“‘All photographic imagery documents a moment gone—and I think much of my work is interested in that going, what is here and how it drifts to that gone place.’” —Tom Rankin

The following works were included in the exhibition People Get Ready: Southern Lens at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. The images coalesce around an untitled photograph from William Eggleston’s series The Democratic Forest. This photograph captures Eggleston’s “democratic” perspective that engaging imagery could be found in any subject at nearly every turn of the camera lens. Characteristic of many of Eggleston’s images, the narrative or subject appears to be at the center of the image at first glance but gradually extends to the edge of the photograph. While the harvested tomatoes, perhaps waiting to be washed, take center stage, a jumbled assortment of objects and what appears to be food covered by plastic wrap sit across the sink, not completely recognizable. Above them, at the very edge of the photograph, a tiny glimpse of grass is visible, hinting at an outdoor location. And barely captured within the frame, a rifle sits propped against the wall below two hanging dust masks. All of these objects allude to human activities and form a condensed sensory experience rich with narrative potential. Depending on the viewer’s perspective, for example, the rifle and masks could be construed as ominous symbols or as the mundane artifacts of rural life.1

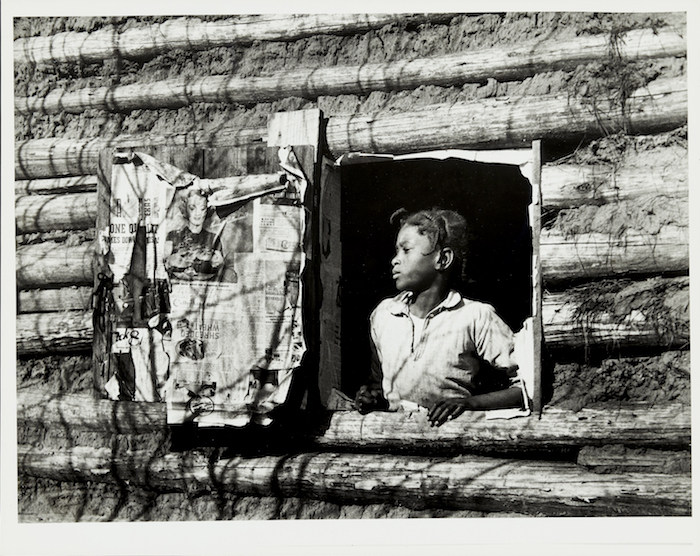

The other artists featured in Southern Lens likewise explore the South in its complexity through images of landscape, agriculture, and daily life. Historic photographs, such as Arthur Rothstein’s Girl at Gee’s Bend, Alabama, are juxtaposed alongside contemporary works, including one by Genevieve Gaignard, who, as a biracial artist, challenges notions of race and class in her subversive self-portrait by eschewing restrictive societal norms that marginalize individuals or require conformity. Everyday moments—cleaning fish or drinking beer—become still lifes in Jeff Whetstone and Henry Horenstein’s photographs. Eggleston’s carefully arranged tomatoes and Tom Rankin’s burial of an animal suggest human presence and activity not captured in the frame. Though few images offer overt connections to their southern location, elements of the landscapes, flora, and fauna connote a regional familiarity. Much the same way that Eggleston monumentalizes the quotidian, each of these photographers elevate and transform the ordinary to their advantage, hinting at deeper cultural narratives and allowing for imaginative possibilities.

Henry Clay Anderson captured images of everyday life in the middle-class black community of Greenville, Mississippi, at the height of Jim Crow. A local photographer who ran a studio in Greenville for over thirty years, Anderson’s work was not widely known outside of his community until hundreds of negatives and original prints—taken over the course of many decades—were discovered shortly before his death in 1998. In the mid-twentieth century, the visual narrative of Greenville and the surrounding Mississippi Delta region was largely framed by northern photographers who came to capture familiar tropes of slave descendants, segregation, and the adversity faced by African American southerners. Very few depicted thriving, prosperous middle-class black communities.2

Anderson was a pillar in his community, teaching school and at one point running for political office. He took pride in photographing his surroundings, capturing, in addition to formal portraits in his studio, local beauty pageants, weddings, community events, proms, and informal portraits in people’s homes. Motorcycle Riders was taken on the sidewalk outside of the photographer’s studio—the window advertisement reading “Anderson Photo Service” is just visible. During a turbulent time in American history, Anderson’s photographs celebrate Greenville’s black community by highlighting its resilience and complexity and by portraying its members at their aspirational best.3

Genevieve Gaignard blends performance, humor, kitsch, and popular culture to bring different characters and personas to life in her photographs. The child of a white mother and a black father, Gaignard frequently felt invisible growing up—that she did not belong or “pass” as either black or white. Gaignard draws upon her own biracial status to explore in her photographs the complexities of modern identity formation. Her work in many cases challenges implicit biases and re-contextualizes preconceived notions of race, class, gender, and identity.4

In Red State, Blue Plate, Gaignard alludes to both political and geographic stereotypes, providing clues without being heavy-handed. The artist, who often incorporates food in her images to signify class, here holds a bottle of Budweiser while a second beer and a pack of cigarettes sit on the car next to her. Parked in a nondescript wooded area, Gaignard does not provide definitive clues about her exact location despite the Massachusetts license plate. Nor does she necessarily confirm that she is in a red state; the first half of the title is perhaps a reference to her state of dress rather than geography. By appearing casually in flannel, boots, and a baseball cap, the artist plays to class stereotypes typically associated with so-called “red states.” By positing different possible narratives, Gaignard draws viewers in and provocatively leaves the conclusion open-ended, reinforcing the subjective nature of cultural boundaries and societal constructs.5

While Barkley Hendricks is best known for the large-scale revolutionary portraits of people of color that he began painting in the 1960s, the artist also maintained a thriving, diverse artistic practice that included photography, music, drawing, and collage alongside his work in painting. Hendricks gravitated toward photography prior to and while studying at Yale in the 1970s. At a time when few other painting students were making figurative work, Hendricks shared a certain affinity with the photography students and earned a coveted spot in Walker Evans’s photography class.6

A keen observer of daily life, Hendricks further illuminates his democratic artistic impulse in his photographs, as well as a keen desire to experiment with different techniques and media in documenting life around him. The same focus and acuity found in Hendricks’s paintings pervade his work in other media, as does a playfulness and interest in realism, composition, and portraiture that captures the subject’s personality. Much the same way that the artist’s painted portraits feel timeless, so too does North Carolina Sisters, despite being taken forty years ago. Captured during Hendricks’s trip to Durham in 1978 for the American Dance Festival, the photograph looks as though it could have been taken on any recent day in downtown Durham.

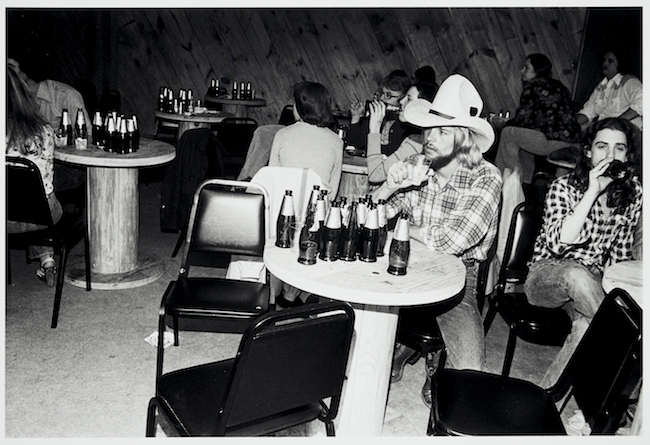

An avid music fan, Henry Horenstein has spent many years documenting musicians, their fans, local bars, and numerous other venues across the country. In particular, he is known for chronicling the 1970s and ’80s country music scene and for capturing stars such as Dolly Parton and Ernest Tubb. Though country music was by no means an exclusively southern phenomenon, Horenstein spent considerable time in the South, photographing in iconic country music cities such as Nashville and in small-town local scenes alike. Horenstein acknowledges that the ease with which he accessed backstage areas and captured candid portraits of singers is difficult to imagine today, given security restrictions and closely managed media access. Throughout his decades-long interest and immersion in the music world, Horenstein captured the evolution and unique cross-currents of American musical traditions. His photographs serve as a historical record of not only celebrity performers and music halls, but also—as illustrated in Still Life with Beers—as a testament to the simple, universal pleasure of gathering to enjoy music.7

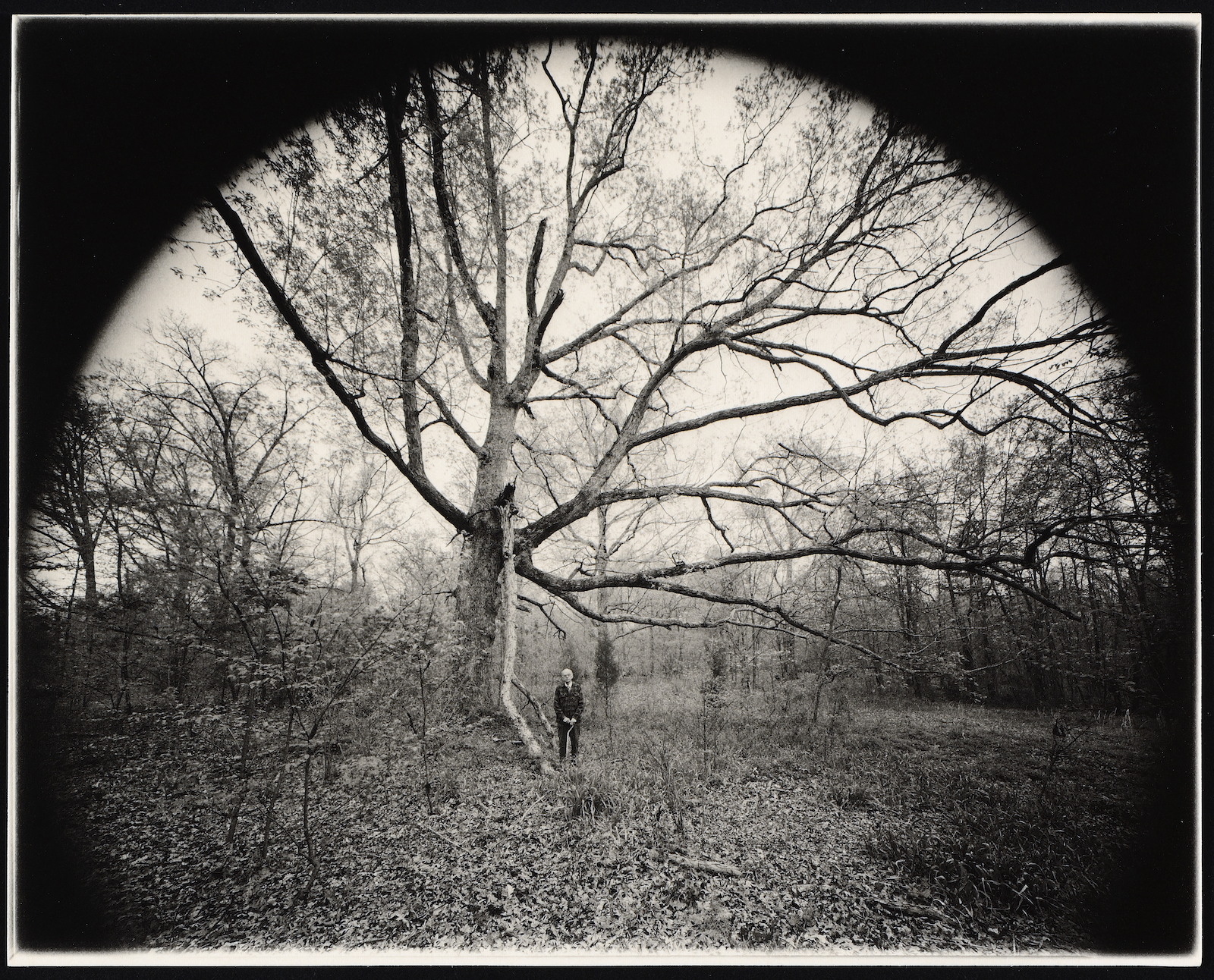

Tom Rankin has been documenting the American South for several decades with a particular interest in sacred spaces, community rituals, and narratives that build with the passage of time. The artist frequently returns to the same landmark or geographical area for years in a row to record the changes that occur. The memorialization of overlooked, forgotten, or seemingly small subjects is a prevalent motif in his work. Here, the artist, who raises goats, presents a caringly arranged burial of a baby goat that has died. The image taps into a shared familiarity and recalls the ritual of heartfelt burials of beloved family pets. Rankin elevates a quotidian fact of farm life into something that both captures and transcends the “injuries of time.” He says, “All photographic imagery documents a moment gone—and I think much of my work is interested in that going, what is here and how it drifts to that gone place.”8

Arthur Rothstein was part of the small but influential photography branch of the Farm Security Administration, which operated from 1937–1942. Begun as the Resettlement Administration in 1935 as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the agency created a loan program for farmers, provided resettlement assistance, and engaged in land renewal projects. Rothstein, alongside his now well-known colleagues Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and others, documented the plight of rural American agriculture throughout the Depression years. Buoyed by legislation passed in Congress in 1937, the fsa sent Rothstein to document the small rural community of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. Enclosed by water on three sides due to a dramatic curve in the Alabama River, Gee’s Bend was geographically isolated. Many of the residents were descended from slaves on the former Gee plantation and had become tenant farmers. Despite the patronizing approach frequently taken by the agency in allocating aid, Rothstein endeavored to portray the residents of Gee’s Bend with dignity, not as victims of past or present oppressions but as self-respecting people engaged in common (and thus relatable) routines.9

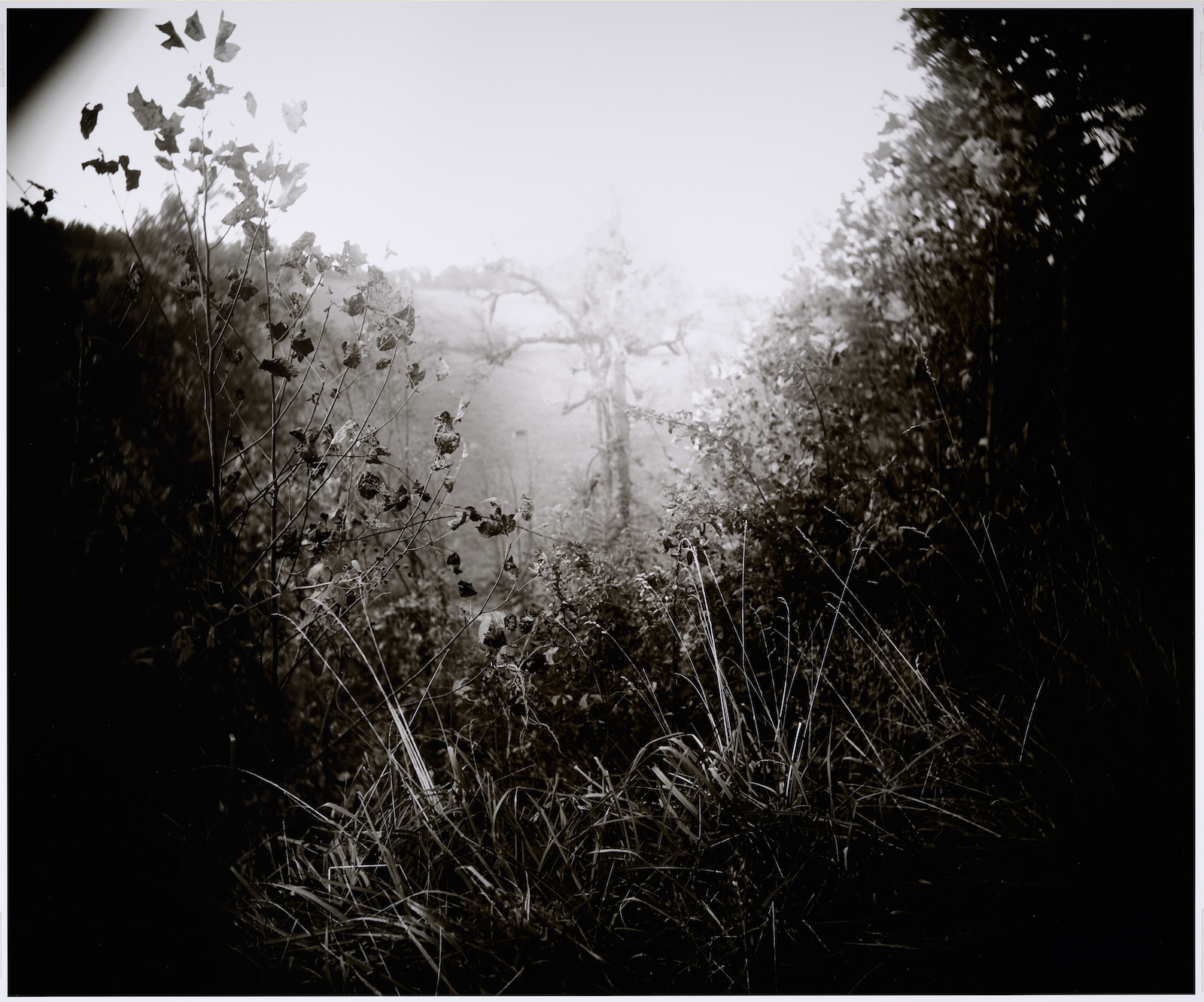

Jeff Whetstone combines his interest in nature and ecology with other influences, ranging from nineteenth-century landscape photography to the outdoor scenes of Northern Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder, to examine how land and culture are inextricably linked. The series Batture Ritual explores the micro- and macro-economies that have arisen along the batture near New Orleans.

The batture is an ephemeral strip of land, formed by gradually accumulating sediment, between the Mississippi River and the levee. From the French word battre, “to beat or strike,” the batture is the site where the water “beats” against the land. It is along this site that two vastly different economies coexist. Large commercial vessels traverse the river, while local fishers—many from Vietnamese immigrant families—cast their lines into the same water. In the first photograph a woman wades into the water and we see the end product of her efforts in the second. This personal interaction with the river provides a contrast to the literal flow of capitalism as shipping companies use the river to funnel goods to world markets. However different the means, the two groups of people—the cargo shippers and crews as much as the local fishers—are bound together in their dependence on the river.

This essay appears in the Winter 2018 issue (vol. 24, no. 4).

Melissa Gwynn is curatorial assistant at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. She received an MA in art history from Hunter College, New York.

People Get Ready: Southern Lens was organized by Melissa Gwynn, curatorial assistant at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. The exhibition was on view at the Nasher from September 1, 2018–January 6, 2019. The installation drew from the museum’s rapidly growing photography collection and featured several recent important acquisitions. Southern Lens was a complement to the exhibition People Get Ready: Building a Contemporary Collection, organized by Trevor Schoonmaker, Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs and Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher Curator of Contemporary Art.