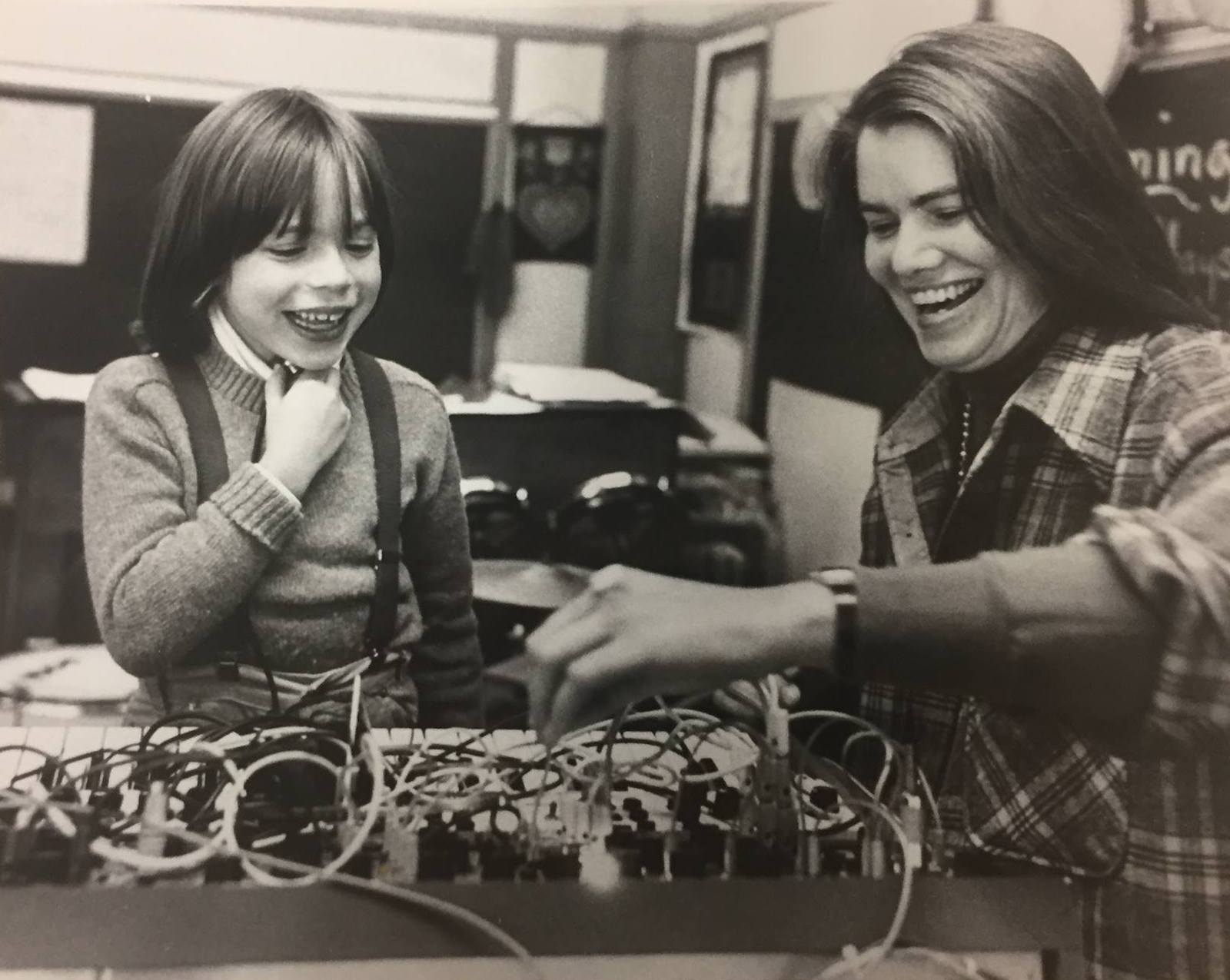

In the mid-1970s, Sorrell Hays, a composer of electronic music, took her synthesizers, sound equipment, and contact mics to Dougherty County, Georgia. She was there to introduce children in newly desegregated classrooms to experimental forms of music-making. For Hays (1941–2020), it was a return to the South after almost two decades away and a confrontation with a changed region from that of her upbringing in the 1940s and 1950s. Born in Tennessee, Hays grew up surrounded by music. As a child she played the piano in church and was deeply influenced by hymns and other forms of southern sound. She trained in classical piano in Europe, Madison, Wisconsin, and New York, eventually becoming an internationally known concert pianist. By the 1970s, she was part of a network of women composing electronic music and, later, opera. Throughout her life, Hays defied expectations and created a path at once southern and global.

In 2016 and 2017, along with Hannah Givens, we interviewed Hays at Swallow Hollow, her home in rural Haralson County, Georgia. She shared the former fish camp with her wife Marilyn Ries. The two had spent decades in New York City in the heartbeat of its experimental music scene but returned to the rural South full-time in the 2000s. They were the first same-sex couple married in Haralson County after the 2015 SCOTUS ruling legalized gay marriage (they married on August 6, the date of their shared birthday). Our interview was part of an LGBTQ+ oral history project for the Center for Public History at the University of West Georgia, an initiative that documented the lives and experiences of queer-identified southerners who made the west Georgia region home (all of us were staff members of the Center as graduate students or faculty). Two interview sessions captured Hays’s musical and political development, which evolved in tandem. Sorrel understood we would transcribe, archive, and make the interview available for research. She articulated her legacy on her own terms, and, despite the oral history initiative, she declined an exploration of how her sexual identity might have influenced her work. She never hid her personal life and was active in LGBTQ+ networks in west Georgia, yet, once the recorder was on, she gracefully deflected questions about queerness. But not difference. We present here the self she fashioned in our interviews. We have chosen clips from Hays’s reflections on her southern musical influences and projects that offered electronic music and freeform performance to a changing South in the 1970s.1

Sorrel Hays was born in 1941 to a family on the move, like many in the mid-1940s. The family settled in Chattanooga, Tennessee, when Hays was four, her father a manager of “soft” foods businesses. Her parents had grown up in rural Arkansas, which invested the family with a sense of home, even with a peripatetic lifestyle, and provided the undercurrents for the deep musical traditions that shaped Hays’s later work as a composer.

Because my father ran the general store, he could do things like order band instruments, so he bought band instruments for the local high school. And though he had no musical training, he played the drums. At this time in Arkansas, in the small towns—this is the late teens and the ’20s of the last century—making music at home was one of the chief entertainments. So he knew music-making. His mother played the organ, and she played the guitar and she fully enjoyed life. She ordered her liquor from St. Louis, her player piano from Sears and Roebuck. My [Aunt] Veda, and [I] had another aunt whom I adored, Veera, both sang and played a little bit, and on my mother’s side, everybody in the family made music. But mother played by ear, her older sister Ella Mae played the piano quite well . . . played pop songs and I have sheet music from those years, “Twelfth Street Rag” and things like that. And another aunt, Alberta, was a good singer. She had a lovely voice. So, music-making was natural. And as we were growing up, my two brothers and I, having music lessons was a normal part of life. It’s what we were expected to do was to learn at least a little music. My two brothers stopped lessons after a year or two; they took clarinet lessons. But with me, it just took.

Hays inherited a gift for sight-reading and musicality. The places in which southerners performed music in the mid twentieth century—in homes, in communal settings, in churches—gave her an understanding of sound as a shared experience. She compared southerners’ former access to musical spaces to the present day. Concerts and performances take place on university campuses, she argued, which are often removed from the communities they inhabit.

[A] lot of my background came from what I’ll call community music-making; it’s not talked about as much that way anymore, because we don’t do as much of it. But remember, only fifty years ago, music clubs kept alive the art music of this country. Now, it happens another way, usually through universities.

The church was central to Hays’s development of harmonic structure. She came of age in the Methodist Church, where her grandfather served as a minister and hymn writer. The church afforded an opportunity to learn piano and organ and to perform for public audiences.

The hymnody . . . of course, I grew up in the Methodist Church and played organ and piano when I was quite young. And I remember my first funeral. [The] first funeral I ever went to I played the organ at, which was a revelation. But Chattanooga was, and I think still is, a very church-dominated city. And so, at every turn, we had hymns . . . and the 1-4-5-1 harmony has stuck with me. I happen to like it, although I prefer to configure it a little bit more adventuresomely.

Hays grew up in the segregated South, but like other young white people, she consumed and was influenced by African American music. She sought out performances by Black artists and, in a segment where she remembers, uncomfortably, the South’s racial terminology (and attempts to distance herself from it), she described Black music as being both concentrated (in performances, on the radio) and suffused throughout the southern soundscape.

And I remember also going to a concert at Memorial Auditorium in Chattanooga, which had been built after World War I and was huge. [It] had community concerts, had wrestling matches, and also had what we called “Black concerts.” At that time, maybe “Negro concerts,” I don’t remember. And whites could only sit up in the very highest balcony. Now, this place held 5,000 people. And it was all, at the time it would have been called a “colored” audience, except for this balcony of whites, and I went and I remember the power of the music. But I also heard blues on radio and just in the air, in the air.

At age twelve, she began teaching piano to younger children and became the student of Harold Cadek, whose family had begun the Cadek Conservatory of Music in Chattanooga in 1904. After high school, Hays found work in 1959 accompanying the Chattanooga Boys Choir as an assistant conductor. She credited her later work in opera to time with the Boys Choir, which cemented her love of the human voice. That love would move her to collect southern voices in the late 1970s.2

I’ve never been an orchestral conductor and became less so as time went along, the more I gave solo concerts. But I’ve always enjoyed the human voice. And those early years with my family, singing, and then with the opera singers I accompanied, and the Boys Choir, they all led me towards what I eventually started doing as a composer. And my love for the human voice has kept me at it, even though writing opera is one of the most difficult things to fulfill, that one can imagine as a composer, because it’s such a production to produce [laughs].

Hays’s early musical life unfolded in segregated spaces—the white church, the conservatory, the Boys Choir. At her own admission, she was “naive” when she left the South in 1963 to pursue musical training in Munich, Germany, thanks to a Maclellan Foundation Scholarship. She encountered in postwar Germany new ideas and new forms of music and, like many expatriate southerners, cast eyes back to the South with a fresh perspective. In the context of Cold War Germany, and because of encounters with Black opera singers who could not perform in the US, Hays’s “politics really began” in this period.3

Three quarters, no three-fifths of the student body at the Hochschule [für Musik, in Munich] were foreigners, because Germany tried very hard, from the ’50s onward, to bring international people in. They were trying so hard to overcome that burden of what had happened in World War II. So they sent many people my age or a little older, perhaps, to the United States (I met them later), and they were so friendly to Americans, they understood. And then they gave scholarships to many Americans to further their education and, in fact, many professional opportunities. Many of our opera singers, particularly the African American opera singers, in that period, in the late ’50s and ’60s, went to Germany because they could be hired. And they could not get jobs in this country. You know, our opera stages did not open up to, and even our orchestras, to African Americans until, actually, the late ’80s and ’90s. That’s a long time.

I became involved in the differences that Germany was experiencing between East Germany and West Germany, heard a lot of the music of Bertold Brecht, began to explore those political bents. And so that’s where my politics really began, in Germany.

It was quite a wrench, leaving a town like Chattanooga and coming to a cosmopolitan city like Munich. I had had no political involvement in the States. And I began to understand how one could be politically involved. One of my friends in Munich, a next-door neighbor, enlightened me. I just . . . he had been involved and he said—he was nineteen at the time—and he said, “When I’m twenty-eight, I’ll probably give all this up,” as many students do. You know, heavily involved in college, and then you get to another part of your life and you drop it. But I became involved in the differences that Germany was experiencing between East Germany and West Germany, heard a lot of the music of Bertold Brecht, began to explore those political bents. And so that’s where my politics really began, in Germany.

Hays returned to the South in 1966 but would not remain long. She had earned a Diplom Meisterklasse at the Hochschule für Musik in Munich and decided to continue her schooling at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with Paul Badura-Skoda. After earning a master’s degree in music there, she moved to New York City in 1970. In her thirties, Hays’s career as an award-winning concert pianist began. Hays toured Europe extensively in the early 1970s, thanks to robust state-supported arts programs. It was during this period, too, that she left behind a traditional classical repertoire in favor of atonal and twentieth-century composers.

So I went to Europe then in ’71, won the [Gaudeamus] Competition for Interpreters of New Music, which is the direction I had started taking in Madison, [which was a] divergence from my past, musically, because I embraced twentieth-century music. It’s really what saved the piano for me because I grew to not loathe, exactly, though I’ve never been fond of Beethoven, but just could not bear sometimes to hear this standard classical repertoire. So I found, in Henry Cowell and John Cage and Morton Feldman and a number of the European composers, the path I wanted to follow as a pianist. And that eventually helped me find my way as a composer. And from ’71 on was the advent of my professional life as a concert pianist. And I was back to Europe because there the subsidized art scene allowed me to earn quite a bit of money in radio stations and concert halls that were only open in this country on university campuses. And at that time, in the ’70s, particularly in the early ’80s, there were not faculties who employed people who focused on new music. So they had some little budgets to bring me and other people to campus as guest artists, and so I did that around the country.

Hays began experimenting with electronic music after acquiring a reel-to-reel tape recorder in the mid-1960s. Curious about sonics—“the odd parts of musical sound that we don’t think are music”—she found herself exploring a new genre.

How did I get into it? That’s a good question. Because I started playing around with sonics, you know, the odd parts of musical sound that we often don’t think are music, but they have become music. And it was a time [in] the ’60s and ’70s when so much was happening with video with tape recorders, tape recording music. And I was playing around with tape recorders in Europe. I had received a lump sum at the end of my last year in Munich, as a recipient of the Bavarian scholarship, they had a little windfall, and I spent it on a microphone and tape recorder. And I like to play around with the tape recorder.

In the 1970s, Hays began creating music in a mode most often associated with male composers, such as John Cage and Terry Riley. But as Martha Mockus, a scholar of composer Pauline Oliveros, argued, queer women and feminists were fundamental to this new scene and often supported and inspired each other. Sorrel Hays felt keenly the lack of recognition of women composers of new music and worked in notable ways to create more visibility for women. She became active in the International League of Women Composers and, in 1976, organized a series of concerts by women composers for the New School. Hays remembered being “part of the whole movement of women” of the 1970s.4

And many of the male composers that I encountered were simply unaware that we felt this way, they simply couldn’t understand, really, what are we complaining about? So it took a lot of pressure and a lot of showing of statistics: how many women have been funded by the NEA? How many women are on the board for awards for ASCAP [American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers]? Each area, you know, simple things. They seem to me obvious. For example, the Rockefeller Foundation had a competition—and this was a high-powered competition—for performers of new music. And [in] these competitions, you have free choice and then you have required compositions you have to perform. And there was not a single female composer on the list. So I wrote to them, pointed it out, and gave them a list of composers. And so the next time they had, I believe, one, and the next time they had two; it was movement. I mean, each time something came up, I tried to address it, and the League of Women Composers did this by having concerts. Now, I had, in ‘76, produced a series of concert lectures at the New School. People could get credit, but it was really a concert series. And we had two composers per evening . . . I think we had maybe twelve sessions. And then the audience could address the composers after the works were performed and had some wonderful performances in that series.

Hays’s compositions were sonic manifestations of her political commitments in this era.

Hays’s compositions were sonic manifestations of her political commitments in this era—Celebration of No, composed in the early 1980s, for example, featured women saying “no” in twenty languages. In the 1980s, she joined feminist peace encampments at nuclear production sites in New York and in England, documenting the camps with her partner Marilyn, who was a sound engineer. Together, they produced a film about these experiences, CD: The Ritual of Civil Disobedience.5

In the mid-1970s, she returned again to the South, thanks to a program proposed by President Richard Nixon and funded by Congress in 1970. The Emergency School Aid Act supported school desegregation efforts across the country. Some of the monies were earmarked for arts programs and funneled from the National Endowment for the Arts to state agencies to “lessen desegregation tensions through arts programs.” The Georgia Council for the Arts, one of only eleven grantees in the program’s inaugural year, sent visiting artists to school systems in the state that had a desegregation plan in place, including those in Fulton, Bibb, Butts, Thomas, and Dougherty Counties. Hays served in the latter at Albany High School. Dancer Barbara Sullivan (founder of the Atlanta Dance Theater), photographer Charles A. Leonard, filmmaker Ngaio Killingsworth, and improvisational actor Charles Helms also joined the Georgia program. During her time in Albany, Hays taught electronic music at the high schools and toured her synthesizer to all of the elementary schools in Dougherty County. She used sound as a way to invite children to explore the texture of their own voices.6

And I had a piece of equipment that allowed a microphone, a contact mic, to be put on the throat and then it went into the synthesizer and as you spoke, of course, it made all sorts of weird sounds, and they loved that. I used that a lot. It was a very good meeter-and-greeter.

In the midst of desegregation in a place that was, in her words, “rigid and deeply entrenched” in bigotry, Hays brought multi-racial students together to co-create sonics as part of her Sensevents piece, which she performed at the Banks Haley Gallery in Albany. Hays described the piece to the Atlanta Constitution in 1976 as “a simultaneous activity of light sequences coordinated with patterns in electronic music. And you, the audience, make things up. You hit the foot switches, a sculpture lights up and begins to move, and the musicians and dancers receive their cues to play and move. It is the audience flow that determines the occurrences and duration of the music.”7

And then we also did a version of Sensevents in the Banks Haley Museum there, and they bussed in something like 600 kids over the course of a day . . . This was a piece with switch mats on the floor that activated lights and electronics and musicians to play. So the children loved it, of course, and so they tromped through.

In February 1975, Hays performed the piece again at Lenox Square Mall in Atlanta with dancers Barbara Sullivan and Charly Helms, who were also a part of the Georgia Council for the Arts artist residency program. Again, the primary audience was children.8

Each of the six performers had their own score, tempo, and they were queued to play by moving sculptures, which I had built of Styrofoam and armature and simple motors, or light patterns, which were on a computerized system. All of this mechanism turned on by footswitches. And I think I told the story about the kiddies in Atlanta, [at] Lenox Square Mall . . . finding out if they sat on these foot switches, everything would keep happening. They wanted to watch the sculptures go up, up and down, and the lights blink, and we had a lot of fun with that piece.

It was this pedagogical work with southern children that led Hays to begin fieldwork in the South. She cites her time in Albany, Georgia, as the inspiration behind her Southern Voices orchestral composition, commissioned by the Chattanooga Symphony for its 50th anniversary in 1984. Her work on the piece, however, began in the late 1970s when she traveled through the South to record southern voices, first with her Aunt Veda and then with filmmaker George Stoney. She toted a reel-to-reel portable Uher recorder across the South, to Arkansas, Tennessee, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Hays approached people on the street and asked two questions: “Where were you born?” and “What makes you happy”? She recorded their answers and subsequent conversation, as well as the traditional music she encountered in her travels. She hoped to capture what she called southern “speech melody”—intonation, accent, and phrasing.

And I adore the southern [manner of speech.] There is a languor . . . I don’t think of it as a rhythm so much as a—well, in musical terms, when you have a phrase, you put a slur over a number of notes, and they’re connected. And that kind of connection seems to flow through southern speech. And sometimes I’ll just sit and listen to people and hear what they do with their beginnings and ends and see how they contour that speech. And I’m not paying attention to the meaning of what they’re saying. It’s just I adore that texture of language. And that was what I was after in Southern Voices.

What I was going after, what at first was the rhythm of the speech, and the pitch modulation, up and down, to try to get at what I call the speech melody. And so I had to actually try it; it was fairly primitive equipment at that time. The synthesizer I was using was a Buchla and it could do part of that. And so I used the part I could. It would also add sometimes some things that didn’t quite belong as a part of that. I couldn’t filter it all out, but I could program pretty well to get rid of them and get an approximation of the speech melody.

After gathering interviews, Hays began “abstracting the speech into musical terms” by running the tape reels through a synthesizer. In its premier in Chattanooga, Southern Voices featured award-winning soprano Daisy Newman, a southern-born Black artist who shared Hays’s sonic sensibility. Both women inflected the lyrics with early- and mid-twentieth-century southern musical influences.

So after I [recorded that speech] and began listening, I was abstracting the speech into musical terms. After I did that—sometimes I had to go back to the original again and again—I would notate it. So I have, or did, somewhere I have notebooks full of these bits and pieces of speech put into musical terms, you know, just musical notation. And that’s what I had to do is set up, you know, hundreds of these, to then try to get a fabric for orchestral players to play that made some sort of musical sense. And I used a mixture of counterpoint of melodies, which I liked very much, because it set the rhythms against each other, like a babble of the voices. And then interjecting hymn-like sections. And since it was the voice, I added soprano to the orchestra. And [Daisy Newman] gave, I think, the continuity to the instrumental speech in her human voice.

Hays brought her political commitments as a feminist to Southern Voices, describing the project as an attempt to communicate the tension in loving and being repelled by the South.

But the lyrics—you know, I was getting my own jabs in because I’ve had my differences with Chattanooga [laughs]—go like this, “We’re a little bit set in our ways. The South, the South” . . . there are other little bits about the difficulties of being in the South, and that conflicting emotion that I think all of us who have moved out of the South and come back have of the love for the land, the people, the language, and enormous differences about its intransigence about so many things, which do divide us. And so, within the text of Southern Voices, and also musically, I was thinking that way, too, I love this place and I understand a lot about it. But then, why are you so what you are?

Hays was more forthright in Southern Voices: A Composer’s Exploration, the documentary she produced in 1985 with George Stoney: “One can’t put everything into one piece of music. Southern Voices for orchestra is, however, the first large exposition of a sometimes muddy stew of my love and my hate for my native region. How can I be so drawn to so much of what is the South, and yet unable to remain for long? . . . Because of the counter side of beauty, of friendliness and courtesy and hospitality and grace and strong moral sense. The counter side being intolerance, racial discrimination, sexual oppression, and paternalism of a kind sometimes so subtle that even I, and many women in the South, often fail to see its condescending face before we’ve been taken in by it.”9

It was through experimental music that she offered southerners a way to hear and see themselves in a new light.

Hays’s escape from the South, her remarkable education in Europe and in the northern United States, and her inventive and experimental compositions allowed her to return to the South, even with a “muddy stew” of emotions about the region. It was through experimental music that she offered southerners a way to hear and see themselves in a new light—allowing children, for instance, to experiment with the volume, intonation, and texture of their own voices. In Southern Voices, she abstracted southern speech and, in doing so, provided both a celebration of and a critical commentary on the South’s rooted traditions. It was never her aim to simplify and celebrate the South; in the documentary Southern Voices, she recognized that “the babble of voices aren’t always pleasant.”

In the 1980s, Hays and Ries bought Swallow Hollow in Haralson County as a kind of retreat and creative space. Hays’s work transitioned to opera productions in the 1990s and 2000s; her last production was The Bee Opera in Ljublijana, Slovenia, in 2017, the same year that her wife Marilyn died. Hays was working on a new opera, Bella, about the life of Bella Abzug, when she passed away in February 2020, at age 78.

A friend asked me, he said, “You’re doing opera? That’s very old fashioned,” because he knew me as doing the earlier experimental thing. I said, “I like to write opera. You know, I enjoy it, Michael” [laughs]. He said, “Nobody does that anymore.” I said, “I do.” Yes, the tension is a necessity. Why do you keep producing new work unless there is something going on inside that you want to get out?

Jennifer Sutton is an oral historian currently working in Ingram Library at the University of West Georgia. She received an M.A. in Public History from UWG.

Julia Brock is currently assistant professor of History and coordinator of the Public History Concentration at the University of Alabama. Prior to UA, she co-directed the Center for Public History at the University of West Georgia.

Header image: Andrew Paterson / Alamy Stock Photo

- All audio is courtesy of Center for Public History, University of West Georgia. For an overview of Sorrel Hays’s work to 1995, see “Hays, Sorrel (Doris Ernestine),” Norton Grove Dictionary of Women Composers, Julie Anne Sadie and Rhian Samuel, eds. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995), 213–215. For a succinct biography, see an obituary written by Loretta Goldberg, “Sorrel Hays: In Memoriam,” Loretta Goldberg, February 18, 2020, https://lorettagoldberg.com/sorrel-hays-in-memoriam/. Hays was born Doris Ernestine Hays but changed her name to Sorrel (her grandmother’s name) in 1985.

- For more on the Cadek family and conservatory, see Donald Clyde Runyan, “The Influence of Joseph O. Cadek and his Family on the Music Life of Chattanooga, Tennessee (1893–1973),” PhD dissertation, Peabody College for Teachers at Vanderbilt University, 1980.

- Goldberg, “Sorrel Hays: In Memoriam.”

- Martha Mockus, Sounding Out: Pauline Oliveros and Lesbian Musicality (New York: Routledge, 2007), 2.

- Hays and Ries gave interviews about their work to the Peace Encampment Herstory Project; see “Herstory 061 and 062, Sorrel Hays and Marilyn Ries,” Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice, February 4, 2015, http://peacecampherstory.blogspot.com/2015/02/herstory-061-062-sorrel-hays-marilyn.html.

- See Richard Nixon, “Special Message to Congress Proposing the Emergency School Aid Act of 1970,” May 21, 1970, The American Presidency Project, University of California Santa Barbara, accessed February 21, 2020, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-proposing-the-emergency-school-aid-act-1970. Nixon’s approach to desegregation was severely criticized by supporters of the Civil Rights Movement and desegregation at the time; at his proposal of the Emergency School Aid Act, Senator Walter Mondale (D-Minn.) charged that Nixon sought to “substitute $500 million of diverted federal funds for moral leadership it has abandoned.” Quoted in Gareth Davies, “Richard Nixon and the Desegregation of Southern Schools,” Journal of Policy History 19, no. 4 (2007): 387. Davis also provides a helpful overview of historians’ debates about Nixon’s legacy regarding desegregation; Helen C. Smith, “More than the Three R’s: Georgia Students are Learning Dance, Art, and Drama Under a New Program,” Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1975; “Appointment of Artists Announced,” Atlanta Constitution, October 5, 1975.

- Helen C. Smith, “She Creates Art Forms with Sight, Sound,” Atlanta Constitution, January 10, 1976.

- Smith, “She Creates Art Forms,” January 10, 1976.

- Sorrel Doris Hays and George C. Stoney, Southern Voices: A Composer’s Exploration, with Sorrel Doris Hays (Watertown, MA.: Documentary Educational Resources, 1985), film.