Breaking through the discord, there was a harmony: hundreds of tables and chairs scratching against the floor. Trays of corn bread sliding across the tables, uneaten. It was not just the sound, but the smell, too. Spoiled meat and heaps of scraps sunk into the walls amid the summer’s heat. On any day, the carefully choreographed movement of hundreds of women leaving the Wetumpka State Penitentiary dining hall was loud. On July 19, 1934, it was also mutinous.1

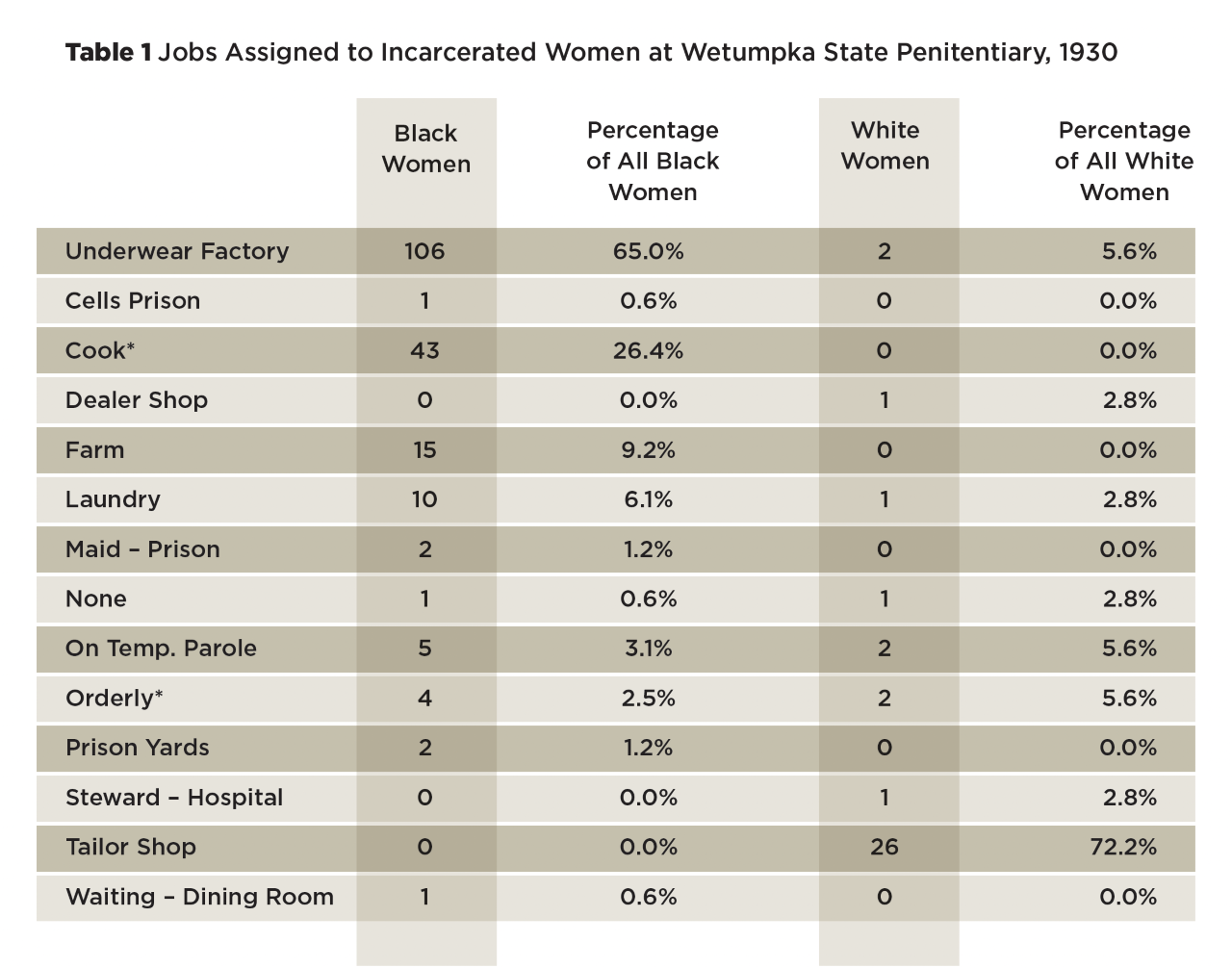

Even though both Black and white women were incarcerated in the Alabama state penitentiary, only Black women worked in the prison kitchens. Guards woke them up as early as two o’clock in the morning to prepare food for the entire prison. Perhaps they were the first to smell the cracklins, left over from the slaughter of fifteen hogs three days earlier. Maybe they whispered throughout the morning service: “The meat [is] spoiled.” After breakfast, as women filed into their segregated prison jobs—Black women to the garment factory and white women to the tailor shop—they passed the word around “not to eat the corn bread.” One hundred and sixty women organized among themselves up until the dinner bell. Once in the dining hall, they staged a walkout.2

Just a week earlier, approximately a hundred miles northeast of Wetumpka, in Gadsden, Alabama, over twenty thousand workers had walked out after management fired five United Textile Workers (UTW) organizers. Two days later, and just five days before incarcerated women staged a walkout at Wetumpka, nearly all forty-two millhand locals in Alabama voted to join the striking Dwight Mills workers. Just as the Alabama cotton mill strikes were galvanizing nationwide protests of industrial cotton mills, rural Black Alabamians were leading a cotton pickers’ strike under the auspices of the Share Croppers’ Union in nearby counties. Across the state, nearly eighty-five thousand workers, from the steam laundry plants in Birmingham to the docks in Mobile, went on strike that year. In response to these large-scale organizing efforts, police, private landowners, and company management attempted to violently suppress organizers across the state, from the plantations to the mills.3

It is within this context of labor organizing in rural and industrial Alabama that the “incipient rebellion,” as state investigators called it, at Wetumpka State Penitentiary comes into stark relief. Histories of labor organizing have delineated how state and private companies wielded carceral power as a repressive end. Many of these narratives of early twentieth-century organizing stop at the threshold of the county jail or the penitentiary. But what happens when we look beyond this precipice? Rather than being merely a coda to labor struggles, prisons were catalysts—sites where people clarified and built labor militancy. In this way, the 160 Black and white women who organized from inside Wetumpka were part of, even if divergent from, the nascent labor movement that coursed through Alabama.4

As Robin D. G. Kelley first argued with regard to Black sharecroppers, early twentieth-century Black workers in rural and urban Alabama alike nurtured resistance in places that the state excluded from labor protections. Gendered and raced notions of whose work counted affected the state’s formulations. Indeed, white power brokers construed these work sites as marginal in large part because of Black women’s presence there. Whether in a white nursery, on a small plot of arid land, or at a sewing machine in the prison factory, Black women’s labor, although essential, was cast as deviant and, thus, disposable. In response to such long-standing exclusions, Black women in the free world and in prison organized against the state’s divestment from them. Like Black laundresses collectively organizing for better wages in nineteenth-century Georgia, incarcerated Black women in Alabama did not seek recognition from the state so much as they envisioned a more radical freedom in spite of it.5

Black women’s labor organizing from within prison produced a movement where there was never meant to be one. On chain gangs, in convict leasing camps, and in the penitentiary, Black women resisted by running away, burning or refusing to wear prison clothes, caring for one another in the night, feigning illness, malingering, and debilitating farm animals. While stories of incarcerated southern Black women’s dissent have been told by Mary Ellen Curtin, Talitha LeFlouria, and Sarah Haley, these modalities take on different significance and a new taxonomy in the context of New Deal–era labor. Indeed, resistance from within the prison was a critical site of Black labor organizing that emerged in spite of the state, rather than in concert with federal protections. In this way, the rippling history of labor struggles at Wetumpka requires us to consider how southern Black women’s absence from early twentieth-century industrial labor organizing might falter if we take a closer look at prisons and their contracts with private companies.6

While the dining hall strike was short-lived, it laid bare the radical potential of burgeoning organizing in the prison. At Wetumpka, there were always far fewer white women: in 1934, for example, there were between two and three hundred Black women incarcerated and only twelve to fifteen white women. However, the southern prison was a new ecology wherein technologies of violence that survived the abolition of slavery and were predominantly used to hurt, maim, and kill Black women could be used against white women. And because white and Black women were incarcerated together at Wetumpka, there was always a mélange of interracial antagonism and cooperation. When cooperation existed, it was often fleeting—disrupted by white women’s assertions of racial domination and attempts to invoke the power to punish Black women even if they themselves did not have the authority to do so in prison.7

The tenuous relationships between Black and white women were deeply personal. At Wetumpka, every aspect of life was intertwined: sex, food, garment machines, beds, rules of conduct, and punishment. Incarcerated women not only worked together, but lived together, even if in segregated cell blocks. Moreover, the prison’s social order was fundamentally organized around white supremacy and depended upon white women, even those incarcerated, to uphold racial boundaries. Often, they towed this line willingly. But on the occasion when Black and white women socialized together or even had intimate relationships with one another, they exploited the prison’s fault lines. For as much as the prison brutally enforced racial domination, it also created opportunity for a unique interracial proximity that could produce intimacy and solidarity.8

For this and other reasons, the story of labor organizing at Wetumpka was necessarily different than at the cotton mills. Incarcerated people captured these differences in their ubiquitous use of the term “free world,” which evoked the experience of being physically close to life outside of prison but decidedly separate from it. One such difference was the effect of New Deal–era labor legislation such as the newly passed National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which expanded opportunities for unionization and established regulatory standards. Within the prison, however, the legislation had no bearing on incarcerated women’s working conditions; there were no hopes for unionization or board-reviewed grievances, no matter how inconsistent those processes were.9

Outside of prison, Black women were largely absent from the cascading cotton mill strikes in the summer of 1934. Long excluded from industrial labor, sometimes directly because of white women’s hostility toward them, southern Black women were consigned to domestic and farm work. Even though factory work in the free world was grueling and punitive, the fact remained that some southern white women chose it as a path toward economic independence. Women incarcerated at Wetumpka—the majority of whom were Black—had no choice. Prison administrators, like the director of the Board of Administration, William F. Feagin, who believed in “utilizing convict labor to the greatest possible extent,” forced Black women to work in the very jobs that they were turned away from in the free world. Unlike Black garment workers in 1930s Harlem who began to fill positions vacated by white women and who joined the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, incarcerated Black women in Alabama were neither paid for their work nor able to unionize.10

Histories of Black women’s labor resistance during slavery and in its aftermath impel us to look beyond prison administrators’ clawing efforts to dismiss claims of systemic unrest. If state investigators assuaged officials’ concerns about the July 19 strike, their swift surveillance and punishment of those involved had, in historian Tera Hunter’s words, “unintended consequences”: it left evidence of the riot’s destabilizing effect. In the aftermath of the strike, some officials even remarked on the growing unrest in the weeks leading up to July 19. Indeed, what the warden called persistent “trouble” offers an important window into late-night conversations and early-morning solidarities that may have existed among the women who had been refusing to get dressed to go to work at the sound of the first bell.11

The warden’s invocation of trouble also may have gestured toward the failure of the prison as a political and social enclosure. Indeed, even though prison administrators, wardens, and guards succeeded at caging people, prison walls were never fully impenetrable. Incarcerated women tested their “porosity” through letters, visits, newspapers, magazines, work assignments outside the prison walls, and sometimes escape. Literally or figuratively transgressing the prison walls was part of Black women’s attempts to devise mutinous and disobedient strategies to survive the violences of incarceration. They rarely resulted in long lengths of freedom. Yet they existed. These strategies made up a disparate collective that stretched from the reopening of Wetumpka State Penitentiary in the early 1920s until its closure two decades later. In wardens’ punishment ledgers and state officials’ correspondence, moments of individual and collective insurrection exist but are subsumed under the state’s imperative to erase any trace of cooperative resistance. They are in plain view but simultaneously well hidden: a through-line that connects the many places where Black women worked and that the state excluded from federal labor protection.12

These shadowed recollections of incarcerated women’s dissent illuminate a bridge between known and lesser-known spaces of labor organizing. By looking beyond the singular moment of the walkout, we might find antecedents and companions to labor organizing in the unassuming, quotidian garb of desire and refusal. Finding spaces of leisure was also a matter of stealing back time from surveillance and penal work. In other words, desiring free time, stealing clocks and fabric from the factory, demanding better food, and seeking companionship were bound up with refusing extractive labor. Weaving the events of July 19, 1934, into the broader context of incarcerated Black women’s participation in sabotage, theft, escape, and queer relationships clarifies how labor struggles coevolved with these quotidian actions. The collation of these moments offers a necessary story of how Black women participated in and led labor struggles from within prison. We must ask how their “incipient rebellion[s]” took root in, or even tilled, the soil of southern radicalism. In so doing, we will find bold moments of oppositional labor politics in a place where workers’ rights did not exist and unions could never reach. Here, labor was a condemnation.

In 1933, state prison administrators worried what the next year would bring. At the time, profits were high—so much so that the Board of Administration, which oversaw state penal camps and prisons, reported revenue from all prison industries. In other words, the prison system not only cost taxpayers nothing but was producing profit. And yet, the Hawes-Cooper Act, passed in 1929 and set to become effective in 1934, threatened the revenue generated by women incarcerated at Wetumpka in Elmore County and other penal industries scattered throughout southern Alabama. The legislation, which banned the interstate sale of prison-made goods in states with laws against it, meant that the garments produced at Wetumpka could no longer be sold by the Lite Wear Manufacturing Company that contracted with the prison. For a time, officials and contractors resisted the incursion on their profits. Indeed, the Supreme Court case that would eventually confirm the law’s constitutionality by 1936 originated from the illegal sale of Wetumpka-made shirts in Ohio. Even after the court’s decision, however, state officials continued to run the factories to some extent, producing clothing for the nearly five thousand people incarcerated across the state.13

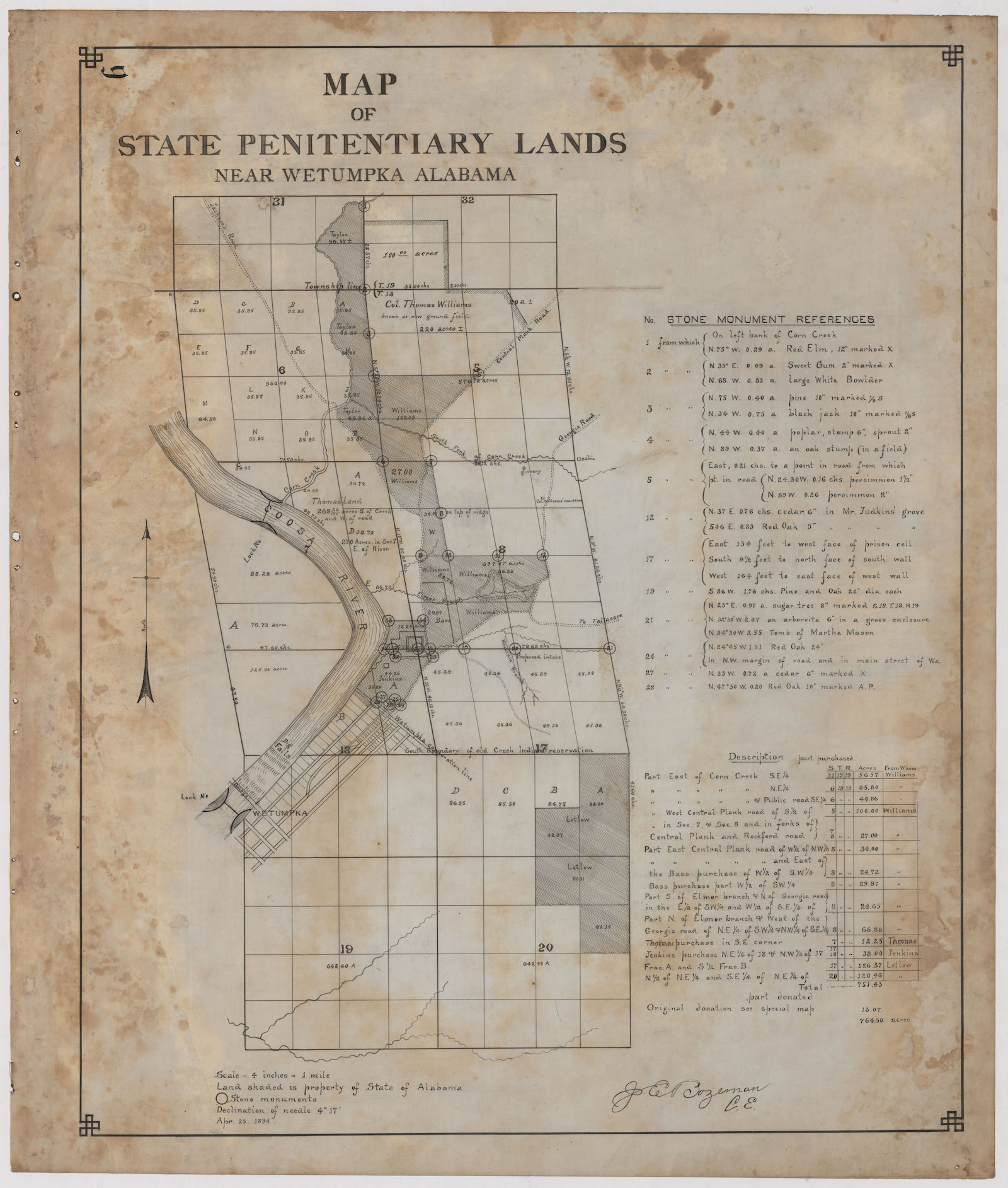

Following the state ban on convict leasing, which took full effect by the end of the 1920s, Alabama’s Board of Administration reconfigured and centralized penal labor. Under the purview of the state, incarcerated people in Alabama labored at mills, in factories, in coal mines, on state farms, on highways, in laundries, in the prison’s tuberculosis hospital, and in guards’ and wardens’ private homes. While Black women were forced to do farm and domestic work during their incarcerations, they were also increasingly assigned to the factory at Wetumpka (see Table 1).14

Because of the various modes of profitable labor and private contracts that circumvented the ban on convict leasing, the Board of Administration urgently organized in opposition to the Hawes-Cooper Act. In the early 1930s, officials drafted a questionnaire that they circulated to other state prison administrators in hopes of galvanizing resistance to the federal policy. Other state officials similarly described their alarm at the loss of revenue. South Carolina’s superintendent, for example, reported that the enactment of the law would be “a very serious blow,” shutting down their manufacturing enterprises. West Virginia’s penitentiary warden summed up his concerns in two words: “very disastrous.” Like Alabama, South Carolina and West Virginia—among other southern states like Virginia and Tennessee—forced incarcerated Black women to work as machine operators, inspectors, cutters, loopers, sewers, and general manufacturers in prison factories.15

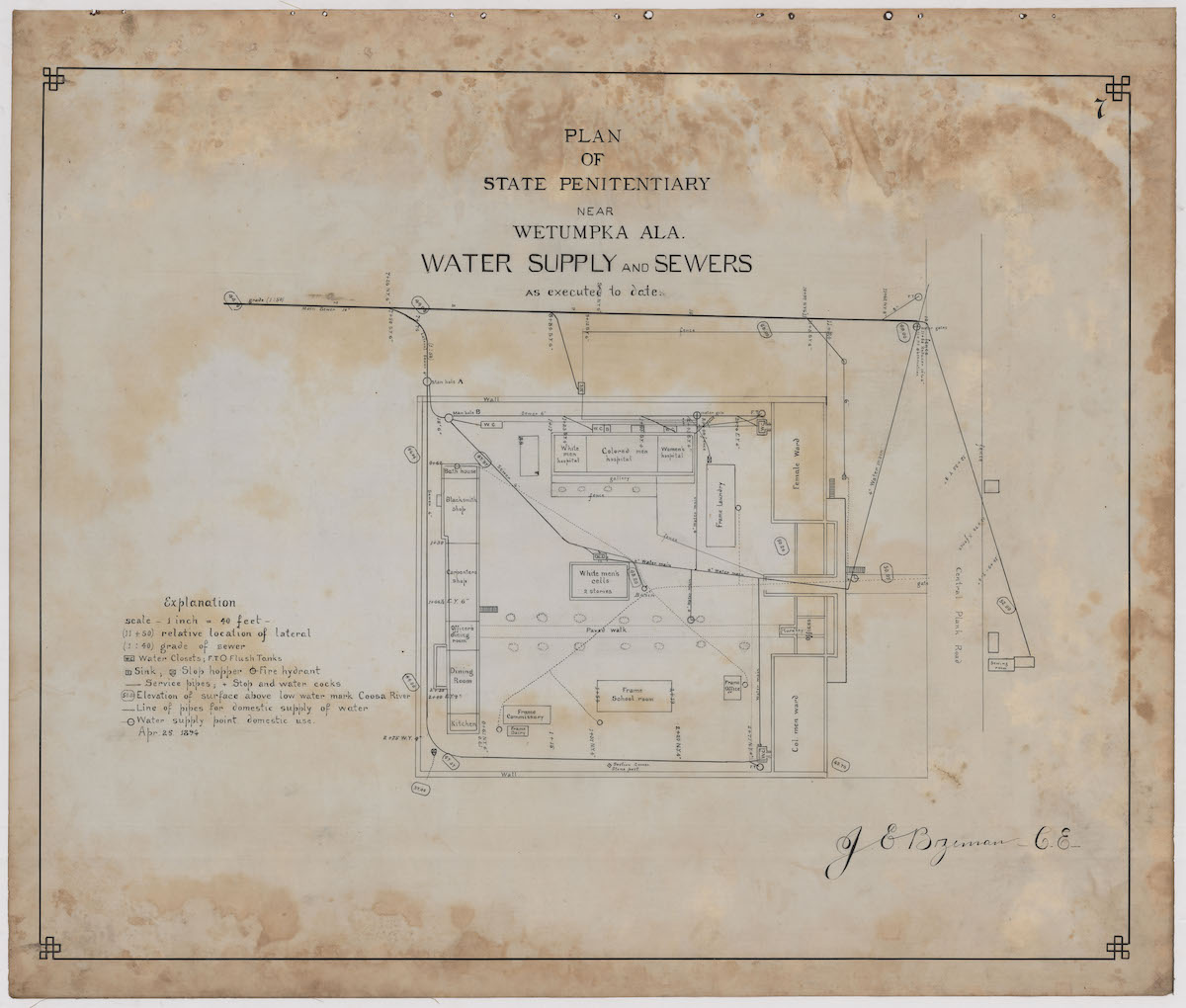

In Alabama, the factory had been a central component of modern carceral infrastructure for at least a decade. In 1922, when Wetumpka State Penitentiary reopened as a place of reformed punishment for women, Frank Willis Barnett, a local journalist, remarked on the so-called improvements, fondly recalling the decaying prison before the “old cells [were] torn out to convert that part of the prison into a factory.” White visitors fawned over the three acres of land enclosed in twenty-five-foot walls; notably, the forced industriousness of incarcerated women enticed observers as much as the “new pickets and lattice fences, all painted snow white.” This Frankenstein marriage of bucolic and industrial fantasies coalesced into a brutal site of discipline and punishment. Factory work was grueling: it included repetitive, arthritis-inducing tasks; long hours; and the ever-present threat of the whip or solitary confinement for failing to produce a specific number of garments. Women filed into the factory at six o’clock in the morning and worked twelve hours except for an hour break at noon; some were on an all-night shift.16

Although the newly reopened Wetumpka incarcerated both Black and white women—and by the 1930s men as well—more Black women were sent to the penitentiary (see Table 2). And unlike in any other state prison or penal camp, Black women outnumbered white and Black men, in large part because Wetumpka was the central prison where women were sent whereas only disabled and aged men were transferred there. Black women’s labor assignments, much like their cells, upheld racial segregation. Most Black women worked in the factory, while most white women were assigned to smaller-scale work in the tailor shop. But the fact that both white and Black women worked in fear of the whip and the guards’ barks meant that they lived in a strange new world.17

These joint (albeit divergent) experiences of discipline and punishment occasionally branched into moments of interracial cooperation. In December 1923, for example, thirty-six women—twenty-five Black and three white (and eight whose names are now unreadable)—wrote to Governor William Brandon demanding that they be allowed to stay at Wetumpka rather than be transferred back to Speigner, another prison where they had faced relentless attacks from guards: “When we were in the cotton mill at Speigner there was some one cut near to death almost every day—both white and colored.” Wetumpka was not a perfect refuge from guards’ ire, but given a choice, the women vehemently opposed being sent back to the cotton mill. The letter suggested that grassroots organizing may have occurred clandestinely during work hours: the youngest Black women to sign it, some of whom were only between the ages of sixteen and nineteen, had never been to Speigner. Perhaps older Black women, like forty-seven-year-old Sarah Barnet, used their decades’ worth of experience in the prison system to convince newcomers to risk punishment and sign their names in support of collective attempts to garner more protection.18

However, cooperation between Black and white women was often fleeting. Incarcerated Black women still understood that white women carried power within the prison, but Black women took opportunities to mock them. In 1929, maybe even well before it, white women complained that Black women began calling them girls, whores, and bitches. These were names that white women prized in their lexicon: daggers they could pull out as condemnations or preludes to violence against Black women whom they perceived as uppity. Girls, bitches, and whores took on a political valence—one that spoke to an alternative sociality in the prison driven by the fact that Black women were far more numerous than white women and did not work for the white women incarcerated alongside them. They could insult incarcerated white women without fear of economic retribution. But it was risky, particularly when a coalition of incarcerated white women reported what was happening to Governor Bibb Graves, calling for retribution and querulously instructing Graves to “respect [his] own race—and see that sompthin [sic] is done.”19

Black women also attempted to reclaim their time from industrial sewing lines in the factory. In October 1928, for example, Bertha Lee Golden refused to work; the next day, Baby Doll Hearn did “bad work,” maybe failing to finish her quota or haphazardly stitching underwear together on purpose. In the middle of the month, Bertha Lee Golden was defiant again: if she had to sit there and work, she was going to cut up the garments so that the state could not sell them. In December, Golden came up short on the number of garments she had to make. The same day, Wellie May Gree did the same. At the turn of the new year, Ruth Brown and Mary Bawes failed to reach their quotas. Throughout 1929, 1930, and 1931, Black women refused work, messing up the clothes they were supposed to produce—some even using the factory scissors to cut up the garments. These were small-scale mutinies, hardly impinging on state-generated income. Yet it was no small feat to cut up “state property” or stand up and refuse to sew one more line in front of prison overseers. Black women’s rebelliousness was a constant protest of penal labor conditions—dissent often curtailed by the constant pressure of surveillance and violence. Brutality kept them at the cusp of open, collective rebellion.20

But riots were never far off even if beatings forestalled them. In January 1931, a fire consumed the factory and several other buildings in the prison compound. Fire alarms pounded in people’s ears as guards shouted at them to march out and drove them into groups in the yard. The incarcerated men and women moved further away from the flames as the heat intensified. There was “a great clamor” as people screamed and demanded to exit the enclosure. Nearby, “a group began trying to batter a hole through a brick wall fifteen feet high.”21

As the fire lapped at the walls, people frantically cried for their lives. The “demeanor” among the men and women crowding outside felt “so threatening” to the guards that they “hesitated to go into the yard.” This was a riot against dying at the hands of a factory gone up in flames. There was precedence for garment factory disasters: the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist fire in 1911 killed over a hundred women and girls in Manhattan. But unlike that moment in which collective grieving and reckoning followed disaster, there was no union to mobilize nor dirge to sing. Instead, the fire at Wetumpka was a moment like so many others in prison: a collective wrought in violence and then caustically dispersed. But even so, for minutes or maybe an hour, incarcerated women and men battered the walls with no guards in sight. Sometime after that, Hamp Draper, a career prison bureaucrat, showed up and commanded attention, buying enough time for extra guards from twenty miles away to arrive and reimpose order and discipline. If Black women held out hope that the factory and all its bedeviling coercion was destroyed, they soon learned how quickly the state would rebuild its infrastructure to serve its own ends. If one of the women had set the fire, the relief that they hoped for in its destruction did not last very long.22

By the fall of 1931, less than a year later, Black women were back to working in the garment factory. Through sabotage and truancy, they continued to steal their time away from sewing. In October 1931, Willie Jackson tore up one of the machines. In the spring of 1932, Helen Scott left her work station. The same month, Lenora Hines stole one of the clocks from the factory. Maybe she wanted her own clock, to see if the guards were lying about the time; or perhaps she thought if she could take away the clock, overseers might not be able to count their work to the very minute.23

But even when they did not destroy physical parts of the factory, Black women were irreverent in their penal work. In 1934, for instance, the warden of Wetumpka wrote to the State Board of Administration that Clara Jackson had been causing “considerable trouble … for sometime [sic].” In 1928, she tried to escape with Annie Davis, another Black woman who worked in the prison kitchens alongside her. After being recaptured, she had gotten into fights in the factory and had cursed and threatened guards. Despite her lengthy record of antipathy toward prison officials, a state bureaucrat at some point promoted Jackson to Class A—the state’s highest behavior classification that restored previously withheld rights, like receiving mail, to incarcerated people. Around the same time, the warden made her a “cell tender”: someone who walked the cells at night watching others. But if the administration thought that this position would somehow subdue her, they were wrong. Just three months before the prison-wide strike, Jackson ambled up and down the cells cursing “the warden and doctor in particular.” The night guard yelled at her until she stopped around ten o’clock. But in the morning, she began again, cursing the man who ordered their whippings and the doctor who stood by and watched. When the warden found out, he took away her job, and recorded that he “put [her] in stripes and sent [her] to the field” to work. She screamed. They were violent with her.24

Yet Jackson was determined. After being forced toward one of the roads that cut across state prison lands, she refused to walk further. Her voice testified to a pain so deep that it could not be culled nor extirpated: not by the striped uniform, not by the farmwork, not by fourteen days that they left her with only bread and water in solitary confinement. The warden later noted how she stood out on the highway, “cursing, crying, and yelling.” She screamed at a white woman whose husband was an overseer in the factory and she yelled in front of a bus full of white school children on the road. She did not need their witness but she implicated them in her pain. It was, in historian Marisa Fuentes’s words, “a different form of agency—one that [did] not expect resolution or revolution in outcome,” but was a “will to survive” and a lasting cry of refusal.25

All of these sojourns—and any others that escaped the punishment ledger—culminated in the 1934 strike. It began on a hot summer’s day in 1934. Prison officials from Wetumpka State Penitentiary sent fifteen slaughtered hogs to Montgomery to be put on “cold storage”; the end of July was drawing near and temperatures crested in the nineties. When the warden sent one of the prison guards from Wetumpka to retrieve the meat the next day, the livers were already spoiled.26

On the morning of the strike, one of the night guards, Mr. Edwards, reported that women were dragging their feet and refusing to get dressed at the toll of the first bell. This was not an isolated incident. Apparently, they “[had] been having some trouble getting the [women] up” for some time. When everyone poured into the dining hall for breakfast, Edwards overheard some women “fussing about” his barking demands that they wake up earlier.27

After breakfast, the women filed into their stations to work long hours in the factory that required them to achieve ever-increasing daily tasks. By the time dinner, the noontime meal, rolled around, organizing had occurred en masse during laboring hours. Word spread that some of the meat that they had brought back from Montgomery was spoiled.28

During the walkout, Black and white women defied the organizing principle of modern carceral punishment by “marching out of mess hall in a body before the proper time.” Julia Floyd, a Black woman sentenced just two years earlier for a fifty-year sentence, and Hattie Mae Guthrey, a white woman who only had a ninety-day sentence, led the coalition. Following their lead and possibly organizing others as well were two Black women, Lucinda Allison and Mary Jackson, along with eleven white women. When the bell rang to return to work at one o’clock, however, many of the Black women in the group left the strike, likely fearing being whipped or spending endless days in solitary confinement. Perhaps they did not trust that the white women would not betray them when all was said and done. One of the white leaders tried to continue the strike in the tailor shop, but ultimately returned to work herself. She refused to fully relent, though, and hid in the toilet for most of the afternoon.29

Wardens and guards made a list and punished the women whom they believed had led the strike: men, who may not have eaten at the same time, were conspicuously absent from the day’s events. Afterward, state investigators came into the prison and interrogated participants. One Black and one white leader of the strike—Julia Floyd and Hattie Mae Guthrey—endured solitary confinement for up to two days. The rest were demoted in their behavioral class and forced to wear striped uniforms. Perhaps some of the white women felt more emboldened to challenge carceral authority, because their sentences were shorter and many had only come to prison a month or two earlier. White women also systematically faced less punishment than Black women. Yet Black women, the oldest of whom was fifty-year-old Mary Jackson, too risked their bodily safety to participate in this collective moment of struggle that had to do with so much more than spoiled meat. Even after the bell rang, Jackson and forty-one-year-old Lucinda Allison refused to return to work.30

Despite the brevity of the strike, anger was palpable. When any one woman refused to work, dragged her feet, or tried to reclaim her time from the state, she contributed to the outgrowth of collective dissent. These movements against penal labor were not always as cohesive as the day of the dining-room strike. Sometimes, they were made up of disparate actions. Black women’s collective labor resistance lived in the day-to-day of the factory as much as it did in the moments of crisis. It was when Willie Jackson failed to complete her task, perhaps purposefully, and destroyed her machine. It was when Lenora Hines stole a clock from the factory. It was when Mabel Williams—with stiff fingers and swollen joints—operating two machines to make ninety-six socks a day, told anyone sitting close by that she would fall short of that number every day until they took her off of the night shift. Or when she insisted that she had a right to be asleep in her cell, and not at the machines, when she was sick. It was after the strike ended and Oscie Pearl Toney stole material from the factory. Or when Marie Gunter, who had unsuccessfully tried to run away three months before the strike, sabotaged some of the machinery to slow down the work she was forced to do.31

The insurgence that percolated in late summer 1934 was the product of these experiences in the prison and, perhaps, those carried inside from the free world. Before her incarceration, Julia Floyd, one of the leaders, lived in Macon County, where she likely labored as a sharecropper or tenant farmer. Floyd probably witnessed the growth of first the Croppers’ and Farm Workers’ Union and then the Share Cropper’s Union (SCU), where Black farmers began to organize. Right before she would have entered prison, Floyd’s home county had thirty dedicated union members with an organizational structure that included women’s auxiliaries.32

How did Floyd understand her role organizing a march-out in relation to the labor organizing that began to gain momentum in the Black Belt? Did she think about how members of the scu armed themselves in confrontations with landlords? Did she consider the tactics she likely witnessed, and possibly participated in, when she whispered about collective refusal in the factory earlier that day? In the summer of 1934, the SCU leaders organized a series of cotton pickers’ strikes around the same time of the women’s walkout. Indeed, Elmore County itself was both a SCU stronghold and the home of Wetumpka State Penitentiary. As historian Robin D. G. Kelley suggests, “as tales of the union’s stand … spread from cabin to cabin, so did the union’s popularity.” Perhaps we can expand this: Did stories travel from cabin to cell?33

The SCU was not the only labor organization picking up momentum. Cotton mill workers across the state, beginning in Gadsden, revolted against the “stretch-out,” a newfound strategy that companies used to keep costs low and production high in the aftermath of the passage of an eight-hour workday. Management fired workers and required more production from the ones whom they retained. Perhaps incarcerated women at Wetumpka knew about the massive cotton mill strikes that unfurled just a week before the walkout. News of a galvanized labor movement may have traveled through letters or visitors; connections may have been drawn between the stretch-out and the ever-increasing tasks that they had to finish in the prison factory. Or maybe it was the newspapers that came past the penitentiary walls every so often. Did incarcerated women read the papers and plaster their walls with disobedient words and pictures?34

Some of these things cannot be known, but they emerge from what is known, like several white women’s personal proximity to unionizing industries. Eighteen-year-old Effie McKeever’s father and brother, for example, were respectively a motorman and trapper in the Walker County coal mines. After years of violent repression, the same legislation that opened pathways for cotton mills to unionize spurred local organizing under the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Perhaps McKeever’s family members were among the miners that slipped under fences to escape company deputies and seek refuge in newly unionized mines. Another walkout leader, Glady Williams, likely still had family and friends in a cotton mill town when she went to prison. Williams’s husband, who worked in the electrified cotton mill in Chambers County, may have written Williams letters or managed to make the nearly sixty-mile journey to the prison to discuss the glut of spies, guards, and checkpoints set up by management to search incoming cars and disrupt organizing. We may never know about some of the most intimate and urgent conversations that took place between the prison and free world. Careful deposits of knowledge were purposefully illusive, escaping the state’s records as soon as the words left someone’s lips or notes passed between hands, the prison, and the free world.35

Regardless of how these conversations took place, it would not have been difficult for Black and white women alike to draw connections between the surveillance and repression they (or loved ones) experienced as workers in the free world and what they encountered in prison. Outside of prison, Black women were already vulnerable—as laundresses, sharecropper and tenant farmers, and domestic workers—to constant supervision, punitive deprivation of wages and crops, and violent retribution. Working-class white women who grew up, lived, and sometimes worked in factory towns experienced their own entangled version of surveilled work and life.36

Likewise, incarcerated women knew the differences keenly. If companies like those that ran cotton mill towns falsely promised, according to one local journalist, “their employees good machines, well ventilated places . . . and comfortable homes” to extract more work, prison administrators only offered the illusion of beauty and reform to white visitors. Inside of the prison, there was no private space—walls that had once had pictures cut out from magazines might by the end of the day have prison rules and regulations pasted over them. Bacteria festered in the water. Black women like Carrie Martin were thrown in solitary confinement for two weeks in abject darkness for destroying state property. In the end, violent punishment and deprivation was what “[paid] in dollars and cents.”37

The women who endured these violences day-in and day-out knew that resistance took root, flourished, and withered away in different ways in prison. There are no extant organizational documents that detail labor resistance from within Wetumpka State Penitentiary like we might see in histories of outside unionization; paper trails would have been too risky. Maybe those documents never existed. Moreover, incarcerated communities were transient: people did leave prison. Some were released; others transferred; and still some tried to escape. Others remained, watching all their companions return to the free world over time. In this way, transience posed another kind of obstacle to organizing, because people and relationships were vulnerable to the disruptions of prison time: getting out, being sent back, going to solitary confinement, sometimes not knowing bunk-mates for more than a few weeks at a time. Even if organizational power could build and survive the whip and solitary confinement, it was built on shifting ground.

The interpersonal dimensions of organizing also created challenges. Sex and lost love made factory work deeply personal. Eighteen-year-old Oscie Pearl Toney slept with twenty-one-year old Lucinda Davis for some time before Toney attempted to end things amicably, but Davis was angry and attacked Toney several times. On June 10, 1934—just a month before the walkout—Toney was talking to some other women when Davis took scissors from their stations in the factory and stabbed Toney in the chest, leaving her wounded. Every day thereafter, Toney would have to go to work bearing the trauma of that episode.38

Yet, even though sexual relationships may have complicated and bruised collective organizing, they also served as a form of resistance to carceral labor regimes. Prison rules attempted to deny incarcerated women pleasure and love in the name of work and discipline. Fleeting traces of queer intimacy—mediated by but also acknowledged in state records—were imbricated in women’s struggles against the cruelty of penal labor. The erotic was, in theorist Stephen Dillon’s words, “a way of wanting more than the given state of things”—or of wanting the things that the state withheld.39

Evelyn Lindsay and her lover wanted more than the state would give them. In May 1935, Warden Henry Jones demoted Evelyn Lindsay for sixty days and forced her to wear stripes for “the offense of corporal intimacy with a colored female.” Lindsay, whose incarceration began in October 1934, tried to escape just nine days after she entered Wetumpka State Penitentiary. She was young—eighteen years old—and transient. The unnamed Black woman with whom Lindsay had a sexual relationship may have been Bertha Youngblood, whose punishment three days earlier was dubiously recorded as “removed by order [of] Hamp Draper,” the same man responsible for quelling the riot on the night of the fire.40

Prison officials condemned Lindsey for not just having sex with a woman but a Black woman. Her social subversion of white supremacy was bound up in the unsanctioned ways in which Lindsay and the other woman may have touched each other. In a racial regime that instructed white women to be available for white men only, these moments of interracial intimacy threatened racial, sexual, and gendered order. Perhaps their closeness reminded prison officials of the year before, when Black and white women walked out together, threatening similar orders of the prison. The same carceral structures that segregated labor and created tiers of racialized economic exploitation likewise prohibited interracial sexual intimacy.41

It is worth noting that being in prison confounded the boundaries of consent and coercion. Without the voice of either woman, there is no way to know exactly how they became intimate. There may have been violence, or love. There may have been something in between. Their sexual encounter might have emerged out of desperate moments of loneliness or exciting feelings of transgression. In this exchange of intimate pleasures, Lindsay and this Black woman entered into a relationship that was racially transgressive, potentially socially transformative, and thus punishable.

Every action taken in prison was not the same. In fact, Black and white women’s efforts to carve out space for themselves challenged how the prison collapsed all aspects of their lives together. Sex was not a work stoppage, nor was it a prison-wide riot. But these were related modalities. Seizing upon erotic pleasure was to have a “deep and irreplaceable knowledge,” in Audre Lorde’s words, “of [one’s] capacity for joy.” This reclamation of joy mattered to incarcerated women as both a personal and political gesture. Indeed, these were resistive desires: architectures of joy that inherently ran up against the prison order and its condemnation of them. But there was also the threat of violence: from wardens, overseers, and guards, but also from other incarcerated people. Seizing upon moments of joy, then, was mired in the complexity of relationships wrought in prison. A mixture of pain, pleasure, coercion, and agency defined carceral living and dying; and it equally defined how Black women chose to survive and resist state punishment. If refusing to eat spoiled meat drew a through-line between the dining hall and the factory, finding partnership in the clutches of hell was also a way of dissenting from the terms of penal labor. Both were a recuperation of desire.42

Pleasure and desire, when they did exist in these relationships, was an important key to the story of labor resistance. Pleasure was emblematic of Black women’s attempts to reclaim everything withheld by the state and reject anything enforced by it. In Alabama, prison officials attempted to regulate every minute of Black women’s lives, from their labor to their affections. In order to reclaim, in Cathy Cohen’s words, “small levels of autonomy,” Black women often made choices that the state deemed profane and subversive. They refused to eat; they stole from the factory; and they destroyed machines. And they also built queer relationships, romantic or platonic, that stood outside of normative filial structures. These were choices made, to evoke Cohen once more, “in pursuit of goals important to them … such as pleasure, desire, recognition, and respect.” And the means by which they achieved these goals tied together Black women’s labor resistance and pleasurable pursuits. Both were rooted in the fact that every manifestation of their autonomy was evidence of their deviance.43

In Alabama prisons, there was a vital relationship between economic exploitation, deviance, and queerness. These stories, rooted in the now-hushed ground where the penitentiary once stood, reveal these connections. The state’s records lay bare how the notion of queerness, as many Black feminist and queer theory scholars have argued, was both about sexual desire and nonnormative position within the state. Indeed, state actors often described Black women’s economic and political marginalization as sexual deviance; and their existence as queerly outside of normative womanhood. It was from this vexed positionality that incarcerated Black women built oppositional politics. Piecing together a more capacious southern labor history, then, brings our attention to the 1934 strike as both an essential site of Black labor and queer politics. In this way, it is not just Black women’s presumed absence from southern factories and their labor movements that requires reconsideration. Instead, Black women’s resistant presence—in all of the traces that they left behind—turns our attention to the radical potential of a queer labor politic that knew the importance of pleasure and, in turn, refused the state as an ally.44

This essay first appeared in the Abolitionist South Issue (Fall 2021: vol. 27, no. 3).

Micah Khater is a doctoral candidate in the departments of history and African American studies at Yale University. Her research focuses on race, gender, incarceration, disability, and memory. You can find more of her work, creative and academic, at micahgracekhater.com.NOTES

Immense gratitude for the generative and multidimensional feedback that I received on this article from Micah Jones, Teona Williams, Garrett Felber, Emma Calabrese, and the peer reviewers. I am also thankful for Crystal Feimster’s support and incisive questions about the petitions written by incarcerated women. This work was funded by the Center for Engaged Scholarship; the Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration; and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition.

- “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, July 19, 1934,” box SG17647, folder “Correspondence with Warden 1934,” Alabama Department of Corrections and Institutions Administrative Correspondence, 1909–1947, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama (hereafter cited as Administrative Correspondence).

- “Letter from L. D. Carlton to Hamp Draper, January 25, 1928,” box SG17646, folder “Escapes and Recaptures, 1923–1931,” Administrative Correspondence; “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, July 19, 1934”; “Letter from George P. Walls, Paul King, and [?] to W. M. Feagin, July 20, 1934,” box SG17647, folder “Correspondence with Warden 1934,” Administrative Correspondence. For segregation of prison labor assignments, see “Report of Prison Labor Assignment, Creditable to Operations at this Prison for November 1931,” box SG17646, folder “Correspondence with Warden, 1931,” Administrative Correspondence.

- Janet Irons, Testing the New Deal: The General Textile Strike of 1934 in the American South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000); Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Robert Korstad, and James Leloudis, “Cotton Mill People: Work, Community, and Protest in the Textile South, 1880–1940,” American Historical Review91, no. 2 (April 1986): 245–286; Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 54–55, 69–70.

- “Letter from George P. Walls”; Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “Disorderly Women: Gender and Labor Militancy in the Appalachian South,” Journal of American History 73, no. 2 (September 1986): 366. For literature on prison organizing traditions, see Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (London: Verso, 1996); Heather Ann Thompson, “Rethinking Working-Class Struggle through the Lens of the Carceral State: Toward a Labor History of Inmates and Guards,” Labor: Studies in the Working Class History of the Americas 8, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 15–45; Dan Berger, Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (New York: Vintage Books, 2016); Robert T. Chase, We Are Not Slaves: State Violence, Coerced Labor, and Prisoners’ Rights in Postwar America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, “Organized Inside and Out: The Angola Special Civics Project and the Crisis of Mass Incarceration,” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 15, no. 3 (2013): 199–217; Mike Elk, “The Next Step for Organized Labor? People in Prison,” Nation, July 11, 2016, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/the-next-step-for-organized-labor-people-in-prison/ ; Kim Kelly, “How the Ongoing Prison Strike Is Connected to the Labor Movement,” TeenVogue, September 4, 2018, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/labor-day-2018-how-the-ongoing-prison-strike-is-connected-to-the-labor-movement ; and Dan Berger and Toussaint Losier, Rethinking the American Prison Movement (New York: Routledge, 2018). Much of the field has focused predominately, if not exclusively, on incarcerated men. For a notable exception, see Emily L. Thuma, All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing, and the Feminist Fight to End Violence (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2019). Mary Ellen Curtin writes about nineteenth-century Alabamian incarcerated male coal miners as imbricated in and central to labor organizing during and after their incarcerations. Mary Ellen Curtin, Black Prisoners and Their World, Alabama, 1865–1900 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000).

- Kelley, Hammer and Hoe; Tera W. Hunter, “Domination and Resistance: The Politics of Wage Household Labor in New South Atlanta,” Labor History 34, no. 2/3 (1993): 205–220; Tera W. Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997); Julie Saville, The Work of Reconstruction: From Slave to Wage Laborer in South Carolina, 1860–1870 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Jacqueline Jones, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present (New York: Basic Books, 2010).

- Curtin, Black Prisoners and Their World; Talitha L. LeFlouria, Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015); Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016); Kali N. Gross and Cheryl D. Hicks, “Introduction to Gendering the Carceral State,” The Journal of African American History 100, no. 3 (2015). For prison factory development and Black women in the American West, see Anne M. Butler, Gendered Justice in the American West: Women Prisoners in Men’s Penitentiaries (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997).

- AFC 1935/002, AFS 00225 A02, Disc Jacket “B” from John Lomax’s Recordings at Wetumpka Penitentiary, 1934, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. In 1930, for example, three white women were whipped for fighting and trying to “break into the men’s department.” Box SG016427, pp. 41, 47, Records of Punishment, 1928–1951, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama (hereafter cited as Records of Punishment). See also Sarah Haley, “‘Like I Was a Man’: Chain Gangs, Gender, and the Domestic Carceral Sphere in Jim Crow Georgia,” Signs 39, no. 1 (Autumn 2013): 53–77.

- Robin D. G. Kelley, “‘We Are Not What We Seem’: Rethinking Black Working-Class Opposition in the Jim Crow South,” Journal of American History 80, no. 1 (June 1993): 78.

- “Letter from Mary Osborn to Governor W. W. Brandon, July 12, 1923,” box SG17570, folder “O 1920–1924,” Administrative Correspondence; “Letter from J. H. Bonner to Mr. H. C. Flowers, May 27, 1943,” box SCG17650, folder “Escapes and Recaptures, 1943–1947,” Administrative Correspondence; Irons, Testing the New Deal.

- Hall, “Disorderly Women,” 381; “Feagin Report Shows Profit on Convict Operations in 1933–1934,” Wetumpka Herald, December 13, 1934. Unless otherwise noted, all newspaper articles cited in this essay were digitized and downloaded from Newspapers.com. For southern Black women’s exclusion from industrial work, see Hall, Korstad, and Leloudis, “Cotton Mill People”; Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom, 120; and LeFlouria, Chained in Silence, 62–63. On Black garment workers and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, see Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), esp. p. 48; Janette Gayle, “Sewing Change: Black Dressmakers and Garment Workers and the Struggle for Rights in Early Twentieth Century New York City” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2015); and Julia J. Oestreich, “They Saw Themselves as Workers: Interracial Unionism in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and the Development of Black Labor Organizations, 1933–1940” (PhD diss., Temple University, 2011).

- Hunter, “Domination and Resistance,” 214; “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, July 19, 1934.” In the carceral context, see LeFlouria, Chained in Silence; and Haley, No Mercy Here.

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), esp. 263–286. The analysis of the porosity of prison walls is informed by the wisdom of my friend, eae benioff. I attend to what existed at the precipice of violence in line with Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

- Archival Description, Correspondence Concerning the Hawes-Cooper Act, 1926–1933, box SG008557, Administrative Correspondence; “Feagin Report Shows Profit”; “Benton Appointed to State Position,” Montgomery Advertiser, February 21, 1923; “The Hawes-Cooper Act and Alabama Convict Goods,” Birmingham News, March 5, 1936; “State Little Affected by Rule on Prison Goods,” Evergreen Courant, January 7, 1937. Alabama also had the “most profitable prisons in the nation” in the nineteenth century. Curtin, Black Prisoners and Their World, 2. The continuation of factory work is corroborated by box SG016429, p. 66, Records of Punishment.

- “History of the ADOC,” Alabama Department of Corrections, accessed May 20, 2021, http://www.doc.state.al.us/history#:~:text=When%20the%20territory%20of%20Alabama,not%20want%20a%20prison%20system ; Fifteenth Census of the United States, Wetumpka State Penitentiary, Population Schedule, Precinct 8 Wetumpka, Elmore County, Alabama, 1930. All censuses cited in this essay were digitized and downloaded by Ancestry.com.

- Box SG008557, folder “Essential 1932–1933 (Questionnaires and Answers Concerning H. C. Federal Act),” Administrative Correspondence; State Penitentiary, City of Columbia, Richmond County, South Carolina, Fifteen Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Sheet 1A–6B; West Virginia Penitentiary, Moundsville City, Marshall County, West Virginia, Fifteen Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Sheet 1A–23B; Virginia State Penitentiary, Richmond City, Henrico County, Virginia Fifteen Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Sheet 1A–8B; State Penitentiary, 8th District Township, Davidson County, Tennessee, Fifteen Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Sheet 1A–20A.

- “Prison for Women at Wetumpka Is Apparently Justifying Itself,” Birmingham News, January 21, 1923; “State Penitentiary Prepares for Women,”Montgomery Advertiser, November 9, 1922; “Letter from J. F. Sewell, Physician Inspector to G. M. Taylor, Physician Inspector and Surgeon, October 6, 1933,” box SG17647, Administrative Correspondence.

- “Report of Prison Labor Assignment.” Reports of prison demographics, for instance, suggested that in October 1933, there were 143 Black women and sixty white women. This challenged officials’ earlier supposition that white women’s numbers in the prison would not increase far beyond the numbers in the early 1920s, which were somewhere around ten white women. “Letter from J. A. Howle to Roy L. Nolen, January 26, 1924,” box SG17646, folder “Correspondence with Warden 1924,” Administrative Correspondence; and “Letter from J. F. Sewell to G. M. Taylor, October 13, 1933,” box SG17649, folder “Correspondence with Physician, 1931–1934,” Administrative Correspondence.

- “Letter from the Entire Women Department at Wetumpka Prison Walls to Governor William W. Brandon, December 20, 1923,” box SG17646, folder “Correspondence with Warden 1923,” Administrative Correspondence; “Letter from the Entire Women Department.” Information regarding age, incarceration dates, and race were determined by cross-referencing names on the petition with information collected at intake and recorded in the Alabama Convict Records digitized by Ancestry.com.

- Box SG16427, pp. 3, 5, 20, 43, Records of Punishment; “Letter from ‘Inmates of Wetumpka Prison’ to Governor Bibb Graves, July 16, 1929,” box SG17646, folder, “Correspondence with Warden 1929,” Administrative Correspondence.

- Box SG016427, pp. 1, 6, 16, 19, 40, 42, 60, Records of Punishment. See Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom, for an earlier history of Black women’s reclamation of free time after Emancipation.

- “Jokes Keep 562 Convicts from Panic as 92-Year-Old Alabama Prison Burns,” New York Times, January 25, 1931, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Jokes Keep 562 Convicts from Panic.”

- Box SG016427, pp. 60, 77, 80, Records of Punishment.

- “Statement of Sentence: Clara Jackson, April 4, 1934,” box SG17653, folder “J,” Administrative Correspondence; “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, April 3, 1934,” box SG17653, folder “J,” Administrative Correspondence. It was a well-established practice to have doctors present and justify punishments. See, for example, “Letter from F. E. Prickett to William F. Feagin, June 21, 1922,” box SG17578, folder “Y 1920–1926,” Administrative Correspondence. I discuss the presence of doctors during torture in prison elsewhere in my dissertation: Micah Khater, “‘Unable to Find Any Trace of Her’: Black Women, Genealogies of Escape, and Alabama Prisons, 1920–1950.”

- Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives, 143. “She screamed at a white woman whose husband was an overseer in the factory” refers to Herman C. McKemie and his spouse, Ida B. McKemie. See “Herman C. McKemie,” Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Wetumpka Precinct 8, Elmore County, Alabama. For newspaper articles that reference the racial makeup of busing in the early 1930s in Elmore County, see “School Bus Drivers,” Wetumpka Herald, September 6, 1934; “School Bus Routes to Be Let, Notice,” Wetumpka Herald, June 19, 1930; “Minutes of the Meeting of the Elmore County Board of Education Held Friday, September 22, 1933,” Wetumpka Herald, November 16, 1933; and “Minutes of County Board of Education,” Wetumpka Herald, November 12, 1931.

- “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, July 19, 1934”; “The Weather,” Montgomery Advertiser, July 18, 1934.

- “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, July 19, 1934.”

- “Daily Task for Manufacturing Underwear at Wetumpka Prison, May 7, 1931,” box SG17646, folder “Correspondence with Warden, 1931,” Administrative Correspondence.

- “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, July 19, 1934”; “Letter from George P. Walls”; “Letter from J. E. Brock to Wm. F. Feagin, July 19, 1934,” box SG17550, folder “Aa–Ar, 1933–1935,” Administrative Correspondence.

- “Letter from George P. Walls”; Box SG016427, p. 52, Records of Punishment; “Letter from J. E. Brock to Wm. F. Feagin, July 19, 1934,” box SG17550, folder “Aa–Ar, 1933–1935”; “Entry for Lucinda Allison,” Alabama Convict Records, vol. 17: 1933–1934, pp. 356, 642. There is no mention of any men during the events of July 19, 1934. In 1930, many did work in the factory, but by 1934, it is less clear whether this was still the case; see Fifteenth Census of the United States, Population Schedule, Precinct 8 Wetumpka, Elmore County, Alabama, 1930; and collated data derived from Records of Punishment, box SG016427. For information regarding the leadership of the strike, see Alabama Convict Records. See collated data derived from box SG016428, Records of Punishment. For information regarding the leadership of the strike, see Alabama Convict Records.

- “Letter from G. M. Taylor and J. D. Reese to Wm. F. Feagin, January 23, 1934”; “Letter from J. E. Brock to Wm. F. Feagin, December 22, 1933,” box SG017576, folder “Wi 1934,” Administrative Correspondence. Collated data derived from box SG016427-8, Records of Punishment. For more information on Marie Gunter, see “Entry for Marie Gunter,” Alabama Convict Records, vol. 16: 1932–1933, p. 620; and “Letter from J. E. Brock to William F. Feagin, March 18, 1934,” box SG17647, folder “Escapes and Recaptures, 1932–1934,” Administrative Correspondence.

- Kelley, Hammer and Hoe, 44–55. See also, “Entry for Julia Floyd,” Alabama Convict Records, vol. 16: 1932–1933, p. 462.

- Kelley, Hammer and Hoe, 48–49, 55.

- Irons, Testing the New Deal; Hall, Korstad, and Leloudis, “Cotton Mill People”; “Prison for Women at Wetumpka.”

- “Letter from George P. Walls.” See also, Alabama Convict Records and Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Nauvoo, Alabama; Fairfax, Alabama; Florence, Alabama; and Limestone County. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Precinct 34, Walker County, Alabama; Iris Singleton McAvoy, Images of America: Walker County Coal Mines (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2016), 8; Irons, Testing the New Deal, 124. For women’s attempts to smuggle out mail, see box SG016427–8, Records of Punishment.

- Hall, “Disorderly Women,” 364.

- “Letter from J. A. Howle to Roy L. Nolen”; “Alabama State Board of Health, State Laboratory and Pasteur Institute, Montgomery, Alabama, September 23 and 28, 1925 Inspection,” box SG17646, folder “Correspondence Re: Water Supply, 1925–1932,” Administrative Correspondence; Records of Punishment, box SG016428, p. 22, Administrative Correspondence; “Prison for Women at Wetumpka.”

- “Entry for Oscie Pearl Toney” and “Entry for Lucinda Davis,” Alabama Convict Records, vol. 17: 1933–1934, p. 517 and vol. 16: 1932–1933, p. 2; “State of Alabama Convict Department, Preliminary Report of Accident, Wetumpka, June 10, 1934,” box SG17647, folder “Accident Reports, 1931–1934,” Administrative Correspondence.

- Stephen Dillon, Fugitive Life: The Queer Politics of the Prison State (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 142. For interracial and queer relationships in carceral settings in the North, see Cheryl D. Hicks, Talk with You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890–1935 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

- “Letter from Henry Jones to Hamp Draper, May 28, 1935,” box SG17566, folder “La-Ll 1935,” Administrative Correspondence; “Entry for Evelyn Lindsay,” Alabama Convict Records, vol. 17: 1933–1934, p. 920; “Entry for Bertha Youngblood,” Alabama Convict Records, vol. 17: 1933–1934, p. 127. While all Lindsay’s information matches the letter dated May 28, 1935, including the state-issued number during her incarceration, she is listed as being from Jefferson County in one place and Mobile in another. This may have been a discrepancy, as was sometimes the misspelling of names, but it may have also indicated confused nativity. She may have been arrested in Mobile, as her intake suggests in the convict record, but been from Jefferson.

- Regina Kunzel has written extensively about the confused discourse surrounding interracial sexual relationships; see Regina Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008). Estelle B. Freedman, “The Prison Lesbian: Race, Class, and the Construction of the Aggressive Female Homosexual, 1915–1965,” Feminist Studies 22, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 397–423. See also, Cookie Woolner, “‘Woman Slain in Queer Love Brawl’: African American Women, Same-Sex Desire, and Violence in the Urban North, 1920–1929,” The Journal of African American History 100, no. 3 (2015).

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays & Speeches by Audre Lorde (New York: Random House, 2007), 57; Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives , 143. I theorized resistive desires from conversations with Aimee Meredith Cox.

- Cathy J. Cohen, “Deviance as Resistance: A New Research Agenda for the Study of Black Politics,” Du Bois Review 1, no. 1 (March 2004): 30.

- Cohen, “Deviance as Resistance”; Cathy J. Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ vol. 3, no. 4 (May 1997): 437–465; Hortense J. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 64–81; Haley, No Mercy Here; Treva Carrie Ellison, “Black Femme Praxis and the Promise of Black Gender,” Black Scholar 49, no. 1 (2019); Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy . Jacquelyn Dowd Hall brought attention to sexual deviance in labor organizing in the context of Appalachian white women; see Hall, “Disorderly Women,” 374–376.