Just the other day, I read a lengthy piece suggesting that the Grand Ole Opry is about to fade away. Fans of “contemporary” country apparently don’t find Little Jimmy Dickens or Porter Waggoner terribly relevant, and the current chartbusters among the younger generation of artists are loathe to forgo the big bucks from lucrative road gigs for the paltry $500 or so that the Opry pays. Such news is certain to set off a new season of wailing and hand-wringing from those who fear the imminent demise of so-called “traditional” country music. Before we get too lathered up, however, let me point out that we’ve heard all this before. Actually, every time Garth Brooks or one of his big-hatted buddies kicks off another over-hyped mega-tour or cuts a new CD, somebody tells us that if ol’ Hank were alive today, he’d be spinning in his grave.

Now, don’t get me wrong. The more “old fashioned” or “down home” a country song is, the better I like it. They simply don’t come to maudlin or twangy for this boy. Still, I’m not ready to throw in with those who reject everything they hear on the radio these days as nothing but over-produced, pop-oriented drivel and long for the good old days when times were bad and country music was a pure, unadulterated reflection of the life experiences of rural southern whites. As is often the case, these self-described “purists” are actuallyy worshiping something that was never pure in the first place.

In fact, as I see it, the entire history of country music reflects the manner in which southern culture at large has survived by accommodating rather than resisting the forces of change.

Technology, especially the advent of the phonograph and the radio, seemed to pose a formidable threat to the region’s traditions and values, yet these contraptions also served as vehicles by which southern music would reach listeners around the nation and ultimately the world. Likewise, technology brought other musical forms into the South and encouraged the lyric and stylistic intermingling and cross-fertilization that marked southern music from the beginning.

As early as the turn of the century, Harvard archaeologist Charles Peabody was dismayed to find Black southern workers singing not only hymns but “ragtime” tunes that were “undoubtedly picked up from some passing theatrical troupes.” By the time folklorists began their early field recordings in the South, as Francis Davis put it, “a supposedly authorless and uncopyrighted song learned by ear for generations might be in reality a song once featured in a vaudeville revue or written or recorded by some long-forgotten professional entertainer.” Historian Edward L. Ayers clearly had both early country music and the blues in mind when he observed that “what the twentieth century would see as some of the most distincdy southern facets of southern culture developed in a process of constant appropriation and negotiation. Much of southern culture was invented, not inherited.”1

For southern whites, the nostalgic and weepy Victorian parlor songs popular throughout the nation at the turn of the century were particularly appealing, and songs such as “Pale Amaranthus” were soon southernized into the famous Carter Family classic “Wildwood Flower.” Early recordings of southern rural musicians, Black and white, proved so commercially successful that recording companies quickly dispatched talent scouts who fanned out across the region in search of new singers and new songs. The quest for fresh material soon exhausted the available reservoir of folk, spiritual, gospel, and dance tunes and encouraged performers such as Fiddlin’ John Carson and Ernest V. “Pop” Stoneman to try their hand at songwriting. Although these early country composers frequendy retained the old Anglo-Saxon ballad format, they often lifted their subject matter directly from recent headlines. Not surprisingly, many of their songs expressed some significant misgivings about the impact of modernization. Stoneman’s “Sinking of the Titanic” deplored the sin of human arrogance and stressed the limits of human capability by pointing out that although the Titanic was billed as an unsinkable ship, “God, with his mighty hand, showed the world it could not stand.”

Country music pioneer Uncle Dave Macon seemed to be making a similar statement when he vowed, “I’d rather ride a wagon and go to heaven / Than go to hell in an automobile.” ( It is worth noting in passing that at this point Uncle Dave’s wagon-freight company had recendy been driven out of business by a trucking line.) As Charles Wolfe pointed out, however, “Uncle Dave was able to make his peace with technology” once “he was able to integrate it into his life.” As soon as traveling by auto became vital to Macon’s performing career, he began to sing the praises of the “Model T” in “On the Dixie Bee Line (In That Henry Ford of Mine).” Uncle Dave kept abreast of later developments by recording “New Ford Car,” a tribute to the newer, more comfortable “Model A” that succeeded the Model T.2

As time passed southern songwriters soon managed to harness the imagery of modern technology to moralist-traditionalist ends. The radio, which provided an ever-widening invasion route for the influences of mass society, also became an agent for indoctrination in Protestant fundamentalism. If you missed church on Sunday, all you had to do, as the tide of Albert Brumley’s 1937 gospel composition insisted, was “Turn Your Radio On” and “get in touch with God” by listening to “the songs of Zion coming from the land of endless Spring.” The same adjustment to new technology was playing out on the other side of the color line. This is apparent in the lines of songs popular among Black sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta:

Friend, I’m married unto Jesus

And we’s never been apart

I’ve a telephone in my bosom

I can ring him up from my heart

I can get him on the air [radio]

Down on my knees in prayer.3

Finally, the “trucker” songs of the post-World War II era suggest a growing belief in humanity’s inherent ability to win not just a stalemate with technology but a victory over it. In the hands of a hard-drivin’, pill-poppin’, bed-hoppin’, smokey-baitin’, “Truck Drivin’ Son of a Gun,” an eighteen-wheel diesel behemoth became as docile as a dutiful and pampered cowpony. Whereas the mysterious but tragic hobo of yesteryear romanticized by Jimmie Rodgers was forever “Waitin’ for a Train,” the truck driver was always in motion and firmly in control, confident that he was “gonna make it home tonight.” “Six Days on the Road” was little more than a joyride, especially if you were perpetually “ratchet-jawing” on your CB radio. The latter activity presented a prime example of high technology—harnessed and humanized, southern style. A classic illustration was “Teddy Bear,” a phenomenally popular ballad that told the story of a disabled but ever-chipper orphan lad whose deceased trucker father’s old CB was his only link to the outside world.

The pursuit of larger commercial markets intensified in the 1920s, and the more rustic country performers like Fiddlin’ John Carson gradually gave way to the decidedly more “modern” and innovative Jimmie Rodgers, who took hillbilly music into areas undreamed of a decade earlier, yodeling melodically, incorporating Hawaiian-style steel guitars and even the jazz stylings of Louis Armstrong into his songs. Before he died of tuberculosis in 1933, Rodgers sold twelve million records and at one point was earning more money than Babe Ruth. A slick-talking, Black-sounding hipster, Rodgers was a romantic, if ultimately tragic figure, and also one of the first hillbilly performers to don a cowboy costume.

As performers in the Depression-ravaged South realized that their audiences preferred the carefree cowboy to the down-and-out plowboy, the Southwest was busily producing yet another strain of country music, “western swing,” a marvelous synthesis of jazz and hillbilly with a little Cajun, Mexican mariachi, and polka thrown in as well. Almost solely the creation of Bob Wills, western swing stood out as a musical melange, blending the “big band” sound with the folk tradition. Wills’s signature song, “San Antonio Rose,” was also recorded by Bing Crosby, suggesting that the possibility of taking country music into the mainstream market was not as remote as it once had seemed.

Like western swing, World War II-era “honky tonk” was a music born in the midst of drinking, dancing, and often brawling. The sinful practices associated with honky-tonk music suggested the morally ruinous potential of modernization, and the lyric content seemed a radical departure from the moralism and Victorian restraint that marked the songs of the Carter Family, RoyAcuff, and many others who are viewed as country-music pioneers. Yet, as Tony Scherman rightiy notes, “In its sounds and lyrics honky tonk embodies country’s great complex of themes: the opposing tugs of country and city; the collapse of traditional supports like family, community, church; rural Americans’ hard adjustment to urban life.” Despite its controversial beginnings as a threat to the values traditionally upheld in country music, most of today’s fans would probably identify honky tonk as the pure essence of country music.4

Shortly after World War II the legendary Bill Monroe, revered by subsequent generations of fans as the personification of traditional, folk-derived music, actually revolutionized the old string-band sound by building his band’s offerings around the new three-finger banjo stylings of Earl Scruggs. The result was “bluegrass,” a decidedly jazzed up version of the old “high lonesome” sound that one scholar described as “folk music with overdrive.”5

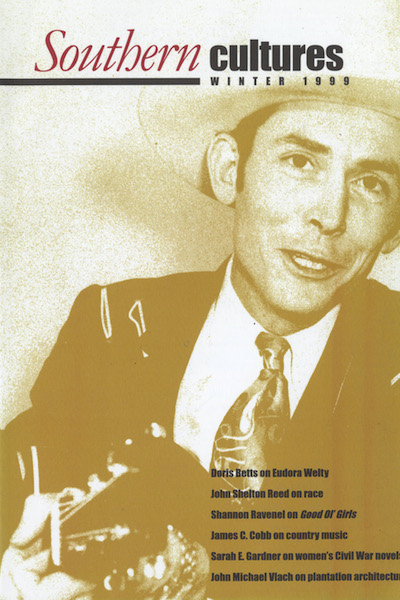

Actually, the performer whose emotional songs and tragic life seem most quintessentially “country” today is Hank Williams. Yet in its day, Williams’s style was both innovative and controversial. It combined country, honky tonk, and Black instrumental and vocal influences to develop a distinctive sound whose appeal shows remarkable endurance. Though Williams’s music now seems country through and through, his frequent reliance on a heavy beat and his physical ges- tures and gyrations onstage clearly made him controversial in more conventional circles and foreshadowed the style of Elvis Presley, the “King of Rock ‘n’ Roll.”

Some observers foresaw rock ‘n’ roll actually killing off its country-music ancestor. Country did suffer gready in the 1950s, but the 1960s saw a resurgence as the “Nashville Sound,” or “country pop,” offered the easy-listening sounds of artists such as Eddy Arnold and Jim Reeves. Patsy Cline, who is widely regarded today as the classic female country vocalist, actually made her enduring reputation as a country pop star who “crossed over” into the popular mass market with hits such as “Walking After Midnight” and “I Fall” to Pieces.” The Nashville Sound sold big, but the so-called traditionalists despised it. It elicited a sort of “neo-honky-tonk” reaction (the once suspect honky tonk had already become “traditional”) personified first by “The Possum” George Jones and later by the “Bakersfield Sound” of the great Merle Haggard, the “poet of the common man” whose “Okie from Muskogee” did so much to suggest the southernization of America.

And so it goes in a recurring dialectic wherein country music seems ready to fade completely into the enveloping blandness of the pop-music scene only to have a “new traditionalist” movement emerge. Current favorites Emmylou Harris, Ricky Skaggs, Dwight Yoakam, and Randy Travis have at one time or another worn the “new traditionalist” collar. Meanwhile, contemporary critics regularly heap waves of abuse on Garth Brooks for his relentless pursuit of the mass market with songs that substitute pina coladas for longnecks and stage shows that make the halftime extravaganza at the Super Bowl look like a third-grade Christmas pageant. Elsewhere, Shania Twain, whose husband once produced Def Leppard, juxtaposes fiddles and twangy pedal steel guitars with emphatic rock beats and stylings featured in songs by artists ranging from the Rolling Stones to The Police.

Certainly, libera America’s lamentations about country music’s ascendance in the 1970s seem ironic indeed in retrospect as the twentieth century draws to a close amid a flood of concerns about the South’s—and country music’s—loss of identity. For more than three quarters of a century, both those who listened to country music (many of whom also pretty much lived it) and those who performed it have struggled to reach the mainstream of American life. Having arrived, they must face up to the cultural consequences of their accomplishment, especially the loss of identity that total immersion may bring.

Social critics in the 1970s had fretted about country music’s soaring popularity because of its ostensibly reactionary ideological agenda, but music critics of the 1990s complain that the music has no agenda at all, ideological or otherwise. Their argument goes something like this: Settled into a comfortable suburban existence, its traditional core constituency, or at least the heirs thereof, no longer needs or wants to hear songs about suffering, struggle, tragedy, death, and damnation. Consequendy, the once unapologetically candid and gritty idiom that expressed real struggle and genuine alienation from the unfamiliar urban-industrial environment now serves up little more than mass-produced, smoothed-out suburban escapism. When detractors dismiss Garth Brooks as the evil “anti-Hank,” however, they fail to realize that, like Brooks, Williams and a number of the other “pioneers” who are now enshrined in the Hall of Fame were also seen in their own day as threats to country music’s identity and integrity. When Tony Scherman asks, “How far from its social origins can an art form grow before it simply loses meaning?” he ignores the fact that country music’s “social origins” are in a South that was anything but static as it adapted to a slew of changes, including industrialization, urbanization, and die cultural fallout from technological advances such as the phonograph, the radio, and the automobile.6 As time passed, the changes in country music have reflected the Americanization of Dixie just as its soaring popularity nationwide has documented the southernization of America. Before we offer up any more premature obituaries, let’s remember that, to paraphrase Hank Jr., for country music, change is actually a family tradition.

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

James C. Cobb is a professor emeritus of history at the University of Georgia. A former president of the Southern Historical Association, he has edited and co-edited a number of books including The New Deal and the South, Perspectives on the American South, The Mississippi Delta and the World: The Memoirs of David L. Cohn, and Globalization and the American South.

Header: Porter Wagoner, by Les Leverett. Courtesy of the Grand Ole Opry Archives.

NOTES

This article was adapted from “Modernization and the Mind of the South” in James C. Cobb’s Redefining Southern Culture: Mind and Identity in the Modern South, (University of Georgia Press, 1999).

- Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction (Oxford University Press, 1992), 385, 377, 373; Francis Davis, The History of the Blues: The Roots, the Music, the People from Charley Patton to Robert Cray (Hyperion, 1995 ), 169.

- Charles Wolfe, “Uncle Dave Macon,” ed. Bill C. Malone and Judith McCulloh, Stars of Country Music: Uncle Dave Macon to Johnny Rodrigues (University of Illinois Press, 1975), 42, 59—62.

- Anonymous song citation, Samuel C. Adams Jr., “The Acculturation of the Delta Negro,” Social Forces, 76 (December 1997): 203.

- Tony Scherman, “Country,” American Heritage 45 (November 1994): 47—48.

- Alan Lomax, “Bluegrass Background: Folk Music with Over Drive,” Esquire 52(October 1959): 103–9.

- Scherman, “Country,” 57.