In advance of two special issues, Regina N. Bradley and Charles Hughes caught up to discuss the hip-hop South and the many ways that their varied interests intersect—from hip-hop histories and futures to riffing and representation. Those issues are now available: The Sonic South (Spring 2022), guest edited by Bradley, and Disability (Spring 2023), guest edited by Hughes.

Regina N. Bradley: One of the things that brings us together is southern hip hop. So you are originally from Wisconsin?

Charles Hughes: Yeah.

RNB: I’m going to ask you like I used to ask on OutKasted Conversations. How did you first get into southern hip hop?

CH: It’s hard to point to one thing. I mean, I definitely grew up right at the moment when southern hip hop became nationally recognized. I was a little too young for the 2 Live Crew, early Geto Boys era. And then over those next few years, I just started recognizing that there was this thing that was coming out of the South . . . that I really was responding to. It was really Atlanta that really got me. I mean, OutKast and Goodie Mob were the things that really hooked me in, which I don’t think was a coincidence. As you write about, it was remixing and riffing off of some sonic traditions that I was into and that kind of stuff.

But by the early 2000s, I mean, the entire center of hip hop commercially and creatively was in the South. It was Missy and Timbaland, and the Neptunes were the northern end of hip hop at this point. There were a few years where I feel like 90%, at least of the newer hip hop that I listened to, was all Atlanta or Houston or Memphis or New Orleans or Kentucky, like Nappy Roots.

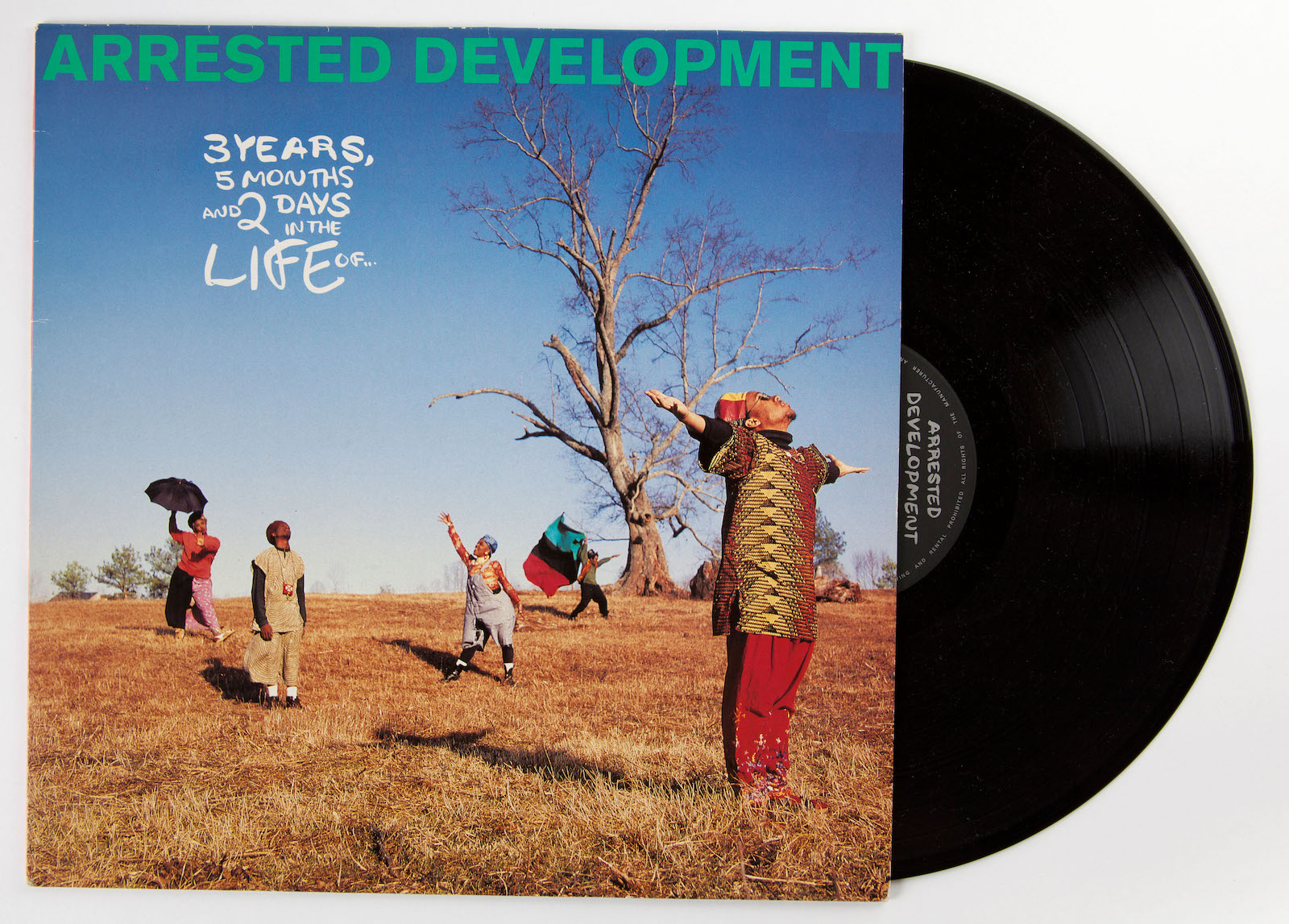

I do think Arrested Development was so important in the way in which people who were not from these places or who were a little younger were introduced. In some ways, that became a strange introduction. But in other ways, I was just listening to 3 Years [5 Months and 2 Days in the Life Of…] and I was just struck by how they were really tapping into something that I think a lot of other artists would then build off of in interesting ways. That was definitely an important one for me.

RNB: I always think it’s interesting that Arrested Development plays such a part of it. It took me a long time to realize that they are from Atlanta because when I was growing up, I heard the “Tennessee” song.

CH: They were from Tennessee?

RNB: I just assumed they were from Tennessee (laughs). I think that’s really interesting with a lot of the acts out of Atlanta in the early 90s that came out, there wasn’t an intentional situating or centering of Atlanta itself. And that didn’t really happen.

Another thing that’s interesting, you mentioned the Nappy Roots. I’m waiting for somebody to have this conversation because you have the Nappy Roots talking about a particular type of rural, southern experience. They were my first introduction to Anthony Hamilton, too. It’s interesting that they’re actually talking about a particular experience in poverty that’s rooted, honest, and, in some ways, refreshing. And then you hear songs like “Tennessee” that have this almost Bohemian vibe, like, “Oh, this is what it means to be rural in the South.”

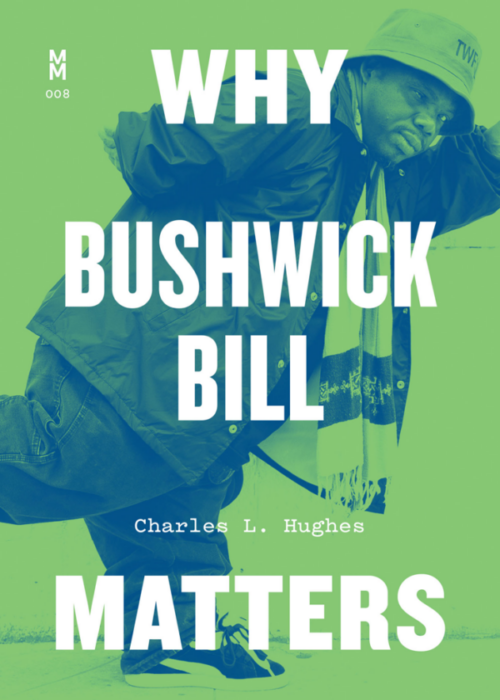

I’m curious how they’re in conversation with each other. But one of the things I wanted to talk to you about, aside from your initial southernness is, I loved your book Why Bushwick Bill Matters. I mean, I loved it so much that I blurbed it. So, what was it about Bushwick Bill, and then a particular angle of disability, that you were like, “Yep, this has to be talked about now.”

CH: I had long thought about Bill. Because, well, first of all, the Geto Boys are great. I don’t think they’re anywhere near getting the appreciation that they deserve, even with Scarface being recognized as such an incredible, important force.

Those Geto Boys records still sound amazing. And they’re so much more interesting than people who don’t really listen to them, and then write about them or write them off, give them credit for. That early 90s stretch of records they had was so great. I obviously plugged into Bill early on in part because of our shared physicality and the way that he talked about it. And the way that he talked about being short. And he talked about other things as well, obviously. That wasn’t the only reason why I was into his stuff. But I just found that so bracing.

So I always had that personal relationship, which is interesting because one of the many things that I think is so powerful about your work is how you are also framing around a memoir. Or incorporating. You’re not making it all about you, but you’re clearly putting yourself in this world, as you should. I think that’s something that a lot of my favorite hip-hop scholarship does in some way or another. So I was thinking a lot about that. Then yeah, with the Pop Conference, which is such an incredible space that we have both been very involved with over the years, I was asked to put together this panel with a couple old friends. I think the theme of the conference that year was Sex and Sexuality or something like that. So I thought, “Well, maybe this is the time to do this thing I wanted to do about Bushwick Bill, and sex, and shortness, and disability.”

There is this way in which he challenges our understandings of what it means to be disabled. He uses this particular kind of hip-hop masculinity and hip-hop oratory, rhetoric, and sound. He uses that and performs it to challenge these conceptions, while he’s also trying to negotiate particularly gangsta spaces. So I wanted to play with that. And I realized as I was writing—I mean, to be just perfectly real about it: I’m going to show up in that room for the conference. People are going to see how tall I am or I’m not. And if I don’t acknowledge this, it’s going to be weird.

I also realized beyond that, “No, no, no. This is a time where I want to talk about this.” Reading a lot of disability studies scholarship and also knowing how in a variety of scholarly traditions, including in hip-hop scholarship, memoir or a personal infusing can be so important, that’s why I did it. I never thought I would write a whole book about it. I thought I’d do my 15 minutes at the Pop Conference and that would be it.

But yeah, I mean, it was loving Bushwick Bill’s records, finding his stuff incredibly powerful as it related to shortness and disability. Putting him in some context that I didn’t think he was in. And then realizing as I was doing it that I was getting a chance to talk about some things personally but more importantly, historically, that had not been talked about. It also goes back to the fact that ultimately, I just think the Geto Boys are great. And I think Bushwick Bill is great. That’s another thing I love about your work, is that you talk so brilliantly as a critic and a fan.

How do you approach that? Because I think you do it so well that sometimes it almost doesn’t announce itself as being the deeply fan-based but critical love for them and listening that you do.

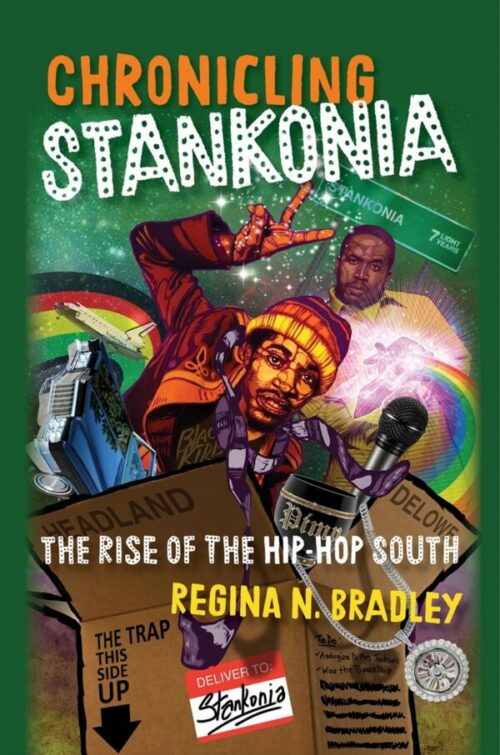

RNB: It’s actually interesting that you asked me that because the very first piece of OutKast anything that I wrote was actually in 2011 for the Sounding Out! blog. Even then, it wasn’t necessarily a more personal experience based essay. But when I started doing OutKasted Conversations, I started really thinking about that personal connection, a lot in part because of that first conversation that I had with Kiese [Laymon]. When I actually started writing Chronicling Stankonia, I was like, “What are some of the major moments of OutKastedness, so to speak, that I had and wanted to expand upon?”

Another part of my writing process for that book was trying to reclaim the part of myself that I had been trained to remove from my academic work. But it was even in the ways that folks were talking about hip hop: the marginalization is always there. As somebody from the South, I wasn’t the focal point. I wasn’t the point of interest for thinking about what the significance of hip-hop culture was. That gave me space.

I also looked to scholars who didn’t shy away from including themselves in the work. Mark Anthony Neal remains a huge inspiration for my scholarship. He showed his audience multiple times in his own big-ass body of work that situating the personal as a critical side of inquiry is useful and hella fruitful. I think the challenge though is making sure that I don’t overly share so that it doesn’t take away from the criticism. I am constantly searching for the balance in sharing enough that it keeps me interested as a writer but also for the audience to be like, “OK, let me think about this more critically.”

It’s important to me to keep that bridge between my non-academic experiences and my academic experiences intact. Because let’s face it, I feel like that’s one of the things that scholars who write about pop culture and music do is tread the line of over academizing something that wasn’t even supposed to be in the academy in the first place. It’s always a concern. But I think the thing that I really loved about Why Bushwick Bill Matters and even Country Soul to an extent, is that there was a nice balance of criticism and narrative.

One of the things I’ve been increasingly thinking about, in part because of the brilliance of your work is, when I think about disability, there’s a particular narrative and framework that comes to mind, and it doesn’t include the South.

In your book, you talk about how to deconstruct the norm. One of the things I’m curious to ask you about in your research in general is how do you see disability showing up in popular music in the region? What space is made to have conversations that probably wouldn’t happen anywhere else?

CH: That’s such a good question. I mean, one of the things that, just to quickly return to the Scarface thing. One of the things that even I, as a huge fan, wasn’t really aware of until I really got into this work is how, I mean, I hate to use the word sophisticated because the implication is of a certain kind of Western and white standard. But there is such a layered and sophisticated way that the Geto Boys talk about mental health. And it is not expected, even among a lot of people who love them. I love that there’s recently been writing by Rodney Carmichael, Kiana-Fitzgerald, and a couple other really great young journalist critic folks who have written specifically about this. Scarface and also Willie D have also talked about using antidepressants. And none of them are doing it in a way that makes it feel shameful or dismissive, which I think is such an important thing and is still too rare but is maybe getting less so.

In terms of pop music, I think, disability has this interesting place. Because it’s not like there has ever been this surplus of perceptively disabled people who have been making pop music. There have been people including the tradition of blind musicians, which is obviously very important in Blues and in other genres.

RNB: Gospel, yeah.

CH: Gospel, yeah. And there’s been some interesting work on that. And there’s actually more that’s happening, including among some artists and activists, too, about that tradition. But then there have also been folks who have had physical conditions that they’ve had to hide or whatever. Then there’s been this post-freak show tradition of putting non-normative looking people or non-normative acting people on stage and leveraging that difference. So you get that tradition. You get that coming out in everything from, certainly from Bushwick Bill, who was really good at negotiating that, I think. But even the way that Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder were marketed in the early days as being these geniuses who were blessed with the other. And then Stevie Wonder calls an album Innervisions just because he knows what he’s doing, too.

In terms of disability in popular culture more generally, in society more generally, it’s often an easy way to promote sympathy and pity, where you’ll have music about people with disability and illness who are presented as tragic or as inspirational. Where you’ll get this thing of, “Oh, if they can make it, so can you.” I love country music. But country music is terrible with this. This is one of the things that country does to pull the heartstrings.

When we’re thinking about things like Horrorcore, there is this monster tradition, which in some ways can be even more liberating. I find it to be much more liberating than inspiration. I think I would much rather have a whole raft of monstrous freaks than sad people who are meant to inspire you through our struggles. I would much rather have that.

Just to circle back a little bit, so much of this does seem to be very much rooted in the parameters of the freak show—parameters which are very closely aligned with minstrelsy. It’s not the same thing, but they intersect. And neither of those is exclusively or even initially a southern phenomenon. But they both are very much connected to ideas of the South and ideas of America. I think we’re still seeing the manifestations of that. Disabled folks have been able to use popular music and popular culture to gain greater acceptance or wealth. But on the other hand, it’s also been tied up with significant coercion and significant exploitation and objectification. And again, in that way, it’s very similar to how the legacy of minstrelsy operates, I think.

RNB: When we think about the South, we can’t get away from the past. It’s one of those things that continuously slaps us in the face. But I am curious about how you feel disability influences the imagination? The southern imagination and what that looks like in terms of establishing these spaces of liberation? With OutKast, Liberation and Freedom was in the act of imagining themselves in different spaces and experiences. Not only its own place, like Stankonia, but they were consistently like, “We’re not even going to stay in these geographically restrictive spaces.”

What would that look, you think, for disabled artists? Or even disabled consumers of pop culture and music. What does that freedom look like? What are the possibilities?

CH: That’s fantastic. That’s such a good question.

RNB: I mean, I try!

CH: I think that one of the things that hip hop more generally has created—and, again, I don’t think this is just a southern thing. But especially because Bushwick Bill and Scarface were such pivotal, early figures, I actually think there is elder quality. There’s a sort of, “They helped originate this.” Unfortunately, now Bushwick Bill is gone. But he has been claimed as an ancestor of the Krip Hop Movement, which is Leroy Moore and Keith Jones’s incredible collective of artists and activists.

Hip hop has created a way to talk outside of respectability for disabled folks, much in the way that it has been for other communities. And I think that the weirdness of southern hip hop is particularly fruitful for this space. Again, this isn’t just a southern thing. Because nobody’s weirder than the Bay. Nobody’s weirder than some of native tongues. I don’t want to rekindle any regional war, please. But the way in which they are able to get outside of those barriers that are not just around the way that we think about southern culture or think about southernness, but also the way we think about respectability more generally. Maybe I’m just looking for the answer I want, but there seems to be a hip-hop ethos in a lot of those contemporary performers, no matter what genre they’re working in. I think it connects to this refusal to be respectable in a traditional way. To push against that, I think that creates a liberatory space. And it’s not within the mainstream really now, or maybe ever will be.

There’s a certain degree to which the disabled musicians—and again, I’m thinking specifically about Krip Hop and the disabled hip-hop movement. There is this network of community and creativity that exists outside of what we would think of as these mainstream or even these traditional spaces. And there’s something there that resonates to me with not only the way that southern hip hop had to come out of Atlanta and other places because nobody was paying attention. But also that assertion, “We are here and the South’s got something to say.” That central thesis, from Andre 3000, continues to resonate. I think that’s where I can see that. And I think that for disabled consumers, for listeners and other folks, I think it taps into those same ideas. That there are these other worlds.

There is this futurist impulse. Because that’s another thing. This is a thing other people have written. I’m hardly the first person to say this. But disabled folks are always put in the past. There’s this notion we get to erase disability in the future, and that’s part of what makes it progress. And it’s very similar with some of the things that Afro Futurists are responding to. There’s this whole assumption that, in the future, with disability, it works out, everything will be “clean” and “fixed.” Therefore we won’t have disability. What disabled artists often do, whatever form they’re working in is, argue for disabled futures. I would love if some folks who are doing really super, futuristic stuff in southern hip hop would think about that. Because they already are, in certain ways.

Missy Elliot or Janelle Monae or whoever making themselves into post-humans. That’s not dissimilar from that. The central thing, and this is an American problem, this is an everybody problem, this is an all kinds of music problem, but I do want disability to be included in the formation of all of these communities. I just want OutKast to come back and do anything, so I’m not going to tell them what they have to do. But if OutKast comes back and they’re creating these new worlds again, I would love for them to talk about, or to at least consider, those experiences. Because they clearly, as you chart so brilliantly in the book, they themselves are a model of growth and thinking.

RNB: Mm-hmm. And I think that’s the next move. One of the questions I always get is, “Oh, what’s in the future of southern hip hop studies? I’m like, “There are so many communities within southern hip hop that we have yet to peel back the layers on.” And I feel like the disabled community is one of them. Queer folks are another one. I think that there is room. And that’s one of the reasons that I’m so very adamant about how complex southern hip hop culture is because these communities exist.

But because we’re still so focused on those touchstones that we associate with “mainstream hip hop.” Like, “Oh, we can recognize that because it’s urban,” “We can recognize it because it’s heterosexual,” “We can recognize it because it’s misogynistic,” or whatever. But there’s also this pushback that exists, and I’m hoping that that continues with the increasing of critical conversations that we’re having.

With this special issue that you are guest editing, what are some of the things that you hope folks will consider or contribute to the issue in regards to pop music in the South?

CH: I mean, you know me. If every submission’s about pop music, I’ll be happy. No, I mean, I would love to see submissions about pop music because it is still a growing thing.

I’m not the first person to do this. But there aren’t actually that many people who are thinking about things in this way. So I would just be thrilled to see anything. And I would particularly be interested to see folks talking about disabled artists. We’re centering disability within the discussion of artists. Whether those artists are super famous or not is not that important to me. I mean, we’re still doing the work of saying we have to remember that this person was disabled. I think about that within the analysis of what we do.

The other thing would be about disability and music within listeners or communities. How are we hearing and experiencing musical culture in the South in a disability context? I think there’s a lot of interesting work to be done about that—that relates to the experience of disability and relates to our understanding of disability. That would be great, too. Or, I mean, honestly, if somebody submitted something about disability in the South on Forrest Gump, that’d be amazing, really. There’s still so much work to be done.

So much to do. But yeah, all the things. I want all the things.

RNB: I love it! We want all of the things. I am so excited about this issue. And thank you so much for your time and letting us talk with you.

CH: And yeah. Thank you.

Regina N. Bradley is an alumna Nasir Jones HipHop Fellow (Hutchins Center, Harvard University, Spring 2016), Associate Professor of English and African Diaspora Studies at Kennesaw State University, a faculty editor for Southern Cultures, and co-host of the critically acclaimed southern hip hop podcast Bottom of the Map with music journalist Christina Lee. She is also the author of Chronicling Stankonia: the Rise of the Hip-Hop South and editor of An OutKast Reader, a collection of essays about OutKast.

Charles L. Hughes is director of the Lynne and Henry Turley Memphis Center at Rhodes College. His acclaimed first book, Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South, was named one of the Best Music Books of 2015 by Rolling Stone and No Depression, one of PasteMagazine’s Best Nonfiction Books of the Year, and one of Slate’s “Overlooked Books” of 2015. His most recent book is Why Bushwick Bill Matters (University of Texas Press, 2021).