In an essay published in our pages in 2000, our friend Jerry Leath Mills surveyed around 30 prominent twentieth-century southern authors, which led him “to conclude, without fear or refutation, that there is indeed a single, simple, litmus-like test for the quality of southernness in literature, one easily formulated into a question to be asked of any literary text and whose answer may be taken as definitive, delimiting, and final. The test is: Is there a dead mule in it?” For our forthcoming special issue on 21st-Century Fiction, we were curious if Mills’s hypothesis held up so we brought the question to some of our favorite authors. Is there a “quality of southernness” in 21st-century southern fiction? Is Mills’s mule now truly dead?

Responses from five of the sixteen authors we queried appear below. For the full selection, turn to the special zine inserted in our 21c Fiction Issue or access it online via Project Muse.

Allan Gurganus

I risk a prophecy: Not far into this century, a Faulkner-sized talent will emerge from among those very Latin American expatriates Donald Trump imagines he can wall away.

How will our New South look to a gifted narrator whose mother papoosed her across the Rio Grande? Aren’t we overdue a fresh perspective on our retread confederacy? Who’s better equipped than someone discovering the United States and the English language at the self-same time? She will have the brown eyes that can look straight through a blue-eyed culture.

William Faulkner’s sense of how much magic one hamlet can yield encouraged/engendered both Toni Morrison’s Ohio village and Garcia Marquez’s outpost Colombia. Now is the time for Faulkner’s narrative gift to boomerang back north. A talent capable of registering equatorial jungle and Nashville muffler shops is, even now, slouching toward us. She will bring tales of all the toxins, drug cravings, diet sodas, and unneeded baby formula we’ve exported. She will communicate in runic Mayan prototypes through Spanish Catholic fandangos toward Mississippi blues. She will offer something we long ago forgot to seek in our own boring cornpone jokes about ourselves.

She will finally show us US!

Allan Gurganus writes fiction and essays. He lives in his native North Carolina. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Jamie Quatro

The summer my collection came out I had lunch with Roger Hodge—then my editor at Oxford American. I’d never met him in person. He’d just read my book. We began with the requisite small talk over our salads, but when I mentioned that I’d moved to the South just seven years earlier, he put down his fork.

You’re not from Tennessee? he said. I grew up in Tucson, I said. But your work is so southern, he said.

I knew he was talking about more than the book’s setting. Later, when I told him I was raised Church of Christ—the mainstream, no-instruments, baptism-by-immersion variety—he said, Ah, now the southernness makes sense.

I’ve thought about that conversation often. I think Roger was onto something. When we moved to Chattanooga, no one needed to explain the churchgoers to me. I knew these people; they were my people. They were God-haunted as I was God-haunted, though our Wednesday night fellowship dinners took place amid mesquite and cactus, not dogwoods and magnolias. There was no escaping it: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, a transfusion in the blood, an infection or its cure—or both, depending on the day. Having learned to love the world through eyes that saw it as a beautifully painted but transient scrim behind which rose an eternal solidity, is it any wonder that whatever I embraced in my art would “struggle in my arms and declare itself pilgrim—disclosing, through the lattices and windows of its nature, another City”?

Prose that reaches out of itself towards it-knows-not-what; poetry bearing news from another country, even if the news is such a country does not exist; some God-haunted ache that asks the deepest questions and doesn’t give answers (plenty of clichéd southern literature does that and not one of us should trust it)—to me, this pulse has characterized, and continues to characterize, something deeply “southern” in literature. Even in those of us who can’t claim it by birth.

Jamie Quatro is the author of the story collection I Want To Show You More (Grove), a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction and the NBCC John Leonard Prize. A second collection and novel are forthcoming. A contributing editor at Oxford American, she lives in Lookout Mountain, Georgia.

Monique Truong

There’s not just one “dead mule” in 21st-century southern fiction. There are two, and both are alive, well, and kicking. One is named Secrecy and the other Hypocrisy. Their namesakes are the lingering effects and the adaptive requirements of White Supremacy, an ideology that twisted and warped the human heart, both of the enslaved people and the “masters.” It forced human beings to become property. It justified human beings to own said property. It treated cruelty as a matter of economics. It attempted to erase love, compassion, and empathy. You needed secrecy or hypocrisy, and often both, in order to survive. Long after the end of slavery, White Supremacy remained and entwined itself with a white nostalgia for the time before an irrevocable “loss.” Ask yourself, within this context, how does the South become whole again? Our history is our beasts of burden. Our imagination is where we attempt to harness them, or at least to call them by their names.

Monique Truong is a novelist and essayist. When her family came to the United States as refugees from the Vietnam War in 1975, they lived first in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, the setting of her novel Bitter in the Mouth. Her other novels include the national bestseller The Book of Salt and The Sweetest Fruits, forthcoming from Viking Books.

Megan Mayhew Bergman

As long as Mama, God, gossip, and poisonous snakes are in a southern writer’s childhood, we may well have southern literature. After all, the artist must have something to define herself against; to pick a fight with—like bad politics. Otherness, in our culture, has always been a fine ingredient for making writers. I don’t see that changing.

The last street I lived on in the South, I had the following neighbors: a stay-at-home dad, a sun-worshipper, a sixty-year-old NRA member whose mama still brought him dinner, two gay men with a convertible Porsche, an Iranian boarding house, and a drug dealer who liked to relax on the front porch in his underwear. What happens when we get together for a pig-pickin’? Work from the contemporary South must allow for that possibility, honor the complexity of our social fabric. Fresh and ambitious work from the South can no longer smear Vaseline across the azalea-dotted landscape and front porch tableaux—but tell us what was going wrong in the back room, at the bank, on the bus. What did Mama really say when the evangelist stuck one foot in the door?

Art is the best opportunity we have for addressing the ugly socio-political tensions that divide us. It’s time to make space for dangerous conversations, at the dinner table, at the pulpit, and on the page.

Megan Mayhew Bergman was raised in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, and lived in the South for thirty years before moving to her husband’s farm in Vermont. She’s published two books with Scribner, has been anthologized in Best American Short Stories, and is the Associate Director of the Bennington College MFA Program.

Randall Kenan

One of the best explanations I’ve heard, of what the American South is, was said by the late Reynolds Price. The South, he said, was an amalgam of the African American presence, a strong agricultural society, and the Protestant religion, and how these elements mixed and expressed themselves. There has always been a black presence in New England; California is one of the world’s biggest agricultural powers; Protestantism is a significant presence in the Pacific Northwest. None of them come anywhere near to being like the American South.

I suffer from a great worry, a clichéd worry, that what most people think of when they think of contemporary Southern Literature is a literature stuck in Nostalgia. Paeans to magnolias and moonshine, odes to grandma and porch sits, ghosts of the Civil War and dialects thick as molasses. Of course, everyone everywhere has grandmothers (who loves a grandmother more than the Irish, the Japanese, or the Russians?). Everybody gets drunk (Ditto). And what landscape is free from apparitions of civil strife?

It seems to me that the better millennial southern writers shun nostalgia and false historical romance. They write about the way we live now. They write about: hog factory farms, the growing immigrant community, health care, cell phone reception, free WiFi, and LGBT rights. Yes, they love farm-to-table and are besotted by craft beers, but that’s part of their flavor. Nonetheless, they are aware of and informed by the past. They really are the New South and represent our best hope to remain America’s most relevant, loud, high-spirited, authentic voice.

Randall Kenan is the author of A Visitation of Spirits, Let the Dead Bury Their Dead, Walking on Water: Black American Lives at the Turn of the 21st Century, The Fire This Time, and editor of The Cross of Redemption: The Uncollected Writings of James Baldwin. He is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Jill McCorkle

I think that the mule lives on in memory and that his big old carcass is often used to hold in place the histories and stories of those who have come before us; he has fertilized the ground, traces lingering if you dig deep enough, but he is no longer a part of the daily life as he once was. Our dead mule morphed into dead cars up on blocks to dead downtown areas, left to decay, to dead leaders who in the glare of contemporary light are being reexamined for their acts of bigotry and hatred. Death has always been front and center but that is true in all literature. But the mule represented more than that; genetically, it’s kind of a dead end even before it dies. It often plows the same field over and over or walks in an endless circle. It got the job done but it was focused on the same old business.

I think that southern literature reflects a much larger image these days. In fact, I don’t trust the literature that hasn’t grown beyond the easy tropes. If the tea is too sweet, or somebody is hollering for Memaw and Pepaw and Goober in the Chinaberry tree, I’m out of there. What I DO trust though is a sense of place and a love of place even when that love is complicated by the acceptance of a lot of history we are ashamed of. And I also trust and believe in the fine art of storytelling and the oral tradition that is alive and well in the South. But I think in the same breath, it is important to acknowledge that that oral tradition is one that often grows out of people who have been deprived a voice, be it by prejudice or illiteracy or alienation or some combination therein.

Though rare, there are mules who have successfully given birth to new life—just not the dead ones.

Jill McCorkle is the author of four story collections and six novels, most recently Life After Life. She has taught at Harvard, Brandeis, and North Carolina State University, and currently teaches in the Bennington College Writing Seminars. She lives in Hillsborough, NC with her husband, the photographer Tom Rankin, and the donkey they received as a wedding gift.

This article first appeared in the 21c Fiction issue (vol. 22, no. 3: Fall 2016). For more, join us at the launch of our 21st-Century Fiction Issue on October 29, 2016 at the 21C Museum Hotel in downtown Durham. Jill McCorkle will moderate a panel and continue the conversation started in our pages.

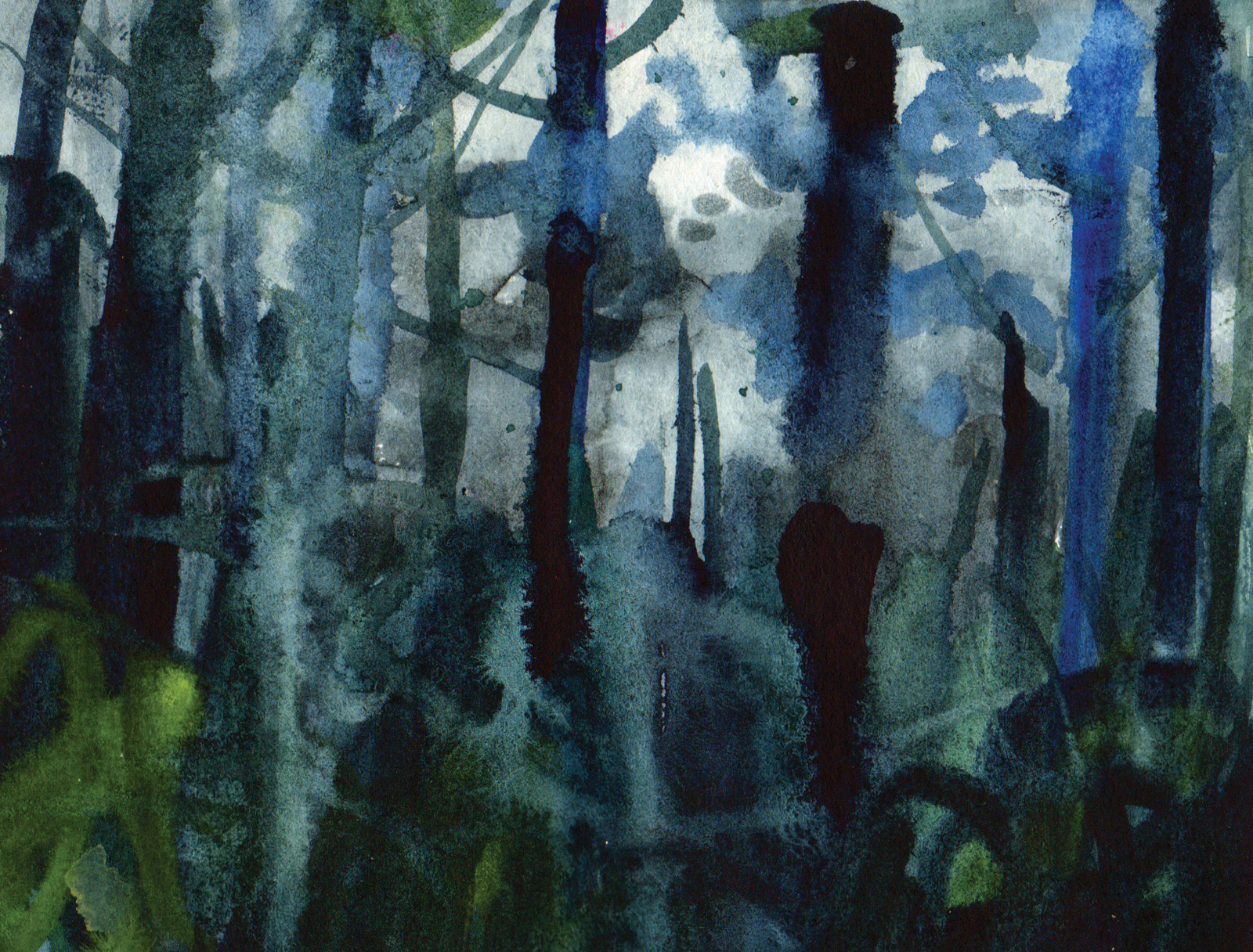

In addition to drawing and painting, Phil Blank spends his time playing music, reading books, and filling out paperwork. See more of his work here.