The American South has always been a mythic land of contrast and juxtaposition—Black and white, rich and poor, mountaineer and planter, hospitality and violence, unregulated development and a sense of place, greed and grace, illiteracy and great writing—and it remains so today. One of the more intriguing paradoxes is the image of the South as the Bible Belt, a place where fundamentalist zealots constantly damn deviant behavior, and as the land of the honky-tonk, a place where good ole boys and girls push the limits of drinking, dancing, dalliance, and debauchery. In this essay, we seek the clues to that puzzle in one of the region’s principal cultural texts, the lyrics of commercial country music, and illuminate the larger social dynamic by focusing upon attitudes expressed about the pursuit of pleasures in the honky-tonks of the lyrical landscape, that liminal weekend window situated between jobs and Jesus.

Paychecks and Paternalism

Even the casual observer knows that the working poor are the predominant dramatis personae in the rhetorical vision of country music. In “Forty Hour Week,” after eulogizing an itemized who’s who of the proletariat, Alabama sings that they “work hard every day” and proclaims that the “fruits of their labor are worth more than their pay.”1 On the other hand, we found no songs that discussed the joys of the job or claimed that vocational pursuits led to the ultimate self-actualization of the individual.

Paul DiMaggio, Richard A. Peterson, and Jack Esco Jr., in their article “Country Music: Ballad of the Silent Majority” suggest that the lyrics of country music bemoan the economic structure but fall short of rejecting the system and the American Dream of achieving success through hard work.2 Two songs identified in this study seem to support their thesis. Bill Anderson’s “Laid Off” portrays the plight of a man and his wife who both lose their jobs on the same day, but says they will make it even though they will be on their knees asking the Lord to help while they are out of work.3 Merle Haggard’s “If We Make It through December” tells of a man who “can’t afford no Christmas” because, despite his diligent efforts and hard work “got laid off down at the factory.” Although he feels that “their timing’s not the greatest in the world,” he expresses hope for the future if his family can just make it through the winter.4 Haggard is less optimistic, however, in “Hungry Eyes,” in which he concludes that “another class of people put us somewhere just below,” and he laments that their prayers and hard work only brought a loss of courage.5

Hopelessness is more clearly expressed in Charley Pride’s “Down on the Farm.” He bemoans the plight of farmers who “never thought of giving it up,” but who are now “staring out a factory window,” and “trying to understand it all.” Despite their hard work they discover that “a way of life can be auctioned off.” “It was only the family farm,” they despaired, “who really cares if it’s gone.” Poignantly, Pride acknowledges that “somebody’s dreams are gone.”6 As Hank Williams Jr. sang of the situation about the banker being against the farmers, “the farmer’s against the wall.”7 John Conlee brought Harlan Howard’s classic “Busted” back on the charts in 1981; it is another song that depicts hard times, contemplates stealing to survive, and despairs of any possible solutions to the economic woes.8 Merle Haggard reaches the same conclusion in “A Working Man Can’t Get Nowhere Today.”9

Conlee’s version of “Nothing Behind You, Nothing In Sight” tells of how he sells his week to a company that uses his body and cares nothing for his mind, of the lack of hope felt when the worker knows that all his tomorrows will be just alike, of knowing that there is nothing behind him and nothing in sight “when the worries have stolen the dreams from your night.”10 Another Conlee hit, “Working Man,” echoes the same themes. He describes a working man who notes that all the other line workers have worried faces just like his, and that they are “showing the wear and tear in their eyes.” He suggests that the system itself makes it hard on a workingman who makes a living any way he can while barely existing on the installment plan.11

Conlee’s songs leave little hope for improvement and offer no solutions, and McGuffey Lane’s “Making a Living’s Been Killing Me” also rejects the dream without satisfactorily resolving the dilemma. He is being underpaid for overtimework, and the money he is paid cannot buy any peace of mind. The frustration is compounded when the foreman tells him that three hundred more will be laid off in the near future, when he probably will be waiting his turn in the unemployment line. Lane also introduces the element described earlier by Paycheck and others, that the people at the top of the ladder are becoming richer while those at the bottom pay the taxes and have less than they need to survive.12

Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5” is perhaps the best known song in this genre. While the movie and television series portray burdened secretaries in corporate offices, people in other occupations also identify with the lyrics. Parton reinforces the idea that the worker is barely surviving while employers are always taking. Unlike the man in Conlee’s song, she suggests that they do use the worker’s mind but do not give them credit for what they produce and that this will “drive you crazy if you let it.” The lyrics blame management: “They let you dream just to watch them shatter.” Ultimate fault, however, is found with the system: “It’s a rich man’s game,” Parton sings, “no matter what they call it.”13

Some lyrics openly express resentment toward “the system.” In one song a man convicted of murder admits his failure in society and in his personal life but proudly boasts, “I Never Picked Cotton.”14 McGuffey Lane’s hero in “Making a Living’s Been Killing Me” decides to quit his job and go “where it don’t make a damn what the boss man says,” and Johnny Paycheck’s “Take This Job and Shove It” expresses a similar disdain for the degrading system and his superiors.15 Other songs go even further, questioning the underlying values of the American Dream itself. For example, Loretta Lynn’s “Success” discusses the damage done to a personal relationship by a husband’s pursuit of the dream. A related theme is also raised in the chorus of Hank Williams Jr.’s “American Dream,” in which he questions whether we want or really need that dream of success because it makes people crazy by raising unrealistic expectations.16

Certainly their position in the working class makes southerners constantly aware of economic constraints and the necessity to work at often unfulfilling jobs. But any assumptions about their dedication to the economic system and their uncritical acceptance of the “work ethic” must be tempered by an acknowledgment that country music texts raise serious questions about the fundamental fairness of the economic system. This view of the weekday routine that structures most of life also gives added significance to the weekends, those free spaces where individuals have some control over the expressive behaviors in which they will participate.

Sunday Services

Country music lyrics treat another dimension of the regional culture that traditionally has been thought of to shape the southerners’ view of the world. The pervasiveness of Protestant religion in the South and the social pressures to participate influence the presumption that church membership and attendance are completely voluntary actions consciously chosen by the participants. Of course, many southerners value religion, as popular country music lyrics attest.17 Shenandoah sings of “Sunday in the South,” noting the local congregation’s integral role in the regional culture, and even Charlie Daniels, caustic critic of television preachers, sings that many of the world’s ills can be attributed to the fact that “people done gone and put their Bibles away.”18 As we have argued elsewhere, country music reveals a much more sophisticated assessment of the role of religion than the conclusions to be drawn from simple regional stereotypes.19

Echoing the perceptions of an unfair economic structure that rewards the unworthy, a more common theme in recent country lyrics is that modern televangelists are more interested in collecting and storing up treasures on earth than in advancing any religious teaching. In “Praise the Lord and Send Me the Money,” the lyrics describe an unfortunate response that occurred when a listener became disoriented after being exposed to the standard appeal. As the man in the song tells it, he dozed off on the couch and was awakened by the voice of a preacher on television exhorting listeners to praise the Lord and send the money. Thinking it was a vision and “trembling with guilt,” the man wrote a check for $10,000 and mailed it to the preacher who insisted that Jesus desperately needed the money. The next day he realized he had written a hot check to Jesus. Rather than let the check bounce, he took a second job in a gasoline station in order to pay the debt and attempt to be as happy as the man on the television.20

Other songwriters react more critically and perceptively. Charlie Daniels identifies television ministers as one group seeking to control the free thinking and free living person he wished to be. In “Long Haired Country Boy,” Daniels attacks the major flaw in television evangelism: hypocrisy. The man in this song also describes a “preacher man” on television who was seeking a donation “‘cause he’s worried about my soul.”21 Hank Williams Jr. assails the money-raising tactics of the electronic ministry in “The American Dream.” Williams criticizes the preachers’ hidden motives and their persuasive appeals used to secure money, noting, that though they want you to send your money to the Lord, “they give you their address.”22 Bobby Bare employs satire to critique the phenomenon in “Drinkin’, Druggin’ and Watchin’ TV,” demonstrating the almost casual consumption of the medium, suggesting that the preacher might hold some unstated power over non-believers and observing that a couple thinks they are going to hell “making love with the sound off the P.T.L.”23

The above musical commentaries anticipated the fall of the mighty in 1987. The six million dollar evangelical extortion of holy hostage Oral Roberts, the P.T.L. financial felonies, and the sexual sleaziness of televangelists Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart undermined public support among the formerly faithful viewers and contributors that spring.24 Nowhere was the impact greater or more noticeable than in the South, and Jerry Falwell lamented, “I don’t ever remember a time when people driving trucks, talking on CBs, and sitting in restaurants were having such a heyday ridiculing all that is Christian.” An equally perverse and pervasive message was dominating the country format radio stations across the South, including such titles as “The P.T.L. Has Gone to Hell, So Where Do I Send the Money?” by Rev. Needmore and the Almighty Bucks and “Poverty-Stricken TV Christian” by Bobby Goodman.25 The most requested song on many country stations was Ray Stevens’s “Would Jesus Wear a Rolex?” Ray Stevens’s narrative seems to have given voice to the thinking of many southerners as he ridiculed the televangelists who asked for donations from the common folks while wearing designer clothes and expensive jewelry, driving fancy cars, and owning palatial homes in Palm Springs. Joe Gatlin, station manager at country station WKNZ in Collins, Mississippi, said his station responded to overwhelming requests by playing it every hour and a half. “What’s funny is this is the Southern Baptist Belt, yet I think people love this song,” he said. “I think a lot have come to realize over the years that what the song says is true.”26 The persuasive power of the enthymeme works because the audience already holds the premise and providesthe conclusion.

Despite the sometimes cynical assessments of organized religion and its agents, the message in the country music lyrics should not necessarily be interpreted as overtly anti-religious. Singers and songwriters of commercial country music are following a well-established tradition when they debunk the messengers and channels rather than the religious message. One of the prevailing characteristics of commercial country music is the lack of faith in institutions—whether political, economic, social, or religious.27 The institutions are generally mistrusted; those who assume or exercise power are frequently held in low esteem.

Although country music lyrics generally celebrate the religious experience, many songs object to the hypocrisy of traditional institutions just as strongly as they do that of the modern electronic church. “The Outlaw’s Prayer” describes how a picker is ushered out of church because of his big black hat, long hair, and a beard. Sitting on the curb outside the inhospitable church, he talks directly to God and questions the actions and attitudes of the congregation. For instance, he observes a wino across the street and laments that money spent on one stained glass window in their building could feed that man’s family for years. The picker also speculates that John the Baptist and Jesus would be unwelcome due to this group’s dress code. Paycheck concludes his prayer by observing that if God plans to take the congregation to His kingdom, then he is not particularly interested in going along.28 As Don Williams sings in “I Believe in You,” most southerners “don’t believe that heaven waits for only those who congregate.”29

Among the particular targets of country critics are those members of the congregation who are quick to judge those whom they believe less worthy. “Mississippi Squirrel Revival” relates the antics of a crazy rodent turned loose in the “First Self-Righteous Church” of Pascagoula, Mississippi, stripping the facade of piety from “Sister Bertha Better-Than-You” and others among the flock.30 A Sunday school teacher is confronted in “The Lord Knows I’m Drinking” when a man sitting in a bar with a drink and a young woman (who is not his wife) is accosted by a female member of the church. He calls the intruder, among other things, a “self-righteous biddy” and tells her that if she is not too offensive he will put in a good word for her later on that night when he talks personally with God.31 The so-called Christians, who make a great effort and demonstration on the Sabbath and turn their backs on the religious precepts during the remainder of the week, are chastised in “Sunday Morning Christian” and warned in “Your Credit Card Won’t Get You Into Heaven.”32 In “Trip To Hyden” the singer describes the desolate and forbidding environment of a coal mining town and observes signs proclaiming that Christ is coming: “And I thought, ‘Well, man, he’d sure be disappointed if He did.'”33

The real heroes in these narratives are more likely to be the “lower sort,” marginalized individuals who enact Christian principles in their daily lives. For example, in “The Gospel According to Luke,” a down-and-outer says, “give to your brother if he is in need,” and then demonstrates his faith by sharing the change he had collected with those less resourceful.34 In “Northeast Arkansas Mississippi County Bootlegger,” the “deacons and their ladies” scorn the bootlegger’s family, that is until they need money for a new sanctuary and find their manna comes from mash.35

Country music reflects a strong sense of individualism and opposition to hierarchy among southerners, in religion as well as in other social and economic relationships. Historically, notes Donald Mathews, “Among the religious themselves, isolated, uneducated, and relatively powerless whites would often complain about the aloofness of denominational authorities and resist as best they could the professionalization of the clergy.” If they had to have any minister, he says, they “preferred to have leaders who could identify with them and evoke the cathartic and healing ritual of self-discovery and forgiveness, rather than clergymen who would preach careful sermons of correct understanding and refined sentiments.”36

Therefore, it is not surprising to find so little adoration and adulation in the lyrics for the professional brokers of religion. The listeners desire the personal benefits promised by religion just as they wish to have the financial benefits of the economic system, yet they resent those who seek to limit or control the distribution of both spiritual and financial resources. Clergy and congregation both represent forces that monitor individual expressiveness and attempt to repress the individual pursuit of pleasure. Ministers and self-righteous church members are ridiculed and parodied in country music lyrics with the same strategies used to depict corporate executives and line bosses. In both cases laughter provides distance and space for those engaging in it, and that space provides at least an illusion of personal freedom not otherwise socially sanctioned or readily available.

Honky-Tonk Heaven

In the world portrayed by country music lyrics, Saturday (actually beginning, much like the Jewish Sabbath, at quitting time on Friday afternoon) is the High Holy Day of expressive culture, a time when individuals are free to engage in “those activities not primarily concerned with ‘instrumental,’ goal-oriented behavior related to earning a living.”38 That is, they act as they please, free from the demands of weekday work, the constant responsibilities of family and home, and the religious requirement of Sunday services.

Saturdays have been different from the rest of the week, at least since time was measured in seven-day periods, but for different reasons. First, as the seventh day, it had religious significance, a sacred time of rest and worship distinct from the other six devoted to profane work. Later, the day of rest had economic utility and was allowed so workers could recover and return to work refreshed. Saturday nights, however, have had an especially distinguished history. Susan Orlean’s view, which supports the argument of this study, is that Saturday nights are a time of expressive freedom and of intense passion for life unlike the supervised and structured spaces in contemporary southern culture. “For most people Saturday is the one night that neither follows nor precedes work, when they expect to have a nice time, when they want to be with their friends and lovers and not with their parents, bosses, employees, teachers, landlords, or relatives—unless those categories happen to include friends or lovers,” she says. “Saturday night is when you want to do what you want to do and not what you have to do. In the extreme this leads to what I think of as the Fun Imperative, the sensation that a Saturday night not devoted to having a good time is a major human failure and possible evidence of a character flaw.”39

Saturday night is also prime time for living in the lyrics of country music. In a song entitled “Livin’ for Saturday Night,” John Schneider gives voice to the thoughts of many in the country music audience. He complains of working five hard days at the “same old grind,” where he has “too much work” and no time for himself. All week long he has done what he’s “supposed to” and had no chance to be himself. Now that the weekend has arrived, he is looking forward to the “good times” with “music and neon,” knowing that he will soon “be on top of the world feeling right.”40

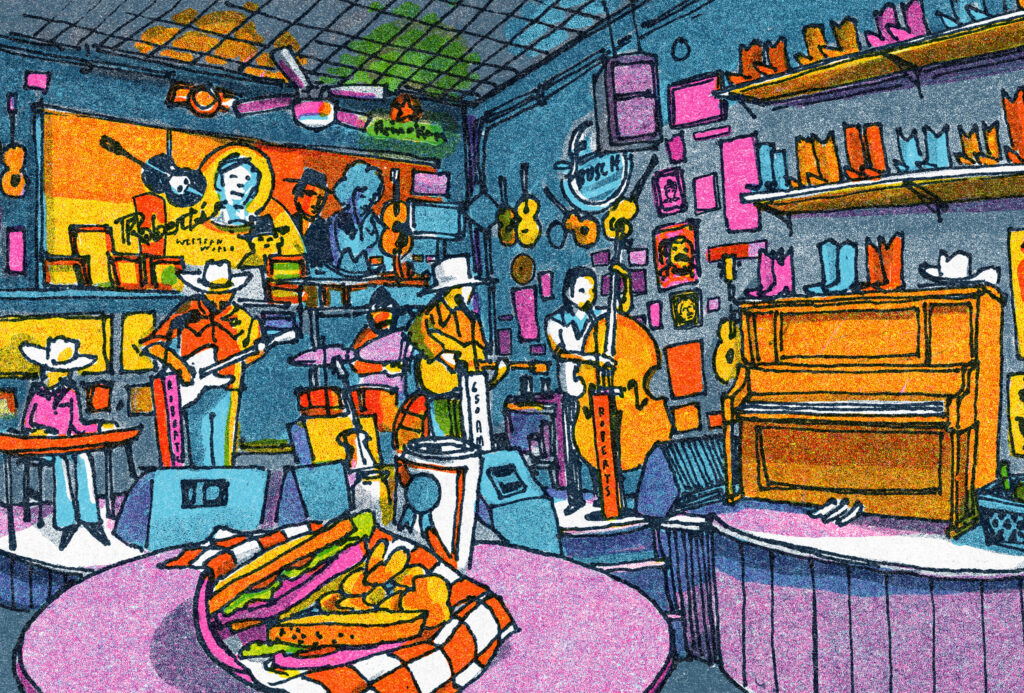

For the characters in country music lyrics, the honky-tonk is the primary scene for staging the Saturday night drama, leading Carol Offen to call it “the hillbilly shrine,” a “smoky kingdom that beckons with loud music, ‘cigarettes, whiskey, and wild wild women.'”41 In effect, the honky-tonk is like a secular temple for the expressive ritual, where the bartender becomes the confessor, the bouncers act as ushers, sacramental beer and wine prepare customers for the nocturnal quest, and the juke box becomes the organ for loud music, distinguishing the noise of the profane world from the traditional silence of the sacred.

Neither the fields of cotton nor the fields of the Lord offer such respite. If the factory and the church are the architectural places of work and religion, the honky-tonk is a “safe house” where the weekend customers can find true sanctuary and escape the pressures of their world. One singer claims in “Honky-Tonk Amnesia” that in the evening he can forget the constraints of marriage and in the morning forget where he’s been and what he’s done.42 In “Honky-Tonk Moon” the singer finds that the smoke, the neon, and the music of the honky-tonk provide a place where his “troubles seem to melt away” in the night because “there’s no hurry, no worry” and he’s easy in his soul.43 A similar situational relief is found by the singer in “Honky-Tonk Crowd,” who claims that the music makes him happy, that people treat him right, and that he has a sense of belonging.44

A combination of social forces and individual urges helped to create the atmosphere that spawned honky-tonks in the South.45 The honky-tonk is a liminal place just on the outskirts of town that serves as both sanctuary and staging area for those who wish to be alone or in a crowd away from the home, job, or church. Urban Cowboy depicts a dance hall that hardly resembles a typical honky-tonk any more than the featured music is real country. True honky-tonks have concrete walls. Outside, there are only vague limits to parking areas, and a burn bin serves to destroy the evidence of a tawdry night out. Modern restrictions such as building codes, zoning regulations, availability of parking spaces, exhaust systems, and fire codes are not primary concerns. Something to keep the weather out and the participants in does nicely. The paces are halfway houses where a few of the rowdier participants might awaken on an early Sunday morning, a working class sanctuary with a lot of stains but few glass windows.

Most regulars in a honky-tonk know that it can be either a blessing or a curse. People who work hard for their money a hospitable place to spend it; those who feel stifled at home or work a place to unwind, and for those who are constantly assured of the certainty of hell, may find it’s the closest thing to heaven they will ever see. The honky-tonk provides the elusive but temporary relief from the restrictions found at home, work, and church. Unless an active participant in this outlandish scene, a mother, lover, boss, or preacher has considerably less control.

The suspension of ordinary “city limit” rules or regulations in the honky-tonk does not mean that it is totally free of restrictions; however, violating written or unwritten rules there can have fewer consequences than breaking codes in real life. Residents of that loud, smoky kingdom are usually more forgiving than a momma, a boss, or a preacher might be. Buddies who drink together tend to hang together—if they can remember to do it—and are generous in cutting slack. Aaron Tippin describes a man who is a model employee down at the factory five days a week, but on the weekend he turns into a “Honky-Tonk Superman.” He takes pride in his record at work and the feats he accomplishes in the bar. Although most objective observers might be able to see the hazards created by the mild mannered factory worker, he is only slightly chastised by his favorite waitress when she tells him he should not have roller skated down the bar.46

The secular salvation offered by the honky-tonk is articulated in the lyrical catechism of country music. In “Honky-Tonk Stuff” the singer says he works “like a dog all day” but is ready to roar “all night to the morning light” at the honky-tonk because he loves the music, the wine, and “chasing that honky-tonk stuff.”47 Similarly, in “Honky-Tonk Man,” the storyteller claims to be “livin’ fast and dangerously” after sundown, finding inspiration in “the music of an old juke box” and seeking “a purty little gal and a jug of wine.”48 The charts are flush with hits bearing such titles as “Honky-Tonk Wine,” “Honky-Tonk Women,” “Honky-Tonk Women Love Redneck Men,” “Honky-Tonk Women Make Honky-Tonk Men,” and “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels.”49 Yes, sinners, it is a religious experience!

Metaphorically the honky-tonk becomes a shelter for the homeless. Such a place is often damned by preachers and partners who have been wronged by a loved one who finds this home away from home. Tracy Lawrence tells how he once called “the honky-tonk on the edge of town” his second home. After a fight, his significant other tells him “Your second home just became your first.”50 Responding differently to a similar situation, another woman who wanted her man at home says, “I’m Gonna Hire a Wino to Decorate Our Home” in the style of a honky-tonk.51

Hank Williams Jr. suggests “Honky-Tonkin”‘ as a solution for the “sad and lonely” with no place to go—a temporary but practical solution to anomie that eluded both Comte and Durkheim.52 In “Honky-Tonk Heroes (Like Me),” Billy Joe Shaver found a perfect haven for “lovable losers, no account boozers, and honky-tonk heroes like me.”53 Assessing the attraction of the honky-tonk for the disaffected, Offen suggests:

Some people are lured by the excitement and hint of romance, others by the chance to lose themselves in the din of other people’s revelry. The seedy, often back-street hangout is very much a man’s domain, a place where he can escape temporarily from an unhappy home, a wearing job. Here, he can be his own man. There are no bosses among drinking buddies. He finds some “wild women,” of course, but the most compelling companionship to be found there is in the bottle. While drugs have long been an integral part of rock music, liquor still dominates the honky-tonk scene, perhaps because of its communal, extroverted effect. Instead of withdrawing into themselves, hillbillies are most likely to drown their troubles in a roaring, all-night bender.54

Music, and we mean country music, has an even more important func- tion in the honky-tonk than it does in church services. The lyrics provide back- ground for dancing and singing along, not unlike hymns in religious services, and the messages become equipment for living, scripts for acting. But the fans, writers, and singers of country music focus much more attention on the jukebox than on the church organ. Some personify the jukebox and include it on the short list of loved ones. Mark Chesnutt, for example, lists mother freedom, father time, brother jukebox, and sister wine as all the family he has left after his lover has gone.55 In another Chesnutt song, “Bubba Shot the Jukebox,” a man who “was never accused of being mentally stable” hears a particularly sad song, goes to his truck, gets his gun, and puts an end to the song’s and his misery. After he has fired the fatal shot, Bubba sits down and waits for the local sheriff.56 Just as they are a real part of life, jukeboxes can also play a part in the sacrament of death. Doug Supernaw used one as a tombstone for a dedicated fan in “Honky-Tonkin’ Fool.” The fool in the song had attacked the poor quality of modern day country songs and believed in the power of a traditional one, when he makes a strange request. He asked that upon his death, his young friend place his favorite jukebox on his grave and fix it to play “Your Cheatin’ Heart.”57 Joe Diffie describes another man who, wishing that the good times would never end, requests that upon his death he be propped up by the jukebox with a strong drink in his hand.58

The man or woman who drinks and deserts the faithful sober one at home has always been a common refrain. In recent years, more unusual themes have appeared. A gay man in drag serves as the object of a good ole boy’s refracted attention in Moe Bandy’s and Joe Stampley’s “Honky-Tonk Queen.”59

More importantly, the lyrics depict a variety of roles for the independent woman in a honky-tonk environment. In earlier songs, women are usually the ones who welcome the old boy to a world with more attractions and fewer restrictions than those at home. This situation is exemplified by the barmaid in Conway Twitty’s “There’s a Honky-Tonk Angel (Who’ll Take Me Back In).”60 But women now behave more like the men who hang out in bars to drink and just to be alone. The woman in Lorri Morgan’s “What Part of No” puts down a man who is attempting to take her away from all that. The woman reduces her rejection to one of the smallest words a man can comprehend and then asks what part of that word he does he not understand.61 Other songs speak with a moreambivalent voice. A man in one of John Anderson’s songs tells another he had better examine the woman’s choice of drink before attempting to start a conversation. If drinking wine, she will welcome dancing and having a good time; but, if she is drinking tequila, the fellow should come up with another idea.62

The receptive, if hesitant, woman pictured in many songs of the past is nowhere to be found in other songs. Shelly West’s version of “Jose Cuervo” indicates the different effect of tequila: the next day she asks whether she danced on the tables or shot out the lights.63 Lari White also sings about a woman who stays too long in a bar and deals with a proposition she ought to refuse. Instead, she tells the man not to try to lead her into temptation because she already knows the way. All he has to do is get behind her, and she will take him down that familiar path of temptation high on the list of those matters the preacher will take up the next day.64

Such a response should not be surprising when one considers the pressure and stress endured by the socially and economically marginalized men and women portrayed in country songs and those constituting the primary audience for such music. The repression of the laborers’ fundamental id impulses by the implicit superego inherent in a hierarchically-organized society—the weekday demands of the boss on the job Monday through Friday, the responsibilities of home and family, and the Sunday scolding of the preacher—finds relief on Saturday night when the repressed returns with a compensatory vengeance.65

Conclusions

For the characters in the narrative reality of country music, Saturdays nights are prime time for raising hell. Much like the Bakhtinian notion of Rabelais’ “carnival”—when the serfs and peasants could engage in revelry and ribaldry, mocking the powerful and temporarily suspending the oppression of church and commerce—Saturday night is the time for honky-tonking. The normal rules of civil behavior do not apply, and the participants in the social dream world can restage, confront, and overcome the traumas of everyday life.66 Facing days full of uncertainty and having virtually no opportunity to control the events affecting their own lives, they reject passive fatalism and actively seek excitement on their own terms. Drinking and dancing, fighting and fornicating, fast horses and faster horseplay—those expressive activities normally repressed by the power of bosses, preachers, and family members—are the order of the night.

Country music lyrics provide a unique insight behind the surface contradictions of contemporary southern culture. Lyrics have shown that beneath the fascination with the regional stereotypes and the search for the “mind” of the South, communication research can illuminate the subconscious mind and the “soul” of the South. There, the work ethic is undermined by an almost Marxian resentment about the pressures of the job and the control of the bosses seen as inherent in the hierarchy of the system. The southerner’s outward devotion to religion is countered by ridicule of the perceived hypocrisy in organized religion, allowing personal freedom from external censure without denying the spirituality of individuals.

In such a culture, imbued with economic and social controls, it should not be surprising to find, as we discovered, that in the “free space” for “expressive culture”—Saturday night—the actors in this drama choose to retreat to the honky-tonk, where the shackles of work are lifted, the bonds of matrimony are loosened, and the oppressive moral restrictions of the church are vigorously ignored. One singer proclaims in “Honky-Tonk Crazy,” “I only feel right doin’ wrong,” and these ritual “transgressions” become symbolic acts of self-empowerment.67 The cultural contradictions are not necessarily resolved by this rhetorical analysis, but the oppositional behaviors within the cultural context can be understood as narratively logical reactions to coercive social pressures and repressions.

The music continues to change to fit the changing environment of the honky-tonk.68 Cheatin’, hurtin’ love, and lifestyle songs (songs depicting the way the folks in the honky-tonks have lived, are living, or wish to live) became staples for the audiences, whether delivered by live bands or jukeboxes. The music spread from those places and at one time was extremely popular with those that may not have known a honky-tonk from a small church. Although the “classic” period for honky-tonk music has passed, current country music still speaks of the milieu. For instance, five of the top fifty songs in 1993 praised honky-tonks.69

Limiting our examination to a particular genre of musical texts, country music lyrics, arguably restricts the generalizability of our analysis primarily to the white subculture that constitutes most of the country music audience and the population of the South. The rich lyrics of blues, gospel, soul, and rap lyrics could well reflect similar attitudes among African American audiences, another marginalized group in contemporary American culture. In both cases, however, it might also be argued that the studies of the texts valued by marginalized groups can tell us much about the collective psyche of the larger culture. Exaggerated stereotypes of marginalized subcultures make them delegate groups that “act out for the larger group the extremes of individualism and conformism, out-of-con-trol and control, rebellion and submission, acting out and repression, isolation and community, competition and cooperation, self-expression and consensus, mobility and settledness, discharge of rage and denial of aggressive impulses, and psychopathy and hysteria.”70

May the jukebox blare on, bellowing out and sounding off about corporate insensitivity, phony religion, lost love, honky-tonkin’, and, ultimately, the human experience. Amen.

“Country’s Cool Again”:

An SC Music Reader

Fifteen essays, old and new, curated by Amanda Matínez. Read the full collection >>

Jimmie N. Rogers was the chair of the communications department at University of Arkansas. He did extensive research, lecturing, and writing on the content of country songs.

Stephen A. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He lives in Southern Pines, NC, and often contributes to to PineStraw, Walter, and O. Henry magazines.

Header image: Honky Tonk, by Tim Vrtiska, July 30, 2016. Flickr.com, CC BY-ND 2.0.

NOTES

- Alabama, “Forty Hour Week (For a Livin’),” RCA 10485, 1985.

- Paul DiMaggio, Richard A. Peterson, and Jack Esco Jr., “Country Music: Ballad of the Silent Majority,” in The Sounds of Social Change, ed. R. Serge Denisoff and Richard A. Patterson (Rand McNaIIy, 1972), 38-55.

- Bill Anderson, “Laid Off,” Southern Tracks 1011, 1982.

- Merle Haggard, “If We Make It through December,” Capitol 3641, 1973.

- Merle Haggard, “Hungry Eyes,” Capitol 2383, 1968.

- Charley Pride, “Down on the Farm,” RCA 14045, 1985.

- Hank Williams Jr., “I’m For Love,” Warner/Curb 29022, 1985.

- John Conlee, “Busted,” MCA 52008, 1981.

- Merle Haggard, “A Working Man Can’t Get Nowhere Today,” Capitol 4477, 1977.

- John Conlee, “Nothing Behind You, Nothing In Sight,” MCA 52070, 1982.

- John Conlee, “Working Man,” MCA 52543, 1985.

- McGuffey Lane, “Making a Living’s Been Killing Me,” Atlantic 52070, 1982.

- Dolly Parton, “9 to 5,” RCA 12133, 1980.

- Roy Clark, “I Never Picked Cotton,” Dot 17349, 1970.

- McGuffey Lane, “Making a Living’s Been Killing Me,” Atlantic 52070, 1982; and Johnny Paycheck, “Take This Job and Shove It,” Epic 50469, 1977.

- Loretta Lynn, “Success,” Decca 31384, 1962; and Hank Williams Jr., “American Dream,” Elektra/Curb 59960, 1982.

- FryeGaillard, WatermelonWine:TheSpiritofCountryMusic(St.Martin’sPress, 1978).

- Shenandoah, “Sunday in the South,” Columbia 38-68892, 1989; and Charlie Daniels, “Simple Man,” Epic 73030, 1989.

- Jimmie N. Rogers and Stephen A. Smith, “Country Music and Organized Religion,” in All That Glitters: Country Music in America, ed. George H. Lewis (Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1993), 270-84.

- Bobby Bare, “Praise the Lord and Send Me the Money,” Columbia 03334, 1982.

- Charlie Daniels, “Long Haired Country Boy,” Epic 5084-5, 1980.

- Hank Williams Jr., “The American Dream,” Electra/Curb 69960, 1982.

- Bobby Bare, “Drinkin’, Druggin’ and Watchin’ TV,” Drunk and Crazy, Columbia JC 36785, 1980.

- “The Gallup Poll: Public Loses Faith in Televangelists,” Arkansas Gazette, 23 May 1987.

- William E. Schmidt, “TV Ministry Scandals Lampooned in South,” The New York Times, 2 May 1987.

- Ray Stevens, “Would Jesus Wear a Rolex,” MCA 53101, 1987; and Schmidt, “TV Ministry.”

- Stephen A. Smith and Jimmie N. Rogers, “Political Culture and the Rhetoric of Country Music: A Revisionist Interpretation,” in Politics in Familiar Contexts: Projecting Politics Through Popular Media, ed. Robert L. Savage and Dan Nimmo (Ablex, 1990), 185-98.

- Johnny Paycheck, “The Outlaw’s Prayer,” Epic 8-50655, 1978.

- Don Williams, “I Believe in You,” MCA 41303, 1980.

- Ray Stevens, “Mississippi Squirrel Revival,” MCA 52492, 1984.

- CaI Smith, “The Lord Knows I’m Drinking,” Decca 33040, 1972.

- CaI Smith, “Sunday Morning Christian,” Jason’s Farm, MCA 2172, 1972; and Bobby Bare, “Your Credit Card Won’t Get You Into Heaven,” Drunk and Crazy, Columbia JC 36785, 1980.

- Tom T. Hall, “Trip to Hyden,” In Search of a Song, Mercury SR 61350, 1971.

- Skip Ewing, “The Gospel According to Luke,” MCA 53481, 1989.

- Kenny Price, “Northeast Arkansas Mississippi County Bootlegger,” RCA 9787, 1969.

- Donald G. Mathews, Religion in the Old South (University of Chicago Press, 1977), 240.

- Ibid., 241.

- Howard F. Stein, The Psychoanthropology ofAmerican Culture (Psycholhistory Press, 1985), 27.

- Saturday Night (Knopf, 1990) xvi, xiii.

- This recording is unavailable; however, the lyrics for this song are printed in Country Song Roundup, May 1983, 22.

- Carol Offen, Country Music: The Poetry (Ballantine, 1977), 48.

- Moe Bandy, “Honky-Tonk Amnesia,” GRC 2024, 1974.

- Randy Travis, “Honky-Tonk Moon,” Warner 27833, 1988.

- John Anderson, “Honky-Tonk Crowd,” Warner 28639, 1986.

- For a brief description of the honky-tonks and the music that bears the same name, see Dorothy Hortsman, Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy, rev. ed. (Country Music Foundation Press, 1986), 211-14.

- Aaron Tippin, “Honky-Tonk Superman,” RCA 62755, 1993.

- Jerry Lee Lewis, “Honky-Tonk Stuff,” Elektra 46642, 1980.

- Dwight Yoakam, “Honky-Tonk Man,” Reprise 28793, 1986.

- Wayne Kemp, “Honky-Tonk Wine,” Decca 40019, 1973; Charlie Walker, “Honky-Tonk Women,” Epic 10565, 1970; Jerry Jaye, “Honky-Tonk Women Love Redneck Men,” Hi 2310, 1976; Craig Dillingham, “Honky-Tonk Women Make Honky-Tonk Men,” MCA/Curb 52352, 1984; and Kitty Wells, “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels,” Decca 28232, 1952.

- Tracy Lawrence, “Second Home,” Atlantic, 87313, 1993.

- David Frizzell, “I’m Gonna Hire a Wino to Decorate Our Home,” Warner 50063, 1982.

- Hank Williams Jr., “Honky-Tonkin’,” Elektra 47462, 1982.

- Offen, Country Music: The Poetry, 60

- Ibid.

- Mark Chesnutt, “Brother Jukebox,” MCA 53965, 1990.

- Mark Chesnutt, “Bubba Shot the Jukebox,” MCA 54471, 1992.

- Doug Supernaw, “Honk Tonkin’ Fool,” BNA 62432, 1993.

- Joe Diffie, “Prop Me Up By The Jukebox (If I Die),” Epic 77071, 1993.

- Moe Bandy and Joe Stampley, “Honky-Tonk Queen,” Columbia 02198, 1981.

- Conway Twitty, “There’s a Honky-Tonk Angel (Who’ll Take Me Back In)” MCA 40173, 1993.

- Lorn Morgan, “What Part of No,” BNA 62414, 1992.

- John Anderson, “Straight Tequila Night,” BNA 62140, 1991.

- Shelly West, “Jose Cuervo,” Warner 29778, 1982.

- Lari White, “Lead Me Not,” RCA 6251, 1993.

- Sigmund Freud, Civilization and its Discontents (Doubleday Anchor, 1958).

- Mikhail M. Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Helene Iswolsky (MIT Press, 1968; and Sam Kinser, Rabelais’ Carnival: Text, Content, and Metatext (University of California Press, 1990).

- Gene Watson, “Honky-Tonk Crazy,” Epic 06987, 1987; see Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (Cornell University Press, 1986).

- Bill C. Malone, Country Music U.S.A., rev. ed. (University of Texas Press, 1985), 154.

- “The Year in Music,” Billboard, 25 December 1993, YE-35.

- Stein, The Psychoanthropology ofAmerican Culture, 24.