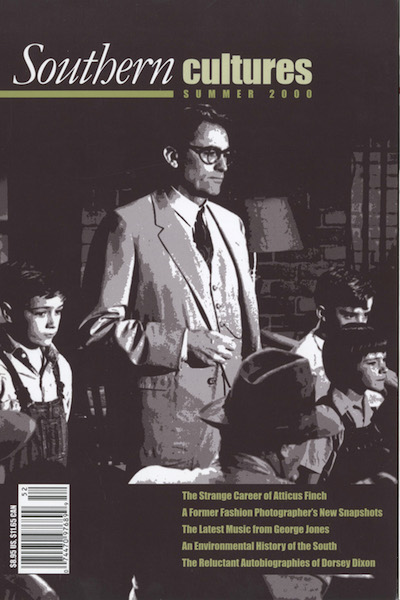

Contemporary debates concerning race in America owe much to the 1960s when African Americans and other minority groups gained basic legal protections and rights of citizenship denied them in the century following Reconstruction. The current offspring of this movement is multiculturalism, a term that encompasses a range of progressive educational techniques, policy recommendations, and social movements that celebrate racial and ethnic differences and seek to empower people to pursue goals of personal and communal freedom. One of the basic questions raised in the 1960s that reverberates in multiculturalism today is who in our society is allowed to speak authoritatively on racial issues. Over the course of the twentieth century, but particularly with the flowering of African American studies, the era in which white intellectuals debated the “Negro problem” among themselves has ended once and for all. In countless cultural productions and scholarly works from the civil rights era and more recent decades, African Americans are the subjects in the exploration of racial inequality in American history and life. And yet looming among the most popular and enduring works on racial matters since the 1960s is Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, the Depression-era account of Atticus Finch’s legal defense of a Black man wrongly accused of raping a white woman, told through the eyes of Finch’s nine-year-old daughter, Scout.

This article appears as an abstract above, the complete article can be accessed in Project Muse