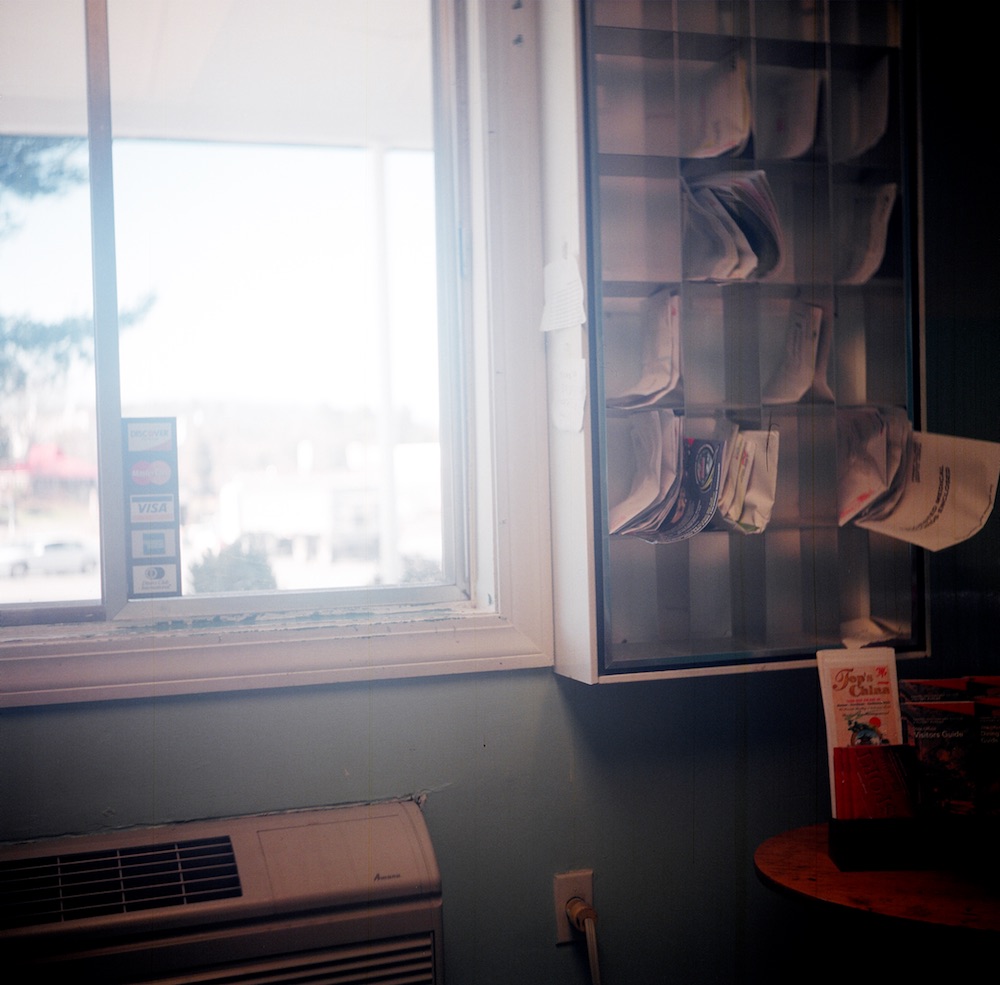

“There’s an unsettledness that attracted me to these spaces, that maybe draws in people of a wandering sort, but it doesn’t allow for getting too attached.”

From 2005 to 2007, I used a Rolleicord twin lens reflex to photograph RV parks across North Carolina, making color landscapes and portraits to document a vanishing world. I found these hidden landscapes in often unseen communities that exist behind doomed shopping centers, just off the side of the busy interstate, on the sharply bending curve of a mountain road: clusters of shiny-new and rusted-fading campers, with stark contrasts between the natural and the manufactured.

The campground is a microcosm of the outside world, each with its own rules, structure, and gathering spots. In some parks, it seems like everyone knows each other and you’ll see shared meals at the central picnic table or evening beers and a boom box playing by the firepit in front of the “party camper.” In others, no one knows their neighbors and suspicion takes the place of community. It gets quiet after dark and you only hear private murmurings floating in stereo in the night air around you.

I wanted to photograph the unexpected beauty of the RV terrain and the inhabitants whom I imagined ditching their day jobs, going off the grid to live on their own terms, drawn together by a shared way of living. What I often found instead were people setting up temporary spaces that turned to permanent homes when they had no other options. A family of four living in a 150-square-foot camper; a man on disability who spends eighteen-hour days selling nascar trading cards on eBay; a group of construction workers paying month-to-month while working on a building job nearby; a high school girl who wants to be an actress and study in Oxford.

I visited campgrounds on the edge of being razed to the ground to make way for new developments and parks with campers crumbling into the landscape, their owners unsure where they would go next. I attended town meetings about redevelopment and heard from residents who felt they were getting a raw deal, getting pushed out to make room for people with money.

There’s an unsettledness that attracted me to these spaces, that maybe draws in people of a wandering sort, but it doesn’t allow for getting too attached. It doesn’t allow for falling in love with a place and trying to make a home.

This photo essay was first published in the Documentary Moment Issue (vol. 26, no. 1: Spring 2020).

Joanna Welborn is a photographer from Durham, North Carolina. She makes photographs of people and landscapes to tell stories, real and imagined, using a Rolleicord, a Canon, and a small notebook. She also works for justice in agriculture at Student Action with Farmworkers.