serie/article1567355.ece.

4. Edward Ayers, “When the North is the South: Life in the Netherlands,” Southern Cultures 4, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 46, 48.

5. Translated from Frank van den Engel, Normaal: Ik Kom Altied Weer Terug (DVD; RCV, 2002).

6. Neil Young, “Southern Man” (1970), After the Gold Rush (CD; Reprise/Wea, 1990); Quoted in Lee Ballinger, Lynyrd Skynyrd: An Oral History (Los Angeles: XT377 Publishing, 1999), 77.

7. Quoted in ibid., 80.

8. John Shelton Reed, One South: An Ethnic Approach to Regional Culture (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982), 179.

9. Quote translated from Palm, Oerend Hard, 173.

10. Translated from Louis Peter Grijp, “Is Zingen in Dialect Normaal? Muziek, Taal en Regionale Identiteit,” Volkskundig Bulletin 2 (October 1995): 321.

11. Quote translated from Palm, Oerend Hard, 69.

12. Quote translated from ibid., 93; Lyrics translated from Normaal, “Hummelo,” D’n Achterhoek Tsjoek (LP; Wea, 1979). All following Normaal lyrics have been translated into English by the author.

13. Quote translated from Grijp, “Is Zingen in Dialect Normaal?,” 311.

14. Mark Kemp, Dixie Lullaby: A Story of Music, Race, and New Beginnings in a New South (New York: Free Press, 2004), 78; Quoted in Marley Brant, Freebirds: The Lynyrd Skynyrd Story (New York: Billboard Books, 2002), 94.

15. W. J. Cash, The Mind of the South (1st ed. 1941; New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 43; Ted Ownby, “Freedom, Manhood, and White Male Tradition in 1970s Southern Rock Music,” in Haunted Bodies: Gender and Southern Texts, eds. Anne Goodwyn Jones and Susan V. Donaldson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997), 371; Lynyrd Skynyrd, “Saturday Night Special,” Nuthin’ Fancy (LP; MCA, 1975). Although violent encounters characterize the first two verses of “Saturday Night Special,” the song takes an unexpected turn against guns in the last two verses, with Van Zant suggesting to “dump ’em people / To the bottom of the sea / Before some fool come around here / Wanna shoot either you or me”; Lynyrd Skynyrd, “Saturday Night Special,” Nuthin’ Fancy (LP; MCA, 1975). Gene Odom, Lynyrd Skynyrd: Remembering the Free Birds of Southern Rock (New York: Broadway Books, 2002), 125; Lynyrd Skynyrd, “Mississippi Kid,” Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd (LP; MCA, 1973).

16. David Cantwell, Merle Haggard: The Running Kind (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013), 167.

17. Barbara Ching, Wrong’s What I Do Best: Hard Country Music and Contemporary Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 6.

18. Bill C. Malone and Jocelyn R. Neal, Country Music, U.S.A. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 294; Translated from Louis Peter Grijp, “Is Zingen in Dialect Normaal?,” 321. Emphasis mine.

19. Ching, Wrong’s What I Do Best, 41–44.

20. Ibid., 33.

21. Normaal, “Wi-j Goat Noar de Kermis,” 20 Jaar Normaal Onwys Høken (CD; Mercury, 1997). “Kermis” means fair in Dutch; Normaal, “Deurdonderen,” Deurdonderen (LP; Wea, 1982).

22. Quote translated from Palm, Oerend Hard, 171. Emphasis mine; Normaal, “Ik Bun Moar een Eenvoudige Boerenlul,” 20 Jaar Normaal Onwys Høken (CD; Mercury, 1997); Palm, Oerend Hard, 169.

23. Quoted in Brant, Freebirds, 113; Quoted in Odom, Lynyrd Skynyrd, 1.

24. Martin Stokes, “Introduction: Ethnicity, Identity, and Music,” in Ethnicity, Identity, and Music: The Musical Construction of Place, ed. Martin Stokes (Oxford, UK and Providence: Berg, 1994), 20.

25. Normaal, “Doar Baal Ik Van,” Hits van Normaal (CD; Telstar, 1994).

26. Translated from Louis Peter Grijp, “Van Dialectlied tot Boerenrock: Muziek en Regionale Identiteit,” Constructie van het Eigene: Culturele Vormen van Regionale Identiteit in Nederland, eds. Carlo van der Bogt, Amanda Hermans, and Hugo Jacobs (Amsterdam: P.J. Meertens Instituut, 1996), 106.

27. Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 17.