“‘That’s all I wants to do . . . to find something to can. I can stay in the kitchen from morning ’til night canning—’if I can find something to can, and have the jars, and the tops—’good tops, and lids. I loves to can.'”

In a 2008 ethnographic celebration of American county fairs, Drake Hokanson and Carol Kratz pointed to pigs, quilts, and dirty pickup trucks as surefire signs of rural culture. Jars of colorful award-winning preserves also affirmed the vibrant life beyond urban centers: after all, the authors asked, “Who in the city makes jelly?” Indeed, jars of sweet potato butter, corncob jelly, pickled ramps, and peach-pecan preserves proclaim country pride in venues across the South today. They crowd the shelves of the Museum of Appalachia store in Clinton, Tennessee, and balance in stacks at the Western North Carolina Farmers’ Market in Asheville. Farther east, in South Carolina’s Lowcountry, the Charleston Farmers’ Market offers downtown visitors half-pints of muscadine-apple jam from Grace’s Kitchen, and a repurposed gas station off the Charleston Highway stocks condiments like sweet tea jelly (from Rina’s Kitchen) alongside local barbecue sauces and plates of fresh pie.1

After all, the authors asked, “Who in the city makes jelly?”

Yet county fairs and regional gift shops hardly have a monopoly on home canning displays: preserving food in city dwellings and urban apartments has become hip in the twenty-first century. Liana Krissoff’s Canning for a New Generation: Bold, Fresh Flavors for the Modern Pantry (2010) is just one of many recent publications oriented toward novice canners and new canning contexts. The book’s roots lie in Krissoff’s memories of her parents as they worked to contain the surpluses of their Virginia and Georgia gardens, but it caters to those who associate pickles with curried lentils and sashimi, who would bypass standard peach jam in favor of “a small spoonful of fig preserves with port and rosemary alongside a wedge of veiny blue cheese and a thick slice of dark bread.” Krissoff unapologetically promotes the pleasures of home preserving, not least because of its social benefits: a jar of marmalade received in the mail can materialize an otherwise-virtual relationship with a fellow food blogger, making the connection as tangible as the blueberries spread on her morning toast. Upbeat, intimate, practical, and epicurean, Canning for a New Generation advocates a sensual revival characterized by playful creation and exchange.2

The same year that Krissoff published her cookbook, Slate columnist Sara Dickerman wrote that preserving at home had become “ridiculously trendy,” its products mere “culinary trophies” meant to display an “overwrought” and morally framed gourmand aesthetic. In the second decade of the millennium, she lamented, canning had shifted from a modest, frugal, and routine practice into one overlaid with a “revivalist fervor” that centered on the “thriftiness, healthfulness, and environmental virtues of marmalades and dilly beans.” Dickerman doubted that the production of small-scale fancy condiments constituted a meaningful political statement, that project-based preserving could effect significant environmental or economic regeneration, or, she implied, make a dent in larger American problems such as hunger or an abusive industrial food system. But on another level, her displeasure hung on the social and sensory aspects of new-generation efforts, which she characterized as expensive “fits of showy industriousness,” their products “bloggable and boastworthy” but ultimately frivolous. In this view, rosemary-infused fig preserves are out of step with historical practice, which focused on “serious” food like unadorned stewed tomatoes or salted green beans—the kind of goods “on which you could actually base your diet.” “As with many food trends,” she concluded, “today’s cultish hobby was yesterday’s necessity.”3

Dickerman’s is not the only public voice that emphasizes creativity and choice in canning’s (urban) present, but compulsion and need in its (rural) past. In 2006, the editors of an oral history project in rural Kentucky observed, “These days, some may choose to can and freeze certain products, but in the past, it was a necessity.” One 2012 blog post characterized today’s “popular hobby” as an enjoyable mode of voluntary frugality—as distinguished from the activities of home canners during the first and second world wars, who dealt with produce that “had to be preserved” as a matter of “life or death.” In 2013, journalist Emily Matchar wrote that home canning, “once the dying art of rural grannies, has gone viral as foodies have come to see home preserving as a way to control the food they eat.” And a 2014 article in the Bitter Southerner implied the existence of a substantive divide within present-day home canning. Chuck Reece profiled Atlanta’s Preserving Place—a west side storefront, production facility, and diy canning education center established by former lawyer Martha McMillin as a way to promote ethical, thoughtful foodways. The article acknowledged common ground between Preserving Place’s urban clients and the patrons of Georgia’s many rural community canneries, noting that those who prepare food in either site are often motivated by past practice. But like many recent articles, Reece’s skipped past engagement with actual rural voices. Instead, the piece emphasized that people in the city might want to can “because it’s cool” or in order to reconnect with tradition, while assuming that rural canners preserve food “out of necessity,” either as an inherited habit (something simply “in their family tradition”) or because “they can’t afford not to.”4

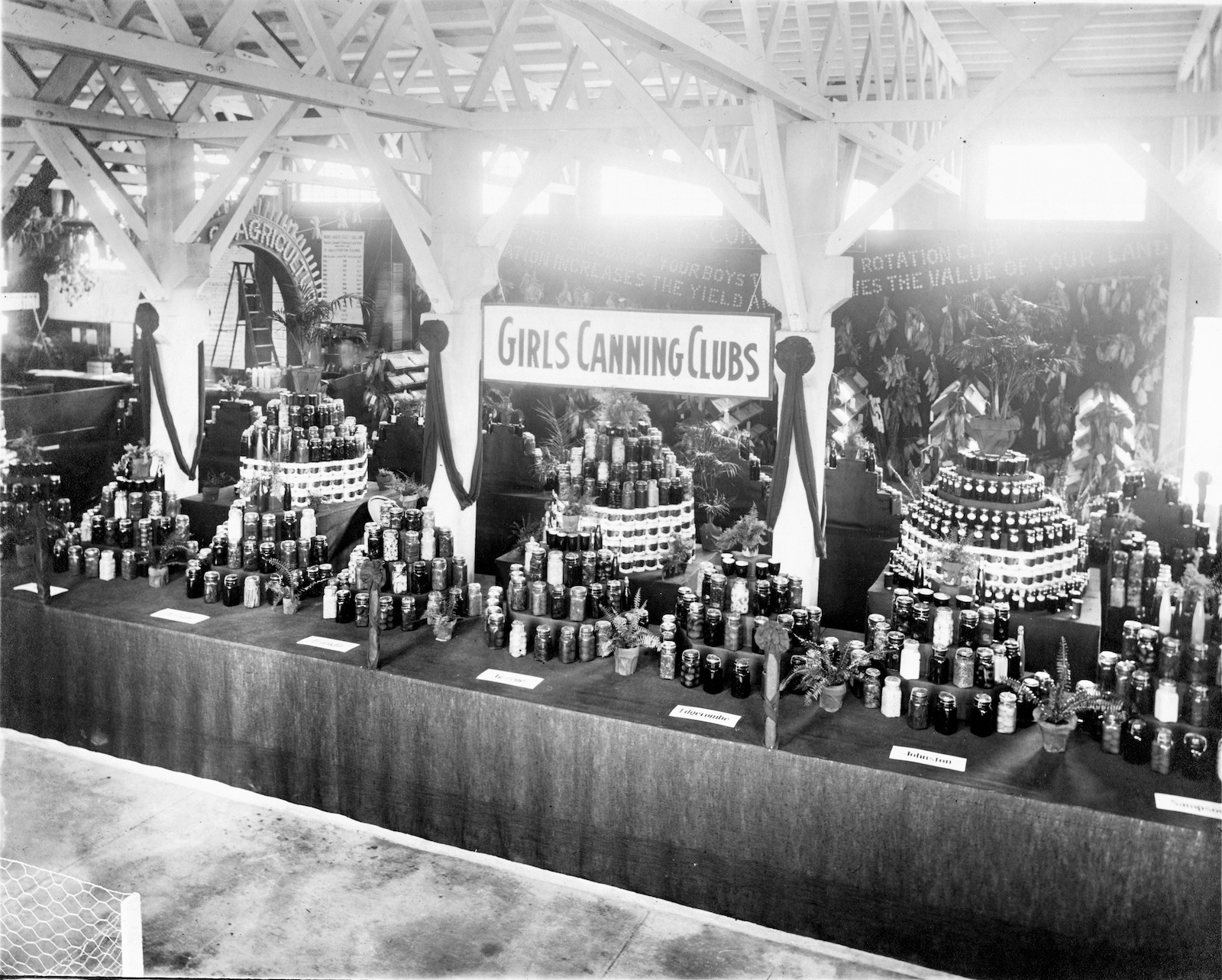

In fact, home bottling in the rural South has never been purely about necessity; carefully arranged displays at agricultural fairs over the past two centuries should be enough to dispel the notion of a strictly utilitarian folk unconcerned with options or artistry. Moreover, working-class women across the South have consciously called attention to the social and aesthetic pleasures of preserving. In recent summers, as enthusiasm for revivalist canning continued to grow, I found myself paging through self-published cookbooks, browsing archived photographs, and listening to conversations recorded in the last decades of the twentieth century. In these records, evidence of southern poverty and struggle surface in abundance, clearly indicating that the men and women documented by fieldworkers and family members preserved much of their own food because it kept hunger at bay or bolstered home economies pieced together from multiple resource streams. I do not intend to romanticize the hardships that have accompanied home food production: during the 1930s, one sharecropper’s wife described late summer canning as “a woman’s hardest time,” hot work piled onto everyday tasks and wedged between tending the garden and harvesting cotton. And as a recent North Carolina State University study observes, cooking from scratch continues to be unequally gendered labor that can cause mental and physical distress, especially when women must juggle food preparation with unpredictable work schedules, uncertain transportation, tight budgets, and the demands of their various eating audiences. Still, archival work suggests that reducing past rural domestic practice to duty or deprivation alone ignores the agency and aesthetic sophistication of people already marginalized by gender, region, race, and other contributors to socioeconomic status. Women from the coal camps of West Virginia to the wetlands of Louisiana have had much to say about need, beauty, display, and exchange as they’ve discussed the production of home-bottled foods.5

Home bottling in the rural South has never been purely about necessity; carefully arranged displays at agricultural fairs over the past two centuries should be enough to dispel the notion of a strictly utilitarian folk unconcerned with options or artistry.

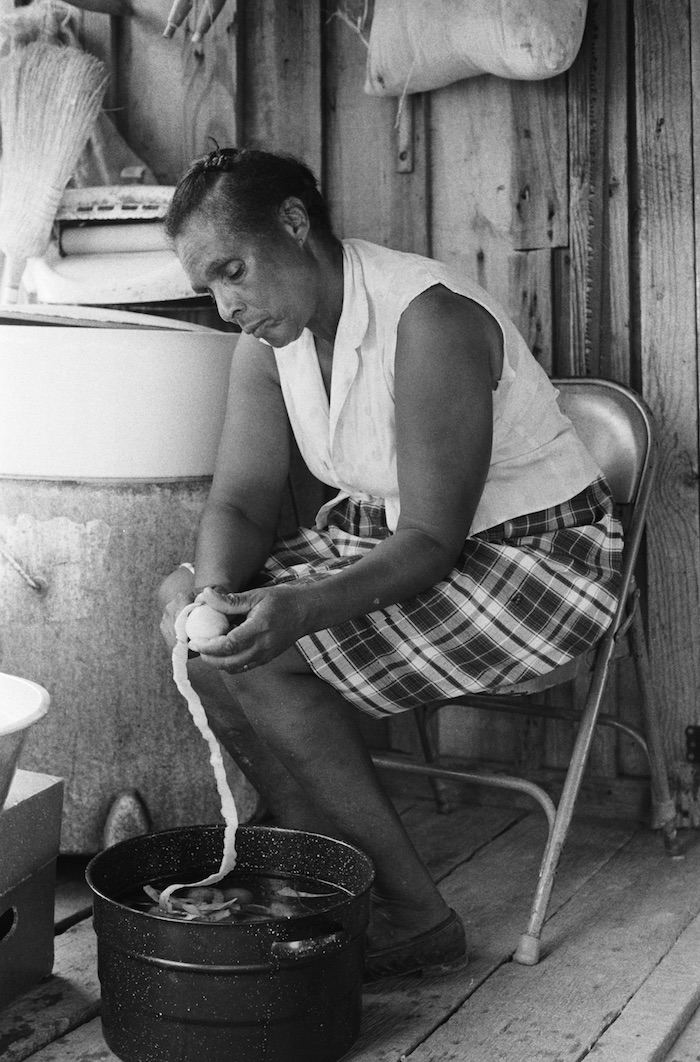

Addie Mae Dotson offers one such voice. In July 1973, staff from Memphis’s Center for Southern Folklore turned onto a dirt road about a mile east of Highway 61 in Lorman, Mississippi, looking to meet Dotson and her husband Louis under the feathery shade of a chinaberry tree. In the Dotsons’ swept dirt yard, chicks peeped from a wooden Coca-Cola crate, and sawhorses made from forked branches offered convenient seats for visiting children. A series of troughs and gutters wired to the corrugated tin roof of the couple’s home channeled rainwater to a barrel cistern, various pails, and an enameled canning kettle; black electrical wires snaked to lightbulbs, a wringer washer, and a small television. Over the course of several days, folklorists William Ferris, Judy Peiser, and Ferris’s sister Hester Magnuson visited with the Dotsons, recording their conversations and activities, gathering life histories as well as reflections on religion, art, and work. Mr. Dotson, who was in his mid-fifties at the time, slopped the hog on camera, took the crew to his fishing spot, and demonstrated how to “talk the bottle” and play the one-stringed guitar he’d installed on the side of his house. Ferris and Peiser later produced a short documentary that gives a glimpse of Mrs. Dotson’s skills with a bottle as well: after chopping weeds from the collards in her sun-drenched garden during the film’s opening frames, she peels dozens of small peaches into a kettle of water, then slices the recalcitrant fruit’s flesh from clinging stones so that she can seal it in jars.6

Many of the images produced during that 1973 trip show Addie Mae Dotson standing at a wood-burning cookstove in the front yard, stirring a white enamel basin of peaches and sugar. Sometime after 1968, when fieldworkers first visited, the wood stove had been moved from the kitchen to the front yard; Dotson kept the older technology as part of an outside kitchen that was cooler and saved gas for her new range inside. She did not rhapsodize about the peaches, commenting instead that because she was “not sweet-mouthed no how,” she primarily preserved the canned fruit for her husband, who loved sugary things. She herself preferred sour pickles and bottled snap beans and okra, though she didn’t “care too much about a butter bean after you can it up in a jar. But still,” she reflected, “would I be hungry, I would eat it.” Predicting a rough winter while conversing with neighbor Esco Reynolds on her front porch, Dotson observed, “I’m canning up everything I can. That what I don’t like and that what I like, cause I tell you what, you get hungry, you’ll eat something another you don’t want just to fill up.”7

Well, I loves to can. That’s all I wants to do…to find something to can

Knowing these details alone, it would be easy to conclude that Addie Mae Dotson disliked canning, and that she sweated over her firebox solely out of obligation and anxiety. But in these interviews both Dotsons repeatedly affirmed the opposite. Largely because of Mrs. Dotson’s efforts, the family was mostly self-sufficient, buying from the local store just meat, lard, sugar, coffee, meal, feed for the hogs and chickens—and jar lids. “Well, I loves to can,” Dotson explained with a small laugh. “That’s all I wants to do . . . to find something to can. I can stay in the kitchen from morning ’til night canning—if I can find something to can, and have the jars, and the tops—good tops, and lids. I loves to can.” A little at a time, she put up beans, blackberries, figs, jelly. At one point, as she demonstrated how to can peaches, Ferris commented, “Bet they eat good.” “Oh yeah,” Dotson replied. “I love to can all such as this here but come down to me, I’m not a lover of it. I just loves to can.” Confused by the referent for “it,” the interviewer interjected, “Say what?” Mrs. Dotson reaffirmed: she favored sour or salty vegetables. “I got to go a long ways from home fore I walk up to sweets,” she said, though others would certainly like eating the peaches she was stewing. What she relished was the canning itself.8

Quantity as a Measure of Self-Sufficiency

Addie Mae Dotson’s sentiments are surely not shared universally, but it’s not difficult to find them repeated in diverse sources from a range of times and locations across the South. Directly west of Lorman is Keatchie, Louisiana—the birthplace of Julia Pettaway (b. 1880), star of Big Mama’s Old Black Pot Recipes, a book that acknowledges both the labor and the pleasures of canning. In 1987, National Heritage Fellowship nominee Ethel Rayson Dixon published the spiral-bound cookbook in her grandmother’s honor. Pettaway had married at fourteen and raised nine children, eventually by herself; through a combination of sharecropping and selling cattle, butter, milk, and garden vegetables, she accumulated 100 acres and counted among her holdings apple trees, pear trees, and berry bushes. She made furniture and taught her children to read and write, quilt, sew, and cook. Depicted in a headscarf and apron on the cover and throughout the cookbook, Big Mama is always working, shelling crowder peas in one image, hauling a ham hock from the smokehouse in another. Like many families in the region, hers grew beans, tomatoes, squash, eggplant, onions, and other vegetables in the garden and bottled the surplus for winter, though Dixon only includes recipes for pickled okra, chili sauce, chow chow, crisp pickle slices, and green tomato pickles.9

The cookbook—illustrated with line drawings that depict everything from gathering walnuts to picking blackberries to stumping for catfish—pays tribute to the labor involved in these efforts. “Canning day started early in the morning and often lasted until late evening,” notes the introduction to one section. “The vegetables had to be picked, shelled, and washed. Jars had to be cleaned and sterilized and the woodbox filled with adequate firewood for the stove. Sleep came easy after a long day of canning”—and during the late summer and early fall, all this work might need to be repeated the next day. Dixon traces the process in pictures: a woman and girl work at a table over washpans of vegetables; a waterbath canning kettle boils on a cast-iron stove; a woman moves bottles of preserved food from table to pantry shelf. The book’s dedication page recognizes “every wife, mother and daughter who toiled over a hot wood stove ‘making-do’ with whatever sparse staples that were available to provide for their family a tasty, nourishing meal.”10

Craft satisfaction—pride in a materially productive task well done—is one reason for finding enjoyment in such hard work. The Louisiana cookbook observes, for instance, that the physical rigors of canning were matched by sensory proofs of accomplishment: “The melody of lids snapping as jars of the canned goods cooled and sealed was very soothing as we drifted off to sleep.” The badge of self-reliance is another motivating factor. Throughout much of the rural South, productive workmanship has both aesthetic and ethical meaning; even in places where home food production and preservation has declined, self-sufficiency remains highly prized as a marker of versatility and ingenuity, a way to display specialized skill, relevant knowledge, and personal foresight. Perhaps paradoxically, it also demonstrates one’s immersion in local networks, since doing for oneself enables doing for others.11

The physical rigors of canning were matched by sensory proofs of accomplishment.

It is no wonder that provisioning becomes a cultural focus in contexts of economic uncertainty caused by crop troubles, factory and mine closings, deflated wages, and opportunities constrained by racism, sexism, and other social prejudices. Sadie Miller, a resident of West Virginia’s Big Coal River Valley, knew this kind of uncertainty: she noted that there had been times when she and her first husband, who was often sick from work in the coal mines, “didn’t really know where our next meal was coming from. But it always come.” A generation earlier, Rovertie Bolen Wills had also grown to maturity in West Virginia’s coal camps; during the 1920s and 1930s, without much cash in circulation, her large natal family depended on fresh and preserved produce from their larger-than-average garden.12

When both women were interviewed—Miller in 1995, Wills in 1979—their financial situations had stabilized; however, the urge to make good use of available resources had been engrained through precedent and practice. Miller told folklorist Mary Hufford that she served something she’d canned or frozen herself at the table nearly every day, reporting with a smile that her husband Howard refused to plant anything but tomatoes that year. He had explained, “Well, if I’da planted a garden, you’da worked yourself to death trying to put it all up.” “I love to can,” Mrs. Miller volunteered after relating his comment. “I dearly love to do it. I said, ‘I like in the winter time to see all that good stuff,’ you know—and know that you’re not gonna starve through the winter!” She laughed while relating the incident, proud of a planned self-sufficiency that made the contemplation of hunger amusing. For her part, Wills noted that she preferred the quick, high-yield canning she’d done using metal cans at a community canning center—yet she also detailed at great length her aesthetic preferences concerning the preparation and display of food jarred in glass. It was her simultaneous appreciation of the practical and the beautiful—and her predilection for practices that combined the two, even at the expense of practicality alone—that prompted me to look more carefully for similar articulations in other times and places.

Howard refused to plant anything but tomatoes that year. He had explained, ‘Well, if I’da planted a garden, you’da worked yourself to death trying to put it all up.’

In terms of obviously practical benefit, yield is certainly valued in many accounts of home canning: Farm Security Administration photographers were obviously impressed by amassed quantities, producing albums bursting with black-and-white images of fully stocked New Deal larders. And in her research on cellar houses in Ritchie County, West Virginia, between 1998 and 2005, folklorist Katherine Roberts found that her consultants emphasized quantity when describing canning, referring to huge vessels, long processing times, multiple batches, brimming jars. Most canners also keep a mental tally of just how much they’ve put up. Carrie Severt, in her late sixties when fieldworker Geraldine Johnson visited her Blue Ridge farm in September 1978, admitted that she’d rather quilt than eat, but she filled her cellar with tomatoes, carrots, beef stock, peas, mustard pickles, grape juice, beets, pickles and relishes, sauerkraut, and the like. A single year might see the addition of 80 quarts of beans, 60 quarts of peaches, and 70 pints of homemade fried and packed sausage or cracklings. Canning in quantity—even when Severt had only herself and her husband to feed—was a hedge against crop failure: “I think of that more than anything else, nearly,” she explained. The previous summer “we never hardly made a mess of beans. And this time we just had worlds of em,” she said. “And that’s the reason that I canned so many beans this time. And if I don’t have none [in the garden] next year I’ll still have my canned beans.”13

While “having enough” brings peace of mind, quantity is not the only issue: variety demonstrates imagination during production and permits greater choice at the table. In Kentucky, for instance, Florene Smith noted that gallons of pickled beans and pickled corn offered her family “a bit of a change from canned beans and dried beans.” Lesa Postell, who grew up in Jackson County, North Carolina, and works as a heritage consultant for the Blue Ridge Parkway, printed recipes for an astonishing array of home-bottled food in a 1999 cookbook that documents her family’s foodways in the Smoky Mountains (in part because she feared the loss of this knowledge and these options). Her processing timetables offer a range of methods for canning apples and quinces, applesauce, blackberries, blueberries, elderberries, gooseberries, cherries, grapes, peaches, pears, plums, rhubarb, strawberries, fruit juices, jellies, green beans, beets, broccoli, cabbage, carrots, creamed corn, whole kernel corn, corn on the cob, greens (spinach, kale, mustard, turnip, poke, and dandelion), hominy, okra, peas (including blackeye and field peas), new white potatoes, sweet potatoes, pumpkin, sauerkraut, tomatoes, lamb, beef, veal, pork, bear, venison, groundhog, pork sausage, poultry, chicken, duck, turkey, rabbit, squirrel, trout, and smoked trout. Moreover, her brined and vinegar-based pickle repertoire is impressive, including pickled Jerusalem artichokes, ramps, squash, crab apples, fox grapes, peaches, and watermelon rind among other more common fare. Chapter two, titled “The Canhouse,” bears the instructive subtitle, “It Gives Me Great Pride to See What I ‘Put Up’ With My Own Two Hands.”14

Even if the potential bounty indexed by Postell’s cookbook troubles the idea of poor southerners scraping crumbs from bare cupboards, the real anxieties about hunger and economic uncertainty expressed by Dotson, Miller, Severt, and others still might suggest that rural canning should be interpreted primarily in terms of distress or deprivation. But Margaret Severt Jarvis, Carrie’s daughter, clearly questioned the notion that socio-economic forces beyond canners’ control have compelled home canning outside of elite circles. Born in 1942, Jarvis was in her mid-thirties when she was interviewed in 1978. Her life was hardly one of leisure: she had worked at the Hanes clothing factory in nearby Sparta, North Carolina, for eleven years, until her son was born in 1971. Even while she was taking shifts, she canned—often setting alarms at night to wake her when a batch of bottles was ready to be removed from the waterbath. But when interviewer Geraldine Johnson raised the issue of rural poverty, suggesting that “factories don’t pay enough, people have to can to make ends meet,” Jarvis also stressed the personal and social satisfactions of crafting her stock of goods. She acknowledged that canning did have basic practical benefits, but quickly turned to pleasure. “If I have time,” she said, “I like to can. [ . . . ] And I enjoy it. I like to put it up, and then if I don’t use it, divide with somebody else, you know.”15

Asked how long her cellar in Ennice, North Carolina, would keep her and her husband fed, Severt erupted in laughter: “Lord have mercy, honey, it’d last me a lifetime! [laughing] It’ll last me a hundred year old!” But she hated to see resources wasted. “I thought somebody could eat it, maybe, if I don’t, somebody else can, maybe. There’d be somebody that could eat it, I’d think.” In Big Mama’s Old Black Pot, Dixon noted that her Aunt Fanella, the eldest of nine girls and mother of twelve, counted gardening and canning as favorite activities because they meant “she could always reach under the bed” at her Louisiana home—a place cool in summer and warm in winter—“and pull out the ‘makings’ to cook for a crowd.” Eunice, one of Fanella’s younger sisters, also valued being able to offer “plenty of seconds for everyone.”16

Similarly, although Addie Mae Dotson grew food and “put up” at her Mississippi home against times of scarcity, her intent was not to hoard: she said she would open her newly bottled peaches and eat them “day after tomorrow” if her “appetite call[ed] for it.” Rather, Dotson wanted to be prepared to offer tasty, plentiful food to guests. She aimed to offer a surplus; leftovers after a meal meant that “both of us had enough. But if we eat it all up, maybe somebody didn’t have enough.” And though she personally preferred Irish (white) potatoes to sweet potatoes, she always planted some of the latter, just in case: “I don’t know who may come along and want a sweet potato or something or other. I have one to give.” Moreover, by growing her own garden, Dotson was able to offer quality goods to these guests. She could avoid expensive, shoddy produce at the store, instead picking the tenderest greens and the youngest okra herself, leaving the tough bottom leaves for the hogs: “I don’t eat it [old produce] and I’m not gonna give it to nobody and I’m not gonna sell it.” In fact, she didn’t sell anything she grew or made: “Give it. That’s the way it is with me. Cause I look for somebody to give me and you got to share some with somebody so they can share some with you.” Because her siblings were dispersed to New Orleans, Chicago, Jackson, and Fort Worth, her primary partners in these exchanges were neighbors and relatives by marriage.17

I don’t know who may come along and want a sweet potato or something or other.

During a visit with Mary Hufford in 1995, Sadie Miller narrated the personal networks she had fostered in Drews Creek, West Virginia, by exchanging raw materials, recipes, and finished products. She’d just finished demonstrating how to can the beets gifted by a neighbor, and she continued tracing origins and connections as she gave Hufford a guided tour of her cellar shelves. “Them green beans is what that man down the road give me,” she said. “And here’s some pickled cantaloupe—did you ever pickle any [laughing] cantaloupe? I took the recipe out of an Amish cookbook. The cantaloupe don’t taste bad—but the bananas [melon] is terrible!” Another woman had made the apple butter on the shelves—an item they didn’t really need more of, but which Miller wanted to make “for fun,” using a second-hand kettle she’d acquired. She pointed out the relishes she’d inherited from her husband’s first wife, as well as the blackberries that her mother had taught her to pick and can—a store not replenished that year because her favorite patches had become inaccessible due to mired roads surrounding a new coal mine. Like a photo album filled with images of friends and family, Miller’s cellar shelves evoked people, places, relationships, and obligations.18

Like a photo album filled with images of friends and family, Miller’s cellar shelves evoked people, places, relationships, and obligations.

Food gifts (and the social networks they create) thus take many forms, from the ceremonious to the spontaneous. Berta Waldroop “Mama” Matheson, Lesa Postell’s great-grandmother-in-law, created a relish called “Hot Tom” that became beloved by her Nantahala mountain community; she held the recipe close even as she presented jars of the stuff throughout that North Carolina region in the early decades of the twentieth century. When Postell married into the family, Mama Matheson gave her the recipe itself—and “Hot Tom” garnered Postell so many blue ribbons she stopped entering it in contests. In a more casual mode of gifting, her Uncle Frank invariably opened his apple trees to visitors, urging them to pick fruit when they arrived and as they were leaving. Postell paid tribute to his generosity in an epigraph to her chapter on canning fruits: “Friends and strangers they impart / You don’t have to pay; / Take an apple for yourself / To eat along the way.” Other southerners remember barrels and crocks of pickled corn as treats that children could sample at will.19

That’s the talent God give me—to give.

In short, home food production and preservation has long allowed people to contribute quality goods to reciprocity-based economies. Rather than enabling isolation, self-reliant practices like these can help forge social networks as people share diverse talents and goods, permitting more flexibility in tasks and timing for all. Thus, “he’s a hard worker” or “she’s not afraid of work!” are high compliments in Ritchie County, West Virginia, while in rural Kentucky, resourcefulness has been “regarded as the essence of the good person.” This ethic of exchange-enabling labor accompanied mountain migrants to textile factories like Poe Mill in Greenville, South Carolina. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, Mary Thompson’s mother put up produce the family grew in mill village garden plots; while this store helped feed her seven children, she also shared it with her neighbors, and together they pooled supplies that helped tide over families whose head of household had fallen seriously ill. “My mother canned vegetables and things,” Thompson said during an interview in 1979. “Back then, people were very nice to one another, too. If one didn’t have it, they wanted to divide with them, you know.”20 For Addie Mae Dotson in Mississippi, this kind of reciprocity continued to ground her both socially and philosophically: “That’s the talent God give me—to give,” she said in 1978. “And I don’t just say I have a hard way to go through the world, no time. Look like I have an easy way. Look like somebody always, little much, putting something in my hand. And it be the very thing I be wanting, whatever they give me.”21

Canning Aesthetics and Display

In the current canning revival, exchange is an equally important component, though what is being gifted may appear out of step with “traditional” practice. Much of this recent energy focuses on condiments: high-sugar or high-acid small-batch “extras” that foreground creative combinations of ingredients and often serve as the crowning visual and gustatory embellishment of larger meals. Jams, preserves, and pickles, which require minimal time and equipment to process safely, are easily produced in small quantities from a basket of berries obtained at a farmers’ market, or inspired by the abundance of cucumbers that arrive as part of a CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture) subscription. These jams and relishes are also lovely to name and to taste, prompting admiration both in and out of the jar, and they’re often intended as gifts from the outset. Gifting was one aspect of revivalist canning that seemed to bother Dickerman, author of the Slate critique, inasmuch as the practice implies unnecessary excess instead of the frugal management of scarce resources. But the aesthetic aspects of hipster or upscale preserving appeared to trouble her even more: she saw “hedonism” in “heirloom apples and tattoos” and in the “rococo creations” of Liana Krissoff’s new generation.22

It’s worth noting that there has long been a place for the “rococo” in home food preservation. Recipes that require a more elaborate range of ingredients and preparation processes—not dissimilar from the fancy goods created for centuries by European ladies and their confectioners—were often set aside in the “preserving” sections of instructional books printed throughout the last century. For instance, only ten pages of the seventy-five in Sarah Tyson Rorer’s 1887 booklet Canning and Preserving deal with bottling single fruits and vegetables suspended in water or light syrup; the rest provide recipes for things like “tutti-frutti jelly” and “melon mangoes” (the latter referring to a melon that has been hollowed out, stuffed with a concoction of horseradish, cloves, nasturtiums, chopped cabbage, and other items, and then pickled in vinegar). Six years earlier, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking—published at the behest of wealthy California patrons—included several similar recipes that caterer Abby Fisher had presumably prepared while working on plantations in the Deep South. Certainly these kinds of goods have been used to offer pleasure and signal class position within rural communities as well, and we’ve seen that country canners are no strangers to variety, having long been fairly certain that (to borrow the satirical Portlandia tagline) they “could pickle that.”23

Nor are taste and beauty the exclusive concerns of wealthy urbanites. However, in the southern materials I’ve explored, people don’t spend time searching for specific adjectives to define the food they make and prefer. Desired texture is articulated most often and precisely in interviews and cookbooks: pickles should be crisp (ensured by adding alum, lime, or a single washed grape leaf during processing); crusts should not be soggy (and thus rehydrated fruit rather than canned is best for fried handpies); produce should be fresh and young. But in Kentucky, Clarence Wells described his mother’s peach pickles as simply “the best,” with a “real good flavor” generated from cinnamon sticks and cloves that studded the fruit. Better, best, and good are common evaluative adjectives, as when Margaret Jarvis explained that she missed the wood stove still being used in her mother’s house, which produced better food because it cooked slower. This narrow vocabulary does not reflect careless or indistinct preferences. Jarvis noted that most of her co-workers at the Hanes factory also canned in the early 1970s, choosing the flavors and textures of food preserved at home even if store-bought goods were more convenient. Her mother Carrie concurred. It was possible that people along the Blue Ridge tended to bottle food in part because (if they had a garden) they could “raise it cheaper than they can buy it.” But, she continued, “I know it’s a whole lot better” in terms of taste.24

Convenience-as-defined-by-commercial-entities did not dictate Severt’s choices: she avoided a popular twenty-minute apple butter recipe that used vinegar to speed the process, saying she disliked the “funny whang” introduced by the acid, and chose to maximize efficiency in other ways. For example, like many she bottled plain fruit juice in the late summer and fall so that she could boil it into jelly later in the year—thus deferring some labor to a less hectic season. But the move also improved the final product’s texture and flavor: fresher jelly, she said, is “better jelly.” Rovertie Wills, too, preferred to preserve her own fruits and vegetables even after she could easily obtain their commercial equivalents; food she put up herself in her West Virginia kitchen in the late 1970s was “cleaner” and tasted “better.” Wills said little about the actual taste of her food, noting merely that she seasoned to personal preference, without measuring.25

I don’t know whether [laughing] you would or not, but I do. I love it.

This reluctance to wax specific about the taste of food may indicate the presence of a shared aesthetic that has needed little overt articulation. For instance, in her 1978 conversation with Johnson, Severt noted that she liked to make and eat tomato butter (cooked down with sugar and a mix of spices, including brown sugar, cloves, cinnamon, and allspice) on buttered biscuits, even though it took a long time to reduce the watery fruit. “But it’s good when you get it fixed,” she said. “Or I like it, now—I don’t know whether [laughing] you would or not, but I do. I love it.” Severt’s comment marks the outsider status of the interviewer (“who knows what you and your people prefer?”); it may also reflect a stance of humility that does more than subordinate the speaker. That is, canning materials from Appalachia seem careful to avoid dictating the choices of others, thus acknowledging the agency and creative control of individual cooks. “Seasoning to taste” is one way to emphasize discretion and skill, but there are other ways to avoid being prescriptive. In her preservation guide, Postell notes that the choice between apple cider or white vinegar is “up to you and your recipe,” while an “end of the season” vegetable soup can absorb whatever types and quantities of produce are available. Rhubarb should be cut to “convenient lengths,” cabbage chopped to “desired size,” and fruit butters cooked to “desired thickness.” One need not be fussy about the technology used to strain jelly—a clean flour sack or white cloth, a jelly bag, or a double thickness of cheesecloth will do, so long as one doesn’t mar the clarity of the final product by squeezing the jelly bag.26

This emphasis on “doing what works for you” operates within a broader aesthetic that privileges a uniform, harmonious, and visual regularity, if the canning guidelines of state and county fairs offer any indication. In 2006, for instance, West Virginia’s Ritchie County Fair awarded premiums to jars that were standard in size and shape and contained a product that was “evenly ripened and mature, without defects or spoilage,” and boasted a “clear bright appearance”; points were also awarded for “practicality of pack, uniformity of pieces and fruits, fullness of jars, [and] amount of liquid in jars.” Postell’s advice about how to keep plums from bursting, and strawberries and other fruit from floating, work in the service of these guidelines. They reward functional soundness: clear liquid is unlikely to be contaminated by yeasts and molds, and tightly packed fruit ensures most efficient use of available resources. But attention to these standards also produces an array that is visually appealing in its combination of regularity and variation.27

Indeed, it is the visual aspect of home-canned foods that generates the most detailed talk in the accounts that I’ve reviewed. Peaches and apples should be light in color, an outcome accomplished by adding vinegar, salt, or, more recently, lemon juice as the fruit is being prepared; working quickly also helps preserve color, even as it ensures that texture, flavor, and vitamins are retained. Addie Mae Dotson—who arranged potted plants along her porch and planted flowers within rings created by glass insulators in her Mississippi yard—was upset that she’d had to let her peeled peaches sit overnight, thus discoloring the syrup: “The liquor ain’t got no business lookin dark like that,” she said. “Liquor supposed to be clear.”28

Pretty is the adjective often used with reference to jarred goods and is closely linked to clarity and color. Carrie Severt was pleased that her peach preserves had “turned out pretty,” tinted a rosy pink from the fibers around the pits; she also infused her apple butter with color and flavor by adding red cinnamon candies, and was glad that her apple jelly was pretty and clear. Rovertie Wills noted that yellow transparent apples made a “good” jelly—but one so clear that it might be mistaken for oil. She added red food coloring so that it could play to best effect in the light. Because cucumbers don’t “stay pretty and green once they’ve been heated,” Margaret Jarvis brightened her lime pickles with green dye; turmeric gave her sweet pickles a yellowish hue. “All the turmeric does,” she said, “is makes it pretty.” Even jar choice can contribute to an appealing appearance: One 1931 home canning manual recommended using flint (clear) bottles if a homemaker intended to sell or exhibit her goods, although green foods such as pickles had “their brilliancy heightened by a slightly green tinge of the glass jar.”29

All the turmeric does is makes it pretty.

Display is, in fact, an important part of the whole endeavor. Wills intended her cellar shelves to “be handy and look pretty” and carefully worked toward this end even after the processing itself was finished. She told Katherine Martin in 1979 that she sorted the jars by general categories, by specific contents, and then by color, so that all peaches took their place within the fruit section, with white peaches to the left of the golden ones, each of them hot-packed by nested halves in order to assure a full, tight arrangement within each jar. Jams and jellies shifted gradually across the shelves from the deep reds of raspberry preserves to the purples of grape jelly and the dense darkness of blackberry jam. Among the vegetables, Wills enhanced the intensity of the beets by waiting to trim the tops completely until after the roots had been boiled, and she added texture and rhythm to her shelves with the vertical lines of corn canned whole on the cob. Preferring to hull beans whose pods were defaced before adding them to the prettier cut ones, her jars displayed a Morse code of dots and dashes.

Martin observed that a sense of “order, cleanliness, and simplicity” suffused Wills’s preparation, packing, and processing of filled jars, and even extended throughout the year, as she dusted the bottles and cleaned the cellar floor once a week. Her emphasis on the visual was socially advantageous, since it was the habit of her friends and neighbors in West Virginia’s coal country to visit and admire each others’ pantries; Wills even took her employer’s daughter and her children’s school teacher on tours of her cellar. Margaret Jarvis in North Carolina also liked the appearance of canned goods, arranging her bottles by type and color, periodically dusting them so they wouldn’t “look bad,” even though she kept her jars in cellar bins instead of shelves. Similarly—and like all the other women Katherine Roberts canned with during her research in Ritchie County, West Virginia—in 2004 Artus Wilkinson set her hot finished jars on clean, white dishcloths after processing, even though any absorbent buffer would have been sufficient.30

“But yet it’s got that taste”:

Claiming Agency and Community

In 2012, Slate published another article examining recent crafting enthusiasm; the author, Britt Peterson, had encountered an early Foxfire book, the publication produced by Eliot Wigginton and his students at Rabun Gap, Georgia, from materials collected as they interviewed and worked alongside local residents in the late 1960s. After examining the publication, Peterson described photos of an apple butter scene, using language that emphasizes brokenness, backwardness, and inattention:

A woman in curlers pours the contents of a battered tin pot into a jar. A hunched woman in a leisure suit and a gray pouf dumps five pounds of sugar into a vat boiling over an open flame. Nearby, an equally hunched man with roughened, wrinkled skin plays the banjo.

Then she contrasted the ostensible authenticity of these elders with the polished “play-acting” of contemporary diyers who blog about their forays into self-sufficiency with “gorgeous photos and a feisty, earnest attitude,” foodies who see foraging as “pleasurable games” rather than “a way of life for hungry people who need the nourishment they find in sidewalk cracks to survive.” Peterson warned that by fostering a false nostalgia for an imagined self-sufficient rural life, “farmer groupies” besotted with heirloom tastes mask the larger structural challenges of making a living in small-scale farming, including the difficulty of purchasing affordable fertile land and battling powerful corporate interests. While her attention to these structural issues is important, her framing is problematic: it is too simple to align play and agency primarily with the (wealthy post-)urban present and desperate survival with the rural past.31

People in the southern records I’ve studied recognize that their decisions to preserve food at home are indeed influenced by external factors, including time and available technology. Margaret Jarvis had once bottled wilted, salted mustard greens, as well as corn and peas, but by the late 1970s—although she preferred the taste of the canned versions—she froze all three because it was quicker. Her mother Carrie noted that most people along the Blue Ridge had adopted a multi-pronged approach to food preservation that included drying, freezing, and canning. With regard to meat in particular, she said, “Most everybody puts it in the freezer, anymore. But I don’t have a freezer, and I have to can mine.”

As we have seen, these resource constraints have been romanticized by some and pitied by others—a fact that is not lost on the objects of this external observation and speculation. At one point while conversing with her husband and their guests, for instance, Addie Mae Dotson noted her intention to help family in nearby Fayette, Mississippi, pick beans and peas, and talk turned to the wisdom and ways of being prepared. Many people bought peas from the store; others, like one of the Dotsons’ relatives, grew their own peas and froze them. “May gonna put that stuff up like me,” Dotson remarked, “but she sort of has a better way to put her’n up than I do cause she got two freezers and she fills em from the bottom to the top.” Her subsequent musings not only establish that she is familiar with home freezing procedures—they also acknowledge the stigma associated with her own method. “If I had a freezer,” she reflected, to the assenting murmurs of her husband and neighbor, “I’d do the same thing.

I wouldn’t can a minute.

I wouldn’t can no peaches up like I can em up. [Mmhmm]

I’d buy me plastic bags, and pack em in there,

and then put me some sugar on em, [Mmhmm]

and wrap em, [Yes]and drop em off in the freezer.

But I ain’t got no convenient way like that. [Mmhmm]

And I just go on and put em up, like my old poor parents used to put them up.

But laughing, she continued, “That’s all I want, something to eat!” She paused, summing up the suitability of her own methods. “Want something to eat, and let it be decent and clean. [That’s right] That’s all I want.” And then, rallying an aesthetic defense against critics, she shifted from utility to taste:

Well, one thing you can just stuff [something] in a freezer so long ‘til it’ll freeze the taste from it.

But you can put it in them jars, it ain’t gonna freeze the taste from it.

You ain’t gonna cook that taste out.It be right there.

It may be two or three years . . . set there two or three years

but yet it’s got that taste.

Likewise, Carrie Severt followed her statement about “having to can” meat with the assertion, “I love to can.” Sadie Miller, in West Virginia, dismissed the idea that canning had to be hard work at all, given adequate knowledge and skill. The hardest part about canning beets is harvesting them, she said; after boiling them, “Well, it’s a lotta fun to stand there and peel em like that, you know.” The skins slipped right off when rubbed. “Ooh, this is a messy job,” she mused as her hands brightened with magenta stain, “but you know, I love to do it.”32

Ooh, this is a messy job, but you know, I love to do it.

In part, these comments warn outside observers, “I know there are easier ways, but don’t pity or belittle me; don’t assume I haven’t made conscious choices about how I’ll manage my opportunities and challenges.” Paying attention to the talk of canners in the rural southern past and to its resonances in the present helps us to avoid assuming that play, pleasure, and beauty are the exclusive property of the young, urban, and well-to-do. Because these activities and loci of attention assume some measure of agency and choice, to align them with one group is to disempower the other.

Moreover, it’s dangerous to assume that contemporary DIY efforts are nothing more than play. Creative “making” can help to develop relationships that incur the mutual obligation so integral to “community”—even if the making itself is sporadic or solitary. Anthropologist Isabelle de Solier suggests that recent foodie and DIY identities have emerged in response to the largely abstract products of post-industrial white-collar labor. In this view, the homemade condiments being placed in urban pantries and circulated among far-flung friends help compensate for the physical, emotional, and social costs incurred during office work. Still grounded in smallness and exchange, interactions in these networks are organized around interests not always rooted in place, and smallness becomes a way to consolidate influence in a pluralistic society. Just as bragging on beautiful bottles is not limited to contemporary catered canning parties in Nashville or Atlanta, meaningful social units need not be determined by geography. In fact, a person might develop an important relationship with someone he knows only via a blog—or a jar of blueberry marmalade sent through the mail.33

Finally, if some Millennials or Echo Boomers—members of the large cohort born between 1980 and the early 2000s—are making new communities through long-distance or virtual exchanges, others—including a whole slew of “new generation” canners in the South—are staking clear claims to place through home food preservation. Socially engaged creators like Travis Milton and April McGreger, for instance, work to eschew labels like hipster and narcissist, which are often used to dismiss the contributions of their peers. Initiating “conversations with tradition” as they draw on childhood experiences in rural Virginia and Mississippi, they champion locally distinctive ingredients and locally resonant social practices without feeling compelled to constrain their own aesthetic preferences or to disavow the diverse cultural influences that characterize life in a connected, contemporary South. Milton offers diners at Comfort Restaurant in Richmond, Virginia, his take on his grandmother’s recipe for sour corn, or serves up fried catfish with tomato gravy he bottled in late summer. McGreger produces small batches of seasonal goods—sunchoke pickles, blueberry elderflower jam—for customers who encounter her in person, online, or as part of a long-term subscription; she adds new flavors to old processes and regional staple foods as she works through the year. Both Milton and McGreger respect locally responsive, skilled, and beautiful hands-on labor, and they find precedent for these attitudes and approaches in the lives of their teachers. Like other southerners, past and present, who have worked to shape and maximize economic, physical, and social resources in the region, these entrepreneurs belie assumptions that variety, pleasure, and choice are necessarily exclusive to particular spaces, times, or people.34

This essay first appeared in the Spring 2015 Food Issue (vol. 21, no. 1).

Danille Elise Christensen earned a PhD in Folklore and American Studies from Indiana University, Bloomington; her research centers on the ways that hierarchies of value (and values) are communicated in everyday talk, action, and artistry. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Religion and Culture at Virginia Tech.NOTES

Research at the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, was supported by the Gerald E. and Corinne L. Parsons Fund for Ethnography. Many thanks to the archivists at the AFC and at UNC’s Wilson Library who helped me access crucial documents, to staff at Southern Cultures who located images and refined my prose, and to all the readers who offered valuable feedback on the structure and content of this essay. Any oversights or omissions are mine.

- Drake Hokanson and Carol Kratz, Purebred & Homegrown: America’s County Fairs (Madison, WI: Terrace Books, 2008), 76.

- Liana Krissoff, Canning for a New Generation: Bold Fresh Flavors for the Modern Pantry (New York: Stewart, Tabori, and Chang, 2010), 10–11, 166; Katie Doolan, “Local Cookbook Author Relies on Seasonal Produce,” Lincoln Journal Star, May 27, 2014.

- Sara Dickerman, “Can It,” Slate, March 10, 2010.

- Anne Van Willigen and John Van Willigen, Food and Everyday Life on Kentucky Family Farms, 1920–1950 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006), 241; Lloyd Alter, “13 Great Posters on Preserving Food, When It Was Life or Death,” TreeHugger, September 26, 2012, accessed December 27, 2013, http://www.treehugger.com/slideshows/green-food/can-all-you-can-13-great-posters-when-preserving-was-matter-life-and-death/; Emily Matchar, Homeward Bound: Why Women Are Embracing the New Domesticity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 97; Chuck Reece, “Creamed Corn and the Truth,” The Bitter Southerner, September 30, 2014, http://bittersoutherner.com/preserving-place/#.VEVdAFY_EpE.

- “Bottling” is often used interchangeably with “canning,” but “canning” doesn’t always mean “bottling.” It can also refer to things sealed in “tin” cans, especially in the first half of the twentieth century; John L. Robinson, Living Hard: Southern Americans in the Great Depression (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1981), 132; Sarah Bowen, Sinikka Elliott, and Joslyn Brenton, “The Joy of Cooking?” Contexts 13 (2014): 20–25. On “fractionated” economies in rural West Virginia, see Katherine R. Roberts, “The Art of Staying Put: Managing Land and Minerals in Rural America,” Journal of American Folklore 126 (2013): 407–33. In The Livelihood of Kin: Making Ends Meet “The Kentucky Way,” Rhoda H. Halperin documented similarly complex and interconnected strategies—combining wage labor, entrepreneurial ventures in periodic marketplaces, local food production and foraging, creative reuse, and trading of goods and services—in the 1980s (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990).

- Photos of the Dotsons and their home can be found in image folders PF-20367/938-956, in the William R. Ferris Collection (#20367), Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Libraries; Judy Peiser and William Ferris, Bottle Up and Go, ½” color video (Memphis: Center for the Study of Southern Culture, 1980).

- Ferris Collection, folder PF-20367/938; folder 2996, reel 5, tape 17, pages 4–5.

- Ferris Collection, folder 2970, reel 1, tape 1, p. 11; folder 2996, reel 5, tape 17, p. 5.

- Ethel Dixon, Big Mama’s Old Black Pot Recipes (Alexandria, LA: Stoke Gabriel Enterprises, 1987).

- Ibid., 36, 3.

- Dixon, Old Black Pot, 36. On “craft satisfaction,” see Susan Strasser, Never Done: A History of American Housework (New York: Pantheon Books, 1982). On the social value of work and self-sufficiency—which has been especially well documented in the mountain South—see Patricia D. Beaver, Rural Community in the Appalachian South (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1986); Halperin, Livelihood of Kin; Lu Ann Jones, Mama Learned Us to Work: Farm Women in the New South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Katherine R. Roberts, “Storehouses of Abundance and Loss: Architecture, Narrative and Memory in West Virginia” (PhD diss., Indiana University, Bloomington, 2006); Patricia Sawin, Listening for a Life: A Dialogic Ethnography of Bessie Eldreth through Her Songs and Stories (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2004).

- Sadie Miller, Interview, Tape AFC 1999/008 SR123, Coal River Folklife Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Katherine Rosser Martin, “Food Preservation and the Folk Aesthetic,” Kentucky Folklore Record 25 (1979): 1–5.

- Roberts, “Storehouses”; Carrie Severt, Interview, AFS 21483-21484, Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project (AFC 1982/009), American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- Van Willigen, Food in Everyday Life, 219; Lesa Postell, Appalachian Traditions: Mountain Ways of Canning, Pickling & Drying (Whittier, NC: Ammons Communications, 1999), 8–9, 11.

- Margaret Severt Jarvis, Interview, AFS 21479-21482, Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project (AFC 1982/009), American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- Severt interview; Dixon, Old Black Pot, 36–37, 71. Cf. reflections on the distribution of surplus garden produce in Richard Westmacott, “The Gardens of African-Americans in the Rural South,” in The Vernacular Garden, ed. J. Hunt and J. Wolschke-Bulmahn (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1993), 77–105.

- Ferris Collection, folder 2996, reel 5, tape 17, p. 1; folder 2973, reel 3, tape 10, pages 8–11; folder 2998, reel 6, tape 25, p. 6.

- Miller interview.

- Postell, Appalachian Traditions, 56, 27; van Willigen, Food and Everyday Life, 219; Severt interview.

- Roberts, “Storehouses,” 90; Halperin, Livelihood of Kin, 12; Carl and Mary Thompson, Interview H-0182, Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007), Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Libraries, p. 13, 49. See also Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, James Leloudis, Robert Korstad, Mary Murphy, Lu Ann Jones, and Christopher B. Daly, Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987).

- Ferris Collection, folder 2998, reel 6, tape 25, p. 5.

- Dickerman, “Can It.”

- S. T. Rorer, Canning and Preserving (Philadelphia: Arnold and CP, 1887); Abby Fisher, What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking: Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc., with historical notes by Karen Hess (Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1995); Rafia Zafar, “What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking,” Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture 1, no. 4 (2001): 88–90; “We Can Pickle That!” Portlandia, season 2, episode 1, IFC network, 2012.

- Van Willigen, Food and Everyday Life, 220; Jarvis interview; Severt interview.

- Severt interview; Martin, “Folk Aesthetic,” 2–3, 5.

- Severt interview; Postell, Appalachian Traditions, 63, 26, 36, 20, 52, 42.

- The Ritchie Gazette and Cairo Standard, Wednesday, July 19, 2006:1-B, in Roberts, “Storehouses,” 101; cf. Leslie Prosterman, Ordinary Lives, Festival Days: Aesthetics at the Midwest County Fair (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995); Hokanson and Kratz, Purebred & Homegrown.

- Ferris Collection, folder 2996, reel 5, tape 17, p. 8. It’s unclear from the archived records why she wasn’t able to finish the peaches on her optimal timeline; she seems to have begun the process on a Sunday (against her better judgment), and the complications of coordinating the process with a film crew on multiple days may have contributed to the mishap.

- Severt interview; Martin, “Folk Aesthetic,” 4, 2; Jarvis interview; The Home Canner’s Text Book: Practical up-to-Date Recipes for Canning, Preserving, Pickling and Jellymaking, Rev. ed. (Boston: Woven Hose & Rubber Co, 1931), 7.

- Martin, “Folk Aesthetic”; Jarvis interview; Roberts, “Storehouses,” 98.

- Britt Peterson, “Farmer Groupies and Chicken Coddlers: The Foxfire Books and the Paradox of the Modern DIY Movement,” Slate, January 24, 2012.

- Ferris Collection, folder 2979, reel 8, tape 32, p. 3; Severt interview; Miller interview.

- Isabelle de Solier, Food and the Self: Consumption, Production and Material Culture (London: Bloomsbury, 2013); Preserving Now workshops and parties are described at http://preservingnow.com/.

- For more on Milton’s ethic and practice, see Travis Milton, “The Welcome Table: Simmering Food Talk,” The Daily Yonder, June 6, 2014, http://www.dailyyonder.com/welcome-table-food-talk-simmers/2014/06/02/7419 and Katie Hoffman, “Everything Tastes Better When You Share It: Travis Milton, the Daily Yonder, and Preserving the Best of Appalachian Food-ways,” Appalworks, June 3, 2014, http://www.appalworks.com/everything-tastes-better-when-you-share-it-travis-milton-the-daily-yonder-and-preserving-the-best-of-appalachian-foodways/. On McGreger, see Whitney Brown, “Eat It To Save It: April McGreger in Conversation with Tradition,” Southern Cultures 15, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 93–102 and Andrea Weigl, “Farmer’s Daughter Launches ‘Community-Supported Preservery,’” Raleigh News & Observer, April 26, 2014, http://www.newsobserver.com/2014/04/26/3811097/farmers-daughter-launches-community.html.