“Senior year, be good to me!” announced Mahoghany Jordan, a fourth-year general studies major at the University of Mississippi (UM), in a September 17, 2018 Facebook post. In the two images accompanying her post, an exuberant Jordan poses in the Square, the central business and entertainment hub of Oxford, Mississippi, home of the UM campus. She had no idea that passersby also snapped photos of her and her friend Ki’yona Crawford. Those images clocked thousands of views after Ed Meek, namesake of UM’s Meek School of Journalism and New Media, included them in his own Facebook post urging “Oxford and Ole Miss leaders” to “get on top of this before it’s too late.” “This” included declining university enrollment at UM and rising crime rates, falling property values, and diminishing tax revenue in Oxford. He ended the post with a call “to protect the values we hold dear.”1

Meek tapped into a centuries-old vernacular that marked Black women’s bodies as symbols of social disorder. And many who read and responded to Meek’s post agreed. Several hundred people liked, commented on, and shared his post within their own social networks. Some of those reposts (since removed) lamented the loss of the Square’s “family-friendly” atmosphere.

Others likened the Square to a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah. For these Oxonians, it seemed Black women’s bodies did more than signify impending peril; they embodied it. Black women’s bodies operated not merely as symbols of social decline but also as the personification of the moral decay eroding the quality of life in (white) Oxonians’ beloved town. Their comments shed light on ongoing disputes about race and space in a town and campus infused with Confederate memory and Lost Cause iconography. In particular, they amplify contentious questions about who has legitimate rights to occupy public spaces and to interpret their meanings.2

In response to the Meek affair, the journalism school denounced its primary donor and namesake’s remarks, saying they “violated the fundamental values of the school and the university,” and it pressed Meek to request that his name be removed from the school. Faculty, staff, and students mobilized through protests, open letters, petitions, and a teach-in to nominate Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s name as a replacement. Born enslaved in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, about a half hour north of Oxford, Ida Belle Wells-Barnett stands as one of the most outstanding women of the twentieth century. A journalist, anti-lynching advocate, suffragist, activist, and progressive theorist, she called out injustice and then urged Americans to resist oppression. Her diary, pamphlets, speeches, and other writings reflect the private and public struggles of a professional woman to define womanhood in a pivotal era of US history. A reformer who insisted on economic and political justice, Wells-Barnett helped lay the foundations for both the modern civil rights and women’s movements and shaped the post-Reconstruction discourse on social justice.3

Ida Belle Wells-Barnett stands as one of the most outstanding women of the twentieth century.

Wells-Barnett’s name was among the short list of names suggested to grace the journalism school. For supporters, her status as a daughter of Mississippi made her a stronger choice than other candidates, such as the French-British journalist Paul Guihard, who was mysteriously shot and murdered on campus during the 1962 Ole Miss Riot. Wells-Barnett’s journalistic legacy would also signal a progressive departure from UM’s reputation as an insular, white space. Her incisive critique of state power and insistent calls for equity still galvanize a broad range of activists today, from those decrying police shootings and violence against unarmed Black men and women to prison abolitionists to political campaign funding reform. Even as contemporary activists draw inspiration from her groundbreaking work in Memphis and Chicago, they are often unaware of the inspiration Wells-Barnett drew from the community of freedpeople in Reconstruction-era North Mississippi.4

Wells-Barnett’s activism is often imagined sui generis, springing from a unique individual who transcended her place, circumstance, and community to become a woman historian Paula Giddings heralds as “a sword among lions.” To be sure, Wells-Barnett was an exceptional woman. It is important, though, as we center the experiences of Black women like Wells-Barnett, that we also chip away at well-meaning shibboleths that place her outside of the political culture that shaped her democratic vision and activism. Wells-Barnett was emblematic of, rather than an exception to, her community. Freedpeople made Butts Alley and the Bone Yard, neighborhoods in Holly Springs, strongholds of Black community and courage. These spaces kindled young Ida’s political consciousness and determination to take on a railroad corporation, lynching, suffrage, the carceral state, and other causes later in her life. From parochial debates about renaming UM’s J-school to national celebrations of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, our contemporary moment begs for a reassessment of the wider origins—and places—of women’s activism.5

Wells-Barnett was emblematic of, rather than an exception to, her community.

In the early 1800s, Mississippi attracted whites, mostly from the Upper South, looking to make their fortunes. In only a few years after removal of the Indigenous Chickasaw in 1832, Marshall County emerged as a cultural and economic hub in northern Mississippi. By 1850, the county was the largest cotton producer in the state and Holly Springs, the county seat, reflected the region’s riches. Some of the wealthiest and largest enslavers in Mississippi lived in the town. Scores of grand and small antebellum mansions blanketed Holly Springs, and some of the state’s largest plantations dotted the rural hinterland. The town’s opulence and wealth rested on the labor and bodies of the enslaved. On the eve of the Civil War, the US census counted 17,439 enslaved people, eight free Blacks, and 11,376 whites in Marshall County, ranking its per capita slave population fourth highest in the state and twentieth highest in the nation. During the war, the county’s Black population soared as Black southerners left farms and plantations to seek refuge behind Union lines. A Union general described “negroes coming in by wagon loads.” After the war, Freedmen’s Bureau officials noted twenty-two thousand freedpeople living in the Holly Springs subdistrict. The deprivations of war made their conditions very bleak, yet Black people in Holly Springs reconstituted their families, carved out distinct neighborhoods, and created their own institutions. Black political culture in Holly Springs reflected contests over households, space, work, and politics between freedpeople and the smaller white population.6

Assumptions about liberal and democratic political traditions in the United States shift when we center Black political culture. Drawing attention away from the formal ballot as the primary expression of political engagement, we look instead toward a range of practices and meanings that complicate what is considered “political.” As political actors with the power to pursue individual and collective empowerment, Black communities turned to multiple arenas of political engagement within and outside of formal political processes and structures. The household, streets, schools, churches, and fields joined the courthouse and town square as sites of civic engagement. Political actors, which included women and children, engaged a broad range of material and symbolic resources to guide their participation in public life, including religion, kinship, memories, work life, and more. Black communities did not act from—or even in—consensus, nor did they uncritically share the same values, beliefs, and goals. The Black community was no monolith. Nonetheless, Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s private and public communities deeply influenced her activism, and the Black community of Holly Springs wielded significant political power through and beyond the ballot box.7

Politics of the Household

Wells-Barnett’s parents were her first teachers. In 1867, when she was about five years old, her parents James “Jim” Wells and Elizabeth “Lizzie” (also “Liza”) Wells gave their former master Spires Boling a lesson that they were no longer his enslaved apprentice and cook but free people who would do as they pleased.8

Technically, Jim Wells had never even “belonged” to Spires Boling. Wells grew up with his enslaved mother and siblings on Morgan Wells’s plantation in Tippah County, east of Marshall County. In 1860, Morgan, Jim Wells’s enslaver and father, apprenticed his nineteen-year-old son to Boling, a carpenter who arrived in Holly Springs in the late 1840s. Within a decade, Boling earned a reputation as a master builder. When Morgan died, Wells remained the property of Morgan’s widow while she continued to hire him out to Boling. The community certainly understood that Jim belonged to Boling in name if not fact. Boling must have enjoyed his good fortune as young Wells proved a very fine carpenter and fell in love and took up with Lizzie, the Bolings’ enslaved cook. Their relationship provided a source of solace in a time of flux.9

After the Civil War, Boling insisted that the Wellses remain on the property. But the Wells couple performed their own calculus in deciding to stay. They were among many newly freed-people determined to manage their own labor. In withdrawing women and children from the fields and kitchens of white families, freedpeople sought to live beyond the surveillance and control of their former enslavers. And receiving neither remuneration for generations of toil nor land upon which to build new lives, the decisions they made about their families represented an assertion of their liberty.

Black and white struggles over the meaning of freedom were particularly acute in urban settings like Holly Springs. For generations, Black men and women lived in close quarters with their enslavers. Stately mansions dotted Holly Springs’s landscape and some enslavers also built well-appointed dwellings for the people they enslaved, a few in full view to passersby and neighbors, that reflected enslavers’ preoccupation with wealth and status. In addition to fine quarters for enslaved people, well-to-do enslavers sometimes provided nice clothing for house servants and even taught some to read in public defiance of state law and social custom. With Emancipation, former enslavers suffered heavy blows financially and socially in losing both the emblems and substance of their wealth.

The heaviest blow to white power may have been losing all semblance of control over Black people’s decisions about how they would conduct their lives, constitute and manage their families, and earn their livings, and now the newest blow: vote according to their consciences. Southern white enslavement of Blacks, it turns out, had cultivated generations of white dependence. In an emancipated social order, whites feared losing control of a political system expressly designed for their interests. With passage of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, Black men across the United States—including northern freedpeople who had seen their civil rights stripped throughout the nineteenth century—seized their political rights as legal citizens and voted in unprecedented numbers in the 1867 elections. Blacks in Marshall County outnumbered whites by about six thousand souls. Their incredible electoral power was not lost on either side.10

It was in this context of white fears of Black suffrage that Spires Boling demanded Jim Wells vote the Democratic ticket. Wells voted Republican. An incensed Boling calculated the most effective reprimand: He locked up Wells’s workshop and tools to intimidate the young man into submission. However, when Wells found his workshop locked, he promptly went to town and bought a new set of tools. By the time Boling returned home, smug that his lesson had hit home, he discovered that Wells had already packed up his family and left. This story reveals a great deal about not only Jim Wells but also Black political culture in the aftermath of the Civil War, a culture that would shape Ida Wells-Barnett’s radical imagination. Black communities claimed their freedom, expressed their political and social autonomy, and faced resistance from the old guard.11

Economic repression was a powerful tool whites used to check Black freedoms. Sharecropping and crop lien arrangements insidiously re-enslaved Black people to the land and their former enslavers, who remained its owners. Exploitative labor contracts were less effective with skilled artisans, who exercised an appreciable measure of autonomy, even during slavery. Boling had not anticipated that Wells had been saving money since his enslavement. Lizzie Wells, a skilled cook, also contributed her financial savvy to build up the family’s wealth. The Wells’s savings endowed them with an extra measure of freedom to resist the demands of their former enslaver and invest in their daughter’s future.

Not everyone had savings like the Wellses or the economic autonomy to defy insistent former masters and mistresses. In her father’s example and in the examples of those less fortunate than her parents, a young Ida Belle came to understand the linkages between economic exploitation and repression. She saw how whites tried to control Black people’s working lives as a tool to undermine their democratic freedoms. Later in her life, these lessons helped her to see the hypocrisy in the “threadbare lie” of Black male sexual predation of white women. Her anti-lynching crusade uncovered the economic underpinnings of racialized sexual violence.12

Black Political Culture and the Civic Geography of Reconstruction-Era North Mississippi

Like most freedpeople in Holly Springs, Jim and Lizzie Wells became politically active. Jim joined the Loyal League, also called the Union League. Republican Party supporters, Black and white, first organized Loyal Leagues during the Civil War to support the Union cause. While whites often led these clubs, Blacks filled other leadership positions and made up most of the rank and file. The Loyal League grew into the largest Black political organization in the South. Hundreds of leagues sprung up across Mississippi after 1867. Exact numbers are not known, but a Jackson newspaper, the Daily Clarion, noted that most Black voters were members of Loyal Leagues. Jim’s local club may have been organized by Albert C. McDonald, a Methodist missionary and later president of Shaw University, later renamed Rust College, or Nelson Gill, a white Union veteran, both from Illinois. In Loyal Leagues, freedpeople acquired basic civic lessons from the Constitution, kept informed about candidates running for public office, and learned how to cast ballots.13

Foreseeing resistance, the Loyal League matched political competence with self-defense. When violence erupted across Mississippi between armed Black men, many of whom were League members, and whites, the state’s provisional governor William Lewis Sharkey disbanded the Leagues in 1865, judging armed Black men a provocation that incited whites to violence rather than seeing the members’ actions as self-defense against already violent whites. In unequivocal language, the 1868 Democratic Executive Committee called on whites to maintain “eternal vigilance” and accused Blacks in Loyal Leagues of perpetrating “fearful crime[s] against themselves and the superior race on which they depend for all that is valuable in life.” The white press resorted to scare tactics, warning freedpeople in the Daily Clarion of the penalties that would befall Loyal League participants: “a punishment of two years in the Penitentiary, a heavy fine and loss of suffrage for life.” Threats to Loyal Leagues only propelled Black militancy and commitment to pursue democratic freedoms.14

Though only men were counted in official membership numbers, women were active in the Loyal Leagues. Black women hosted political meetings not only in their own homes but in the homes of their white employers. They attended political rallies, voiced their opinions about candidates and issues, campaigned and raised money for candidates, monitored polling places, and counted ballots. It is not a stretch to assume that wives accompanied their newly elected husbands to the capitol in Jackson or stood among the audiences in the galleries of the state capitol, as they did across the South.15

Black women wore badges for Republican contenders in defiance of their white employers and overseers. Their boldness was not without consequences. Some employers fired cooks and housekeepers when they discovered the women were politically active. An angry white farmer threw Black sharecroppers Eliza Brunson and her husband Bedny off of his land after he discovered the couple cast votes in Holly Springs. Whites also boycotted skilled artisans, including women, who openly expressed support for the Republican Party.16

Ida B. Wells-Barnett: Crusader for Justice

Not all freedpeople were able to escape resentful former owners—or resist a tempting offer. For instance, Marshall County Democrats gifted a home to Henry House, a Black Democrat, in appreciation of his “faithfulness and services” to the party cause. House helped form and led the Colored Democratic Club in Holly Springs. When it came to their own communities, however, Black Democrats often faced public censure and backlash, with Black women leading the charge. They ridiculed and shunned men who voted the Democratic ticket. Historian Steven Hahn captures the life-and-death implications of Black women as enforcers of the community’s norms: “In a kin-oriented world in which subsistence was precarious and white patrons quixotic, social isolation could be a devastating, and potentially lethal, sentence in its own right.” In 1875, a particularly bloody election year in which Democrats replaced every Republican candidate throughout the state, a Mississippi newspaper felt it noteworthy to highlight that 250 Black men presented verified ballots cast for the Democratic ticket. Vigilante groups made up of former Confederate soldiers and citizens lynched, killed, and drove out of the state hundreds of Blacks and whites who supported Reconstruction. Given these perils, some Black voters understandably cast their lot with the Democrats.17

Freedpeople connected with one another through organized barbecues, rallies, and parades that built social and political networks. A Freedmen’s Bureau agent in Mississippi observed that freedpeople would travel as much as twenty-five miles to attend political gatherings. At barbecues and rallies, former enslavers and their allies wooed Black North Mississippians with eloquent speeches, urging them to vote the Democratic ticket with promises to return to the harmony of the antebellum years. Blacks, however, saw through the Democrats’ hypocrisy. Freedpeople debated the merits of various platforms and political hopefuls during their own barbecues and rallies. In 1869, Holly Springs hosted a political rally in the town’s central square. An estimated four thousand Blacks attended.18

Women were trusted links between their hometown of Holly Springs and the state capitol two hundred miles away in Jackson. As both messengers and interpreters, they reported firsthand accounts to their communities of the debates and political bustle they witnessed. Women engaged in and sometimes spoke in lively political debates. Combined with their other political activities, such as raising money and participating in parades, some whites considered, according to historian Elsa Barkley Brown, these “unorthodox political engagements to be signs of [Blacks’] unfamiliarity and perhaps unreadiness for politics.” Whites remarked negatively on the presence of Black women at political rallies, political meetings, and polling places, pointing to women’s presence as a prime example of Blacks’ unfitness for full citizenship.19

Beyond rallies and meetings, parades were a particularly democratic expression of political will that called for the cooperation of individuals and families across multiple communities. Wells-Barnett’s mother and her mother’s friends likely spent hours preparing for these parades. Enlisting the help of their children, women sewed red sashes, oilcloth wheel hats with feathers, large blue and red badges, and colorful banners. They helped construct floats and transparencies, which were thin banners stretched across a frame and illuminated from behind by lamps. They painted signs, some as wide as twelve feet, with caricatures of Democratic opponents, including local white candidates.20

A young Ida Belle may have witnessed one significant political parade in Holly Springs, though she does not mention it in her autobiography. Thousands of Blacks from around the county formed a procession that stretched more than a mile long. Some rode horses but most walked, creating a sea of red sashes indicating their support for Republican candidates running for office. Former soldiers marched in formation with their freshly oiled and polished weapons at their sides while drummers beat out the time and played patriotic songs, all proudly donning their Union blues. One white woman recalled a particularly terrifying float with a tree stump studded with branches and hung with possums. A “big negro” sat on the stump singing, “Carve that possum, nigger, carve him to the heart. Carve that white man, nigger, carve him to the heart.” Torchlights and impressive transparencies glowed in the night and could be seen from miles away. Demonstrations liberated Blacks, if only for a few hours, from the humiliating racial etiquette that increasingly regulated their behavior in public spaces. Parades and political rallies showcased Blacks as a viable and active constituency, with even nonvoters—women and children—exercising a meaningful political role beyond the narrow ballot.21

Blacks mapped a deliberate and strategic civic geography in parades as they proceeded through predominantly Black areas like Butts Alley, near present-day Rust College, and the Bone Yard, near Asbury Church. They also wound through the main thoroughfares and majority white neighborhoods of Holly Springs. Marchers made stops at Democratic candidates’ stately homes and mansions, most of which still stand today. Bolder members of the group yelled and cursed at the candidates; some even threw rocks. Whites answered these powerful civic displays with parades of their own and tighter physical and economic repression. Violence often met even small parades. Newspaper headlines framed Black parades and processions as an “armed angry mob,” an “army of bloodthirsty, ignorant Blacks,” and other dangerous monikers that stoked whites’ fears and justified retaliatory violence against Black men, women, and children.22

The physical and symbolic reclamation of space—from attending rallies to participating in parades—proved particularly poignant in this post-Emancipation moment when so much of African Americans’ visions of freedom, particularly owning their own land and freely exercising their citizenship rights, had been left unrealized. Most freedpeople did not receive land at the end of their long decades of servitude, but the demonstrators staked a claim on the places they had enriched with their labor—perhaps even built with their own hands.

Black men and women staked claims in other ways, such as through financial and legal channels. Women fought for Civil War widows’ pensions and survivors’ benefits. Wells-Barnett’s paternal grandmother Peggy Wells filed for her son David’s pension. Black women enlisted witnesses and gathered legal documents, such as marriage licenses, affidavits, and powers of attorney, for federal pension board investigators to affirm their rights to inherit, to equal consideration, and to reparative justice.23

Freedpeople also used the Freedmen’s Bureau courts to achieve some justice for themselves. Blacks reclaimed family members bound to white families and sued former white employers for unpaid wages and shares. Some whites justified their indenture of Blacks using the draconian apprenticeship laws passed in the state in 1865. These laws only allowed whites to become legal guardians of orphaned Black children and young adults. In exchange for room and board, these young people worked for the white families without pay for a contractual period—typically until they reached adulthood. In reality, many of these youth were not orphans and had close or extended family members willing to take them in and care for them. But whites justified indenturing Black workers based on their long-accustomed sense of racial entitlement. For example, former enslaver Wesley Ward in nearby Water Valley threatened to kill George Oscar if he stepped foot on Ward’s land. In the chaos of war, Oscar and his wife Roseanna had been separated. He learned that Roseanna had been working on Ward’s farm and went to retrieve her from Ward and reunite her with their family in Holly Springs. It took a Freedman’s Bureau official ordering Ward to release Roseanna and do no harm to George for the couple to be together again. Officials also ordered another white Holly Springs resident to return the little girl Polly Halbone to her mother. Blacks often used the Freedmen’s Bureau to help them extract their loved ones from indentures and labor contracts that emerged as new forms of quasi-slavery.24

Blacks also turned to the Freedmen’s Bureau to help them assert their financial rights. They sued tightfisted employers and planters who cheated them out of their pay. Whites so resented orders to bring their account books to Freedmen’s Bureau offices that military officials had to threaten to send armed soldiers if defendants did not appear at their scheduled times. The courts directed whites to pay money, livestock, cotton, and foodstuffs to freedpeople they had swindled. Black women like Emily Faulk proved particularly adept at using the Bureau courts. In one month, she prevailed in two cases: one against Richard Hampton for five dollars in unpaid wages and another against Pompey King for three dollars.25

The Freedmen’s Bureau courts addressed only a fraction of the fraud perpetrated against freedpeople. The Bureau, too, could be a fickle ally. In some cases, the Holly Springs District Freedmen’s Bureau court ruled against Black plaintiffs and defendants, upholding apprenticeship of Black children to whites and ordering Blacks to give up their share or accept less money for their crops. The Bureau refused to take an accurate census of elderly and infirm Blacks in the subdistrict, which affected the amount of rations the community received. Stretched thin in resources and personnel, the Bureau could do little to address violence against freedpeople. Once disbanded by Congress in 1872, freedpeople lost even the Bureau’s modest protections.26

Black Political Culture and Armed Self-Defense

One of Wells-Barnett’s most cherished memories involved reading the newspaper to her father and his friends. She read aloud national and local stories of retaliation against Blacks seeking their rights. She recalled, “I heard the words Ku Klux Klan long before I knew what they meant.” By the 1870s, Mississippians determined to redeem the state during the period historians refer to as Redemption—a time when whites used the law, economic repression, and extralegal violence to reinstitute white supremacy, purge Republican Party influence, and turn back the tide on Black progress. They marked Redemption in blood. In places like Vicksburg, Yazoo City, Clinton, and Oxford, the tactics ranged from fraud, intimidation, kidnapping, driving tenants and farmers from the land, beatings, and lynching. Women and children counted among the hundreds lynched. In nearby Lafayette County, the Ku Klux Klan killed seventeen to thirty Black men and women and then threw their bodies into the Yocona River. Throughout Mississippi, armed whites searched at night for Loyal League meetings, and Wells-Barnett vividly recalled her mother pacing the floor many nights when her father was out attending Loyal League meetings. Lizzie Wells paced because she knew such violence was not unheard of in Holly Springs.27

Holly Springs boasted at least ten and perhaps as many as fifteen KKK dens, as local groups were called. The KKK targeted Republicans, Black and white. As in other places, the Holly Springs KKK included some of the town’s most prominent men, many of them former enslavers. Holly Springs Klan members dressed in black-and-red disguises then descended on Black neighborhoods in meticulously coordinated raids and stole any weapons they could find to prevent Black self-defense. They beat unarmed Blacks they judged insolent and threatened to lynch Blacks who prevailed in cases against whites in the Freedmen’s Bureau courts. Two men tried to assassinate Nelson Gill during a Loyal League meeting at his home. They planned to kill him in front of the Blacks in attendance to send a pointed message.28

Amid such despotism, Wells-Barnett witnessed both humble and impressive displays of Black resistance. She heard Blacks use formal titles—such as “Mr.” and “Mrs.”—when addressing each other and drop such honorifics when talking to whites. Such linguistic rebellion was a small but significant way Blacks raised intraracial pride and challenged a South doubling down on its commitment to white supremacy. Wells-Barnett’s father likely joined the Black men who formed armed pickets outside of league meetings after Gill’s attempted assassination. Women also may have helped arm the pickets, as they did in other parts of the South. More important, young Ida heard stories of Blacks seeking justice through armed self-defense. In 1870, in Mount Pleasant, a town in Marshall County fourteen miles northwest of Holly Springs, a group of about twenty Black men marched into town demanding prosecution of a white man who had wounded a Black man in an argument. The following year, in Starkville, Blacks banded together and armed themselves to effect the release of Blacks held in jail for what the group considered unjustified charges. In 1874, in Tunica, an armed conflict broke out between whites and Blacks after Blacks banded together, marched into the county seat, and demanded that the white murderer of a Black girl be returned to jail.29

Indiscriminate violence loomed, especially at the polls. One strategy for collective protection included going to the polls early and in large numbers. Black men marched to polling places in groups of a hundred or more. Black women and children, too, went to voting booths by the hundreds. Some walked, mounted horses and mules, or rode in wagons. In Monroe County, also in North Mississippi, Democrats shot up a church where women and children gathered before walking together to cast their votes. Black women, then, faced considerable physical risk and even death because of their political activities.30

Indeed, Black women confronted a range of racial and gender-based repercussions for their political activism. In addition to economic backlash, Democrats often accused Republican candidates and Freedmen’s Bureau officials of having sexual relationships with Black women to discredit their political rivals. In Holly Springs, rumors that the “carpetbagger” Nelson Gill’s wife was actually a mixed-race woman were calculated to smear his name. White women in particular criticized Black women’s public political activities as a way to mark differences between their own proper womanhood and Black women’s unwomanly behavior. Historian Thavolia Glymph emphasizes these attacks as “one kind of evidence of the different ambitions and notions of citizenship” held by Black and white women. Negative assertions of Black womanhood represented one important way for whites to claim the moral high ground and denounce Black autonomy as a disruption of the natural order. Many whites in North Mississippi felt the need to crush Black economic and political autonomy to reestablish the foundation of white privilege that rested on laying claims to Black bodies, labor, and spaces.31

It was in this mix of triumph and repression, opportunity and threat, that a young Ida absorbed the lessons of a diverse Black public sphere in which women played an active role and elevated their voices. She looked to Black-led institutions and the needs of Black communities as sources of inspiration and leadership for developing a broad, progressive agenda. She learned that economic exploitation, extralegal racial and sexual violence, and state-sanctioned harassment often threatened Black political expression and economic sovereignty. She would learn other lessons, too, as she became a young woman. Indeed, she gained from her early lessons the courage to use her voice and pen to crusade for justice.

Wells-Barnett’s youth was tragically cut short. At sixteen years old, both of her parents and a sibling died during the 1878 yellow fever epidemic. She stepped up to support her remaining five siblings, lying about her age so that she could take the teacher’s certification exam. She began teaching in rural Marshall County, at first riding a mule and then later taking trains to travel to her teaching job from Memphis to Woodstock, Tennessee. She had moved to Memphis a couple of years before she was ejected from the first-class ladies’ car in 1883. In 1884, she sued the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwestern Railway. She began her career as a journalist writing about her lawsuit and local issues under the pen name “Iola.” She was co-owner of the Memphis Free Speech, where she launched her anti-lynching columns in 1892. There, she spoke out against the lynching of a close friend and two other men, setting the stage for a lifelong pursuit of truth. Lifting the veil on white supremacist strictures nearly cost Wells-Barnett her life; she was forced to leave Memphis amid death threats. A pioneer in the field, she toured Great Britain to promote one of journalism’s earliest investigative exposés: her 1895 book The Red Record, which linked the racial, gendered, and economic underpinnings of lynching and state-sanctioned violence. It was for her courageous reporting of lynchings in the United States that she was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize this year. Wells-Barnett’s legacy continues in organizations she founded or helped cofound that are still active today, including the National Association of Colored Women (1896), the NAACP (1909), and the Alpha Suffrage Club (1913).

In 2019, Jodi Skipper, Shennette Garrett-Scott, and Beth Kruse applied for and received a University of Mississippi Community Wellbeing Constellation Grant (UMCWGG) to support the research phase for the creation of an Ida B. Wells Commemorative Tour (IBWCT). The tour would cover Wells-Barnett’s early life in Holly Springs and use the existing landscape to tell more inclusive public history narratives. Kruse, a doctoral candidate in the Arch Dalrymple III Department of History, served as the primary graduate student researcher. Baylee Champion, an undergraduate at Rust College, served as a student assistant. Rhondalyn K. Peairs, a graduate student in the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and founder of HISTORICH, a tourism and educational services company, helped guide the pilot tour in November 2019.32

The objective of the UMCWCG is to improve community well-being through collective engagement and the integration of various academic areas of expertise and specialization. The grant criteria specified that the project be based on partnership with and have a wider impact on the specified community. The grant was announced in late 2018, only two months after Ed Meek’s Facebook post, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett was on our minds. Although recognition of Wells-Barnett’s legacy in her birthplace has grown in recent years, our lived experiences as educators and researchers in North Mississippi made real her relative absence on Mississippi’s contemporary landscape. Thus, the idea for the tour came on the heels of responses to Meek’s post, as well as a realization of how the Meek incident touched on ways that the past connected with the contemporary moment.33

Mahoghany and Ki’yona, the two UM students pictured in Meek’s derisive post, were also on our minds. The two young women, as sociologist Barbara Harris Combs argues, were “perceived as ‘dissonant bodies’” in the Oxford Square: “Some bodies are deemed as having the right to belong, while others are marked out as trespasser, who are, in accordance with how both spaces and bodies are imagined (politically, historically and conceptually), circumscribed as being ‘out of place.’” Wells-Barnett and the Black community that shaped her, in some ways, also had been cast as out of place. The tour project presented opportunities to reduce the dissonance by addressing issues of equity, fairness, and social justice. As communities engage racist pasts, the concept of community well-being invites alternative strategies not only to address “contemporary divisions, racial inequities, and minority disempowerment” but also to reduce conflict and build relationships. Seeking to extend beyond facile efforts to repair relationships, the IBWCT endeavors to interpret spaces in ways that address both structural inequities that silence racially underrepresented groups and address the traumatic legacies of slavery. Anthropologist Jodi Skipper states that recovering the Black political culture that shaped Wells-Barnett demands “representing difficult pasts in the present . . . [through] consistent, therapeutic community work, which acknowledges those traumas.” The IBWCT brings fresh perspectives to the historical silences and the contemporary challenges that confront not only North Mississippi but the nation.34

Few would argue that Wells-Barnett was not an outstanding woman, although we are still reckoning with her legacy and the full measure of her accomplishments. Much of what she would go on to realize was made possible not merely because of her own considerable personal merits, but also because she drew from the strength of her community as a whole, and especially from special networks of talented Black women.

This article was first published in the Women’s Issue (vol. 26, no. 3: Fall 2020).

Beth Kruse is a PhD candidate at the University of Mississippi. Her research focus is Civil War memory and military prisons. She examines survival techniques of Black and white prisoners of war and the women who aided them.

Rhondalyn K. Peairs is a master’s candidate in southern studies at the University of Mississippi. Her previous and current research focuses on the resiliency and agency of African American landowners in Mississippi and, more specifically, the Mississippi Hill Country. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, an iconic Hill Country native, has been central to that research for over twenty years.

Jodi Skipper is an associate professor of anthropology and southern studies at the University of Mississippi. She researches how historic preservation projects can help create healthier futures for southern communities. She is the coeditor (with Michele Grigsby Coffey) of Navigating Souths: Transdisciplinary Explorations of a U.S. Region (University of Georgia Press, 2017).

Shennette Garrett-Scott is an associate professor of history and African American studies at the University of Mississippi. She is the author of the award-winning Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal, published by Columbia University Press in 2019. Follow her on Twitter at @EbonRebel.NOTES

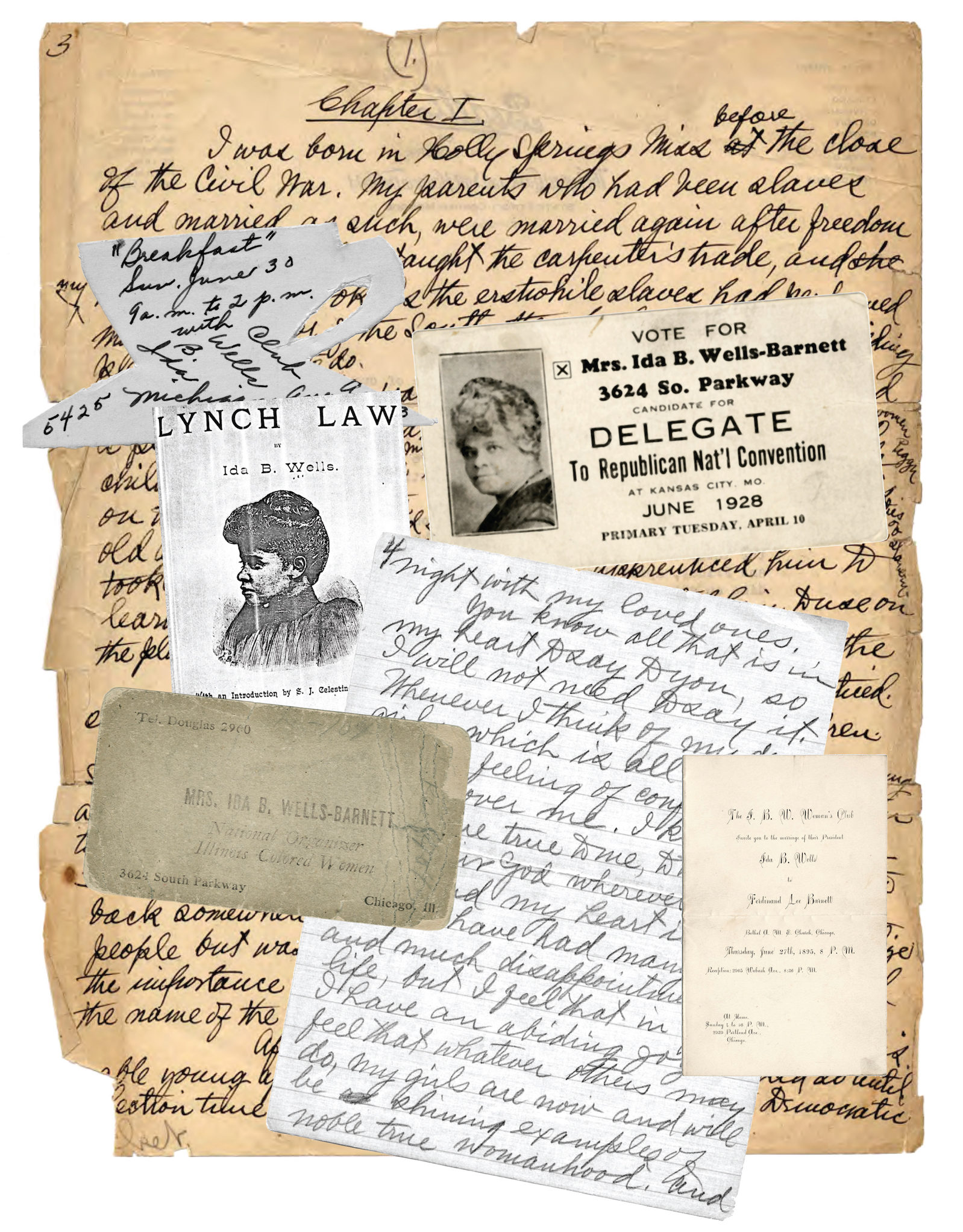

Collage image includes: Handwritten chapter of Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells; campaign card for Wells-Barnett, candidate for delegate to the 1928 Republican National Convention in Kansas City, Missouri; teacup-shaped invitation for Ida B. Wells Woman’s Club breakfast; title page of Wells-Barnett’s Lynch Law; Wells-Barnett’s 1920 letter to daughters Ida and Alfreda; Wells-Barnett’s calling card as national organizer for Illinois Colored Women; Wells-Barnett and Ferdinand Barnett’s 1895 wedding invitation. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

- Mahoghany Jordan, “Senior Year, Be Good to Me!,” Facebook, September 17, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/mj.jordaa/posts/1318523671615495. Meek’s post has since been removed, but news outlets circulated screenshots. For example, see Shante Sumpter, “Ole Miss Students Speak Out about Ed Meek Post,” WTVA, updated September 24, 2018, https://www.wtva.com/content/video/493920181.html.

- Barbara Harris Combs, “Black (and Brown) Bodies Out of Place: Towards a Theoretical Understanding of Systematic Voter Suppression in the United States,” Critical Sociology 42, no. 4/5 (2016): 535–549; Nirmal Puwar, Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place (London: Berg, 2004). For the racial demographics of the University of Mississippi and Oxford, see the University of Mississippi, “2018–2019 Mini Fact Book,” The University of Mississippi Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning, accessed April 14, 2020, https://irep.olemiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/98/2019/03/Mini-Fact-Book_2018-2019.pdf; and “QuickFacts Oxford City, Mississippi,” United States Census Bureau, accessed April 14, 2020, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/oxfordcitymississippi.

- Quote in Dean Will Norton Jr.’s video statement, “Dr. Norton Response,” Daily Journal, September 20, 2018, https://www.djournal.com/dr-norton-response/video_e3f0227e-0b90-5eaf-a278-5c341c60fcf5.html; Emily Wagster Pettus, “Facebook Post Sparks Call to Rename Ole Miss Journalism School for Ida B. Wells-Barnett,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 2018, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-ole-miss-journalism-school-ida-b-wells-20181006-story.html; Shennette Garrett-Scott, “#UpWithIda Campaign Challenges the University of Mississippi to Celebrate a True Rebel,” Association of Black Women Historians, April 4, 2019, http://abwh.org/2019/04/04/upwithida-campaign-challenges-the-university-of-mississippi-to-celebrate-a-true-rebel/; James West Davidson, “They Say”: Ida B. Wells and the Reconstruction of Race (Oxford University Press, 2007); Mia Bay, “‘If Iola Were a Man’: Gender, Jim Crow and Public Protest in the Work of Ida B. Wells,” in Becoming Visible: Women’s Presence in Late Nineteenth-Century America, ed. Janet Floyd, Alison Easton, R. J. Ellis, and Lindsey Traub (Leiden, NLD: Brill, 2010), 105–128.

- Keisha N. Blain, “Ida B. Wells Offered the Solution to Police Violence More than 100 Years Ago,” Washington Post, July 11, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2017/07/11/ida-b-wells-offered-the-solution-to-police-violence-more-than-100-years-ago/; William Calathes, “Racial Capitalism and Punishment Philosophy and Practices: What Really Stands in the Way of Prison Abolition,” Contemporary Justice Review 20, no. 4 (2017): 442–455; Ida’s Legacy, Ida B. Wells Legacy Committee, accessed April 17, 2020, https://idaslegacy.com/.

- Paula J. Giddings, Ida: A Sword Among Lions; Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching (New York: HarperCollins, 2008). For a quick but insightful overview of the linkages between historical memory, collective memory, and the politics of memory, see Katherine Hite, “Historical Memory,” in International Encyclopedia of Political Science, ed. Bertrand Badie, Dirk Berg-Schlosser, and Leonardo Morlino (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2011), 1079–1082. Wells-Barnett sued the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwest Railroad in 1884. The train conductor, baggageman, and two white male passengers forcibly removed her from her seat in the ladies car and threw her onto the pavement. She prevailed in her lawsuit, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned her $500 lawsuit on appeal.

- Brandon H. Beck, Holly Springs: Van Dorn, the CSS Arkansas and the Raid that Saved Vicksburg (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011), quote on 62 and demographic figures on 54; Jodi Skipper, “Community Development through Reconciliation Tourism: The Behind the Big House Program in Holly Springs, Mississippi,” Community Development 47, no. 4 (2016): 519–520; “Marshall County, Mississippi: Largest Slaveholders from 1860 Slave Census Schedules and Surname Matches for African Americans on 1870 Census,” transcribed by Tom Blake, RootsWeb, February 2002, https://sites.rootsweb.com/~ajac/msmarshall.htm; “Table I. Owners of Slaves and Numbers Owned in 1860” in Ruth Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society, vol. 12, 1910–1911, ed. Franklin L. Riley ([Oxford?]: University of Mississippi, 1912), 208; Reports, John Powers to Merritt Barber, November 14, 1867, in Mississippi Freedmen’s Bureau Office Records, 1865–1872, Holly Springs (Subassistant Commissioner) (hereafter cited as Mississippi Freedmen’s Bureau Office Records), roll 19 [Letters Sent, September 1867–December 1868], frame 6; “General Superintendent of Contrabands in the Department of the Tennessee to the Headquarters of the Department, April 29, 1863,” in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867, series 1, vol. 3: The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Lower South, ed. René Hayden, Anthony E. Kaye, Kate Masur, Steven F. Miller, Susan E. O’Donovan, Leslie S. Rowland, and Stephen A. West (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 690–695.

- The works invoking theories of political culture are vast and extend across disciplines. Here, we are most influenced by Gabriel A. Almond and Sidney Verba, The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (1963; repr., Princeton University Press, 2016); Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989); Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power, ed. John B. Thompson, trans. Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991); Stephanie McCurry, Masters of Small Worlds: Yeoman Households, Gender Relations, and the Political Culture of the Antebellum South Carolina Low Country (Oxford University Press, 1995); and Laura F. Edwards, Gendered Strife and Confusion: The Political Culture of Reconstruction (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997). Examples of work on southern Black women’s political culture during the mid to late nineteenth century include Elsa Barkley Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom,” Public Culture 7 (1994): 107–146; Steven Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South, from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005); Martha S. Jones, All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830–1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), esp. part 2, “A State of Mobilization: Politics in Arkansas, 1865–1868”; and Mary Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen and the Freedmen’s Bureau: Race, Gender, and Public Policy in the Age of Emancipation (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010).

- Wells-Barnett’s daughter and editor of her mother’s autobiography Alfreda M. Duster writes that A. J. Wells, Wells-Barnett’s brother, stated that Lizzie’s maiden name is Warrenton. Biographer Paula Giddings believes Lizzie’s maiden name is Arrington, taken from her first enslaver William Arrington of Appomattox County, Virginia. On the Arrington surname, see Giddings, Sword Among Lions, 16. For details about Wells-Barnett’s life in Holly Springs, see Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells, ed. Alfreda M. Duster (University of Chicago Press, 1970), xiv–xvi, 1–20, 7n3; Linda O. McMurry, To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B. Wells (Oxford University Press, 1998), 3–17; Giddings, Sword Among Lions, 15–39; Mia Bay, To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells (New York: Hill and Wang, 2009), 15–39; and Davidson, “They Say,” 1, 13–17, 46.

- On taking up, sweethearting, and other relationships enslaved and freedpeople pursued outside of legal marriages, see Noralee Frankel, Freedom’s Women: Black Women and Families in Civil War Era Mississippi (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999); Nancy Bercaw, Gendered Freedoms: Race, Rights, and the Politics of Household in the Delta, 1861–1875 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003); Tera W. Hunter, Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017).

- The civil rights of Blacks in the North had been steadily eroded through the nineteenth century, with many municipalities and states disenfranchising African American voters. After the Civil War and after passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, the numbers of Black voters in the South, of course, increased exponentially as formerly enslaved men cast votes, but the numbers of Black male voters also swelled in the North. See Jeffrey A. Mullins, “Race, Place and African-American Disenfranchisement in the Early Nineteenth-Century American North,” Citizenship Studies 10, no. 1 (2006): 77–91. Population figures from Appendix B, “Table 2. [Marshall County] Population Statistics, 1860–1880” in Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 208.

- Duster, Crusade for Justice, 8; McMurry, To Keep the Waters Troubled, 9; Giddings, Sword Among Lions, 26; Bay, To Tell the Truth Freely, 20; Davidson, “They Say,” 24.

- Megan Ming Francis, “Ida B. Wells and the Economics of Racial Violence,” Social Science Research Council, January 24, 2017, https://items.ssrc.org/reading-racial-conflict/ida-b-wells-and-the-economics-of-racial-violence/; Bay, “‘If Iola Were a Man.’”

- By 1863, more than four thousand leagues claimed a membership of seven hundred thousand. The numbers increased exponentially after the war. Leagues formed throughout Marshall County in Holly Springs, Red Banks, Byhalia, Tallaloosa, and Chulahoma. McDonald helped organize one of the first formal churches for Blacks and became the first president of Rust College. Gill served as the Holly Springs postmaster and led the regional Freedman’s Bureau office headquartered in downtown Holly Springs. Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 165, 171; Michael W. Fitzgerald, The Union League Movement in the Deep South: Politics and Agricultural Change during Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1989), 25, 56, 59; Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet, 177–189; “To the Colored Voters of Jackson Precinct,” Daily Clarion (Jackson, MS), June 26, 1868.

- Reprinted in “Mississippi,” Appletons’ Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events […], vol. 8 (1868) (New York: D. Appleton, 1869), 513; “The Address to Freedmen: Read and Circulate,” Daily Clarion (Jackson, MS), June 13, 1868, 2, emphasis in original.

- Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet, 185, 202, 227; Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere,” 110.

- John Powers to S. C. Green, July 8, 1868, Mississippi Freedmen’s Bureau Office Records, roll 20, Miscellaneous Records, Sep 1867–Dec 1868, frames 12–13; 1870 U.S. Census, Bed Brunson Record, Dwelling Number 777, Township 5 Range 4, Marshall, Mississippi, page 459B, https://familyse-arch.org; Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet, 228; Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere,” 110.

- Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet, 227, 229–230; Herald (Vicksburg, MS), November 3, 1875, quoted in Wharton Vernon Lane, The Negro in Mississippi, 1865–1890 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947; repr., New York: Harper Torchlight, 1965), 195; Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere,” 110; Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 224, 225. House’s enslaver James J. House made a fortune during the war as a Confederate blockade runner. House may have shrewdly calculated the economic benefits of aligning with his former master’s interest. Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 165. On James House, see Phillip Knecht, “Grey Gables (1848),” Hill Country History, accessed May 18, 2020, https://hillcountryhistory.org/2015/12/03/holly-springs-grey-gables-1848/.

- Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet, 214; “Out of Darkness Cometh Light,” Weekly Louisianan (New Orleans, LA), August 17, 1871, 2; Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage, 218–219; Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 189.

- Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere,” 110.

- Descriptions of the parades in Holly Springs from Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 177, 185–187; Lane, The Negro in Mississippi, 166.

- Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 186. Watkins does not state what year the parade took place. For references to Blacks’ political parades, especially with Loyal Leagues in other Mississippi towns, see “Testimony of M. H. Whitaker, June 29, 1871,” 171 (Meridian); “Testimony of John R. Taliaferro, July 15, 1871,” 234 (Brooksville); “Testimony of James H. Rives, November 7, 1871,” 569 (Macon), all in US Congress, Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Mississippi vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1872).

- Quotes from “Columbus, Mississippi. Terrible Negro Riots […],” Daily Appeal (Memphis, TN), October 26, 1871, 1; “Mississippi […],” Daily Appeal (Memphis, TN), October 6, 1875, 1. On violence at Black parades in Mississippi, see “Testimony of M. H. Whitaker”; “Testimony of John R. Taliaferro”; and “Testimony of James H. Rives.” One working definition of civic geography is a space that compels inhabitants to think and act collectively, imparting “an obligation to be civic, to make and to defend connections in such a way that transcends narrow self-interest.” Chris Philo, Kye Askins, and Ian Cook, “Civic Geographies: Pictures and Other Things at an Exhibition,” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 14, no. 2 (January 2015): 360. The meaning and boundaries of that geography, as well as who constitutes its legitimate inhabitants, inform our discussion. Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere,” 109; Mary P. Ryan, “Gender and Public Sphere: Women’s Politics in Nineteenth-Century America,” in Habermas and the Public Sphere, ed. Craig J. Calhoun (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 259–278, esp. 252–273; Jones, All Bound Up Together; Stephanie McCurry, Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010). While Ryan effectively argues how women spun a distinctly private sphere apart from the democratic public sphere, others have shown how women helped mesh the two supposedly separate spheres together.

- Michelle A. Krowl, “‘Her Just Dues’: Civil War Pensions of African American Women in Virginia,” in Negotiating Boundaries of Southern Womanhood: Dealing with the Powers that Be, ed. Janet L. Coryell, Thomas H. Appleton Jr., Anastatia Sims, and Sandra Gioia Treadway (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000), 52–74; Brandi C. Brimmer, “Black Women’s Politics, Narratives of Sexual Immorality, and Pension Bureaucracy in Mary Lee’s North Carolina Neighborhood,” Journal of Southern History 80, no. 4 (November, 2014): 827–858; Bercaw, Gendered Freedoms; Frankel, Freedom’s Women.

- Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen and the Freedmen’s Bureau, 113; John Powers to Wesley Ward, September 21, 1867 (frame 4) and Powers to J. C. Davis, November 13, 1867 (frame 5), roll 19, Mississippi Freedmen’s Bureau Office Records.

- Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen and the Freedmen’s Bureau, 141; Powers to Wm. Lankers [?], November 8, 1867 (frame 5) and “Report of Complaints for Month Ending Dec 31, 1867” (frames 20–22) in roll 19, and Powers to Benj. O. Johnson, August 4, 1868, frame 15, roll 20, Mississippi Freedmen’s Bureau Office Records.

- See rolls 19 and 20, Mississippi Freedmen’s Bureau Office Records.

- Duster, Crusade for Justice, 9; Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 177; Bercaw, Gendered Freedoms, 162–163, 170–171; Lane, The Negro in Mississippi, 194–195, 198–202; Fitzgerald, Union League Movement, 59.

- The attacks on Gill’s life did not end. Locals raised five hundred dollars to hire a man from Texas to kill Gill, but they reneged at the last minute. Future Memphis political boss Edward Hull Crump headed a KKK den in his hometown of Holly Springs. Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 169, 172, 178–179, 179n60; Lane, The Negro in Mississippi, 164–166, 165n34.

- Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage, 218–219; Hahn, A Nation under Our Feet, 227; “Mississippi,” Weekly Clarion (Jackson, MS), August 25, 1870, 1; “The Starkville Riot,” Weekly Clarion (Jackson, MS), December 14, 1871, 2; “The Tunica War!!!,” Weekly Clarion (Jackson, MS), August 27, 1874, 1; George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (1984; repr., Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007), 147. Also see “The Trouble Between the Plundering Officials and the Warren County Tax-Payers,” Weekly Clarion (Jackson, MS), December 17, 1874, 3.

- Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 186–187, 189; Lane, The Negro in Mississippi, 145, 166; “Hazelhurst, June 28, 1868,” Daily Clarion (Jackson, MS), July 1, 1868, 2; Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere,” 109. For testimonies about violence in Mississippi, see US Congress, Joint Select Committee on the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, part 3: Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas (Washington, DC: General Printing Office, 1866).

- Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage, 224; Watkins, “Reconstruction in Marshall County,” 169; Bercaw, Gendered Freedoms, 133. On gendered racial violence, see Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom; and Williams, They Left Great Marks on Me.

- Skipper, “Community Development”; Barbara H. Combs, Kirsten Dellinger, Jeffrey T. Jackson, Kirk A. Johnson, Willa M. Johnson, Jodi Skipper, John Sonnett, James M. Thomas, and Critical Race Studies Group, “The Symbolic Lynching of James Meredith: A Visual Analysis and Collective Counter Narrative to Racial Domination,” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2, no. 3 (2016): 338–353.

- In addition to the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum, a local post office in Holly Springs is named in her honor. In July 2019, the Jewish-American Society for Historic Preservation donated a historical marker for Wells-Barnett in the Holly Springs Square. In November 2019, a Mississippi Writers Trail marker was added to the Rust College campus in her honor.

- Combs, “Black (and Brown) Bodies Out of Place,” 536; Skipper, “Community Development,” 514, 515. Also see Behind the Big House, accessed April 18, 2020, https://behindthebighouse.org/.