I made these pictures with a 4×5 Horseman studio camera during the Reagan years of 1984 to about 1988, when I was fresh into pictures. View cameras have bellows and expose larger negatives than handheld cameras. The Horseman I used was designed for studio work, as opposed to other view cameras made for the field, so it was heavy and unwieldly. Its use required a kind of ritual, where to focus an image, which I saw upside down and backward on a piece of glass, I bent over with a dark cloth over my head like some nefarious personage from a medieval morality play. Once I’d arranged the composition, I’d set the f-stop and shutter speed and slide in the film holder, a contraption you loaded with two sheets of film in a darkroom prior to your outing.

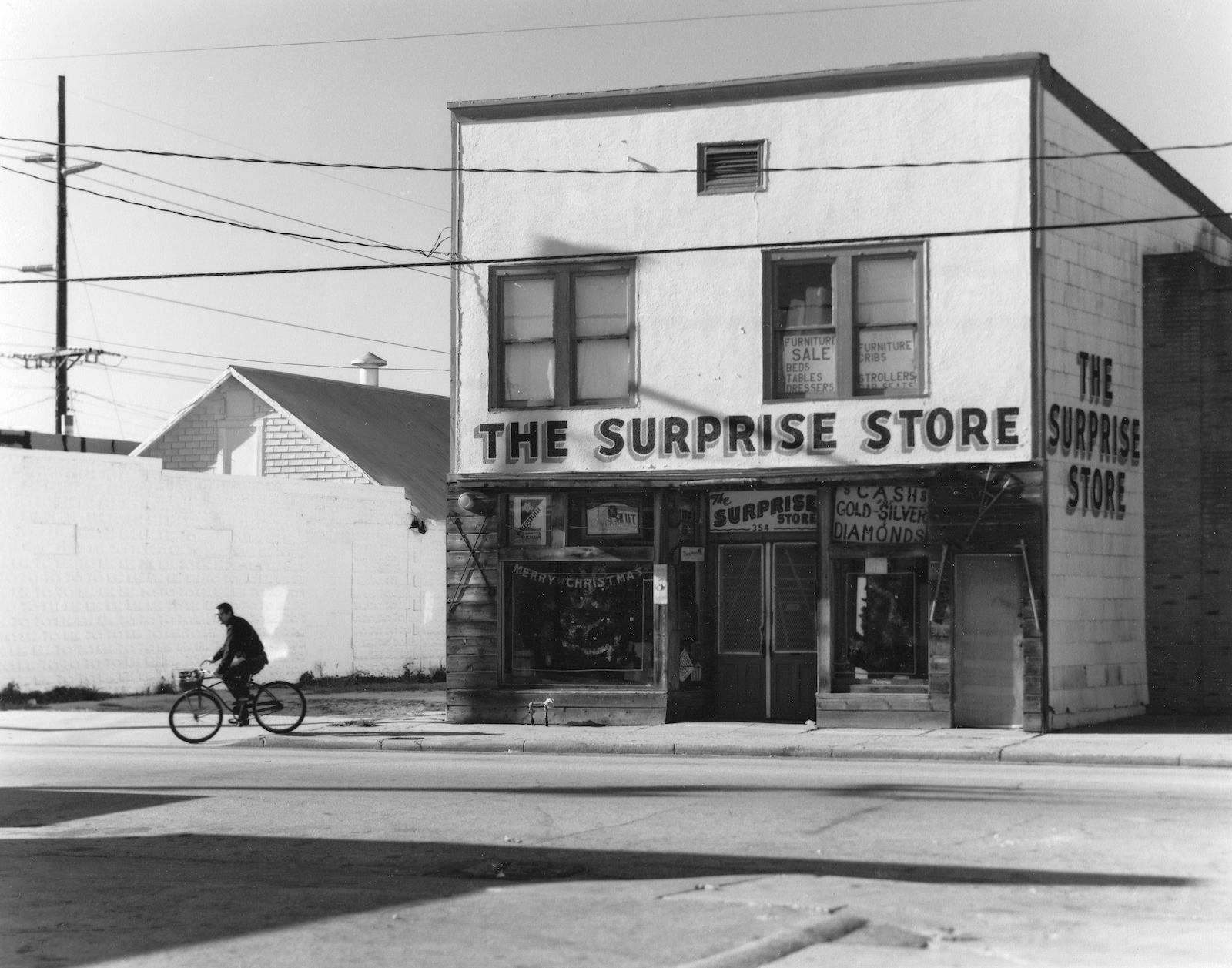

I would strap the Horseman onto the back of my motorcycle with bungee cords, along with the Gitzo tripod and a plug-in flood light, and drive around looking for people and things to photograph. (This method lasted until I had a head-on collision with a car that had turned in front of me at a busy intersection in Daytona Beach. My motorcycle was totaled, and I broke my jaw and dislocated my foot, but the Horseman held strong. From that point on, I packed my gear into the Mazda station wagon my mom gave me after the crash.) I walked rural neighborhoods with the camera attached to a studio tripod lodged against my shoulder like a grenade launcher. I knocked on doors and photographed the people inside—the people, always the people, but there were cool buildings everywhere, too, all over, and they lit up beautifully in the light, like James Agee wrote about in his great book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The things had personality, their own special kind of dead life, so what did I do? I photographed them.

I see the “southern structures” as extensions of working-class worlds that captivate me. Raised both in the South and in Mexico, the differences I saw around me resonated through a nascent sense of class and race, and, in some ways, I came to romanticize poverty. We were in Mexico so that our father, a Marxist professor, could research Mexican Anarchism after the revolution. His fight for oppressed peoples, as well as the fact that I discovered the short stories of Flannery O’Connor in high school, and later William Faulkner, may have contributed to my interest.

These experiences informed my perspective during my years with the Horseman camera. The bands I listened to in the eighties wrote songs about how awful Reagan was, the Dead Kennedys and mdc in particular. I myself was in a punk band called Hated Youth. And then there was a band called Reagan Youth, who sang, “We are the sons of Reagan, Heil!” and “The right is our religion / We’ll watch television.” When I saw the images of the Jesuit priests murdered in El Salvador in 1989, Reagan went from a kind of gratuitous whipping post to something more frightening. By this time, I was familiar, too, with the photographs Susan Meiselas had taken of war-torn El Salvador. I attended the 1988 Democratic Convention in Atlanta, where protestors emphasized Reagan’s hand in prolonging the aids epidemic. I watched the Ku Klux Klan show up and try to march. The Klan, then, seemed associated with Reagan in the same way white supremacists now seem associated with Trump.

I lucked out in my first photography teacher, Eric Breitenbach at Daytona Beach Community College, who assigned Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the southern humanist’s Bible, as reading material for his Editorial Photography course. Go to it. Do it yourself, Agee and Evans said. And as one who’d already felt the documentary impulse, I always felt as if I was preserving the appearances of a people and culture guaranteed to perish.

Breitenbach introduced me to the work of photographers that I came to admire; in particular, Bruce Davidson, Chauncey Hare, August Sander, Nicholas Nixon, Milton Rogovin, Russell Lee, and all of the Farm Security Administration photographers who shot in the documentary mode. A few appeared in Daytona for an important FSA symposium: Marion Post Wolcott, Jack Delano, Arthur Rothstein, and my favorite, Russell Lee. Lee was in his nineties, and in a private moment together I asked him if he still took photos. He said, “I’m too old,” and I didn’t understand. A talent like his, Jesus—but now I understand. Life catches up with you, and the great vision becomes heavier than the investment you put forth to live your life.

Eventually, I inched away from the documentary mode—of Danny Lyon, who I loved so much, and Robert Frank, and the Larrys, Fink and Clark, all of whom infused a personal element into their “documents.” I became interested in what happened in photographs offstage, as it were, things not seen in pictures, and how empty space made way for the imagination. I liked the weird works of Arthur Tress and Francesca Woodman. And Duane Michaels was writing on his photographs, putting in narratives. All this stuff helped pull me away from the documentary modes of photographers like Gary Winogrand and Mary Ellen Mark, as did life’s responsibilities. I had been using the insurance money I got from my motorcycle crash to fund my obsession. When the money ran out, I went back to school and began working in a new medium that was a lot cheaper: writing stories.

Give me a church with a small pointy cross on the top any day of the week. I find it elegant. Its name is Strong Lighthouse Deliverance. The sign says its pastor is A. M. Brown. Now, don’t forget to check out the reception hall. The two buildings constitute a compound, and bring to mind, for me, the kitchen houses of old plantations. In elementary school, I was told that the plantation owners had special houses for cooking so that the main house would not heat up during the summertime. In those days, there was no air conditioning.

I was driving around Jacksonville one day, and came across this awesome church called “The Church of Jesus.” I set up the Horseman, put the dark cloth over my head, adjusted the focus, inserted the plate, pulled the slide, and thumbed down the shutter release. I think Jesus would adore this church. I like the diamond-shaped door window, and the jalousies and stovepipe.

Saint Mark was associated with some kind of winged lion, but what would I have known of that back then, when I was eighteen and fresh out of a punk rock band? What I noticed were the devil’s horns up top, and the twenty-four decorative balls above the door—the balls divided into two sets, each set, I guessed, representing the twelve apostles. I wanted to know what went on in the place, so I came back on Sunday and photographed the service, wherein the talented preacher put hands on heads and screamed up in the name of Jesus, rebuking demons and healing people of sorrows and pain.

When James Agee spoke of churches in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, he spoke of symmetry and asymmetry, and used the word “façade” a lot. It was the first time I heard the word “façade.” This, I suppose, would be the side view of a church, but the façade, as you can see by looking at this picture, might not have been quite so intriguing. In the face of this church in a quiet neighborhood in Lake Mary, a town between Daytona Beach and Orlando, the elegant line of the roof would be lost, and the split made by chimney—the grace of good on one side, the tempting forces of destruction on the other.

Here, see St. Luke Missionary Baptist Church, at 4476 East Jackson Street, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003. These days, a historic plaque is stuck in the ground to its right. The pictures you find online show the building—call it an edifice—sealed from visitors. The cool bushes are gone. Stuff grows from the bricks. When people go to Marianna, it’s not salvation they’re after, it’s the Marianna caves—stalactites and stalagmites.

This is a hundred or so miles north of Cape Canaveral, and slightly east, a place a tad removed from the coast. Here, people want to get stuff started, but, hey, heartbreakers live here! Nasty Boys! Dice and $$$ and something FRESH, and it’s THE SHIT, and it’s coming soon. I did not want to leave, I tell you, but there was nobody around to stop me from going.

In Daytona I met a drunk man who’d been plant manager of Southern Bread Company. I hung out with him often in his dark apartment as he drank wine and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes, and I made an 8mm film about him. He said he’d had thirty-four women working for him at the plant. And he said that the reason he had a flat nose was because he always gave the truckers what looked to him like twenty to thirty extra loaves of bread for them to eat and give to friends. When he’d cut the stack holding the bread, the bread would fall down and break his nose. “That’s the only reason I got a flat nose,” he said. “I’ve never had it broken in a fight.”

Two graveyards were side by side. The one behind me, to the west, was the black graveyard with homemade concrete gravestones, broken bottle bits shoved into the concrete, shards to color things up nice; and little cactuses were everywhere—they stuck to your shoes and poked you as you walked around checking things out. The graveyard to the east, pictured here, was always mowed and seemed, in places, to have urns buried in the ground, as opposed to bodies. I spent hours making out with my first girlfriend back there, under the moon, wrapped up in the shadow of a cross.

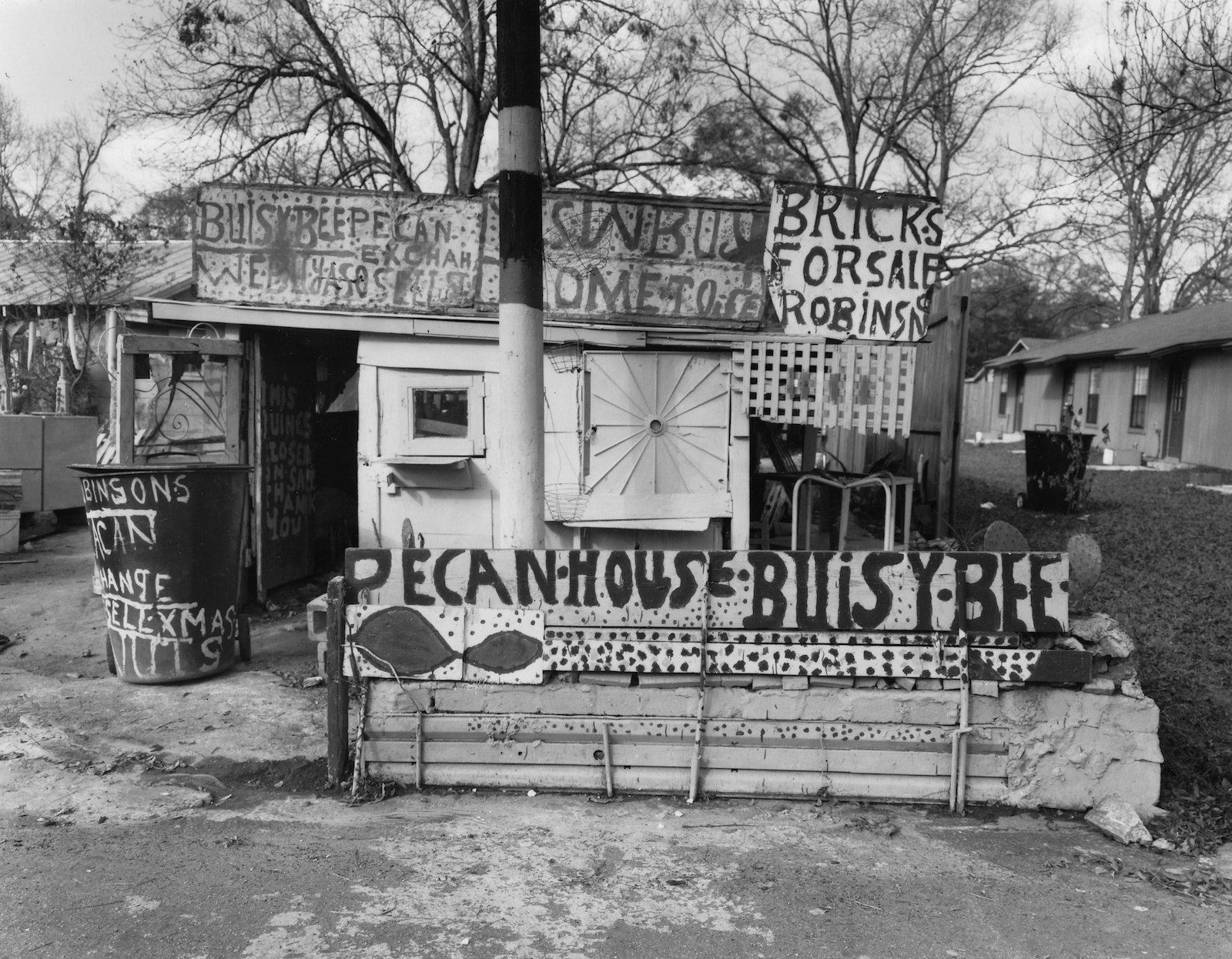

I found this building while skipping school as a teen, and met the legless bald man inside who sold pecans for a living and rolled around in a wheelchair attached to a strong dog on a chain. He lived here, straight down the hill from Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, close enough to the football field to hear the famed Rattlers marching band blowing their horns when they practiced their moves. He was skeptical of me, but let me take his picture. We didn’t talk much, but I assumed he was the sign artist. He had a good sense of composition, I thought. I liked how the cacti poking up from behind his “Buisy Bee” sign mirrored the shapes of the large pecans he painted side by side, attached at their points.

Due south of the North Florida Fairgrounds, the Capitol Drive-In Theatre, around since 1948, gave our town a mystique of the old world clashing with the new. But then it was demolished. It was replaced with an ugly, sterile, manicured reservoir. Though I never watched a movie there, a friend recalled one she watched with her grandmother and four neighborhood kids as a child. The movie, The Fool Killer, was gruesome. By the time it ended, the grandmother was so drunk that the kids had to drive home, one working the station wagon’s pedals while the other steered. I saved some of the film that I found scattered around the projectionist’s room.

I found the levees, so many sandbags piled up in a pattern as to ensure a good rampart against rising waters. I guess I could have photographed them, but what about this thing over here? Some graffiti. Evidence of life and its conundrums in a place where people were not present.

Sunland Hospital operated from 1967 to 1983. Overcrowded. Unsanitary. It was for both mentally and physically disabled people, especially kids. After the place closed down, my friends went behind the abandoned institution to get stoned, or have sex, and, later, as the place continued to deteriorate, people found ways of getting inside. I think there’d been a security guard for years, but then the city threw in the towel. I’d cut under a fence and go in and see weird stuff scrawled by children on walls, rolling tables and wheelchairs, thick vines growing through broken windows. Live vegetation spread across the hall floors, tree branches reaching in, nature trying to reclaim the place, and doing a good job of it before it was, as all things seem to be wherever people are involved, demolished.

My friend Bruce was committed to the Chattahoochee mental ward for trying to saw his hand off. I think he might have been doing the “if thy hand offend thee, cut it off” business thing from the Bible. During his time inside, about two years, I visited him now and then. After leaving him, I’d drive down the hill and pass by this building. I don’t know what it was used for.

It’s made of fiberglass. Or I don’t know for sure if it’s made of fiberglass, but I think it is. First thing you notice, I’ll guess—after you see the horse missing his right foreleg, and the cool clouds and peculiar signs—are the thingamajigs in the sky, streaks of mud. What are they? They’re streaks of Marshall’s spot tone mixed with spittle. I used the photo for testing, for getting my brush ready, a preparatory measure for the dust specs and hairs that mar my pictures. B&W photographers correct such flaws, but our views differ on technique. My best photography teacher used his tongue to get the tone right. Other photographers say that’s like spitting on your pictures, but I say, Let’s do it. Let’s spit on our photos and skip the signing.

I showed this picture to my mom. She laughed in misreading the name “Clint” as the derogative term we all know. I had not seen it till she pointed it out. I was like, Okay, well. But after that, my fondness for the photo diminished. Made it seem like that’s why I’d made the effort, but that’s how it looked is all. What had captured my attention, and had made me want to take the picture, was the rough-hewn, homemade gravestone that somebody just wrote on with a brush dipped into a little can of enamel paint, and the cool early morning shadows cast sidewise across the dappled, sacrosanct, untouchable sand that has a miniature fence around it.

This feature appears in the Winter 2018 issue (vol. 24, no. 4).

John Oliver Hodges attended the Southeast Center for Photographic Studies in Daytona Beach, and has photographed extensively in small, medium, and large formats. His works have appeared in periodicals such as Juxtapoz, Shots, and Oxford American. He is the author of three books of fiction and lives in New Jersey, where he teaches writing at Montclair State University.