This feature is part of a series collaboration with the “50 for 50” project, an initiative of the North Carolina Arts Council in celebration of their 50th anniversary.

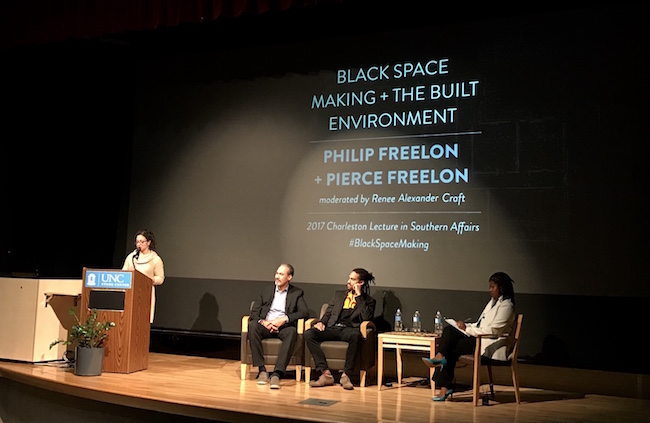

Phil Freelon, best known for leading the design team of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and his son Pierce Freelon, Durham-based hip-hop artist and professor, sit down to discuss how the arts define their family.

Pierce: My earliest memories of creativity would probably be conducting a play that I dreamed up about a kid who was in a tree [that] lightning struck. I must’ve been 3. I remember switching the light switch on and off to create the lightning effect and assembling the family for this theatrical production. I don’t know that I would have called that creativity at the time, but later in life I began to realize that was creative expression. I say that to say [creativity] was as much a part of our household as playing basketball in the yard. It was part of the fabric of our upbringing.

Creativity was as much a part of our household as playing basketball in the yard. It was part of the fabric of our upbringing.

Phil: It’s very similar for me. Arts were part of daily conversation and activities when I grew up in Philadelphia. My parents would take us to museums and exhibits and performances. My grandfather was a painter of some note during the Harlem Renaissance period. I particularly remember a moment when I was 6 or 7 with my grandfather, who had taken me for a walk through the woods. It was just him and me. He asked me to sit down and be quiet and close my eyes and listen to the environment. It was my first memory of being aware of my surroundings in a conscious way. As a professional designer and architect, that’s what I do for a living now, so it’s almost a direct connection back to my childhood.

In school, you figure out what you’re good at and what excites you. I was interested in drawing and sketching and painting, but I was good at math and I enjoyed the sciences, particularly geometry and physics. When I stumbled upon the design and drafting class in high school I said, “Wow, I can combine the artistic side and the technical side and maybe architecture would be a good thing.” Architecture turned out to be the right thing.

Pierce: I think mine started in school when I performed improv at Durham School of the Arts for the first time. It was amazing to me that I could work a room and have people laugh and react. There was this crazy exchange of energy that was really rich. I got to join the DSA Players—the top tier Durham School of the Arts theater troop—and I was the only 7th grader to get into the troop. To be acknowledged by my peers and teachers was affirming. I’m more into music now, but everything I’ve learned in theater is a part of every performance [and] every recording [I do].

Phil: I really enjoy the aspect of architecture that I’ve focused on my whole career: creating spaces for everyday people—whether it’s a bus station or the human services complex down the street where everyday people who may not be able to afford healthcare in the traditional way can go . . . or a school that’s open to the public. What’s at the root of this is the belief that everybody should be able to experience beauty in their environment, not just those who can afford to hire an architect to design a $2 million home or the business that can build up a sprawling corporate headquarters because they have the resources. [I think of] someone who bought a bus ticket to come here from New York and rode on the bus all night. When they get off that bus and come into the terminal, why shouldn’t that be as beautiful as the museum or as the corporate headquarters? That drives me because I think that public spaces can have an impact on how you feel, how you work, how you play, [and on] whether you’re comfortable or not in a space with other people, or alone, or in a hospital where there’s tremendous stress and anguish. That environment needs to be just as inviting and inclusive and beautiful as someone’s private home with artwork hanging in it.

What’s at the root of this is the belief that everybody should be able to experience beauty in their environment.

Pierce: I feel what Dad’s saying. One of my proudest moments has nothing to do with my art. It was being in D.C. at the opening of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture. That’s pride. That was beautiful. I think everyone has their own superpower, and our purpose on this planet is to identify what it is and to manifest it in its fullness. I think that’s something my dad has done. I mean Da Vinci, Imhotep . . . Phil Freelon. Maybe that sounds a little extreme. Imhotep did the pyramids in Egypt, but damn. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture will be around for centuries, and it is in the most powerful country in the world. [It’s] the landmark that is the birthright of black people in this country. That’s huge. It’s as significant for Americans as the Louvre is in France or any other structure of social cultural significance.

Phil: My proudest moments have to do with family. I’m living my proudest moments now as I see our children and grandchildren [grow]. I think Nneena would say the same thing. Watching Nneena’s career and knowing that we did it together and [that] she feels the same way about my career is just incredibly fulfilling. My career has been great, but those are the things that resonate with me.

Pierce: There are many things I’ve learned from my father, [but] the one that I’ll give is chess. Chess is a good metaphor for how you approach things with foresight and thoughtful, methodical precision. I’m more impulsive. We’ve been playing chess for 30 years, and I’ve only beat my dad once. The time that I beat him I was paying so much attention, and I was visualizing several moves ahead. I do think aspects of that have influenced the business side of my creative entrepreneurship. Dad is also a business man, so he’s not just in the office all day making sketches and doing the fun stuff. He also owns the building and cuts the check. He runs the business. That has always been a part of my observing you.

Phil: Well I’ve learned a lot from Pierce aside from the arts. Watching how he engages young people is really inspirational. I think he felt like he wanted to be an example and a leader from the time he was small. My father was in sales and marketing, so he had the outgoing personality. It was very natural to him as it is for Pierce to have that charisma. I remember looking up at my dad and thinking, “Gosh, am I ever going to be able to communicate with people like that?” A lot of my job is convincing clients that they ought to hire me to do these incredible things, and most of the time the client—whether it’s an institution or an individual or a CEO—is about to expend more financial resources than any other time in their lives, so you have to garner that confidence and build a relationship. I learned that from my dad, and I see similarities in Pierce’s personality. Folks are drawn to him. They can see integrity.

I feel like if I had a superpower it would be [that] I have an overabundance of love to give and share through my art. I feel like that’s part of my purpose on this planet.

Pierce: I came up surrounded by beauty and love [from] both my parents and my grandparents. I’ve been lucky to [be] surrounded by people who love me unconditionally. You can’t say [that’s] a human right, but it should be. I think my art is a manifestation of that love. I feel like if I had a superpower it would be [that] I have an overabundance of love to give and share through my art. I feel like that’s part of my purpose on this planet. It’s not like I have an unusual capacity out of nowhere . . . it’s because I was filled with it. There’s an abundance here, so I’m more than happy to pay that forward.

Phil: I love what you said about love. Because the more you give, the more there is. It isn’t a finite thing, and that’s what Pierce does. We’re so proud.

Learn more about the 50 for 50 project, an initiative of the North Carolina Arts Council, and stay tuned for more collaborations with Southern Cultures each month.