In January 1941, literati tastemaker Carl van Vechten wrote in mock reproach to Gertrude Stein in Paris—whom he addressed as “Baby Woojums”—chastising her and her partner Alice B. Toklas for their absence when simply everyone else who mattered was there in Manhattan. To further pique the envy of author and art aficionado Stein, he noted his upcoming dinner with Random House publisher Bennett Cerf and artist E. McKnight Kauffer that very night. Such epistolary fragments remind us that Kauffer was, like so many modernists of the first half of the twentieth century, a transatlantic figure immediately recognizable to those who moved in serious artistic and literary circles. Unlike his close friend T. S. Eliot, who became British, Kauffer retained an exilic American citizenship abroad despite more than two decades of residence in the UK. His once prodigious reputation in posters, graphic art, and book design both at home and abroad has been largely forgotten. A recent special exhibit on posters at the Smithsonian’s Cooper Hewitt Design Museum in New York City, however, has brought Kauffer renewed attention, and his artwork for book jackets too has gained a recent critical foothold.1

Kauffer’s perpetual displacement as an expatriate stemmed from impoverished family circumstances at an early age, but his lengthy exile follows the contours of two world wars and the Cold War. Born to first-generation European immigrants, Edward (“Ted”) Kauffer was abandoned in an orphanage for two years, briefly lived with his grandmother in Indiana, and left school at twelve. Drawing was the only constant in an increasingly itinerant life. In 1910, he began work at the bookstore of art dealer Paul Elder in San Francisco. There, he met University of Utah professor Joseph E. McKnight, who, impressed by Kauffer’s talent, financed his way to Europe to study art. Determined to repay McKnight’s confidence in him, Kauffer added his benefactor’s name to his own, becoming E. McKnight Kauffer. After a brief stint at the Art Institute in Chicago, where he attended the groundbreaking Armory Show in 1913, he headed for Germany and France. He would flee Europe for Britain with the onset of the first World War, and while at first stranded there, he would subsequently make his exilic home among London’s interwar modernists.

Apropos of a life on the move, Kauffer’s fame became closely tied to transport. More than book jackets, Kauffer is best known today for the hundreds of iconic posters he created for Frank Pick’s Underground in Britain between 1915 and 1940; in postwar America, he crafted posters for American Airlines that featured the U.S. states and major cities of the world. In his 1924 book The Art of the Poster, Kauffer revealed not only his erudition on the history of posters but the wide-ranging influences and sources for his own groundbreaking designs. One such design was his classic poster Flight (1917–1919) for the Daily Herald, celebrated as the world’s first Cubist poster. In his lifetime, Kauffer collaborated with major artists of the last century, counting many as very close friends—poet Marianne Moore, writer Aldous Huxley, the Bloomsbury coterie that included Virginia and Leonard Woolf, and poet-radical Wyndham Lewis and his Vorticist X Group. Kauffer shared a studio with photographer Man Ray for a time and designed the opening sequence and intertitles for Alfred Hitchcock’s British silent film The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927). His gouache and lithograph illustrations graced the pages and book covers of Britain’s finest presses: Hogarth, Curwen, Gollancz, and Nonesuch. In fact, in 1925, Bennett Cerf rushed to London to model his newly purchased publishing house, the Modern Library, after Francis Meynell’s Nonesuch Press, where Kauffer’s work was both prominent and esteemed. Kauffer more than lived up to McKnight’s initial confidence in him.2

I have long been drawn to the expatriate life and work of Kauffer, as an American overseas off and on for more than three decades in Japan where I teach and research American and Japanese literature and culture. My research also considers how Japan’s woodblock print culture shaped Kauffer’s aesthetic just as it did so many modern poster artists, Impressionists, and Cubists. Originally from Virginia, I had already spent years researching and writing about Kauffer’s relationship to the South, Faulkner, and print culture when I stumbled upon a startling coincidence that brought his work home to me in a direct way. Separate from my literary work on Kauffer and Faulkner, I was writing up the history of a silk mill in Orange, Virginia, just outside of Charlottesville, where my family had worked during WWII, and which had imported its silk from Asia, especially Japan. One day, my aunt sent me a calendar for employees at the mill that had been saved among my grandmother’s personal effects. It is vividly illustrated with Kauffer’s wartime advertisements.

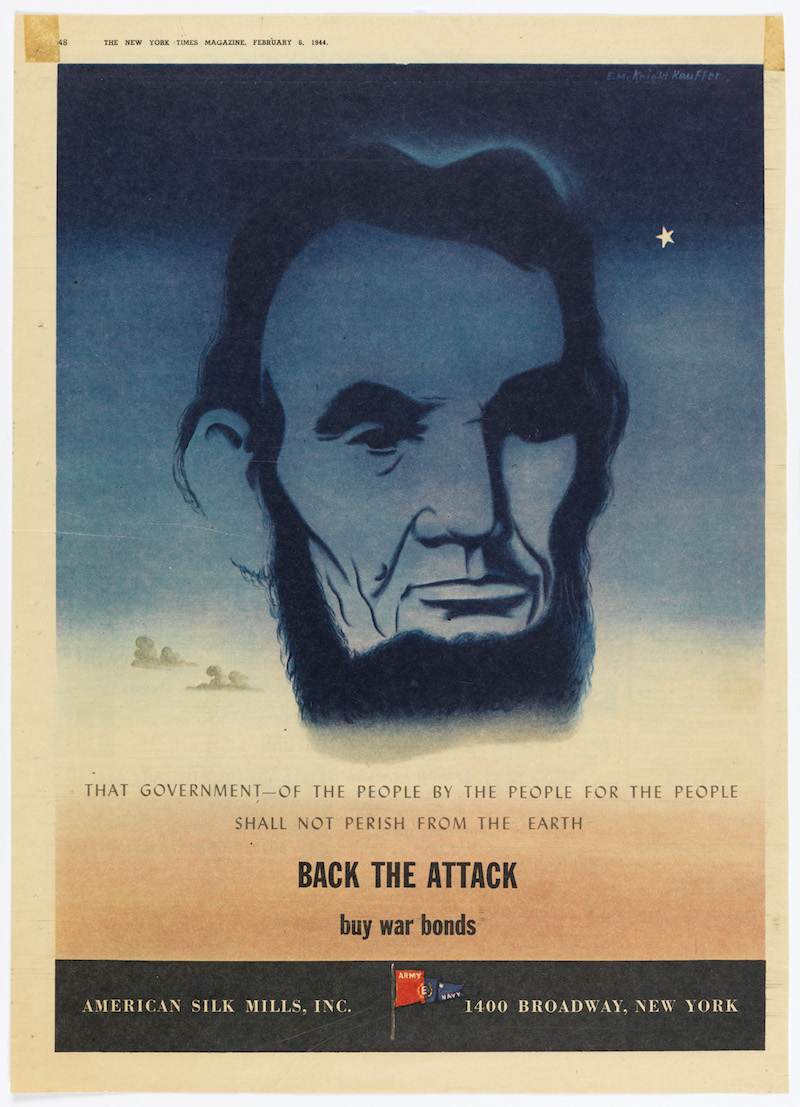

Kauffer produced not only posters and book illustrations but also offset lithographs for advertisements under the aegis of Bernard Waldman’s advertising agency in New York City. During WWII, Kauffer’s advertisements for American Silk Mills appeared in the New York Times Magazine and the New York Times newspaper from 1943 onwards. One such ad expresses the urgency of the war effort with the Liberty Bell ringing against a tilted “moral compass,” while another urges viewers to “Back the Attack” by buying war bonds. Here, reframed for the twentieth century’s war effort, Abraham Lincoln’s pensive face floats against a patriotic sunset shading from a pale white and red to the dark blue of night as a single bright star evokes the beacon of freedom that the North Star represented to formerly enslaved people. Alongside the name of the rural southern mill appears the New York City address of its headquarters.

Another ad, one that was particularly dear to Waldman’s family and framed separately in their home without ad copy, dramatized red, white, and blue tulips emerging behind barbed wire from the bombed-out, debris-strewn, bloodstained soil of Europe. My grandmother’s calendar includes these patriotic flowers. She likely had little or no idea of Kauffer’s global reputation as an artist; like all the mill workers, though, she was proud of buying war bonds and producing parachutes for the war effort, for which they received the “E” award for “Efficiency” from the U.S. government in 1943. Each advertisement featured a small red, white, and blue Army-Navy flag with the “E” at its center, replicating the flag pin that mill workers received at their award ceremony.

In the 1940s, when he was working on the advertisements for American Silk Mills, Kauffer traveled to Richmond, Virginia, as part of his research on that master of Southern Gothic, Edgar Allan Poe. Tasked by Knopf with illustrating a massive two-volume set titled The Borzoi Poe, by 1946 Kauffer had produced numerous surreal and dreamlike landscapes for Poe’s stories. Several brooding Poe portraits hint at Kauffer’s sporadic but decisive turn to more subterranean depths: his first breakdown came in 1941 under the strain of his escape with partner Marion V. Dorn from wartime Britain for the U.S., with little but the clothes on their backs. In his last years, as his marriage broke down and his alienation from the U.S. advertising scene deepened, Kauffer’s depression and excessive drinking would keep dark company with this southern writer whose tales he had once so obsessively illustrated.

Two world wars and the Cold War provided the context, economy, and aesthetics for Kauffer’s exilic displacements, his socialist leanings, and his abstract modernism. In their twentieth-century transnational, transwar context, his provocative illustrations and book jackets for southern and African American writers offer us today a global modernist’s vantage point for assessing the South’s meaning from outside the South. His illustrations for Langston Hughes’s poetry and van Vechten’s fiction place him among major figures who gained their names and cultural currency during the Harlem Renaissance. The Great Migration of millions of African Americans north during the first decades of the twentieth century resulted in Black art and literature produced elsewhere about the South, as in the writings of Zora Neale Hurston and Jean Toomer. From the 1930s through postwar decolonization movements in Africa, the Harlem Renaissance inspired a global Black arts movement centered around Négritude writers Léopold Senghor and Aimé Césaire. From Chicago, Washington, D.C., and New York City to Mexico, Europe, and the Caribbean, a global Harlem helped to create the Global South. Across this South, transnational artists such as Mexican Miguel Covarrubias sketched denizens of Harlem for Vanity Fair while caricaturing Faulkner and van Vechten and illustrating W. C. Handy’s Blues: An Anthology (1926). Covarrubias’s contemporary, Kauffer, moved in the same circles, illustrating African American culture and the South via global networks of print and visual culture.3

His provocative illustrations and book jackets for southern and African American writers offer us today a global modernist’s vantage point for assessing the South’s meaning from outside the South.

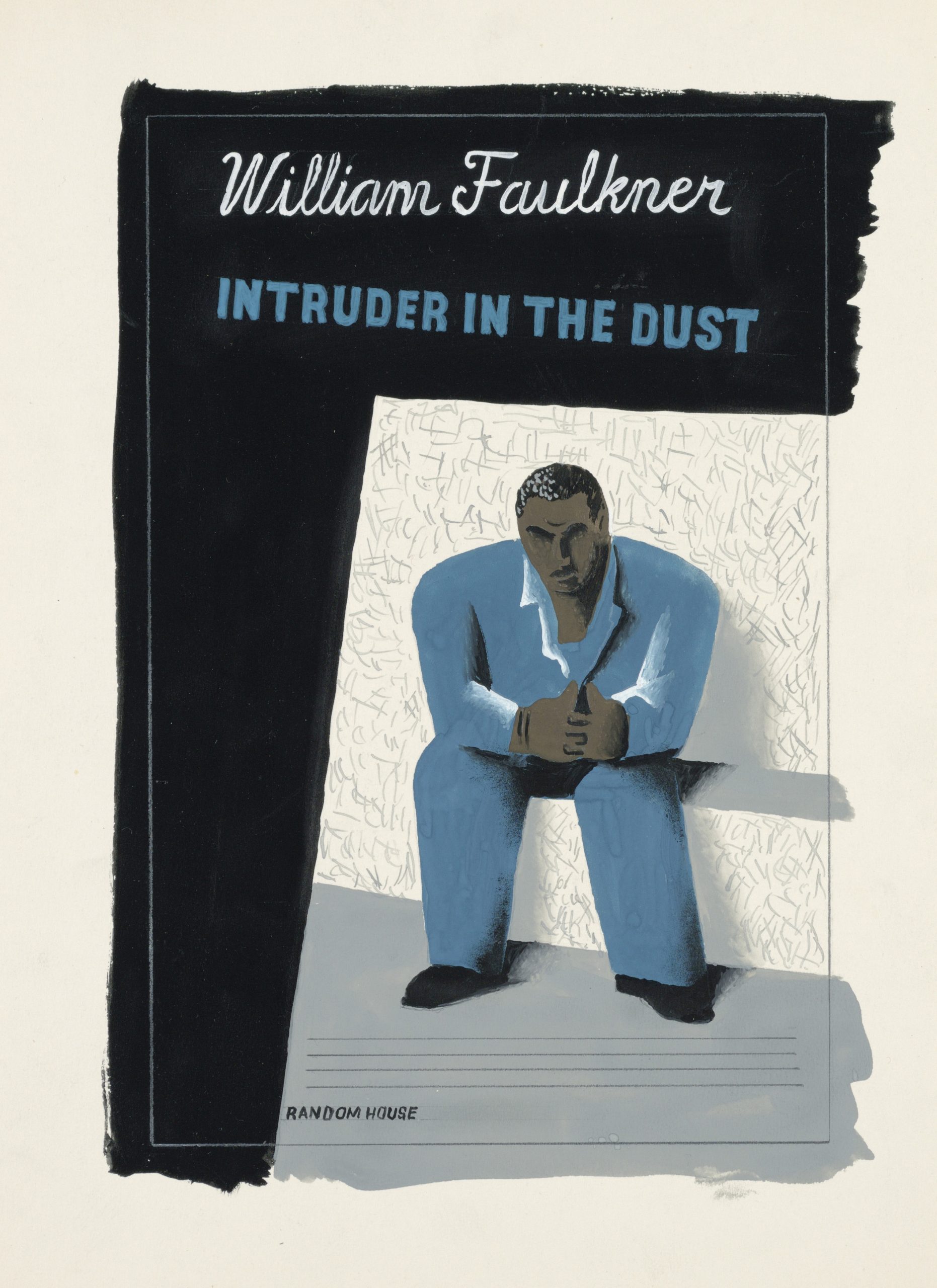

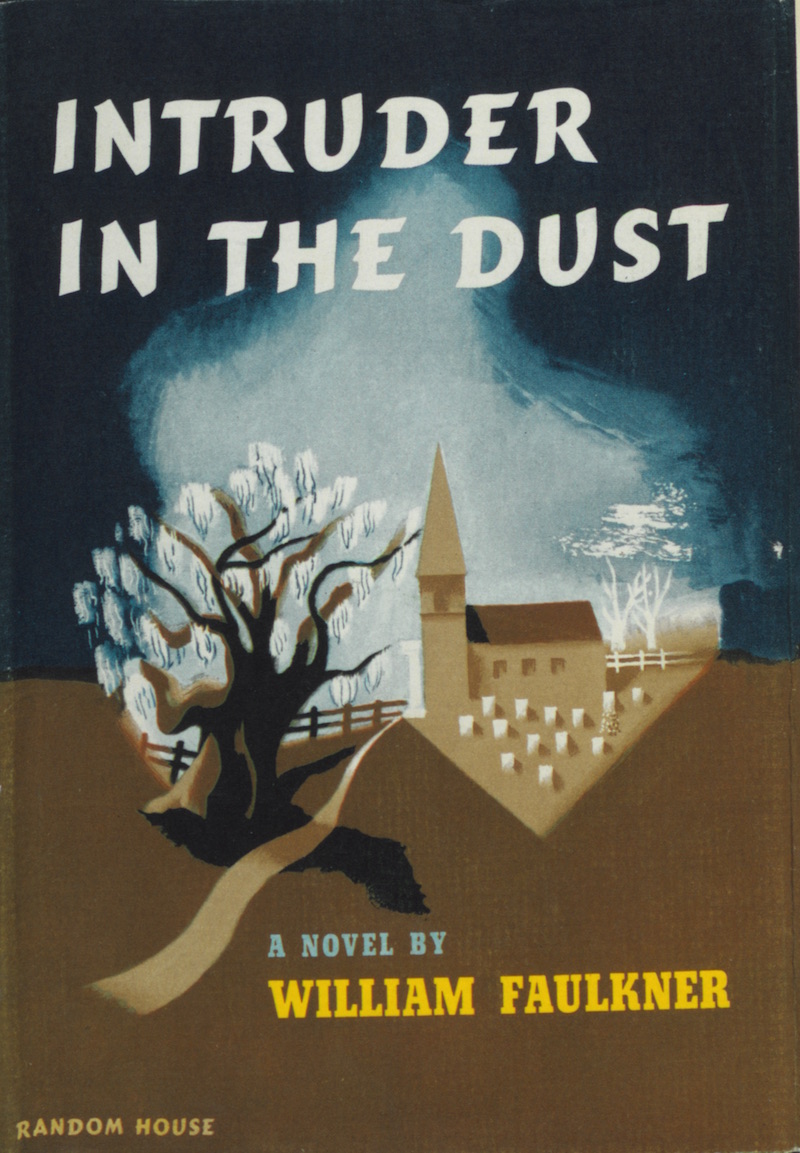

In this context, it is worth lingering on Kauffer’s cover for William Faulkner’s pivotal 1948 novel, Intruder in the Dust, the work that arguably catapulted Faulkner to the Nobel Prize two years later. Critics struggle to understand Faulkner’s global appeal. His reputation remains too often trapped in a false opposition between his modernist experimentation and progressive alliances and the mythic and provincial regionalism that spawned Yoknapatawpha. The life and art of E. McKnight Kauffer as it intersects with Faulkner’s novel alters this paradigm as Kauffer’s art exerts shaping pressure on Faulkner’s fictions of the South. Kauffer’s work is a paratext—material added during the book-making process, seemingly secondary to the author’s text—but it in fact asserts its own perspective from outside both Faulkner’s text and the South. The twentieth-century wartime context informs Kauffer’s view of race relations and Jim Crow violence in the U.S. South. His art reflects the international community’s tendency to interpret southern racial violence as an example of authoritarian trends worldwide. Critics such as Robert H. Brinkmeyer Jr. have demonstrated how the discourse of fascism was applied to the South. Long accustomed to producing WPA posters to decry fascism and promoting the war effort in advertisements as he did for American Silk Mills, Kauffer did not see art and politics at odds, and he likely understood the South’s racial crisis through the lens of his wartime activism. His designs for the cover art and illustrations for novels by Langston Hughes and William Faulkner represent the artist’s engagement with the meaning of the contemporary South and its need for social and political change. Kauffer’s illustrated South suggests a mobile conception of diasporic regionalism and exilic displacement—and complicates prevailing perceptions of racial dynamics in these contexts. Before turning to Kauffer’s illustrated South in the work of Langston Hughes and William Faulkner, it is necessary to look more closely at the context of war and the conditions of exile that fundamentally shaped Kauffer’s life and art, as they are inseparable from his relationship to the politics of advertising.4

War’s Diaspora and Displacements

When World War II broke out in Europe, among the diaspora of European intellectuals and artists seeking asylum abroad were the Americans Kauffer and his partner Marion V. Dorn. They were forced to abandon their English home, work, and belongings to return to the United States on the SS Washington in July 1940. Kauffer’s lifelong exilic displacements began to take their toll with this one, which marked the beginning of Kauffer’s physical and mental decline. Never having sought naturalized citizenship in England and yet never “at home” after returning to the U.S., he struggled with personal guilt and loneliness at having left family and friends behind in wartime Britain. Biographer Mark Haworth-Booth describes how Kauffer’s empathy manifested in the striking Bollingen series cover he made for Nobel Prize–winning poet Saint-John Perse, for his collection of four poems entitled simply Exile (1949):

The illustration is light on dark and consists of a simple graphic treatment of the “X” in Exile. The crossed arms roam free of the island of the word, one hard, straight and rapid in movement, the other leisurely, hand-drawn, exploring beyond the border of the sheet . . . No subject could have aroused Kauffer’s deepest feelings so much as the idea of exile. He was exiled not only from England but also from the America he cherished as an ideal and for which he had found the physical evidence in the South-West.

The word “Exile” is divided at the crossroads “X,” leaving “ile” to resonate with the homonymous “isle” that Haworth-Booth relates to the U.K. as the adopted island country Kauffer was forced to abandon. Just as Perse had to flee France’s Vichy regime in 1940, Kauffer’s displacements too map a perpetual ex-, an outsider status inseparable from wartime dislocations.5

Kauffer’s art exerts shaping pressure on Faulkner’s fictions of the South.

Kauffer’s dramatization of abstract typographical elements with layout and color for Perse’s Exile can also be seen in his most famous book cover, the 1949 design for James Joyce’s Ulysses. Kauffer’s jacket features a strikingly shadowed “U” and an elongated blue “L” in that design reminiscent of the emphasized “L” in the composition for Faulkner’s Light in August jacket in 1950. Besides covers for Faulkner’s Sanctuary (1931), Light in August (1932), Intruder in the Dust, Knight’s Gambit (1949), and Requiem for a Nun (1951), Kauffer designed covers for T. S. Eliot, one of Faulkner’s earliest and strongest literary influences, as he also did for Dashiell Hammett, Faulkner’s drinking buddy in New York, and Faulkner’s fellow Mississippians Richard Wright and Eudora Welty.6

Kauffer made a habit of reading the books whose covers or interior pages he illustrated, and his work on Poe’s and Faulkner’s covers was no different. Book covers were for Kauffer, in effect, “mini posters,” meant to grab a reader’s attention and sell the book but not to exist separately from the contents of the book (as was the case with so many sensational pulp covers during the paperback revolution). In 1937, when the Museum of Modern Art in New York held a one-man exhibition of Kauffer’s posters, Kauffer’s friend Aldous Huxley wrote a memorable foreword to its catalog: rather than depict commodities as symbols for sex or money, “The symbols with which he deals are not symbols of something else; they stand for the particular things which are at the moment under consideration.” Huxley astutely pinpoints Kauffer’s aesthetics here as a concern for material objects as objects of desire that in art, as in advertising, work the complex borders of reality and symbolism. For Huxley, Kauffer’s art sutures text and image to operate on viewers abstractly and subconsciously.7

But the scale of success and recognition that he had gained in England and Europe eluded him in his own country, deepening his sense of exile at home. Initially, new U.S. patrons alleviated his growing depression and disillusionment. Bennett Cerf, for instance, found work for Kauffer at Random House, and one of his earliest covers for the publishing house was a reissued edition of Faulkner’s Sanctuary. Considered advertising and thus a business matter rather than art proper, jacket art is typically anonymous, which is why the case of Sanctuary is so striking: it was dated and prominently signed by its artist in 1940. Active in not only the Omega Workshop of Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, and Vanessa Bell but also the Hogarth Press of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Kauffer was accustomed to publishing and even fine art as labor for which artists should be compensated. He sought the sweet spot between aesthetics and commerce where exchanges in high and low culture could share aims in informing a mass public. In the New York advertising world, he lamented the way an emphasis on money and sex reduced the range and quality of design.8

Working for Bernard Waldman’s advertising agency from 1943 offered Kauffer the artistic and physical freedom to escape New York. Known as “Uncle Ted” by Waldman’s daughter—today’s Frost Medalist (2016) and American Academy of Arts and Letters member (2019), poet Grace Schulman—Kauffer was practically adopted by the Waldman family. Bernard Waldman joined him on some trips he made around the country for the American Airlines posters he would produce through 1953. His travels in Mexico and the Southwest reignited his prewar modernist sensibilities and postwar imagination for the possibilities of art drawn from Indigenous cultures and peoples, folk primitivism, and America’s varied and vast natural landscapes. Kauffer had an eye for the local and aimed to give it universal voice in an international idiom.9

The South in Harlem

When Carl Van Vechten took Kauffer on a tour of Harlem, Kauffer was thrilled by its jazz cabarets and Black nightlife as a visitor to New York and later as a resident. Kauffer relied on van Vechten as a patron and through him had access to major African American literature, art, and culture. While still at Nonesuch Press, Kauffer had illustrated the mostly Black characters in the slave ship mutiny of Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno to much acclaim. His art illustrating Black characters became well known, part and parcel of an international vogue for Harlem and African art during the interwar high modernist period.10

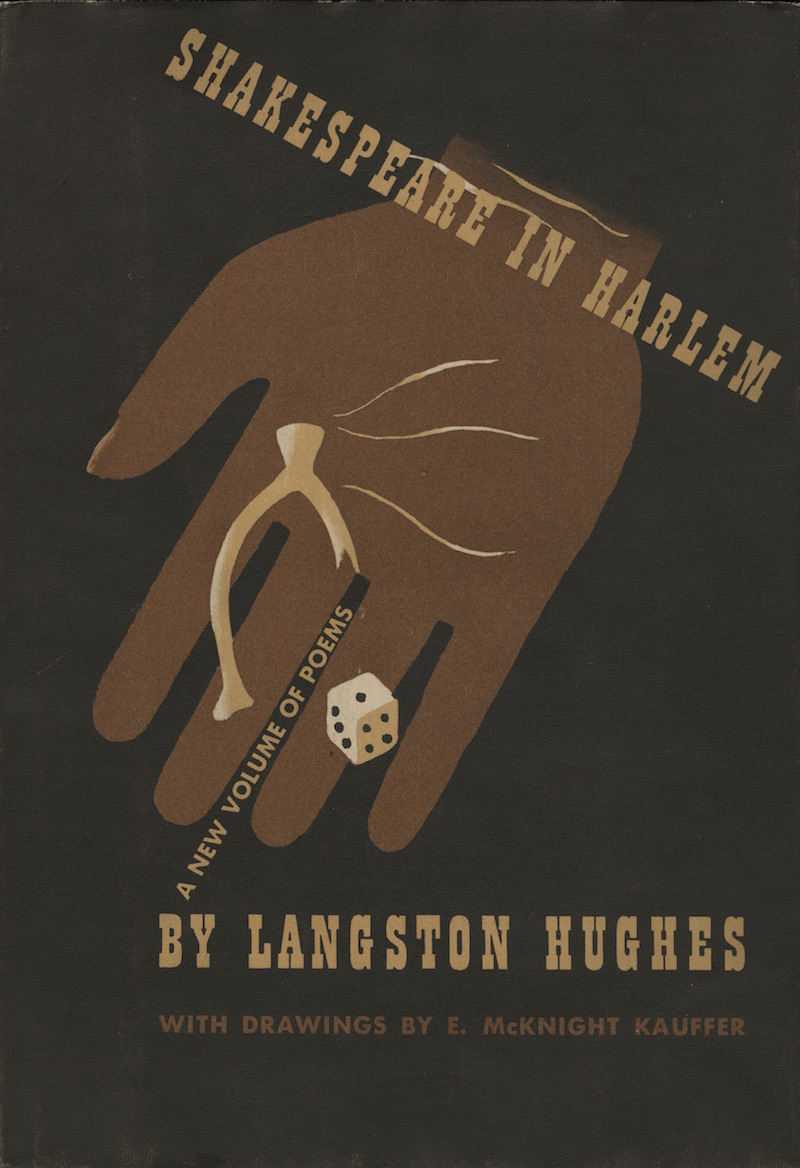

Kauffer’s work for African American writers did not always meet with satisfaction on both sides. Letters exchanged between Langston Hughes and van Vechten show that Hughes was unhappy with Kauffer’s artwork for Shakespeare in Harlem (1942). Hughes wanted his Black characters to appear more modern, so he strongly objected to portrayals of Black hair as “nappy,” or natural. His disgruntlement is measured best by his anecdote to van Vechten that he took off Kauffer’s book jacket at poetry readings, disapproving of the cover’s gambling dice and a wishbone held by a brown hand. Despite Hughes’s desire for updated, positive representations of African Americans, the illustrations in Shakespeare in Harlem are innovative in technique: on the facing page to each of Hughes’s poems, striking white lines etched into rich black matte backgrounds limn Black portraits that stand for the poems’ lyric speakers and at other times offer abstract drawings of specific motifs, such as hands. The technique used in the artwork evokes experimental photograms, or “rayographs.” This technique is usually attributed to Man Ray, who shared a studio and darkroom with Kauffer in London in 1935 when Man Ray produced them. Later, Hughes praised Kauffer’s typography, cover, and illustrations for Shakespeare in Harlem even as he continued to question whether the wrong drawing had not occasionally been used for some poems.11

One such portrait and its poem illustrate the difference between Hughes’s and Kauffer’s artistic engagements with African American culture and contemporary politics. Hughes’s 1941 poem “Southern Mammy Sings” adopts blues rhythms and call-and-response oral traditions in its structure. Humor colors the colloquial wordplay in the opening stanza, in which proper names are given to characters to signal their social roles:

Miss Gardner’s in her garden.

Miss Yardman’s in her yard.

Miss Michaelmas is at de mass

And I am gettin’ tired!

Lawd!

I am gettin’ tired!The nations they is fightin’

And the nations they done fit.

Sometimes I think that white folks

Ain’t worth a little bit.

No, m’am!

Ain’t worth a little bit.

The continued use of dialect keeps the perspective grounded in the South. But by the second stanza, the gaze shifts to politics. It moves beyond the region, evoked by the title, and reinforced by dialect locking arms with place, to the world, where nations compete and wage war. The South’s racial politics are hereby repositioned in a global frame, where the fight for democracy and freedom against fascism and totalitarianism will soon involve America as thoroughly as it has already roiled Europe. The verb “fight” takes as its past tense the creative and comical “fit,” and in the following lines, more than one reader might smile at being tempted to say a more colorful rhyming expletive in lieu of “bit.” The speaker’s Black identity, hinted at in southern dialect, begins to emerge explicitly in the contrast and critique of “white folks.” The poem, in full below, finishes like this:

Last week they lynched a colored boy.

They hung him to a tree.

That colored boy ain’t said a thing

But we all should be free.

Yes, m’am!

We all should be free.Not meanin’ to be sassy

And not meanin’ to be smart—

But sometimes I think that white folks

Just ain’t got no heart.

No, m’am!

Just ain’t got no heart.

The vital third stanza ups the ante in a blues key as the speaker doubles down on a political theme close to home: a “colored boy” has been lynched for speaking his mind about racial justice. The second and final stanzas frame this one, as the speaker talks back (gets “smart” and “sassy”) to the rationalized violence and morality of “white people” and, by extension, the nations they built and the civilization they claim to fight for. The final stanza opens by deprecating and disavowing the power of the crime for which the boy was lynched—speaking one’s mind—resolving finally into a resigned moral condemnation of the absent “heart” of white society. By the poem’s conclusion, a maternal southern voice has said her piece as she “sings” away the lynching blues. Her voice merges intertextually to earlier, starkly activist and angry voices in Hughes’s poetry: his controversial language, Black Christ imagery, and Mother Mary “mammy” in “Christ in Alabama” (1931) would appear in the Scottsboro Limited pamphlet published by the Golden Stair Press of van Vechten and Prentiss Taylor in 1932. Both poems draw the connection between the South’s lynching violence and the fight against fascism abroad since WWI, points made even earlier and more sharply in Hughes’s “The Colored Soldier” (1919) from The Negro Mother and Other Dramatic Recitations (1931).12

Hughes’s “Southern Mammy Sings” faces a Kauffer outline that is clearly male, not female, and but for the slouchy hat and larger mouth could almost be mistaken for the jacket image he had done of Popeye for Faulkner’s Sanctuary. Little wonder that Langston Hughes initially questioned whether this image belonged with this poem. Only by grasping Kauffer’s process of reworking and developing images in his designs can we better understand such decisions. Whether in advertising or art, Kauffer rarely “illustrated” a text directly, much less created strictly representational figures. Concerned with ideas and symbols, he arranged simplified images or photos together with elements of color and typography to juxtapose reproducible elements in a composition meant to manipulate the eye even as the composition might also “speak” for itself in its own visual idiom. A devotee of lithographs and offset printing, Kauffer strived for originality in design but, as a print artist, not to create something one of a kind, per se; that is, he labored over early “roughs,” then with assistants transformed final images into simplified elements with few colors to be reproduced in layers. Kauffer revised and repeated fundamental but distinctive shapes and character types throughout his oeuvre, including birds, trees, humans, and hands, gestures and postures, and arguably Black and white character types, in lieu of more conventional realism.

Kauffer’s techniques for Hughes’s book were innovative and modern, and he felt no need to revise or decorate Hughes’s poem by literally depicting its topic; instead, his artwork plays its own visual tunes in a riff alongside Hughes’s textual blues. Rather than depicting a “southern mammy” stereotype or sensationalizing a lynched youth, Kauffer resurrects a rural southern Black youth before his murder in the lines of the poem. Perhaps resurrected, too, is a variation on Sanctuary‘s cover from the year before: Kauffer’s rural southern faces, Black or white, innocent victim or criminal racist, at times converge. These images are reminiscent of Rev. Gail Hightower’s final whirring wheel vision in Light in August, where many faces momentarily blur, and the lynched Joe Christmas merges with his murderer Percy Grimm, whom Faulkner himself identified as a protofascist. False moral equivalences? For Faulkner, arguably so, but for Kauffer, more likely an artist combining metonymic elements from a very different palette he imagined and drew of the South from outside the South. Unlike a stereotype, a metonym cannot stand alone, and never rests in one place: Kauffer’s South is forged of a range of associative elements from his modernist palette that are endlessly revised, constantly reconfiguring and aligning with each viewer’s eye and mind in compositions that test new meanings.13

Faulkner’s Faces, Kauffer’s Strange Fruit

Faulkner traveled in many of the same circles as Kauffer when he was in New York or in Hollywood, and besides sharing an interest in bookmaking, caricature, and illustration, he was as likely to run into him in Random House’s offices as at the Algonquin or celebrity gatherings. That Kauffer gave Faulkner the original artwork for Requiem for a Nun—recently discovered in the University of Mississippi’s Special Collections—and that Faulkner acknowledged it in a signed thank-you note on Random House stationery to Kauffer, establishes once and for all these two artists’ shared appreciation for each other’s work.14

Albeit in different ways, they also shared a social conscience. This conscience converged as a commercial and aesthetic transaction around the issue of race relations and civil rights during the production of Faulkner’s novel and its film adaptation, Intruder in the Dust. The novel’s plot centers on Lucas Beauchamp, a Black man accused of a crime he did not commit and who faces a lynch mob, while its narration comes through a fourteen-year-old white boy, Chick Mallison, who tries to repay an old debt he feels he owes Lucas by solving the crime. Along the way, Chick’s uncle Gavin Stevens, the town’s lawyer, soliloquizes on race relations, arguing against federal (northern) interference in the problems of the South that only the South must resolve. Critics often cast Gavin as Faulkner’s mouthpiece, recalling Faulkner’s “go slow” attitude just when civil rights and anti-lynching legislation was a matter of contemporary social and political debate. A more complex picture emerges, though, when we look at correspondence between Faulkner, Random House, and mgm, which committed to making a film even before the novel was published. Wary of a “message” novel and film with a political agenda, or one that would be pigeonholed as an anti-lynching piece, Cerf’s Random House and Louis B. Mayer’s mgm wanted to downplay Lucas Beauchamp’s role and stress instead the Huck Finn–like character of Chick Mallison coming of age, or the viciousness of the Gowries, the white hill family guilty of the crimes in the novel besides leading the lynch mob. In response to Cerf’s repeated efforts to get Faulkner to revise his title to “Beat Four,” where the Gowries live, Faulkner became more stubborn. Deploying a southern storyteller’s inclination for tall tales and dissembling humor, Faulkner’s letters show him deflecting his editor’s requests with long-winded pretenses at cooperation in making the changes before circling back in comic obstinacy by the end, insisting on his original title. Just what Faulkner intended on the matter of race, though, remains an open question.15

Hints, though, can be found in Faulkner’s letter describing the novel for his agent Harold Ober in early 1948. He writes:

The story is a mystery-murder though the theme is more [the] relationship between Negro and white, specifically or rather the premise being that the white people in the south, before the North or the govt. or anyone else, owe and must pay a responsibility to the Negro. But it’s a story; nobody preaches in it. I may have told you the idea, which I have had for some time—a Negro in jail accused of murder and waiting for the white folks to drag him out and pour gasoline over him and set him on fire, is the detective, solves the crime because he goddamn has to to keep from being lynched, by asking people to go somewhere and look at something and then come back and tell him what they found.

Despite Faulkner’s rejection of federal intervention in the South, it is not necessary to read this solely through the lens of reactionary politics; rather, the passionate frustration of the letter (“because he goddamn has to” suggests that “white folks” are clueless, unable to see their own racism without being led step-by-step to it by Lucas) proposes an argument more common in our own time than in 1948. Precisely because Intruder is inaugurated by a financial debt that Chick Mallison owes Lucas Beauchamp, one complicated by race, Faulkner’s letter suggests that only some kind of racial reparations will appease accumulated generations of white debt. The letter stresses that the white South first and foremost must step up to repay African Americans both literally and morally; that African Americans must play a role in making whites solve, and thereby recognize, the crimes whites themselves have committed; that the singular representative crime here is the lynching of innocent people. Erik Dussere and other critics have placed a close reading of the novel and this letter in the context of what today’s progressive public intellectuals, such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, describe as the logic of racial reparations. Racial reparations give the novel’s central problem of “debt” its force and focus: as a debt both factual and abstract, it is also by turns calculable in monetary terms and incalculable morally; it is both personal and historical, and located in policies, misdeeds, and crimes compounded by past violations of family and community ties. It is as if Faulkner’s Intruder works through a case study of what a modern correction of historical wrongs might look like, finally to conclude that some kind of reparations are needed on all fronts—financial and social, between white and Black families—before the country can heal and its contemporary fratricides cease.16

While Faulkner’s case study is fictional, actual lynchings served as models for the looming threat hanging over Lucas Beauchamp in Faulkner’s novel. Faulkner biographer Joseph Blotner long ago named Elwood Higginbotham as the most likely source for Beauchamp and, since then, Faulkner scholar Arthur F. Kinney has written that Faulkner’s nephew, only eight at the time, confessed to Kinney as an adult that he attended Higginbotham’s 1935 lynching and was threatened into silence on what he had witnessed. In this way, Faulkner’s family, not just his community in general, was directly implicated in the incident.17

Higginbotham’s life and death continue to animate a much-needed national discussion today, thanks to research by then–Northeastern University law student Kyleen Burke of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project. Building on Burke’s documentation, journalism professor Vanessa Gregory wrote an article for the New York Times Magazine based on her interviews with Higginbotham’s remaining family members about what they know about the murder and why it has been difficult for them to learn the true story or even mourn him properly. Spurring more such acts of remembering families and their stories, the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, documents Higginbotham’s death in Lafayette County, along with more than 4,700 others in counties across the United States in an ongoing project. When I read Faulkner’s Intruder today, the shadow of Elwood Higginbotham’s story emerges into the light, fact annotates fiction, and the past catches up to its future. Kauffer’s first edition book jacket contributes to a more deeply contextualized understanding of Faulkner’s novel, reinforcing the sense that a tangled social conscience in multiple voices is wrestling through moral as well as fictional knots, making it something more than Faulkner’s professed “mystery-murder” alone.18

Kauffer’s first edition book jacket contributes to a more deeply contextualized understanding of Faulkner’s novel, reinforcing the sense that a tangled social conscience in multiple voices is wrestling through moral as well as fictional knots.

A church and its cemetery, with a path leading up to its front door’s lone classical column, appear on Intruder‘s cover. In the foreground is a tree dripping with Spanish moss. Depicted in Kauffer’s stylized and dreamlike way, the composition is at once obvious and deceptive. One’s gaze is drawn to what appears to be strictly representational references to the story: the tree appears at first glance a mere Southern Gothic cliché, while the recently dug grave in the cemetery stands for the series of grave swappings that take place in Intruder before Chick and his helpmates find the real murder victim and his murderer. A sustained look at the left side of the tree with its Spanish moss, however, reveals something more: several heavy-lidded African faces entangled in profile. A pause, and we realize that we are looking at Kauffer’s rendering of the “strange fruit” that Faulkner’s novel threatens to make of Lucas Beauchamp, and finally evades.

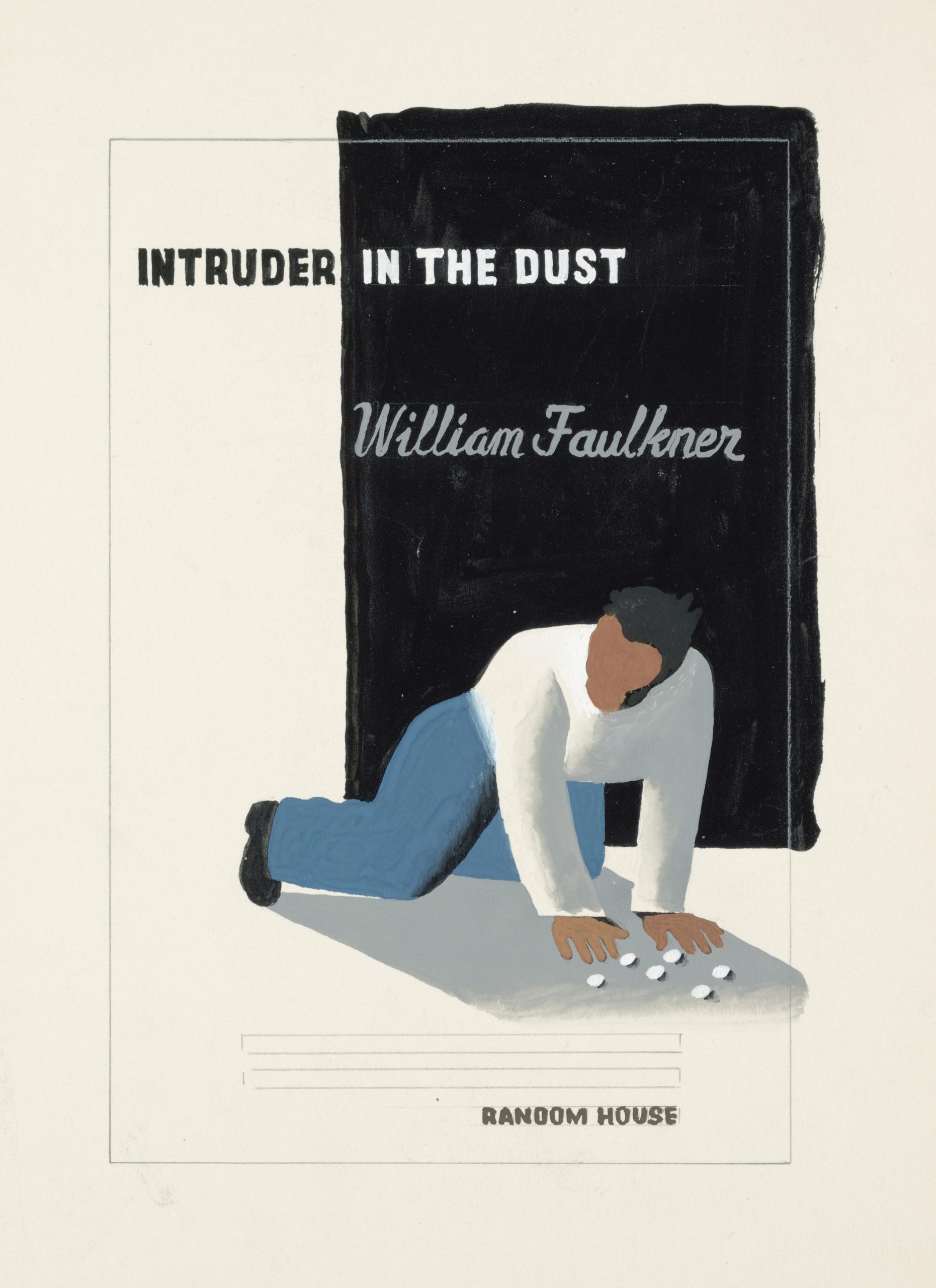

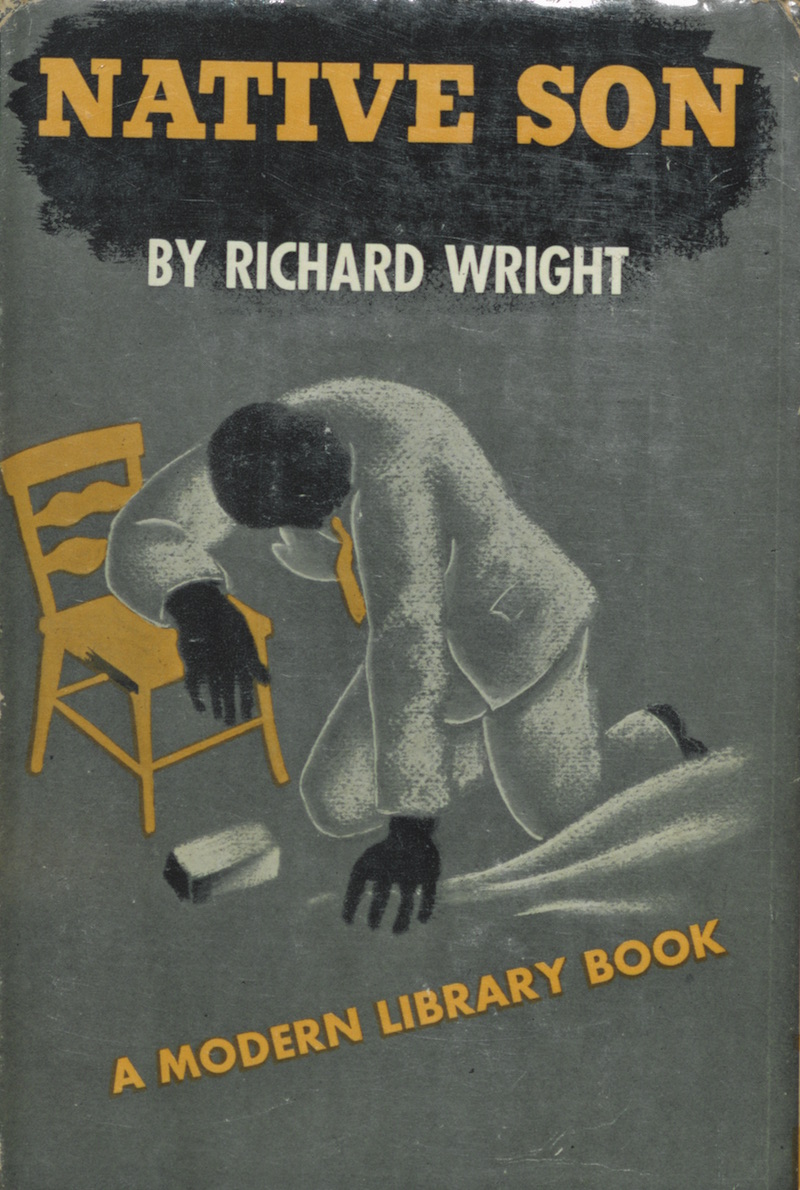

Whether Kauffer faced pressures similar to Faulkner, who had to reframe Intruder to avoid its categorization as a “race novel,” is impossible to say, but two earlier studies for the jacket suggest that Kauffer had explored a cover akin to one that he had done for Native Son (1940) by Richard Wright. One represents a Black man in a loose-fitting suit sitting in a confined space evocative of Lucas Beauchamp’s jail cell or, more symbolically perhaps, the poverty and racial isolation of Bigger Thomas trapped in white society at large. The other related study shows the Black figure scrambling for coins on the floor, in apparent allusion to the money Chick drops insolently on the floor when he tries to pay off his debt to Lucas with mere money (although in Faulkner’s novel it is not Lucas who scrambles for the money but two Black boys). From today’s vantage point, both scenes evoke more the opening battle royale scenes of Ralph Ellison’s later Invisible Man (1952) for which Kauffer would later design a very different, and now classic, cover. Kauffer’s studies for Intruder‘s final book jacket offer a rare glimpse into the artist’s process of reading and thinking through the cover art for the story Kauffer thought Faulkner’s Intruder was trying to tell. Compared to these early studies, the radically different final cover appears to give in to pressures to avoid the novel’s race message and replace the representational figure of a Black man with a more abstract composition. In seeing at last its strange fruit, though, we recognize the artist’s deliberate subversion of everything we know about the publishing history of Intruder in the Dust. Here, he either insists on a moral point he found in Faulkner’s story or slyly inserts one he himself wanted to say, thwarting author and publisher.

What kind of social conscience is at work here? We have almost no statements on race and social conscience made by Kauffer, save in April 1946 at MOMA when he spoke at a forum of the Independent Citizens’ Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions (ICCASP), a group often narrowly accused of Communist sympathies despite its wide-ranging membership of artists, actors, professionals, and New Deal supporters. ICCASP advocated for democracy, peace, and a living wage in the U.S. and abroad (its members included the actor and later U.S. President Ronald Reagan as well as Black intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois). In his “Remarks,” Kauffer raised questions about the role of the artist in achieving social and political good in society.

For artists to play any practical and significant part in the post-war plans, we shall have to think of ourselves first as citizens and being a citizen makes imperative certain obligations . . . We realize now that in common with other minority groups we must form ourselves into a body of opinion that we must have, and that we must make clear to those in whose hands the post-war pattern will take shape that we are a responsible body, an essential body and a practical body . . .

Propaganda flares up and then dies away and no matter how excellent it may be as art and word its duration is only for the purpose of directing thought and act for a particular objective. Naturally, the exceptional artists working in this field will give the presentation an [aesthetic] content which from a civilizing point of view has value over and above the ordinary. Every good poster, booklet, card, is a protest against the lazy and usual methods of appeal through sex, snobbism, fear and corruptive sentimentality. Indirectly therefore, we make contribution to more civilizing influences.

. . . It is easier to see where we designers can fit into the activities of postwar plans. New forms of education, social problems of re-adjustment, racial discrimination and the Negro problem.

Strikingly, Kauffer’s defense and redefinition of propaganda’s role echoes W. E. B. Du Bois in “Criteria of Negro Art,” first published in The Crisis in 1926, which asserted that “all art is propaganda.” For Du Bois, African Americans in particular must wrestle with the “propaganda” of a dominant white discourse that misrepresents them, necessitating in turn a counterpropaganda as self-defense and in the service of racial uplift and advancement. For Kauffer, who spent both most of his life fleeing war or fighting fascism’s threat with propaganda produced side by side with the world’s avant-garde artists and the WPA, artists could be both dangerous and vital to vibrant adversarial debate and a free society. In his “Remarks,” he advises the “minority group” of artists to take up the problems of “racial discrimination and the Negro problem,” providing an explicit statement of social conscience and advocacy of art for social change.19

One can hardly claim that Faulkner believed in equality in race relations or even supported the anti-lynching legislation of the 1940s, which failed to pass in the end; too often, he sounds like Gavin Stevens in Intruder, justifying the South even when it was wrong. However flawed and limited these views might appear today, we would be remiss to ignore that in his own time it was Faulkner’s occasionally “liberal” views that ruffled feathers at home. His ideas approached those of his friend, a former racist turned self-professed “southern liberal,” Hodding Carter II, an author, journalist, and Pulitzer Prize winner of editorials attacking racial injustice. Moreover, Faulkner strongly backed fellow southerner Clarence Brown as director for the film version of Intruder. Brown had sought out the project over the objections of MGM’s head, Louis B. Mayer, who was adamant that a race picture would not sell. Brown never made a secret of his personal reasons for wanting to make Faulkner’s novel into a film: he had witnessed lynching in the Atlanta race riot of 1906 when he was a boy about the same age as Chick, and he had never forgotten it. Brown’s choice of Juano Hernandez to play the role of Lucas Beauchamp itself warrants attention in this context: Hernandez would have been known to current audiences for his New York stage performances of Lillian Smith’s banned and controversial novel of miscegenation and race relations, Strange Fruit (1944). Billie Holiday’s earlier 1939 protest song, “Strange Fruit,” penned by Jewish songwriter Abel Meeropol upon seeing photographs of a lynching, together with Hernandez’s stage reputation, surely reverberated Intruder‘s racial theme for contemporary readers and filmgoers. Brown’s willingness to make the film in Faulkner’s own Oxford, Mississippi, using local people as actors, speaks to both his and Faulkner’s desire to foment revelation and dialogue about race relations in the South, not just outside of it, despite the fact that profit and publicity motives also played a role in the choice of location endorsed by both Random House and MGM.20

In the rather uneven novel that is Intruder, always struggling between telling a story of Jim Crow race relations of its time and of a “mystery-murder” solved by a boy hero, Faulkner struggles. It is as if he tries on the voice of Gavin Stevens only to then take on that of Chick resisting and acting on his own; his narrators tease out facets of a reparations argument even as his narrative also stages its refutation in Chick’s comical and childish responses to Lucas or the murderous intent of the racist mob. If in his lifetime Faulkner did not support racial equality, at times he spoke out against racial injustice, as with the murder of Emmett Till. His fiction often complicates the thorny problems of racial violence, cross-racial kinship, social debt, and justice—and Intruder is no exception.21

Faulkner explicitly depicts a different kind of face in his novel than Kauffer encodes in the “strange fruit” on its book jacket. Near the end of Intruder, a feverish Chick, taken ill after staying out all night solving the murder, sees a “Face”:

And it was not even a face now because their backs were toward him but the back of a head, the composite one back of one Head one fragile mush-filled bulb indefensible as an egg yet terrible in its concorded unanimity rushing not at him but away.

“They ran,” he said. “They saved their consciences a good ten cents by not having to buy him a package of tobacco to show they had forgiven him.”

. . . a Face, the composite Face of his native kind his native land, his people his blood his own with whom it had been his joy and pride and hope to be found worthy to present one united unbreakable front to the dark abyss the night—a Face monstrous unravening omnivorous and not even uninsatiate, not frustrated nor even thwarted, not biding nor waiting and not even needing to be patient since yesterday today and tomorrow are Is: Indivisible: One.

Chick describes here his desperate desire to put forth a brave and proud “face” that lives up to the ideals he once believed in, what he wanted to believe “his native kind his native land, his people his blood his own” to be. And yet what Chick announces from the outset is his disillusionment in seeing something else: his people turn their faces away in cowardly flight from the responsibility either to apologize or recognize the wrong done to Lucas. By the end of the passage, the Face has become a unified abstraction of objective Truth, Justice, and Time itself, heedless of either Chick’s individual attempts to make his mark by doing what is right, or the mob’s failure to face up to their own injustice. By novel’s end, Lucas is not lynched; instead of Lucas “paying” for his crime with death as expected, Crawford Gowrie commits suicide in jail. Following on a plot filled with grave swappings, finally Lucas’s own expected grave is swapped for that of the real murderer, Gowrie (“not a life saved from death nor even a death saved from shame”). Faulkner acts in accordance with his belief that the South had to criticize its own to inaugurate change. When Faulkner “substitutes” a Black man’s lynching with a white murderer’s suicide, he critiques white racism as regressive and self-destructive (for society, even suicidal), not only barbaric in its extralegal violence toward African Americans. The cowardly Head, represented by Crawford Gowrie, who literally headed up the mob and finally commits suicide as the real murderer, usurps the place of the Face that Chick had hoped would represent him and “his own.”22

Kauffer subliminally memorializes and encodes the history of lynching in the Black faces on his cover, the very faces that the cowardly run away from in Faulkner’s text.

It is as if the Black faces on Kauffer’s cover are in dialogue with Intruder‘s cowardly Head, Chick’s imagined white Face, and Faulkner’s final “monstrous” universal Face. In almost existential terms, Chick repeats the necessity of remaining “anonymous” in his efforts to prove Lucas’s innocence: his deeds must be free of credit or they might be “befouled” by personal “gain,” no matter his good faith attempts to help Lucas, better mankind, or contribute to the sum of what makes up a human being. In making his own anonymous contribution to Chick’s multisided, ambiguous vision of the white universal Face, Kauffer subliminally memorializes and encodes the history of lynching in the Black faces on his cover, the very faces that the cowardly run away from in Faulkner’s text.

Of a piece with his “Remarks” before ICCASP membership two years before, with this cover Kauffer practiced what he preached: he used his artistic talent and position to amplify a political facet of Faulkner’s contemporary South, expressing the injustice the novel all but suppresses by its awkwardly happy ending. That it has taken until now for anyone to see the Black faces in Kauffer’s cover perhaps attests to just how ideologically blinding certain social and political forces have been when coupled with the formidable industry built around Faulkner’s celebrity. The value of Kauffer’s paratextual art will best be gauged in the context of his own life and times, but it surely sheds light on our own.

This essay first appeared in the Here/Away issue (vol. 25, no. 4: Winter 2019).

Mary A. Knighton, professor of literature at Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo, has taught and published widely in both American and modern Japanese literature and culture. In late 2019, she will be guest curator for a temporary exhibit at the James Madison Museum of Orange County Heritage in Virginia that traces the regional and global ties of a local silk mill. Her current book project is titled Insect Selves: Posthumanism in Modern Japanese Literature and Culture.NOTES

- The degree of Kauffer’s fame as a modernist is evident in the cultural reference to him and the company he kept in Evelyn Waugh’s novel, Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred and Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1945), 27; Ellen Lupton, How Posters Work (New York: Cooper Hewitt Design Museum, 2015); Mary A. Knighton, “William Faulkner’s Illustrious Circles: Double-Dealing Caricatures in Style and Taste,” in Faulkner and Print Culture, eds. Jay Watson, Jaime Harker, and James G. Thomas Jr. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017), 28–50.

- E. McKnight Kauffer, ed., The Art of the Poster: Its Origin, Evolution and Purpose (London: Cecil Palmer, 1924); Mark Haworth-Booth, E. McKnight Kauffer: A Designer and His Public, 2nd ed. (London: V&A, 2005), 17–18.

- New York was a hub of national and global publishing, which spurred global modernists’ collaboration. See George Hutchinson, The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

- Robert H. Brinkmeyer Jr., The Fourth Ghost: White Southern Writers and European Fascism, 1930–1950 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009). On Pan-African global arts movements and the Global South, see Brent Hayes Edwards, The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003); Jon Smith and Deborah Cohn, eds., Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Leigh Anne Duck, The Nation’s Region: Southern Modernism, Segregation, and U.S. Nationalism (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2006); Scott Romine, “Where is Southern Literature? The Practice of Place in a Postsouthern Age,” in South to a New Place: Region, Literature, Culture, eds. Suzanne W. Jones and Sharon Monteith (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002), 23–43; and Annette Trefzer and Ann J. Abadie, eds., Global Faulkner (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009).

- Haworth-Booth, Designer, 96–101, 107–108. Kauffer left behind his first wife, American concert pianist Grace Ehrlich, and their child, Ann. I am grateful to Kauffer’s grandson, Simon Rendall, for his permission to use Kauffer’s visual art and for the background history and anecdotes he has shared with me over the years.

- Ned Drew and Paul Sternberger, By Its Cover: Modern American Book Cover Design (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2005), 8–17. See John Updike’s praise of Kauffer’s Ulysses cover in “Deceptively Conceptual,” New Yorker, October 9, 2005, http://www.newyorkercom/magazine/2005/10/17/deceptively-conceptual.

- Knighton, “Illustrious Circles,” 38–41; Haworth-Booth, Designer, 99. See Huxley’s foreword in the exhibition catalogue, Posters by E. McKnight Kauffer (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1937).

- Kauffer takes the New York advertising world to task by first praising the origins of America’s distinctive ingenuity in the snake oil salesman and P. T. Barnum before concluding that what worked for them should be adapted today to avoid “hitting below the belt” (16) in a focus on sex and money. “Advertising Art Now,” A-D Magazine, 1941, 1–16. In the accompanying sketches, he suggests that they would do well to learn from great poster designers such as Toulouse-Lautrec.

- Haworth-Booth, Designer, 104. Today, Grace Schulman is a professor at Baruch College and a poet of international stature whose close relationship to Marianne Moore was shared by her “Uncle Ted.” I thank her invaluable generosity in sharing letters and stories, as well as guiding advice to the archives of her Kauffer materials at the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum and Yale University’s Beinecke Library. See Grace Schulman, “Gift from a Lost World,” Yale Review 85, no. 4 (October 1997): 121–134.

- Joseph Blotner, Faulkner: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1974), 1: 743. Haworth-Booth confirms my own personal correspondence with Simon Rendall that Kauffer frequented jazz cabarets in Harlem, at times with Lord Jeremy Hutchinson (101, fn10 on 115). Kauffer, as did Covarrubias, completed a set of illustrations for van Vechten’s controversial roman à clef of Harlem social life in 1926 but they were never used. The drawings remain extant in the MOMA archives and the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum. See Bruce Kellner, ed., The Splendid Drunken Twenties: Selections from the Daybooks, 1922–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), esp. 300.

- Emily Bernard, ed., Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, 1925–1964 (New York: Knopf, 2001), 198–206; Brian Webb and Peyton Skipwith, E. McKnight Kauffer: Design (Woodbridge, UK: Antique Collectors Club, 2007), 25; Bernard, Remember Me, 205.

- Langston Hughes, Shakespeare in Harlem (New York: Knopf, 1942), 74–76.

- William Faulkner’s comment on Percy Grimm was said in response to a question at a talk; see Frederick L. Gwynn and Joseph Blotner, eds., Faulkner in the University: Class Conferences at the University of Virginia, 1957–1958 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1959), 41.

- Mary A. Knighton, “Lines of Correspondence: E. McKnight Kauffer’s Original Dust Jacket Art for William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun,” Notes and Queries 64, no. 4 (November 2017): 665–668.

- Robert W. Hamblin, “Teaching Intruder in the Dust through Its Political and Historical Context,” in A Gathering of Evidence: Essays on William Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust, eds. Michel Gresset and Patrick Samway SJ (Philadelphia: St. Joseph’s University Press, 2004), 57–73. In a lengthy internal memo at Random House, Bennett Cerf acknowledged race as the story’s core, but concluded with a recommendation that the title be changed to “Beat Four”; see “Report on Faulkner Book,” April 27, 1948, William Faulkner Collection, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia. The language of “substitution” and “sleight of hand” is repeated frequently in letters between Faulkner, Harold Ober, and Cerf debating the title between March and May of 1948. See Joseph Blotner, ed., Selected Letters of William Faulkner (New York: Vintage, 1978), 264–268.

- Blotner, Letters, 262. Erik Dussere has argued that the logic of debt in the novel speaks to historical reparations in the form of affirmative action; see “The Debts of History: Southern Honor, Affirmative Action, and Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust,” Faulkner Journal 17, no. 1 (Fall 2001): 37–57. Elsewhere, I deepen this interpretation of Faulkner’s novel as one that explores the question of reparations; see “Racial Debts, Individual Slights, and Sleights of Hand,” in Faulkner and Money, eds. Jay Watson and James G. Thomas Jr. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2019), 186–207. See also Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” Atlantic, June 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631; and Randall Robinson, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks (New York: Dutton, 2000).

- Blotner, Faulkner, 2: 1246. For details of the 1908 Oxford lynching of Nelse Patton, see Blotner, Faulkner, 1:113–114. Kinney describes hearing the story of Higginbotham’s lynching from Faulkner’s nephew Jimmy Faulkner, who witnessed it. See Arthur F. Kinney, “Unscrambling Surprises,” Connotations 15, nos. 1–3 (2005/2006): 17–29, esp. 19; and “Mob Lynches Negro,” New York Times, September 19, 1935, 21.

- Vanessa Gregory, “A Lynching’s Long Shadow,” New York Times Magazine, April 25, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/25/magazine/a-lynchings-long-shadow.html. See the work of Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, including the 2017 Brooklyn Museum Exhibit, “The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America,” which can be found online: https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/. Also see Equal Justice Initiative, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, 3rd ed. (Montgomery, AL: Equal Justice Initiative, 2017).

- E. McKnight Kauffer, “Remarks Delivered in a Lecture by E. McKnight Kauffer at the Museum of Modern Art,” n.d., Grace Schulman Papers, Yale University Archives. Although Haworth-Booth claims these remarks were delivered in April 1948 at a Committee on Art and Education meeting (101), references in the “Remarks” themselves indicate the occasion was more likely an April 1946 ICCASP forum. W. E. B. Du Bois, “Criteria of Negro Art.” Crisis 32, no. 6 (October 1926): 290–297, esp. 295.

- Hodding Carter, “A Southern Liberal Looks at Civil Rights,” New York Times Magazine, August 8, 1948, 10ff. In his entry on Carter, Hamblin points to letters in which Faulkner expressed support for Carter’s more moderate views; see A William Faulkner Encyclopedia, eds. Robert W. Hamblin and Charles Peek (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999), 61–62. Regina Fadiman interviewed Brown about the film and learned of his trauma at sixteen years old (the same age as Chick in the novel). See Regina Fadiman, Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust: Novel into Film: The Screenplay by Ben Maddow as Adapted for Film by Clarence Brown (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1978), 27–28. Details about Brown’s relationship to Faulkner as well as about casting local Oxford residents in the film are traced in Fadiman, Novel into Film.

- See Christopher Metress, ed., The Lynching of Emmett Till: A Documentary Narrative (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 42–43. An insightful debate among Faulkner scholars about Faulkner and race can be found in Connotations: A Journal for Critical Debate, inaugurated with an article by Arthur F. Kinney, “Faulkner and Racism,” Connotations 3, no. 3 (1993/1994): 265–278; also online at https://www.connotations.de/article/arthur-fkinney-faulkner-and-racism.

- William Faulkner, Intruder in the Dust (New York: Random House, 1948), 193–194.