“The strumming of stringed instruments booms out through the PA, elaborate fiddle melodies erupt, followed by the soaring voice of the poet-practitioner, embracing those present, scanning the scene before him . . . drifting, shaping, moving verses that elicit a chorus of gritos.”

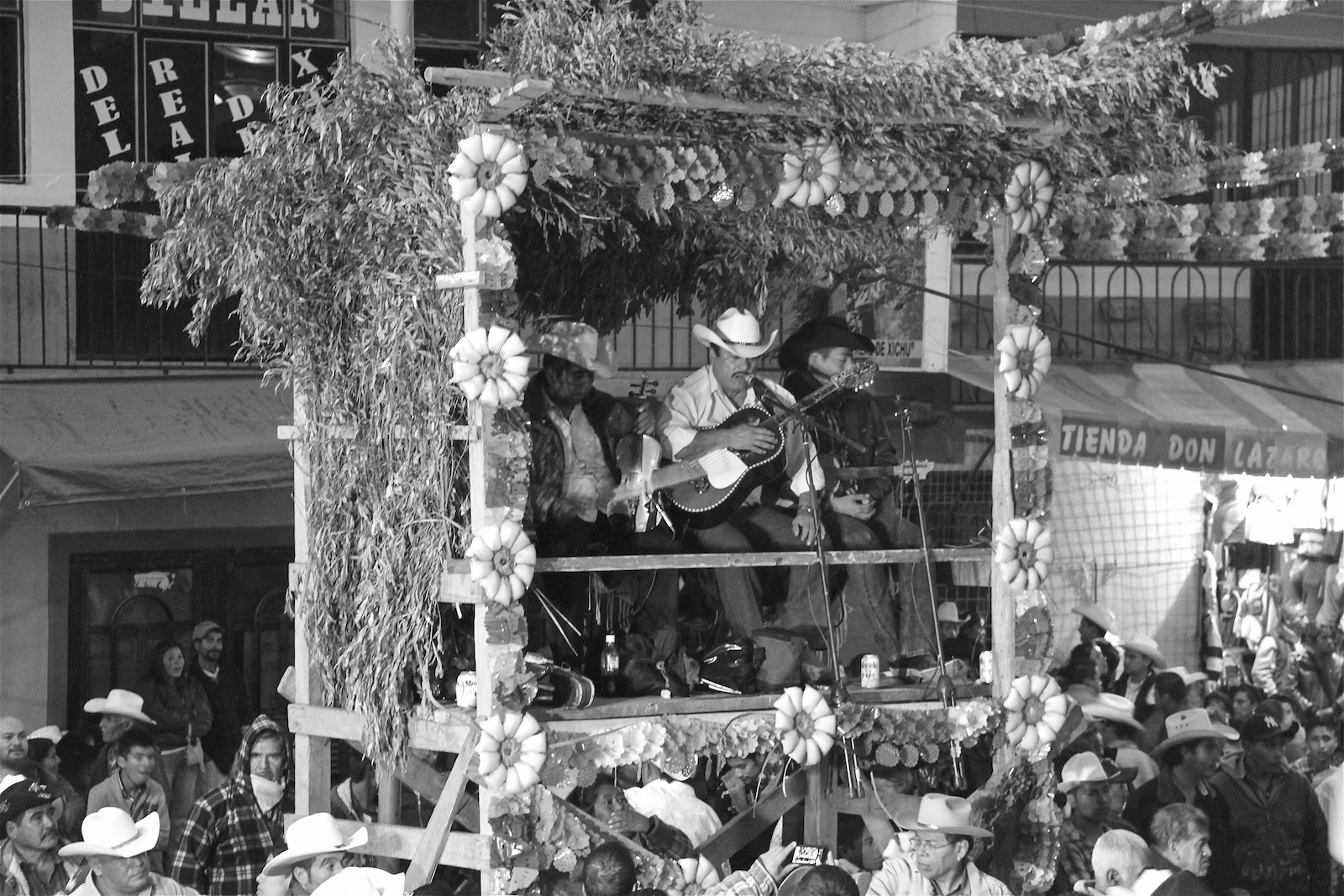

It’s a typical sweltering July evening in central Texas, close to ten o’clock. The incandescent buzz of city lights in the distance washes over the night sky, an amber glow that crowns the ballroom outside of town where an anxious gathering of Mexican migrants saunters along concrete bleachers; some lean out across the flanking metal railing and peer toward the crowd of several hundred below. The buzz of laughter and conversation nervously crescendos every now and then in anticipation of the musical performance everyone is awaiting. These soon-to-be dancers are nestled between two tablados (raised benches) positioned at opposite ends of the dance floor.

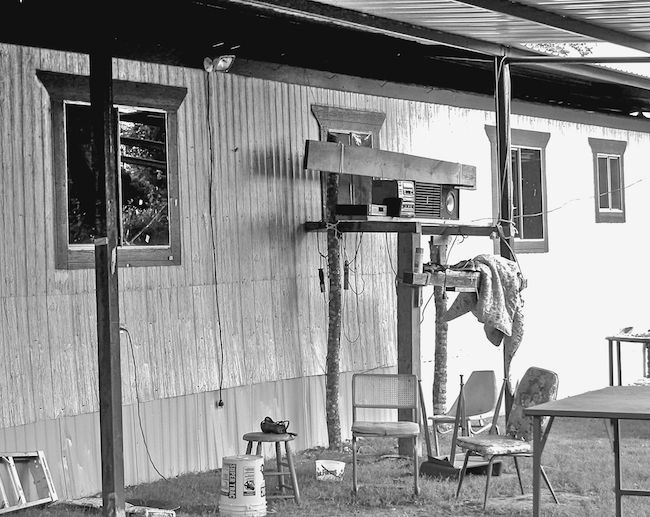

A few of the musicians drove in from northern Mississippi for the night—just south of the Tennessee border. It’s hard to imagine, considering Hurricane Katrina pounded the Gulf Coast a mere two weeks prior. Fallen trees and downed power lines marked the damage. Surely—they knowingly anticipate—they will be folded into the rapid response labor force required to clean up and repair the region. They already work construction, pave roads, and plant pine trees in those parts. A few years later I’d find that most would make the move up to Tennessee: “En Mississippi ya no hay gente, se han ido a Memphis . . . se puso dura la ley.” (There aren’t that many people in Mississippi, they’ve all gone to Memphis . . . the law [local authorities] got tough.)

En Mississippi ya no hay gente, se han ido a Memphis . . . se puso dura la ley.

There aren’t that many people in Mississippi, they’ve all gone to Memphis . . . the law [local authorities] got tough.

Four silhouettes appear on one tablado, moving leisurely, but with purpose, positioning themselves with their instruments—two violins, a guitarra quinta huapanguera (eight-string bass-guitar), and a vihuela (small five-stringed chordophone). They assume their positions, exchange glances, quietly confer, subtly coaxing the music soon to be produced. They gaze over at the tablado yonder, now similarly occupied by a matching ensemble, waiting patiently. The audience instinctively focuses on the shadows that have emerged above them. And as if without warning, the strumming of stringed instruments booms out through the PA, elaborate fiddle melodies erupt, followed by the soaring voice of the poet-practitioner, embracing those present, scanning the scene before him, his mind weaving through the audience, drifting, shaping, moving verses that elicit a chorus of gritos (shrill cries of emotional release). The moment grows dense, binding, stretching, reaching, as his improvised poetics skillfully layer the present-tense currency of this time and place with that of far away rural communities in central Mexico.

In an era marked by intensified Mexican migration to the United States, linked to increased transnational economic integration between both countries in the guise of “free trade,” the free movement of people across the U.S.–Mexico border is ever-more restricted as that geography becomes outrageously militarized; and this gathering is that which thrives, as displaced families cross the border clandestinely in efforts to improve their life chances and mitigate the “ruins of NAFTA”—despite the low-intensity violence mobilized against them.1 Dancers bend long and pivot rapidly, shaking and twisting. Their inertia extends out to different parts of the body only to tumble back to its core, giving off heat, exchanging energy, carefully patterning their individual movements, shadowing those of others, heads bobbing up and down or thrown back, arms swinging, hands swaying, bottoms rocking back and forth, huffing and puffing along. Steps grow louder, building a sonic wake that mirrors the vigorous bowing and strumming of the musicians. Its tones sweep across the skin and its utterances linger, caught in the air, fading, but slowly, as the poets dynamically maneuver between the warmth of the gathering and distant places, crafting poetics that are close at hand, that pull things into view, tracing the assemblages and trajectories of Mexican migrant life.

The poets dynamically maneuver between the warmth of the gathering and distant places, crafting poetics that are close at hand, that pull things into view, tracing the assemblages and trajectories of Mexican migrant life.

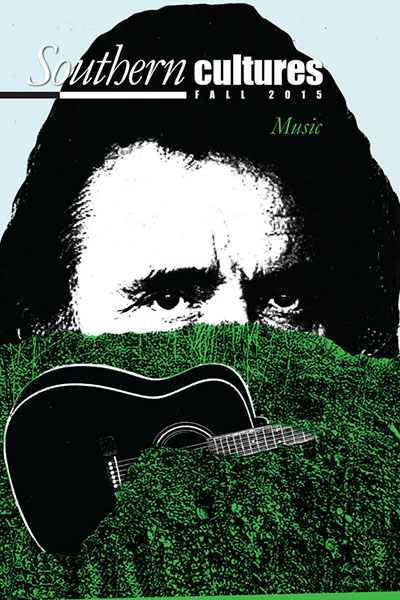

A music relatively unknown outside its region of origin in the Mexican states of Guanajuato, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí, huapango arribeño takes its name from the Nahuatl word cuauhpanco—signifying the expression “atop of the wood,” which is a reference to the tarima (wooden platform) atop which people dance zapateado (patterned footwork) to various styles of vernacular Mexican music. The term arribeño (highlander) is a reference to the mountainous region of the states of Guanajuato and Querétaro (known as La Sierra Gorda) and also to the mid-region of San Luis Potosí (La Zona Media). Huapango is typically placed beneath the arch of what is considered son, or string-music, in academic circles, which, to a degree, distinguishes huapango from other genres of Mexican music: the corrido (Mexican ballad), the canción ranchera (country song), the accordion-driven norteña of northern Mexico, and the brass and woodwind banda popular of the Pacific Coast region.

The term huapango is often invoked in reference to the signature galloping 6/8 rhythm typical to the style. This and other features make it familiar and recognizable. Many ethnic Mexicans and appreciators of Mexican music know huapango when they hear it in all of its variations, whether it be via the accordion-based stylings of Mexico’s música norteña or rendered in dramatic bel canto flare by the immortal stars of the golden era of Mexican cinema. While deemed an emblematic sound of assumed national tradition during this period, the historical origins of huapango, more broadly, as a regional music parallel that of adjacent styles such as the son jarocho from Veracruz, meaning these musics are at their core mestizo, the product of centuries of culture building, not ready-made emblems.

One of huapango arribeño’s most salient features is the use of the Spanish décima, or ten-line stanza, as poet-practitioners use the form to assemble poetic narratives. And it is best expressed during topada performances, which are organized for any number of celebratory occasions. The name topada comes from the verb topar—to collide with—and signifies the heightened reciprocity and intensity of such encounters. There, two huapango arribeño ensembles face one another, engaging in a marathon musical and poetic duel that lasts for hours. During the performance, both groups—made up of two violins (a lead and second fiddle, or primer and segunda vara), a guitarra quinta huapanguera, and vihuela or jarana (small five-stringed chordophones)—tower above the audience atop tablados, one at each end of the dance floor, physically facing each other while a sea of people dance rhythmically up and down below them. A detailed code of etiquette guides this performative encounter, such that both ensembles are responsible for bringing to bear an array of musical and poetic resources. Audiences expect to be fully engaged, taking on an evaluative role, and practitioners must fully adhere to this responsibility, for people desire (and thus make real and necessary) these laborious bursts of musical and discursive energy. As of late, the transnational world of huapango arribeño extends across central and east Texas, to Mississippi, Tennessee, and northern Florida, telling of life in these places, out loud, building bridges, and staking claims “South” of the border.

As of late, the transnational world of huapango arribeño extends across central and east Texas, to Mississippi, Tennessee, and northern Florida, telling of life in these places, out loud, building bridges, and staking claims “South” of the border.

Historian Julie Weise challenges the view that Mexican migration to the American South is a new phenomenon and thus questions the premise of what some scholars have termed the Nuevo South—a play on Henry Grady’s famous proclamation in 1886 that the South was “New.”2 At the turn of the twentieth century—in the wake of the Mexican Revolution, to be precise—Mexicans and Mexican-Americans began migrating to the region in substantial numbers (Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas, to name a few places) as they followed labor contractors to sugar parishes and cotton plantations, mainly, both encountering and, at times, successfully navigating Jim Crow. This migration continued through the era of the Bracero Program—the bi-national labor recruitment program between Mexico and the United States from 1942–1964.

Our historical vision can extend yet even further. Indeed, one could argue that the opening up of the American West is deeply tied to the American South. The historical terrain connecting these geographies extends to the nineteenth century, an era marked by North American encroachment into Mexican territory. As José E. Limón comments: “One might say that the American south served as midwife—and not a gentle one—at the birth of Greater Mexico.”3 It was largely “white Southerners in the company of their black slaves who were the first Americans to appear en masse in Texas” in the early 1820s, as the Mexican government permitted controlled American immigration into the sparsely populated areas of central and east Texas.4 Soon after, the demands of the southern political economy—namely, cotton production and slavery—helped catalyze the Texas independence movement of 1836, which sparked a series of events that culminated in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). As historian Clement Eaton writes, “The Mexican War was an adventure in imperialism of the South in partnership with the restless inhabitants of the West. It was provoked by a Southern President and fought largely by Southern generals and Southern volunteers.”5

The expansion of slavery into newly ceded territories and a shift in the balance of power between slave and non-slave states inflamed the regional conflict between the North and South—the Civil War was fought only thirteen years after the Mexican–American War.6 And now, as a multitude of Latin American migrants arrive in increased numbers to the U.S. South, their presence represents the most recent wave of migration catalyzed by a set of asymmetrical political-economic conditions that American imperial desires have fomented.

Though tethered to the material and immaterial oscillations of the U.S.–Mexico Borderlands, a “Mexican South,” proper, exerts its own presence, as Mexican migration extends deeper into the U.S. South, assigning new meanings to that geography. Indeed, it helps if we think of a geographic boundary or border as an edge where a place (and likely multiple places) begins its “presencing,” so that even places that aren’t adjacent or overlapping geographically can be culturally attuned to each other.7 In this way, practices—like music—that move from place to place with the people who engage in them, transform along those routes and carry the details of those movements referentially and pragmatically. Ultimately, these sounds, verses, and melodies transport and transcend, further transforming “The South,” which is itself a palimpsest of contested political histories and cultural discourses. At times, these competing representations reveal the lived-in gap between the theoretical universality of citizenship and its practical marginalizing effects.8 And amid this interstitial breach where “race” is equated with varying forms of second-class citizenship, Mexican migrants bring “culture” to bear in their expressive practices. In doing so, they challenge the assumed singularity of the nation-state through music and lyrical arrangements that construct multiple and overlapping imagined communities and disrupt the constructions of illegality and criminalization attached to undocumented migrants in the United States.

Understanding such negotiations requires attention to the shifting social contexts of the migrant experience, the ideological environment in which representations of the “migrant” circulate, and, finally, the politics their own aesthetic renderings of the matter of transnational living acquire. In other words, understanding how everyday embodied aesthetic acts transform that which some wish to be unconditional (like citizenship or the border) into something far more contingent and human. For the space of performance is compositional; it pulls together intimacies, gathers the most basic desires for recognition among clandestine bodies moving across borders and dance floors, and thus makes connections amid a political formation that circumscribes geographies and the rhythms of daily life. These photographs are scenes of such movements, of laboring bodies and the labor of performance, of the poetic bridging of multiple places across central Mexico and “The South,” remaking both along the way, voicing solidarities otherwise severed in an atmosphere marked by the intensified criminalization of migrants.

Consider the tensive center of a story full of multiple movements and arrivals across places, where vulnerable bodies bear witness to the vertigo of a precarious present. Consider the ways in which that story becomes itself storied, voiced publicly in all night performances in the company of hundreds, thousands, or sometimes only a few dozen friends. Consider how Mexican migrants become caught within this dramatic dispersal of public feelings and personal histories, folding in on themselves, taking hold as a transformative force. Consider, then, how a public comes into being through the aesthetic voicing of shared experiences, connecting to the sobering reality of clandestine border crossings; the sultry conviviality after a hard day’s work; the unthinkable shock of a loved one’s death; picking up the pieces after Hurricane Katrina; getting drunk and dancing alone for no particular reason; waiting for the weekly phone call from a relative on the other side of the border. Consider how the work of huapango arribeño practitioners is that of translating/story-ing this polyphonic connectivity, generating a new shared experience (through performance) where everyone present is bound up together in the same interpretational space of living in that moment (of performance). Consider all of this a cultural dialogics of self-authorization that places lives in relation to others no matter where they are and in the face of everyday borders, violences, and exclusions that reduce personhood, that dictate where home is, that tell “others” that they don’t belong in a place.

Consider how the work of huapango arribeño practitioners is that of translating/story-ing this polyphonic connectivity, generating a new shared experience (through performance) where everyone present is bound up together in the same interpretational space of living in that moment (of performance).

Alex E. Chávez is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Notre Dame. Centered around Mexico, the U.S.–Mexico Borderlands, and Latinas/os in the United States, his research explores the innermost workings of transnational migration, embodiment, and everyday life as manifest in political economies of performance with particular emphasis on music and language. His ethnographic study of huapango arribeño is the first of its kind and forms the basis of his book manuscript, ¡Huapango!: Mexican Music, Bordered Lives, and the Sounds of Crossing. He is presently lead consultant on a Smithsonian Folkways recording of huapango arribeño to be included in the world- renowned Tradiciones series.