The art works represented here are housed in the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. William Arnett, the Foundation’s founder, assembled the collection over a thirty-year period, during which he travelled throughout the South and interviewed the artists. Arnett selected the artworks illustrated here, offering a commentary on each one in a recorded conversation in 2013. In the same year, he made arrangements for housing the Souls Grown Deep Archive in the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Water always finds a way,” a carpenter once explained, evaluating years of roof damage concealed behind a failed soffit. The same holds true for the presence of water as a recurring motif in the art of the American South. Work by Thornton Dial, Georgia Speller, Lonnie Holley, Ronald Lockett, Joe Minter, Thornton Dial Jr., Purvis Young, Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Joe Light, and Ralph Griffin offers multiple perspectives on water as a powerful metaphor speaking to deep histories of African American experience in the South. In their work, water finds a way in the description and critique of power. The images represented in this portfolio reveal some of that coded metaphorical flow.

The conflicted, sometimes paradoxical, representations of water in these works address water as barrier and avenue, as threatened, as a shaper of historical identities. Something to be crossed; something that resists crossing. Something that gives life; something that can be poisoned and deadly. Water is the promise on the other side of River Jordan; it is the deadly highway and misery of the Middle Passage. Water is defined by too much (flood) and too little (drought). Water is allegorical, metaphorical, and historical. It is about regulation and resistance.

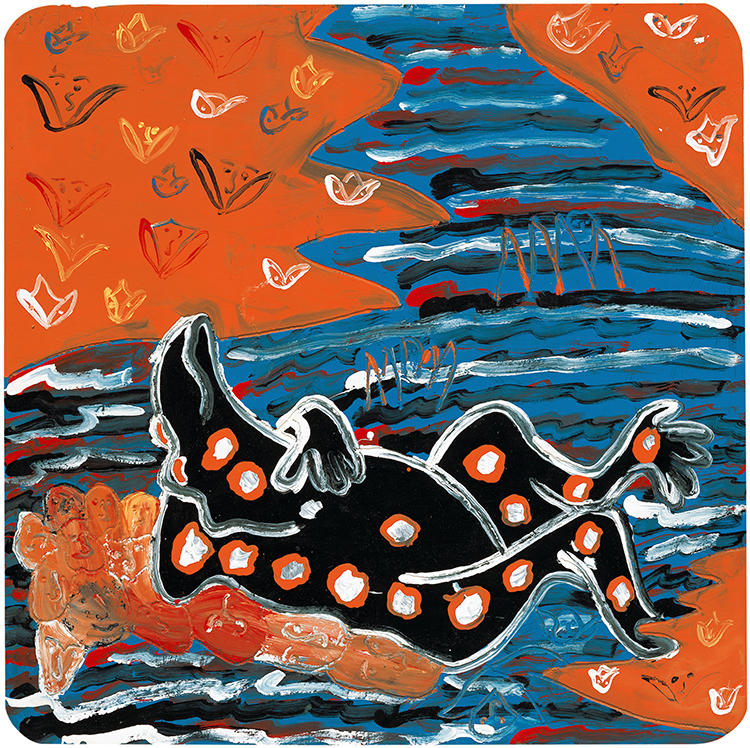

William Arnett explains, “There is Joe Light with his hobo, which is his alter ego, looking for enlightenment. Joe Light did four of these, each one a different color. One is black, one is brown, one is red, and one is white. He is showing his own racial makeup, and also the racial makeup of the people in his class, which is part black, part white, part Native American.” Although autobiographical on the surface, Light’s work speaks to larger histories of race and the quest for understanding: “The water is the separation again from every man walking along trying to find enlightenment and the enlightened phase of civilization, which is represented here by mountains separated by a river. Light shows us nature in terms of a mountain and a river and grass growing. He carries on his back a knapsack.” Balanced on a branch near the shouldered pole “a bird is waiting to sit on his head.” The bird atop the head, what Light termed the birdman, is “the symbol he uses to describe the opposite of the hobo or the unenlightened person. That idea came to him when he was in prison as a teenager and he had been studying the Old Testament with a chaplain. [H]e decided he was, deep down, a Hebrew, because the Old Testament made more sense to him than the New Testament, so he called himself a convert to ‘the Hebrew religion.’ On occasion, he thinks he had a bird fly into his cell and light on his head. And so, that became the moment of his enlightenment, which he then represented in art.” The river on The Incredible Hobo can also be read as the River Jordan in the sense that “the River Jordan has to be crossed, symbolizing that something different lies on the other side from where you are.” Although enlightenment and self-realization reside on a distant shore, they can be attained.

Thompson Bridge can be read on one level as a memory painting depicting a sentimentally recollected scene from Sudduth’s life. On another level, though, it connects the representation of water that acts as a barrier to water that can be spanned or crossed. “Thompson Bridge,” Arnett notes, “was an actual covered bridge and seemed to have had some special meaning to the people in Sudduth’s community.” The specificity of that meaning is lost to us, but what remains is the representation of two young girls fishing on the viewer’s side of the river while Sudduth, rifle to shoulder, stalks his quarry across the stream. Arnett notes that Sudduth’s painting operates provocatively in conversations about power and identity shared in the works of other artists illustrated here. The river, a deeply nuanced metaphor, signifies border and threshold. To cross the river constitutes an act of courage, strength, will, and deliverance. In its waters, sins are washed away and impediments overcome; on the distant shore lie salvation and freedom.

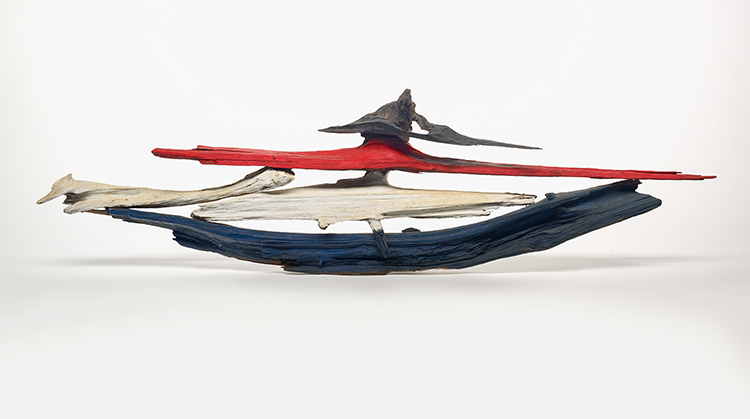

Irony, signifying, and political critique operate at the heart of Griffin’s work. Griffin “lived down near a lot of water and found many . . . distressed pieces of wood that have been worked by the water. In a noteworthy piece called Noah’s Ark, he painted the water-worn wood red, white, and blue. As with most of the black artists [in the Souls Grown Deep Foundation collection] who do things that seem to be patriotic or about America, the art is really about something else: black life in America. The work is not always as ‘patriotic’ as it might appear to be.”

In this diptych, Georgia Speller shows two landscapes: “On the left is one of the big tourist riverboats and on the right is a gentrified house up on the hill. Those are like two components of white culture or gentrified civilization that she is excluded from . . . The water is where the riverboat goes. But, as her husband Henry Speller said to me once, the only time black folks are able to do something with the river is when they’re working on the levee loading and unloading things and even walking out into the water to put things on and off boats. It’s almost like a white swimming pool. They’re not allowed in it unless they’re working.” The same holds true for life in and around the big house on the hill.

“The deer was an autobiographical alter ego for Lockett. He grew up two doors from Thornton Dial, who was his role model and mentor and person who he probably loved and respected most in the world. Where Dial had the tiger as his alter ego, which was fierce and struggling, and you couldn’t stop it, Lockett chose the deer, often showing it entrapped, netted, or in flight. In Drought you have the deer not tied down or fenced in; the deer is out on his own—but there is no water, as in drought. He’s looking to find water, and he’s poking his face along the ground, but he hasn’t found any water yet.” Drought focuses on the life-giving aspect of water and desperation in its absence. Lockett presents us with another dimension of southern water marked not by catastrophic flood and cyclonic calamity, but by a long, drawn out absence of recognition, respect, opportunity.

In another reference to water, Lockett speaks to loss through pollution, “The things that are in the river floating—dead birds, dead fish, dead trees—also serve as surrogate deer to metaphorically depict the young black man in the white world of Lockett’s youth, struggling to survive.” Lockett connects the fragility of the natural environment assaulted through mindless human action and the precarious futures of young African American men like himself who not only find themselves challenged in the navigation and crossing of the social waters around them but also imperiled by the toxic ruination of those waters by unseen hands.

Dial represents “the president as a frog lying on a rock in the middle of the water, sleeping while little children are dying and their ghosts are floating around in the background. The president and his staff are depicted as a frog and a bunch of rocks doing nothing.” This work offers a pointed counterpoint to Georgia Speller’s painting where access is denied, suggesting that those with access (power) often do nothing through simple indifference to the needs of others—an indictment that finds its expression of the art of Joe Minter, Thornton Dial, and Ronald Lockett.

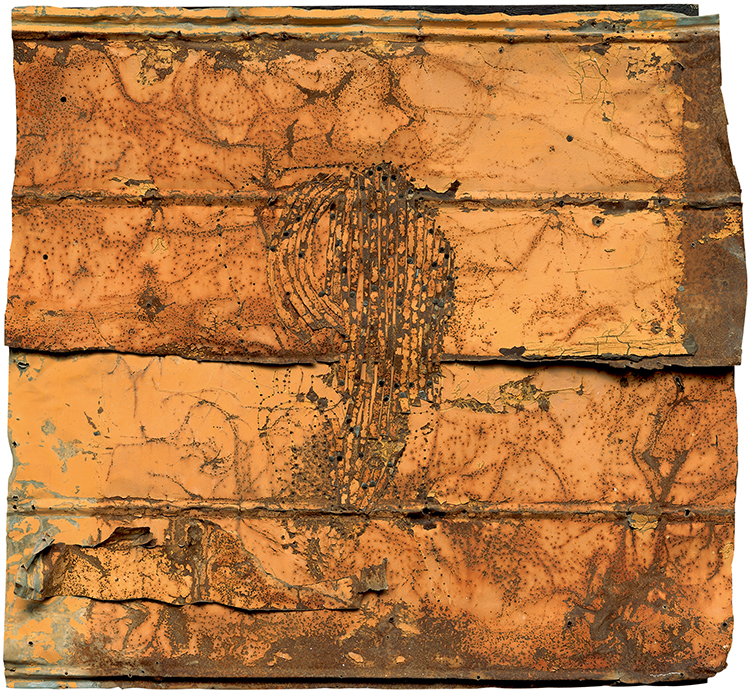

Thornton Dial created a series of disaster works in 2011 that included meditations on the droughts in Texas, the Tuscaloosa tornado outbreak, Hurricane Katrina, and the Japanese tsunami. “Ninth Ward visualizes the Katrina disaster in New Orleans,” marked by “catastrophic water and the ravages of nature, but there’s some hint at redemption in the piece. He did the Ninth Ward and even before that he did Tuscaloosa, which depicted the tornado that went through Tuscaloosa and also went through Dial’s yard. It went right on past Dial’s house when they were in it. In both of these pieces . . . even though there is everything from torn-down houses to dead babies, there is also something that indicates that it will be overcome.” Arnett observes that in Dial’s art resurrection and the cycle of life inevitably triumph in the aftermath of disaster.

This excerpt first appeared in the Southern Waters Issue (Vol. 20, No. 3: Fall 2014). Read the full essay at Project MUSE.

Bernard L. Herman is the George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of American Studies and Folklore at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. His books include Thornton Dial: Thoughts on Paper (2011), Town House: Architecture and Material Life in the Early American City, 1780–1830 (2005), and The Stolen House (1992). He has published essays, lectured, and offered courses on visual and material culture, architectural history, self-taught and vernacular art, foodways, culture-based economic development, and seventeenth-and eighteenth-century material life.