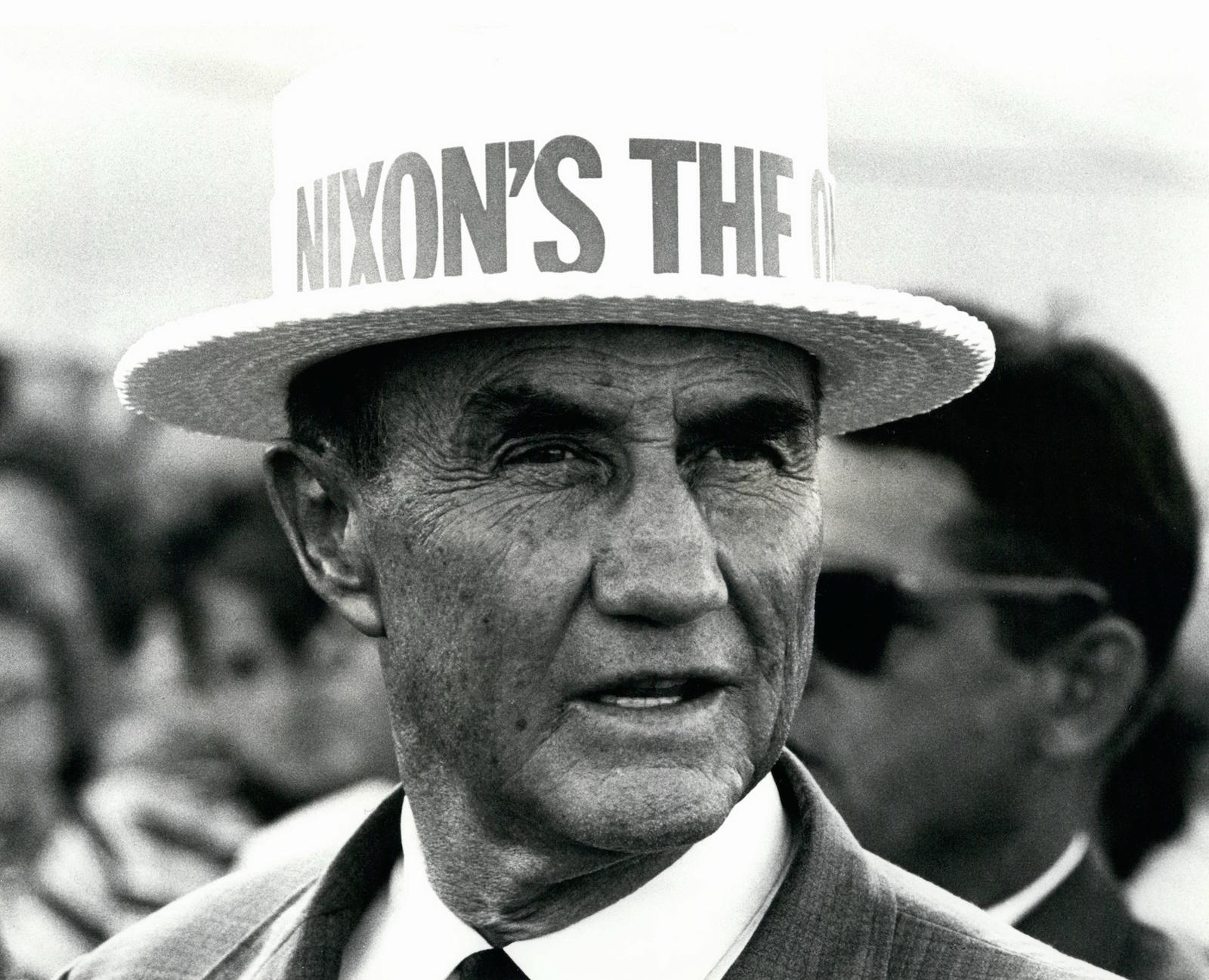

On August 14, 1970, Richard Nixon treated New Orleans, a city keen on parades, to a campaign-style motorcade. With Nixon standing and waving through the sunroof, his limousine moved slowly down wide Canal Street, then through narrow Chartres Street. Thousands of people lined the sidewalks to cheer and be near the President of the United States.

A photograph taken that day sits on a bookcase in my home office. The picture shows Nixon just outside the French Quarter hotel then known as the Royal Orleans. At the edge of the frame, there I am, standing on the sidewalk, hands in pants pockets, tan sport coat open. My assignment was to capture the sights, sounds, and “scene’’ of a presidential visit for the New Orleans States-Item, an afternoon newspaper, while more senior reporters covered the serious business of Nixon’s trip into the American South.

That business had to do with school desegregation. By court order, the period of “all deliberate speed,” as provided in the Brown ruling, was ending, and laggard southern districts had to desegregate when schools opened for the 1970–71 term. Nixon, who had served as vice president when President Dwight Eisenhower sent troops into Little Rock in 1957, met in New Orleans with the co-chairs of seven state advisory committees to tell them he wanted a peaceful opening of public schools.

In his 1991 book, One of Us: Richard Nixon and the American Dream, New York Times columnist Tom Wicker captures the political two-step that Nixon danced as he sought to govern and to carry out a strategy to turn the South into a Republican-dominated region as it had been a “solid Democratic South’’ for much of the twentieth century. Wicker gave Nixon credit for “a spectacular advance in desegregation’’ in 1970. “Perhaps the most significant achievement of his administration’s domestic actions,” Wicker wrote, came as “the Nixon administration had appeared in retreat from desegregation, while actively courting the white vote.”

Indeed, in his 1968 campaign and afterward, Nixon used coded language, political symbolism and court interventions as signals to southern white voters. In the aftermath of city riots in 1967 and 1968, as well as Vietnam War protests, Nixon said he was for “law and order.’’ His administration went to court to slow down school desegregation. Nixon tried to install two so-called strict-constructionist conservatives, Clement F. Haynesworth Jr. of South Carolina and G. Harrold Carswell of Florida, on the Supreme Court, but the Senate turned down both nominees.

By his political calculation to capitalize on the racial and cultural divisions of his day, Nixon opened the gate to the political polarization of the United States in 2018. While President Donald Trump hardly emulates the furtive and nuanced Nixon, there is a direct line that runs from the Nixonian “southern strategy’’ to the Trump presidency.

By his political calculation to capitalize on the racial and cultural divisions of his day, Nixon opened the gate to the political polarization of the United States in 2018.

Much punditry has been devoted to Trump’s victories in such Midwest states as Ohio, Wisconsin, and Michigan—significant, of course, to his winning the presidency. Still, 158 of Trump’s 304 electoral votes in 2018 came from 13 southern states, the former confederate states, plus West Virginia and Kentucky. The South now serves as the Republican Party’s essential base in American politics.

Flash back fifty years to the 1968 election, which featured a three-candidate presidential race that Nixon won with a modest plurality. In popular votes, Nixon finished with 43.4 percent (301 electoral votes), barely ahead of Democratic Vice President Hubert Humphrey at 42.7 percent (191 electoral votes), with Alabama segregationist George Wallace trailing at 13.5 percent (45 electoral votes). Wallace carried Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, while Humphrey carried Texas and West Virginia.

By signaling during the 1968 campaign that he would ease pressure on the South on racial issues, Nixon gained the support of South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond, who had become a Republican after running for president as a Dixiecrat in 1948. After the election, Thurmond’s chief political aide Harry Dent became a White House aide.

Also after the election, Nixon adviser Kevin P. Phillips published his influential book, The Emerging Republican Majority. Phillips long insisted that his book offered political data and trend analysis, not a strategy. Still, his analysis pointed the Nixonians toward capturing Wallace voters.

“Three quarters or more of the Wallace electorate represented lost Nixon votes,’’ Phillips wrote. He went on to suggest that “nothing more than an effective and responsibly conservative Nixon administration is necessary to bring most of the southern Wallace electorate into the fold against a northeastern liberal Democratic presidential nominee. Abandonment of civil rights enforcement would be self-defeating. Maintenance of Negro voting rights in Dixie, far from being contrary to GOP interests, is essential if southern conservatives are to be pressured into switching to the Republican Party—for Negroes are beginning to seize control of the national Democratic Party in some Black Belt areas.”

In their book, The Southern Strategy, published shortly after the 1970 mid-term elections, Atlanta journalists Reg Murphy and Hal Gulliver wrote a detailed—and critical—account of the strategy in practice. “It was a cynical strategy, this catering in subtle ways to the segregationist leanings of white Southern voters,’’ Murphy and Gulliver wrote, “yet pretending with high rhetoric that the real aim was simply to treat the South fairly, to let it become part of the nation again.”

White voters got the message. Along the New Orleans motorcade route, a Nixon supporter held up a hand-lettered sign that read, “I am for Nixon . . . Less Federal Control. Equal Treatment for the South.”

In rhetoric and disposition, Trump comes across as more akin to Wallace than Nixon. Show undergraduates a video of Wallace’s caustic 1963 inaugural address, as I have, and they immediately say he sounds like Trump.

Still, Trump sends out Southern Strategy–type signals. Without proof, he spent months asserting that President Barack Obama was not U.S.-born. He has assailed professional football players for “taking a knee’’ as a protest of white police violence against young black men. He has attempted to stanch immigration from Mexico and Central America, even to the point of separating children and parents.

Watergate cut short Nixon’s presidency and deprived him of more time to woo the South. Democrat Jimmy Carter of Georgia won the presidency in 1976, and “New South’’ governors won elections across the region as the two major parties reconfigured post–Voting Rights Act.

Show undergraduates a video of Wallace’s caustic 1963 inaugural address, as I have, and they immediately say he sounds like Trump.

In the 1980 campaign, and in his two-terms in the White House, Ronald Reagan picked up the pursuit of switching white southern voters to the Republican Party. Reagan also elevated white evangelical Christians, previously absent from electoral politics, to a key element of the GOP coalition. Republican-appointed judges released southern states and localities from school desegregation and voting rights mandates—and now resegregation of schools has taken hold in the South as well as in the nation. Republicans, led by the combative Newt Gingrich of Georgia, won a U.S. House majority in 1994 and intensified congressional divisiveness. The Republicans’ center of gravity shifted farther to the right with the rise of the Tea Party faction following the election of Democrat Barack Obama in 2008.

By the time New Yorker Donald Trump won the party’s presidential nomination in 2016, Republicans held almost every governor’s office and controlled most legislatures across the South. In capturing the GOP nomination, he defeated Jeb Bush of Florida, Ted Cruz of Texas, and Lindsay Graham of South Carolina. Not even powerful southerners could hold back the big-city builder and reality-show celebrity from dominating— and reshaping—a national party rooted in a fifty-year regional strategy.