My grandparents’ house on Hardup Road in Albany, Georgia, was my first understanding of sanctuary. Our house was not in Albany proper; we lived past the city limits in Dougherty County. Planting and grazing fields flanked us on three sides of our yard. And each trip “in town” was a mini-quest: my Paw Paw Eugene’s booming voice would announce, “We going to town today,” and we’d nod and get dressed and “ret to go,” because going into the city was an all-day adventure. It was too damn hot outside, for the most part, to sit on the porch when I’d visit in the summers, but we made our exodus from the house to the porch swing and rocking chairs when the sun decided we’d had enough. The screech of the swing was a welcome sound as I snuggled into Nana’s armpit and listened to the silence of country life. At my grandparents’ house, I didn’t have the weight of being the oldest child on my shoulders. I didn’t have to fight my siblings for the tv or attention. My grandparents’ house was my escape. It was my place of rest and recharging.

The bricks of our house were painted to complement the red and white painted shutters. The front of the house in theory was not the front of the house in practice—we used the side door next to the covered carport. Our side porch was our gathering place: the metal swing and rocking chairs painted green, and, later, white, was my favorite place in the yard. Paw Paw was hellbent on building the house from scratch. It was not lost on my folks, raised and coming of age in the heat of the Jim Crow South, that Black people weren’t expected to qualify for anything financial, let alone a mortgage for a house with land. But my folks were mythbreakers, and that is exactly what they did. Their previous house, a cute little cottage on Robinson Avenue, in Albany, was on the corner and everyone knew that the Barnetts lived there and worked hard to keep it. My grandparents worked primarily as educators but had multiple side jobs to get what they needed to get by. They saved, fussed, and scraped their money together to build their dream. “I remember trying to rub two nickels together to get a quarter,” Nana Boo said one time when reminding me about the benefits of hard work. She and Paw Paw imagined the Hardup Roadhouse to be grand—brick and mortar, with four bedrooms, a sprawling front and backyard, garage, and a basement. This was their dream, to move their family to place that didn’t buzz with the uncertain aftermath of the (then) recent failures of civil rights unrest and protests in Albany.

After fighting with the bank, my grandparents were approved for a loan to buy land and construction supplies for their dreamhouse. Ever the hustler and grinder, Paw Paw worked as a teacher, owned a gas station, and was a traveling referee for football and basketball games. He was also a skilled mason like his daddy and worked on the house on the weekends. My Paw Paw didn’t like to be “up under nobody,” meaning he was his own man and expected to be in charge of his own fate. Paw Paw laid the foundation of the house with his hands and set up the house frame before hurting his back while working on it. His injury prevented him from completing the house, but rest assured he surveilled every step of the process. Our house didn’t get the basement, but we got everything else. The house was completed in 1972, eleven years after the beginning of the Albany Civil Rights Movement, with my Daddy, Reginald, in 10th grade and my Auntie Deidre in middle school. Even though the house was in the country, it was the hotspot for parties and get togethers for Daddy and his friends. Cars full of teenagers—and sometimes their parents—would rumble down the gravel driveway. The garage was repurposed into a game room, and Daddy and his friends would listen to Funk music, talk shit, and laugh under the watchful eye of my Nana, who brought them sodas and snacks from the kitchen. Daddy’s social life was poppin’. He was popular, handsome, and the life of the party. The way he told it, his friends loved coming to his house. It gave them some time away from their own lives.

My friends? They sucked their teeth and rolled their eyes when it was my turn to host our get togethers. My friends didn’t see the splendor of driving down our unpaved driveway or hearing the popping of small bits of concrete and rocks to welcome them to our big-ass house to kick it. My friends were economical and shared their concerns about the costs of being in my circle.

“You live waaaaay the hell out there, Gina,” they said while throwing their arm due south and violently pointing in the direction of my house. “Just getting to your house eats up all my gas and I see you ain’t putting in on the tank!”

When I formally presented their complaint to Nana (still holding strong as the director of social services and catering at our house), she scoffed and waved me away like a commoner. “Well, are they really your friends if they won’t come see you at your house like you go see them?”

Even though my home wasn’t their sanctuary, my cost-conscious teenage friends still (grudgingly) made the trek to Hardup Road, careful to turn down the volume about a mile away from the house because a thrumming subwoofer wasn’t a proper announcement of their arrival and Nana didn’t play that. Pushing past my smirking face at the side door and hugging Nana’s neck to say hello, they presented themselves as properly home trained and we watched movies and kicked it in the game room, laughing and talking shit like my Daddy and his friends decades before.

For this issue of Southern Cultures, we wanted to engage the South’s complicated relationship with sanctuary. Executed under the careful guidance of guest editor Annette M. Rodríguez, our “Sanctuary” issue grapples with the complexities of the South as a place of refuge and possibility. From “places to sigh” to “otherwise possibilities,” these essays, reflections, and creative works speak to sanctuary in its many forms, demonstrating resistance, resilience, and community, and the ways in which they overlap.

Seldom viewed as a place of reprieve, the region is often depicted in the popular imagination as being without protections, inhospitable, monstrous, “sick,” a place to escape from, especially for Black folks. But a place of historical, cultural, and economic prejudices, where bigotry and intolerance is renewed and re-visited enough to become finely polished touchstones of southern life with each generation, is also home to freedom dreams and hard-won refuge. Spaces of rest and care were carved out in defiance in a land where happiness, culture, and rooted identities were long considered “whites only”—a warning and a disinvitation, like the signs that populated the region during Jim Crow. But joy, expression, and heritage belong to all of us, the manifestations of countless people who made their home on these lands, who made their communities, churches, and homes places of welcome and refuge, against all odds.

Even now, in an increasingly tense social climate where America is again showing its racial slip, people are still searching for refuge and peace in the South, and people are still fighting to provide it. The border crisis, voter suppression, health disparities, climate change, the movement and legislation to ban Critical Race Theory (crt)—all are rooted here, with reactionaries and resisters both. White folks did some foul stuff in the past and are doing some foul stuff in the present that will be felt well into the future. The privilege to turn a blind eye is as dazzling as looking straight into the sun.

Sanctuary-building is a generational act of labor, my folks’ house on Hardup Road being but one small example. Asylum-as-labor is grounded in an urgent need to not only create a physically non-threatening space but establish an interior sense of safety and purpose as well. From this perspective, memory is the longstanding foundation of not only southernness but the cultural landscape it produces. Memory frames any understanding of southern agency, often collapsed into nostalgia for things that may or may not have happened. The South-as-Confederacy is the most glaring example of this type of collapse, its reality being a trove of white supremacist apologists but the descendants of the Confederacy holding its memory dear as a beacon of resistance of radical change.

This issue grounds representations of sanctuary as constant acts of revision. We need to revisit how the creation of art establishes respite. We need to revisit how humanity exists outside of a white gaze. We need to revisit how communal building—the cornerstone of sanctuary—constantly pulls itself up and breaks apart when shifted from action to reflection. We need to revisit the politicization of and corporate intervention into safe spaces that were created to express freedoms and rights denied elsewhere. It is our hope that this issue places readers squarely in the middle of a sanctuary from which to engage these difficult questions and take notes on why the South is indeed hallowed ground where refuge is hard-earned and hard-remembered.

This essay first appeared in the Sanctuary Issue (vol. 28, no. 2: Summer 2022).

Regina N. Bradley is a writer and researcher of the Black American South. A former Nasir Jones HipHop Fellow at the Hutchins Center, Harvard University, she is associate professor of English and African diaspora studies at Kennesaw State University and coeditor of Southern Cultures. Dr. Bradley is the author of Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South. She can be reached at redclayscholar.com.

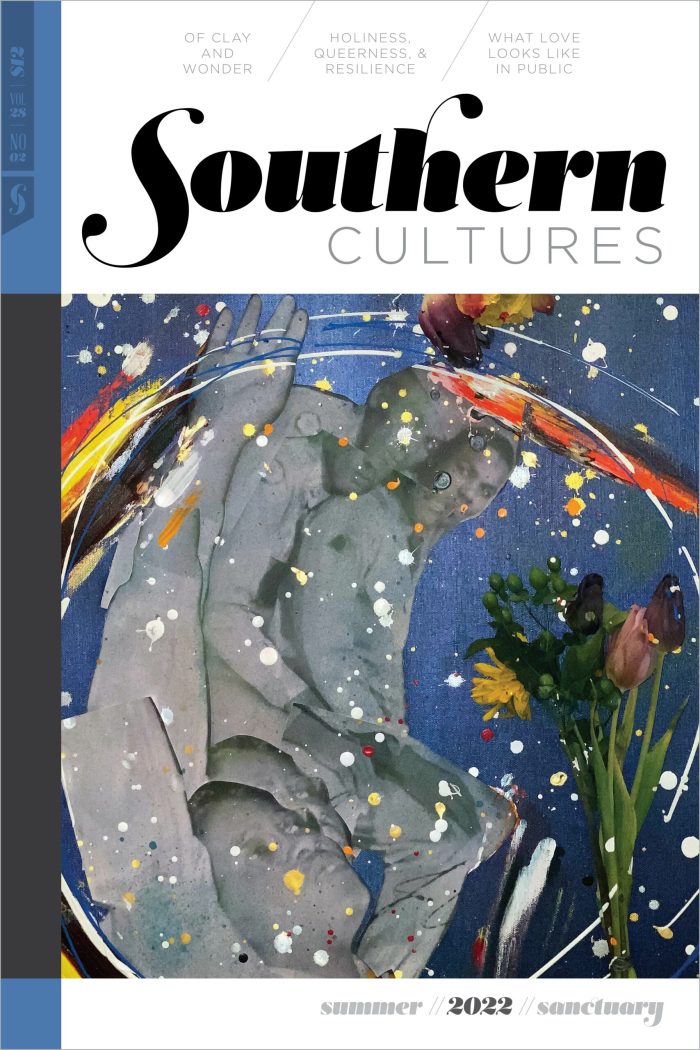

Header Image: Ashon Crawley i did not not know i could be beautiful (number 7), 2021. Acrylic paint, acrylic ink, polyester film, pigment powder, dyed hymns on watercolor paper, 30 × 44 in.