“Phelps’s images hold a kind of interest and value that a stranger’s cannot.”

Editor’s Note: Since this piece was first published in 1994, the T.R. Phelps collection has moved from Emory & Henry College back to private ownership. The work of T.R. Phelps still remains largely untapped by scholars.

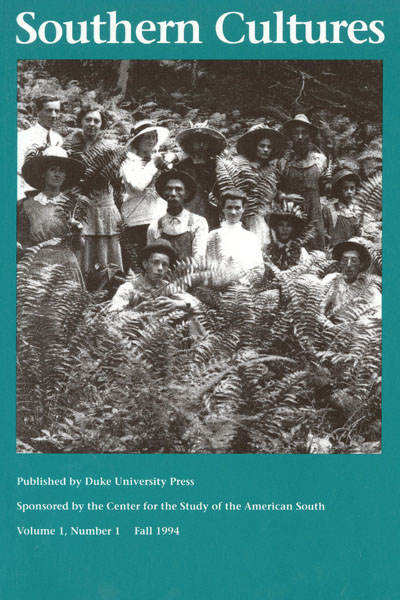

The camera work of T. R. Phelps has been hiding in plain view all over Washington and Russell Counties, in the westernmost tip of Virginia, for most of this century. Phelps’s photographs of life there during the first four decades of the twentieth century hang on walls, fill pages of family albums, and show up in estate sales after the deaths of their subjects or their subjects’ children. These hundreds of images are fragments of the lifework of a remarkable photographer.

Yet Phelps himself is still almost as little noted as the estate-sale photo albums and prints of his work; before 1975 he was almost unknown. That year, his grandson, Gale Phelps, contributed a photographic essay from the collection to the August issue of the Plow, a small literary magazine. Since then, he and photographer friend Dean Barr have mounted exhibits for local festivals. In 1992, Gale Phelps deposited the family’s archive of nearly two thousand plate-glass negatives at Emory & Henry College, a few miles south of the Phelps homeplace, and, in 1993, the school staged a major exhibit, “The Phelps Collection: A Photographic Treasure of Washington County.”

The collection is valuable not only because of its size but also because it starts earlier and runs longer than most collections of mountain images. To have such a collection of images taken by a local resident to juxtapose against collections of outsiders’ photographs is remarkable. To have such a collection for Appalachia is rarer still. There is more to these images than rarity, however. Phelps was technically and artistically talented, not only indigenous, and humorous as well as deft in his recording of the people, rituals, ambitions, and changes in his world.

A Hidden Trove of History

Born 24 November 1872 in northern Washington County, Thomas Rupert (T. R. or Tommy) Phelps lived all his life in Moccasin Gap, near the north fork of the Holston River. Because he suffered from “milk leg” (or “white swelling”) and from a kneecap shattered in a sledding accident when he was a young man, he could not farm as extensively as his parents or six siblings. Instead, he ran a grist mill and repaired watches. After ordering a camera and darkroom equipment about 1897 (perhaps from Sears), he also became a photographer.

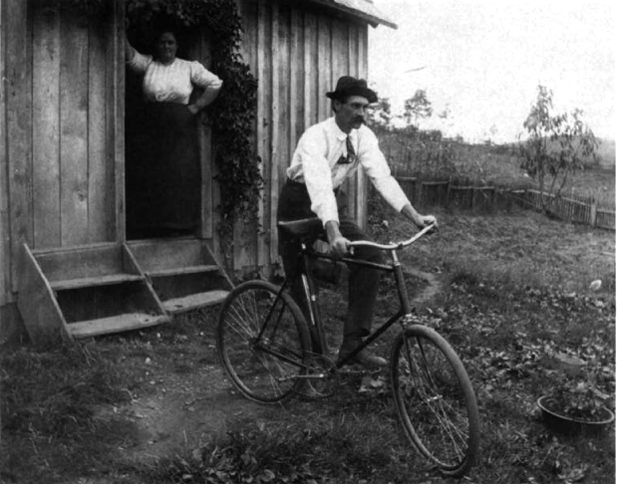

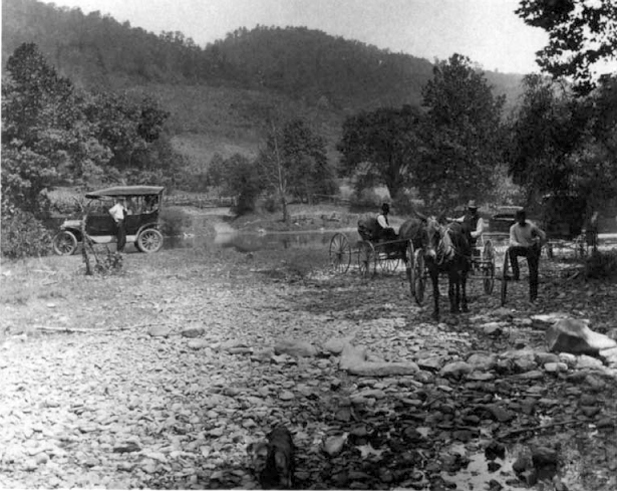

Phelps would set out on Mondays from his homeplace and spend several days driving his buggy over a circuit that took him every three weeks to Bristol and through Washington and Russell Counties. Stopping at farms along the way, he would unhitch his stallion for it to service mares while he repaired watches and shot photos. He never gave up his buggy, even though cars had nearly replaced horses by the end of his career.

After ordering a camera and darkroom equipment about 1897 (perhaps from Sears), he also became a photographer.

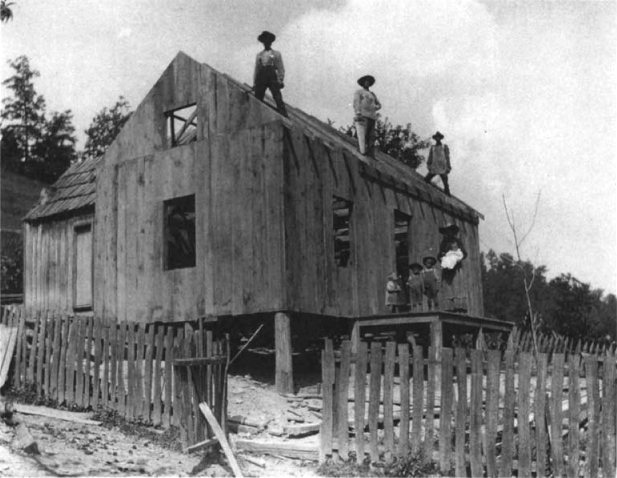

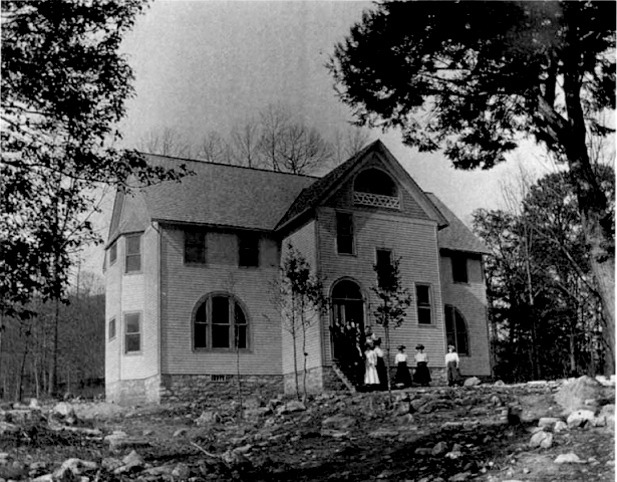

Phelps took an average of five images on each job, using ten of the twelve glass plates in a box on two commissions, so leaving two for “free” shots of lumber gangs, harvesters at work, or staged, sometimes comical photographs. Most of the commissioned images are of couples, children, families, large family gatherings, and school or church groups. Some are of individuals, sometimes with a favorite horse, mule, dog, ox team, or new automobile.

Through recording his neighbors over nearly half a century of dramatic changes in photography, Phelps let advances in photographic technology pass him by. Early in his career, he experimented with roll film but was not successful with it in the darkroom. Thereafter, he continued to use dry plates and a three-by-five camera on a tripod. In his home, he also had a large studio camera. He did not take flash shots, even though flashes were used in a limited way early in his career and made it possible for photographers to shoot nearly anywhere by the 1930s. Even earlier, around 1920, halfway through his career, most commercial photographers had switched to roll or sheet film, but Phelps continued to use glass-plate negatives. And he did not put away his tripod later in the decade, when the introduction of small, handheld cameras like the Leica allowed journalists to take candid shots that he could not.

One should be grateful that Phelps did not make the switch from glass plates to film.

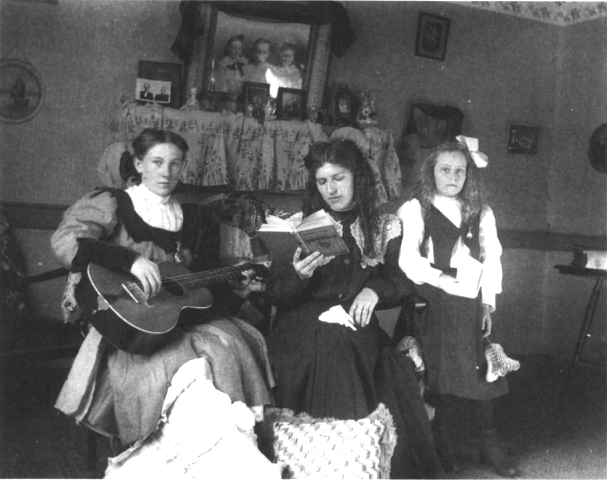

Phelps’s reluctance to use new techniques constrained his work. Because he did not have a flash, he took only a few interior shots, though these show a fine use of natural light. And since his equipment did not allow him to take candids, all of his images are posed, even in the midst of a rat kill or swim. All one has to do is to study the expressions of the children to see how serious—and sometimes painful, sometimes hilarious—posing was.

In a way, however, one should be grateful that Phelps did not make the switch from glass plates to film. The glass negatives, though fragile, have survived much better than the combustible roll or sheet film would have. Many nitrate film archives have gone up in smoke in the years that Phelps’s collection lived under a bed at the Phelps farm.

An Insider’s Perspective

Even though Phelps continued shooting until his first stroke in 1939, his work belongs to the era from the 1880s through the 1920s, when the professional photographer brought the camera home to much of America—the same era that saw the dramatic development of the department store, the automobile, and the manufacturing assembly line. Indeed, Phelps might not have become a photographer if advances in photography and merchandising had not made it possible for him to order equipment from a department store catalog. He also would not have been able to make part of his living at photography if the demand for photographs had not spread as far as it had among his neighbors or if there had been many more amateur camera owners in his area.

The extent to which being local helped or hindered Phelps in other ways is not clear. He did not have the market entirely to himself; there were commercial studios in the bigger towns to which Washington and Russell County citizens sometimes traveled. Phelps may have found it easier to come to his clients’ homes and churches than did these town-based commercial photographers. On the other hand, one may also suppose that he did not have the same professional image or aura as a studio photographer.

That Phelps was an insider, a birthright member of his community, may have colored not only his subjects’ views of him but also his treatments of them.

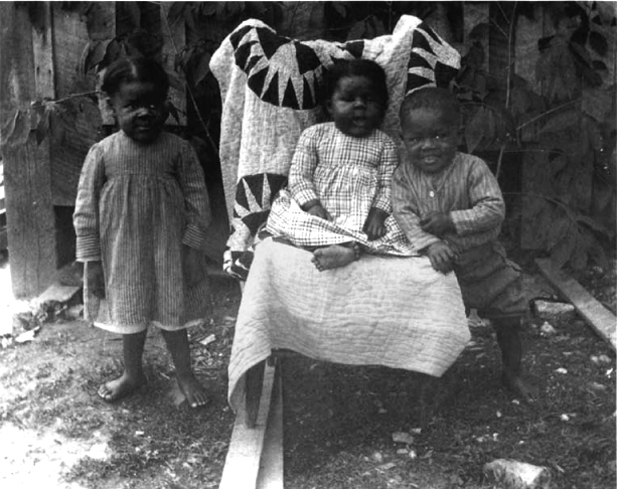

That Phelps was an insider, a birthright member of his community, may have colored not only his subjects’ views of him but also his treatments of them. Consequently, his images hold a kind of interest and value that a stranger’s cannot. Individual Phelps photos might not be obviously distinguishable from those by his contemporaries who ventured into the mountains from outside the Appalachian region, but his relationships with his subjects were different. For example, cosmopolitan urbanite Doris Ulmann, who ranged through the mountains by limousine during the decade before her death in 1934, was intent on recording the distance of the Appalachians from metropolitan life. She even got young women to wear their grandmothers’ dresses and otherwise manipulated her subjects. She thus captured elements of a past otherwise beyond reach and at the same time brought attention to the strangeness and beauty of the day-to-day lives, implements, and habits of “backward” or remote peoples. Implicit in her images is the sophisticated city dweller’s appreciation of the “quaintness” of the country and the social reformer’s sense of the pressures of poverty as well as the pride and resilience of the poor.

Phelps photographed with different intentions. Ulmann once complained that her subjects all wanted “to go and dress up,” then added, “It is not an easy task to induce a farmer’s wife to have her picture taken in her kitchen peeling potatoes”—especially in her grandmother’s dress. Phelps did not have those difficulties. He was commissioned by friends and neighbors to record the ritual high points of their lives—christenings, marriages, family and church picnics—as well as loved ones in their Sunday best.

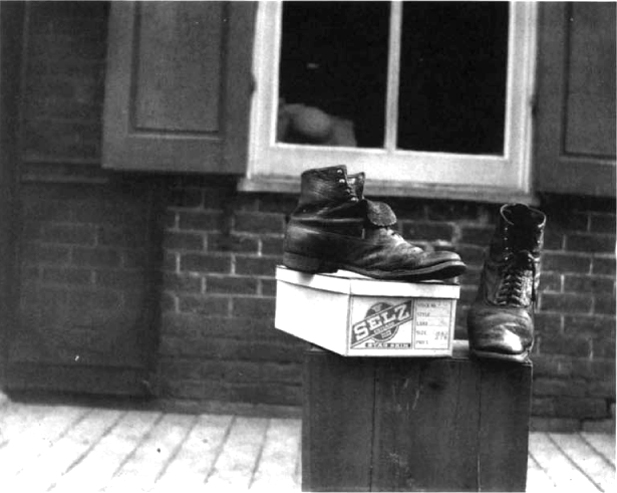

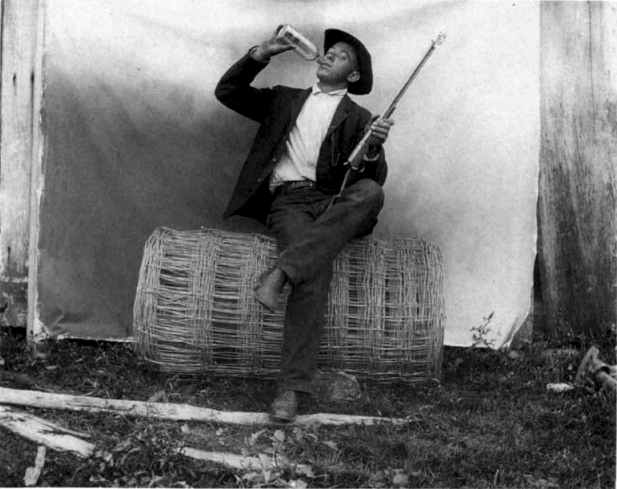

Often, too, Phelps and his subjects seem to have amused themselves by staging scenes that poked fun at the stereotypes held by the city tourist, the ethnographer, and the social reformer or the Puritan. A still life of worn shoes is one example. A portrait of a young man with a liquor bottle and a gun with a flower coming out of the barrel is another. In capturing his subjects, then, Phelps, in a carnivalesque mood, sometimes subverted conventions that Ulmann used. At other times, especially for formal portraits, he carefully observed those conventions that she worked hard to avoid.

Of course, Phelps did not limit himself to his commissions. Many of his shots show his family, friends, and neighbors at work and play, weaving, logging, plowing, harvesting, swimming, or fishing. Sometimes these are intimate, individual portraits; sometimes they are panoramic views or group portraits. He also made portraits of houses, mules, and dogs. But even though these pictures are obviously staged, Phelps did not manipulate his subjects the way Ulmann frequently did.

Phelps’s photos are often superbly composed. They have balance, movement, texture, and clarity. In many cases, the compositional virtuosity goes farther to include fine detail, such as the interplay of the small angles between a hat and a gun or the stances of children and animals. What is not clear from the negatives and must await the gathering of as many of Phelps’s old prints as possible is what Phelps may have done in the darkroom to alter, enhance, or accentuate elements of particular images.

The Future of the Phelps Collection

In his own time Phelps was little known outside his local area, [but] his obscurity was not inevitable. Historians have written about Erwin Evans Smith, the “Cowboy Photographer” of Texas and New Mexico, Phelps’s junior by fourteen years. Collectors have sought examples of the work of Frank M. Sutcliffe, the “pictorial Boswell of Whitby,” the Yorkshire, England coastal town where Sutcliffe spent most of his life, until his death in 1941, quietly photographing his world and its inhabitants as naturally and realistically as he could. The art world has long been drawn also to the Appalachia seen through the artful lens of Doris Ulmann. Social reformers and the publics they reached have been moved as well by the photographs of children in mines and fields by Lewis Wickes Hine, Phelps’s almost exact contemporary, and by such younger, Depression-era photographers for the federal Farm Security Administration as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. New books look at the work of yet other Phelps contemporaries among southern commercial photographers, the Bürgert brothers of Tampa, Florida, and Jonathan Trlica of Granger, Texas.

That Phelps’s obscurity is understandable, however, does not mean that it is deserved. The Phelps collection holds great promise for the recovery and appreciation of life in the pre-World War II highlands of southwestern Virginia and northeastern Tennessee. To realize this promise will require intensive and extensive analysis by a variety of locally informed and academically trained readers of photographs. Already Barbara-lyn Morris at Emory & Henry College is soliciting help from locals in identifying subjects of the Phelps photos.

The potential of the Phelps archive remains largely untapped.

To read intelligently, the unaided eye is not enough. Even unaided, however, the eye can tell that Phelps’s work rewards one’s attention at different levels. The potential of the Phelps archive remains largely untapped. Local and family historians should be vying with historians of photography, cultural geographers and historians, industrial and agricultural historians, novelists, poets, and documentary filmmakers to study the collection. In time, too, these images should begin to appear in more publications than in the past.

David Moltke-Hansen is an independent scholar and editor for the Cambridge Studies on the American South. He was director of the Southern Historical and Folklife Collections and curator of manuscripts at the library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill between 1989 and 1999 and a research associate for the Center for the Study of the American South between 2008 and 2011.NOTES

The author would like to thank Barbara-lyn Morris, Gale Phelps and his family, Dean Barr, Jerry Corten, Alex Harris, John Morgan, Jack Roper, Wendy Strain, Clara McHorris, and Kelly Espy for the information and advice they provided.