Don’t you wonder sometimes

’Bout sound and vision?

Blue, blue, electric blue

That’s the color of my room

Where I will live

Blue, blue

Pale blinds drawn all day

Nothing to do, nothing to say

Blue, blue

I will sit right down, waiting for the gift of sound and vision

And I will sing, waiting for the gift of sound and vision

Drifting into my solitude, over my head

Don’t you wonder sometimes

’Bout sound and vision?

—David Bowie

Recently, I joked with Tom Rankin—guest editor of the Spring 2020 Documentary Moment Issue—that lately I don’t read anymore, I just look at art. When I first admitted this, sheepishly, I was embarrassed. But the past few weeks have confirmed the merits found in observing, examining, gazing. Especially when we collectively find ourselves turning inward and sheltering in spaces of our own making, art becomes a source of comfort. Looking at art creates room to think and to imagine how we might contribute to the fabric of history. Art invites us to approach it on our own terms.

Even as many of us are homebound, we can find creative ways to engage with art in all of its forms, and wonderfully, there is something for everyone. Galleries are setting up online viewing rooms, museums are opening digitized collections to the public, families are relying on art supplies to occupy a nation of children. We can find inspiration in a book, in nature, at the soft tip of a brush, or in the smears of our children’s finger paintings that seem to us masterpieces. Armed with art, we find a way to navigate uncertainty and dream new futures, based not on fear but on connection.

Like all of us, I find myself and my family caught in the ever-changing landscape of a global pandemic that threatens the lives and security of not just one family, one town, one city, one region, or even one country. The very fabric of the world as we know it is being rewoven, tested for strength, any small gaps rapidly patched or, devastatingly, ripped open even further. Depending on where you sit, the virus’s effects are akin to being pricked by a pin or hit by a boulder. Personally, I have been preoccupied with how to get through the day sequestered at home with two small children, a partner who, like me, has work to do, and a dog who wants to be walked. It can be comforting to know that we are all gathering information, scanning the landscape for signs, and remaking our lives to handle what might come next.

Our changed world provides a new momentum for this issue: creativity as a saving force, that energy from which innovative ideas are born, that spirit that makes it possible to thrive in our present circumstances and bring a new future into being. Art, southern or otherwise, is a pathway to connection within ourselves and with others. In this new reality, art is as essential for survival as it ever was.

In this new reality, art is as essential for survival as it ever was.

In my job as a curator, my days are mostly filled with looking at art. I am drawn to work that welcomes the curious and implies rather than dictates. This issue, our first ever dedicated to visual arts in the South, is an invitation to see what some of the diverse artistic voices connected to the region are up to. Great art prompts rather than directs conversation. That doesn’t mean that the work doesn’t have something to say—indeed, sometimes it yells above the din to get our attention or whispers in the quiet to draw us in. Other times, it whispers when it’s loud so it’s almost impossible to hear, or yells when it’s quiet and turns everybody off. But that can be compelling, too, and requires us to work a little harder to make sense of it all. We might just be entering one of those times when some extra effort is necessary.

The artists and thinkers in this issue are all asking us to make an effort to engage art not just for what it represents but also for its possibilities. The work and words in this issue can be considered a pastiche, a series of conversations between people and around ideas that may not at first appear to be related but in the end are all part of the southern constellation. Seen together, new heavenly bodies emerge. In particular, the work in this issue explodes the notion of the South as a purely dichromatic space, black and white. How many voices have been ignored and truths forgotten at the service of that too-convenient, insidious dichotomy? In their contributions, Michelle Lanier and Monique Michelle Verdin each consider how conventional mapping glazes over so much of the rhizomatic and perpetually unfolding nature of history, and the roles we play within it. Allison Janae Hamilton’s eloquent photography is invested in the beating heart of the land itself, where landscape is not a background but an equal partner and principal character within a mythological South.

Christina Snyder’s writing on Indigenous moundbuilders in the Southeast prompts us to remember that how we write history and remember rituals depends on who is doing the telling. Jessica Ingram’s photo essay explores how landscapes are marked with our collective memories; even the most seemingly mundane spaces have born witness to unspeakable things.

Photographs by Susan Harbage Page and the late Diego Camposeco, thoughtfully considered by Deborah Willis and Jeff Whetstone, respectively, demonstrate in their own ways the nature of privilege and power. Likewise, artists Deborah Roberts and Amy Sherald share southern roots that have influenced their practices to varying degrees, particularly in how they grapple with visibility, representation, and power. Tommy Kha’s “kissing pictures,” introduced by Courtney Yoshimura, cast viewers as possible voyeurs who are asked to ponder intimacy, consent, and agency with the artist’s own body as a reluctant site of desire.

In retrospective fashion, Mel Chin delves into the archive of his own work over the past thirty years to recall the sources of his artistic inspiration, how what is old is always new, and how art provides an opportunity for beautiful, fantastical envisioning and creative problem-solving. Jessica Lynne invites readers on a journey of intimate buried histories that, once unearthed, help us to better know ourselves.

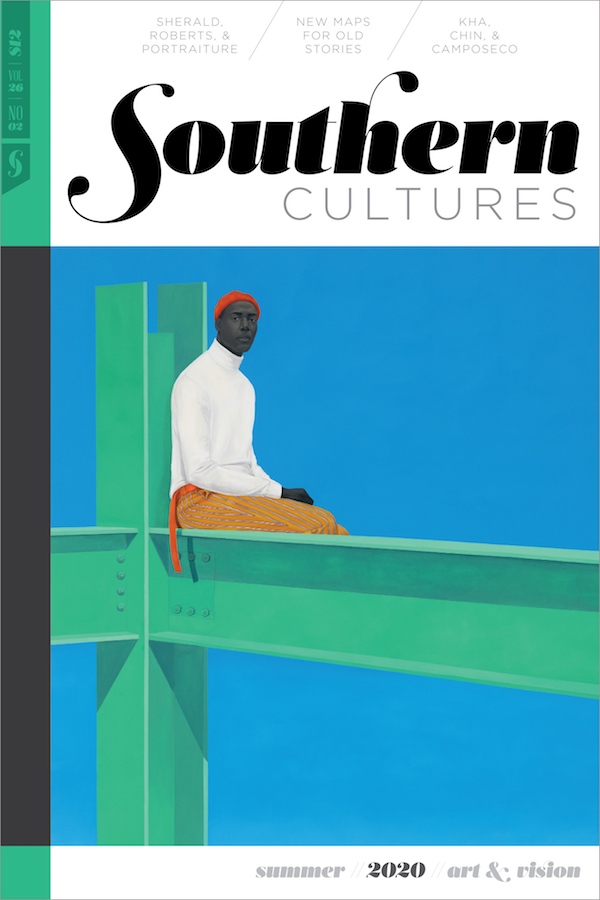

In its title, Art and Vision, this issue takes its cue in part from David Bowie’s song “Sound and Vision,” the first single and perhaps most readily recognizable and straightforward track from his 1977 album Low. For non-Bowie fanatics, I won’t bore you with the minutiae around this landmark record in his Berlin Trilogy—that is for another essay. But relevant to this conversation is that Bowie wrote “Sound and Vision” about the muse, the elusive nature of inspiration—something he was intimately acquainted with as an artist and musician. It is a song about finding creativity through isolation, possibilities that arise when we retreat. “Blue, blue, electric blue”—the color of inspiration, certainty, stability, faith. Anyone who has taken Art History 101 recalls that in countless pietàs, the color of the Virgin Mary’s mantle is blue—the color of believing in the face of despair, believing in the impossible. It feels prescient that this song was inspiring the ideas behind this issue, completed in a space of voluntary self-isolation, where we are invited to retreat not just for our own well-being but for that of a greater community.

Surely Bowie, at times a fervent believer and at others a skeptical theologist, was aware of the blue room’s double meaning—a space of both possibility and despair. Bowie crafted his lyrics with care, leaving his audience to wonder about the very nature of inspiration and what it requires. In search of the muse and to create his own luck, Bowie often used the “cut-up method” to write song lyrics, essentially pulling phrases from literature, current events, and his own imagination, then cutting them up and putting them back together again. In this method, the law of surprise—that which you possess but do not yet know—decides what is art. Revelations surface by surrendering to chance. Vision requires relinquishing control enough to find coherence in chaos, allowing what dreams may come and believing in them.

Vision requires relinquishing control enough to find coherence in chaos, allowing what dreams may come and believing in them.

In a 1970s interview, Bowie described the cut-up as “a very Western tarot,” which might describe art as well. Though Bowie learned of the approach through reading William S. Burroughs, who popularized the method in the 1960s, the cut-up technique has a much longer history, employed by Dadaists in WWI–era Zurich in their efforts to highlight the nonsensical horror and frivolity of war (they called it découpé). Whether through words (découpé) or images (collage), unexpected juxtapositions offer the prospect of new vision and understanding.

In Art and Vision, I am interested in unexpected juxtapositions as a way of considering not just southern visual culture but also the nature of experience itself. Here, we shall take some of the raw material of regional visual expression—the various tropes, stereotypes, highs, lows, successes, failures, and surprises—cut them up, and put them back together again. In so doing, we might just draw a new map of many disparate stars that, taken together, form a complex and shifting tableau, impossible to define, that tells stories not always visible but present nonetheless.

It is the perfect moment to gaze at art, envision what is possible, and engage in meaningful discourse. If we can honor those perspectives that might not always be in sight but are ever-present, we might finally find our way toward a collective peace. But more realistic in the short term is the simple potential of this moment to wake the muse. Art can bring people together in the darkest times, providing a vital creative outlet and space of hope. By being still long enough to look, to read, to think, we might find the inspiration to reconsider the past and sit with the present in service of a new future. In this strange and difficult moment, what can be imagined? What are we driven to seek when reality is uncomfortable? How can the gift of art lead us to picture what we dream, and make it so?

To wit, dear reader, consider this issue as a humble cut-up or a call to arms, a light in the dark as we’re waiting for the gift of art and vision.

This essay opens the Art & Vision Issue (vol. 26, no. 2: Summer 2020).

Teka Selman is an independent cultural advisor who has been in the contemporary art world for over twenty years, collaborating with artists, collectors, and institutions as a curator, writer, and consultant. After honing her skills in Chicago, London, and New York, she relocated to North Carolina, drawn by the burgeoning art scene of the Southeast. She is cocurator—with Lauren Haynes—of the inaugural Tennessee Triennial, slated to open in venues across Nashville, Knoxville, and Memphis in 2021. Teka lives in Durham, North Carolina, with her husband and two daughters.