In October 1944, our ancestors Noah and Annie Riddick purchased roughly forty acres of land in Pantego, North Carolina. That land was both a homestead for sharecropping and, more important, a refuge for a southern Black family living at the height of Jim Crow. The land provided safety and sustenance for Noah and Annie’s eight children and, to this very day, their heirs. “Riddick Town,” this vast place, is tucked discreetly behind beautiful tree-lined fields off Old 97 Road. A road sign reading “Riddick Road” marks its location. It is ten minutes from the nearest urgent care and twenty minutes from “town” (Washington, NC). Pantego is situated in the North Carolina coastal plain and lies roughly five miles inland from the Pungo River, which pours into Pantego Creek. As Pantego is a small rural town of approximately one hundred sixty-four people, most of the land surrounding Riddick Town has been home to large, family-owned farms that employed many in the Pantego community with seasonal work producing crops such as corn, cotton, flowers, and tobacco. Over time, as agricultural production became more challenging and industries shifted their focus to manufacturing and technology, the town of Pantego has seen relatively little change in the landscape.1

Black folks often inherit land in Pantego from family members. Riddick Town is no different. As is the case with most Black farmland that was transferred to descendants as heirs’ property, our family has come to a moment that calls us to answer a critical question: What do we want to do with the land? And while this question is intimidating and severely complicated to answer, especially legally and financially, it has made us shift our perspective on our relationships in total—our relationships with each other, our history, our land, and our imagination.2

After my great-grandmother passed away in April 2020—leaving her home and parcel of land in Riddick Town to me—I felt called to establish a new relationship with the land. This required intentional (therapy-supported) reconnection with myself and the place I called home. I had spent most of my childhood in Riddick Town, being raised by my great-grandmother. Most of my childhood memories are about the time spent in the woods of Riddick Town, playing with animals, making mud pies, walking what used to be a dirt road, and running through and around our seasonal family gardens. Although I didn’t spend much time working in those gardens, I do remember a seemingly unlimited bounty of fresh vegetables, poultry, pork, and homemade biscuits—most of which I don’t remember going to the grocery store to purchase. It was somewhat apparent to me that the land we lived on was a source of provision for our basic needs and a conduit for learning, exploration, and community.

Presently, as a Black southern storyteller, multimedia artist, and archivist, I also know that land is a basis upon which generational wealth can be built and passed on. As I witness life in an urban area and the impacts of gentrification, houselessness, climate change, lack of food access, and economic uncertainty, I recognize the importance of access to land and place for people and communities. My childhood was proof that having a place to call home, rooted in placemaking on land, was essential to my family’s survival. In order to reestablish right relationship with the land that my great-grandmother gifted me, I knew I needed to understand more about the history of the place and the people that shaped me. And I knew that there was one person who could help me find my way through our family’s history of placemaking. That person was our kin keeper and family historian, my great-aunt Lydia Whitley. She is the eldest daughter of my great-grandmother Doris, a teacher, advisor, and inspiration to our family as we organize to settle our heirs’ property challenges and to bring to life some of the dreams that we have to make the land a place of remembering and reconnection. With only an iPad and microphone on hand, we sat in her kitchen on a humid summer day for a conversation rooted in ancestral wisdom (the past), deep reflection (the present), and radical imagination (the future).

QUAY WESTON: So, can you explain how we ended up in Riddick Town, how our family purchased the land, or any of the things you remember?

LYDIA WHITLEY: Okay. From my understanding, I don’t have any idea where Mama and Daddy [Annie and Noah, Aunt Lydia’s maternal grandparents] were staying prior to staying in Riddick Town. When I became of age, we were living in Chocowinity. Chocowinity is about fifteen minutes southwest of Washington, North Carolina. Right across the Pamlico River bridge. When we lived in Chocowinity, Daddy was already doing sharecropping. Then, I found out later when we moved back to Pantego, I think it was 1955 or 1956, that they were owners of the land that we call Riddick Town before they even went to Chocowinity. This land was up for sale, and he got it from who Mama and them—the way they pronounced it was “Mr. Calvin,” but we found out that it’s Carawan. It’s spelled C-a-r-a-w-a-n. And then we moved to Grimesland, which was the last place that I remember that we lived as sharecroppers. And those were hard times, hearing my grandmother and everybody talk about it. Me, as a child, I didn’t know that we would’ve been considered poor, because we had everything. We always had fall, winter, and summer gardens so we always had food on the table. We had a milk cow to bring in milk for clabber, butter, and everything. We had rows of corn. Daddy would take the corn to the grist mill and have the corn ground up. We didn’t have to buy lard or grease because we had pigs and would use the skins. There was always food on the table! And my grandmama was a seamstress, so we never worried about clothes. I wore some of the prettiest dresses! In fact, she [Annie] made most of the dresses, jackets, skirts, underskirts (now called slips), and blouses that the women in the family wore. They were mostly made from flour bags. She would buy as many as she needed for a particular garment and saved them to keep the exact color and design that she wanted. We had everything we needed right there on the land. So, to me, I wasn’t poor, I was rich!

As we dove deeper into the history of our family and their beginnings in Riddick Town, Aunt Lydia continued to talk me through some of the lean years of living in such a rural area. She explained the ways that our family would make meals from plain fatback meat, fried, and dressed with gravy. She also introduced me to what they called “skippers,” small hovering insects that would crowd around barrels of salted meat in their smokehouse. Though times were hard, there was a cooperative way of life that brought together all generations that lived on the land.

LW: Those were happy times, Quay; it kept the family together. My uncles went in the garden, they picked the beans and harvested whatever it was. And we all sat down on the front porch, and we shelled the beans. Those were such happy times, Quay! But you know how [Riddick Town] got its name?

QW: No, actually, I don’t.

LW: People used to come visit all the time because of the love that they received from the family! Our cousin Marie Walker, from Philadelphia, visited one year and she said, “Y’all ought to name it Riddick Town or Riddickville or something. But put your mark on it, because all Riddicks live up here.” We had our own community there. We were pretty much self-sufficient. And all around Pantego, there are little roads and what we call towns like this that are named after the majority family that lives there. I believe it’s a way to identify the families or to know who lives where. So, eventually, the county put up a road sign for Riddick Road. So, it started to be called Riddick Town. That’s what we called it.

QW: I never knew that. Wow. Wow.

As you might imagine, I was soaking in all of this new information. Hearing her describe the communalism and connection to the land—and especially the fact that she never really knew that our family was poor because everyone had what they needed—is exactly how I describe my childhood. To see that experience transfer in that way, especially in the way that we tell the story of our family making a way out of no way, was heartwarming. As she detailed even more of our family history to me, I guided us to a question that would help me understand what the land used to look and feel like.

QW: Could you paint me a picture of what Riddick Town looked like, visually? What was it like?

LW: Okay. To the outsider, you know, nobody wanted to stay in those sticks. We were away from everybody else. Isolated. But, as a child—all I know is peace and joy. I didn’t like being teased a bit about being in the sticks. ’Cause people made comments, like, I guess we were supposed to be different from everybody else. It was very lonesome. But [the land] was clear between Berlie and Daddy’s houses, and there was a big ditch. We dared to jump that ditch! You could’ve fallen in it. That’s just how wide it was. But, when it would rain, the water in that ditch was beautiful. We used to dip water from that ditch to wash in, to wash our clothes and everything. So, all of that [about fifteen acres] behind those six houses was cleared land and that was what we called the pasture. It’s where the cows and pigs and horses were kept before Daddy let all of them out; we used to play softball, baseball, whatever kind of ball it was back there. My granddaddy was a farmer, and those are some of my best memories, how he would take that mule and that plow—and you know how far it is from the ditch and the road—to all the way back! That land was cleared, believe it or not! And he had us going behind that mule and I’m stepping every step, right behind him. And he even taught me how to keep that plow in that soil, oh, those were happy times! And I think as Daddy got older, by then he was not able to tend the land, and my three uncles, Gerald, Aulander, and Cleophus built their homes on the land, you can see from the street today how the family has stopped maintaining the land. And that is really sad.

Aunt Lydia had anticipated my next question. Although the plan was to talk about the past, present, and future of the land, I was so moved by the prestigious history of our family that I wanted to stay there for a little while longer. It felt easier to discuss all the happy times. But I knew that we would get here eventually. Today, as younger generations (including myself) seek social mobility and work in industries outside of agriculture and manufacturing, stewardship and physical connection to the land have been lost. Trees and vegetation have regrown, covering most of the backyards of every home. Besides one portion of the property that is leased to a local farmer, the land is no longer clear for agricultural use. The ditch that Aunt Lydia mentioned, which was once filled with crystal clear water, no longer exists. Four of the five homes on the land are in need of major renovations. The ancestors buried on the land lie in unmarked graves down unclear paths. Over time, unwanted items, irreparable cars, and trash have been piled up on the land rather than transported to local waste sites. It seemed as if all of this came to mind for Aunt Lydia, as she spoke before I could utter the question.

QW: How do you feel about the state that the land is in today—

LW: [interjects] It is very hurtful. Because it’s been neglected. And you would have to have seen it through my eyes, to know what it feels like now to just go up there. And I’m like, your granddaddy worked hard, or your daddy worked hard for this land. And I never understood it. I guess, evidently, you got to have a love for something to tend to it. And so, by the factories coming at that time and the family having to make a living a different way, we started working and everything. My uncle Charlie (Chock), he was a lover of the land. And he tried with all his heart. Unfortunately, we were not able to purchase our own farm equipment, but he always worked on the farm all his life. So, as I said, we don’t have ditches anymore. Which, as you know, when the rain comes, here’s the flooding. Things have just been piled up; you see old cars. Everything that nobody wanted, trash, has been dumped on the land. So, it’s going to take a lot to clear. And I would just love to see that. But if I don’t, I pray to God, your generation will get to see what Riddick Town can be.

One of the hardest parts of this moment was just how it felt hearing her explain what it was like to witness the changes over the decades. There was a tangible (and audible) disappointment and hurt that I could feel from Aunt Lydia as she reflected on the neglect of this place that was so special to her and instrumental to the survival of our family. Instead of trying to move on to avoid the heaviness of the moment, I asked her what she believes it would take to bring back the love that our family had for this land in years past.

QW: So, what do you think it would take for the younger generation of our family to recover the love that, it sounds like, your generation had for the land?

LW: Perhaps, if they could hear the story, the sacrifice, that was made to get it. That land was hard gotten. Nobody put it in my grandaddy’s lap. They worked hard. Again, this was my grandmother’s reason for leaving home months at the time to do this migrant work, picking oranges, broccoli, anything; the grapes right in Plymouth, North Carolina. Anything that needed to be done. And she always sent money back to take care of the land. And Lawyer John Wilkinson, one of my grandaddy’s childhood friends, who became a very prominent lawyer, asked my grandaddy, he said, “Noah, why don’t you just sell the land?” and Daddy said, “No, John. I want to leave the youngins something.” In the word of God, it tells us that we are to leave our children an inheritance. Now that inheritance could be money, land, could be a family legacy, or whatever. I don’t know what they meant, but if we had been able to keep that place up, then your generation could be making a fine living off that land. So, when I see it right now, I know it’s gonna take bookoodles of money, it’s gonna take cooperation on the part of the family to come together to get somebody in there that knows what they’re doing. It’s a lot of land and it shouldn’t go to waste. It shouldn’t go to waste. Because Daddy and Mama worked hard to preserve that. To leave it to the children. And their children’s children, and their children.

As Aunt Lydia poured more and more into me, I knew that I did not want us to leave our conversation feeling defeated or intimidated by the collective work that is before us. As she recalled memories that led us to deep belly laughter, it was clear to me that our family could handle hard things; our conversation proved that we always have. After sitting, breathing, and feeling our way through the hard conversation about the current state of the land, I wanted to leave Aunt Lydia with a question that would call forth her imagination for new and radical possibilities.

QW: So, my last question is, what would you like to see? If we had the money we needed, the equipment, the resources, all of that. What do you imagine Riddick Town could be?

LW: My God! [laughs] Wow. Sometimes when things are right in front of you, it’s kind of hard to rise above, to see what it could be. But I know that it could be great. I would love to see cleared land! Without all the debris, without all these old cars and junk, just clear! And for the miles that it could go. I would love to see crops grow again. I would love to see that communal garden. I would love to see all the houses restored that need to be restored. Ditches so that there won’t be flooding. Beautiful yards! I’d love to see everybody keep their yard clean. Family coming together, having reunions, having picnics, whatever. I just love family, next to God. Family is everything to me. And I would just love to see us come together and make this thing happen.

We have been called to do just that. Along with this grounding conversation, Aunt Lydia and I have been co-organizing our family members to dream, vision, and strategize on what our home place could be—to re-imagine Riddick Town as a place to uplift Black southern futures. Our goal is to dream of new possibilities for the descendants of the Riddick family. We draw from the courage and wisdom of our ancestors to be in right relationship with the land, which will allow us to collectively heal, restore, and reconnect to Riddick Town. Riddick Town, we will do right by you.

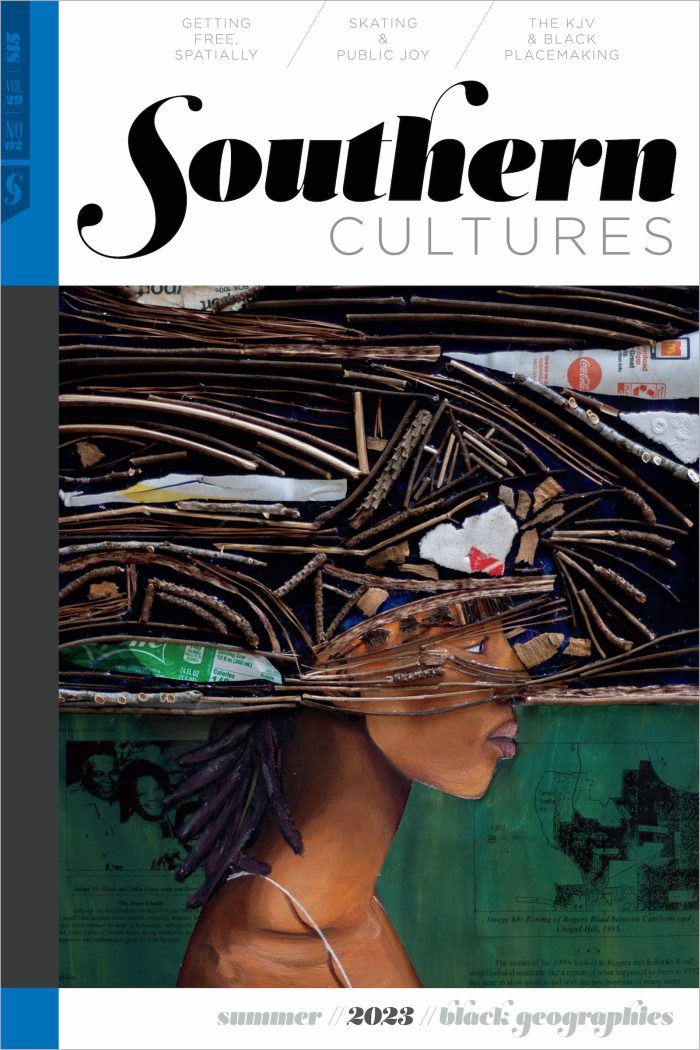

This essay was first published in the Black Geographies issue (vol 29, no. 2: Summer 2023).

Quay Weston is a Black southern designer, author, and family archivist from Pantego, North Carolina. With over a decade of experience as a design professional, Quay uses his creative talents to support local and national organizations that are committed to building a more equitable and just world.

NOTES

- “Census of Population and Housing,” Census.gov, 2020.

- Leah Douglas, “African Americans Have Lost Untold Acres of Farmland over the Last Century,” Food & Environment Reporting Network, June 26, 2017, https://thefern.org/2017/06/african-americans-lost-untold-acres-farmland-last-century/.