For the 10th anniversary of the BP Oil Spill and the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, we share Andy Horowitz’s 2014 article, which includes oral histories with those directly impacted by the environmental disaster around Empire, Louisiana. As resident Karen Hopkins told Horowitz in an interview, “Protect what you have while you have it and don’t be afraid to fight. Don’t be afraid to ask the questions, demand the truth. It doesn’t matter if you look like an idiot screaming in the street. If someone hears you, it’s worth it.”

Karen Hopkins lives in Grand Isle, Louisiana, where she manages Dean Blanchard Seafood, one of the largest seafood processors in the state. Before the BP oil spill of 2010, she recalled, “a typical day would be about five nervous breakdowns.” That is because Dean Blanchard typically bought between thirteen and fifteen million pounds of shrimp a year. For Hopkins, that meant:

You have three trans-vac suction machines working. You have three crews in three different staging areas unloading boats that are waiting in line, and you have three men coming in with shrimp tickets from three different boats at the same time, and you have people waiting in your office to get paid for their catch. The phones are ringing off the hook because you have fishermen who want pricing and . . . you have processors who are competing for your product and they’re trying to jack you out of some money because they’re trying to lower the price or they tell you that these shrimp weren’t pretty enough. You have to deal with them. And there’s only one of you.

Before the spill silenced the phones and emptied the office, turned off the suction machines and docked the boats, that was a typical day, and Karen Hopkins loved it.1

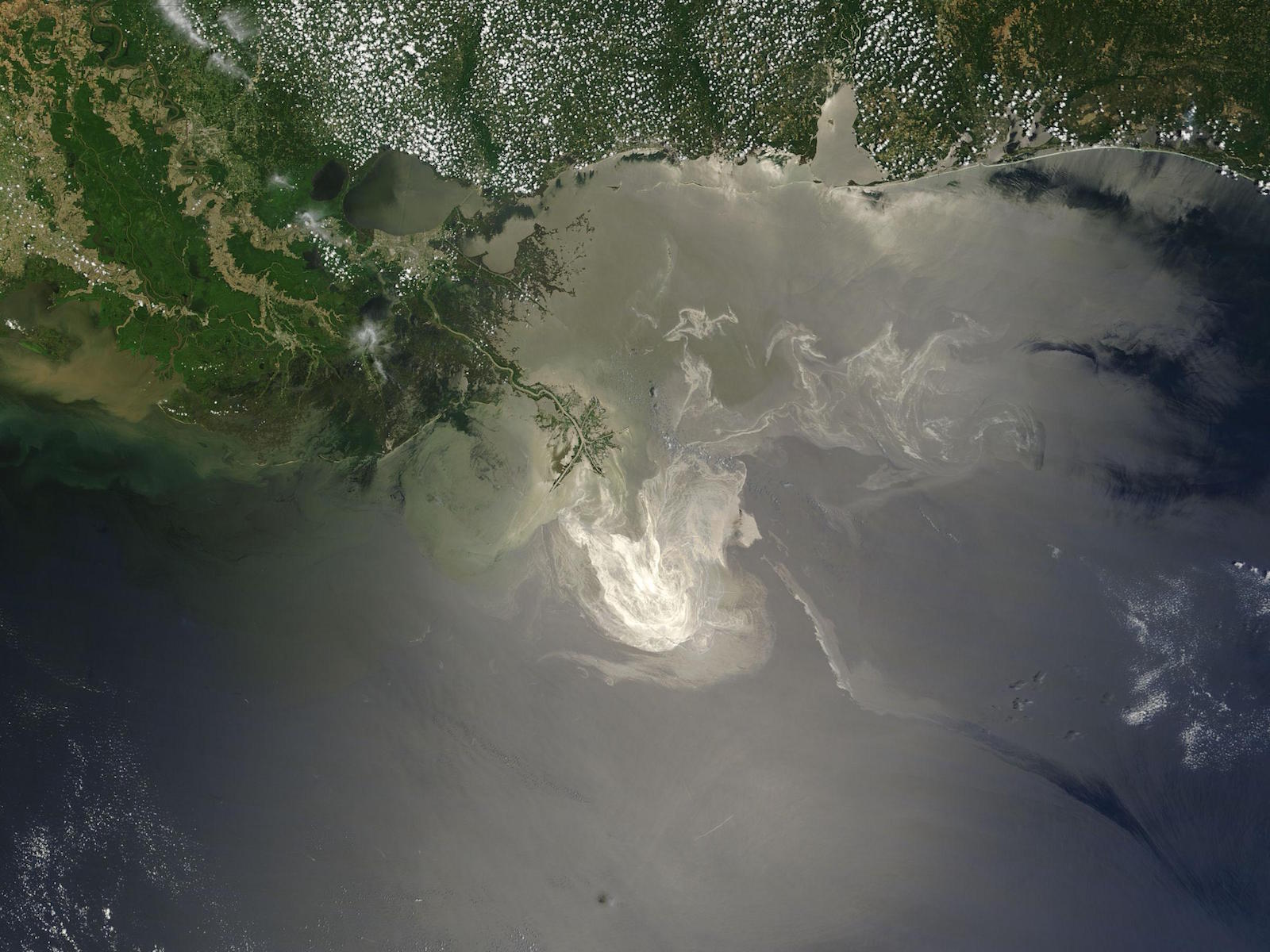

In the months after the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico, I conducted a series of interviews for the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina with people like Hopkins who live and work on the Louisiana coast. I asked them to describe their experiences during what President Barack Obama defined as “the worst environmental disaster America has ever faced.” That was more than four years ago. Now, most of the country has put behind them the grotesque images of oiled pelicans; the eighty-seven days the Macondo well spewed millions of gallons of oil into the Gulf, the spectacle broadcast live from 5,000 feet underwater, have faded from memory. On Magazine Street in New Orleans, people are lining up at Casamento’s for a dozen Gulf oysters on the half shell once again. Though in April 2013, a team of biologists from Louisiana State University detected hydrocarbons in the cocahoe minnow—an appetizer for the Gulf of Mexico’s food chain—and in June 2013, researchers discovered a 40,000-pound mat of tar just off the Louisiana coast, our temptation is to declare the disaster over. Historians, ironically, tend to have particularly short attention spans when it comes to disasters, often treating them as acute events that erupt in a catastrophic instant and fade away just as quickly.2

Yet accounts from the Louisiana coast—a place where recent history is so saturated with calamities that USA Today described the people there, in a headline, as living “forever in recovery”—compel us to reconsider what kind of disaster the oil spill is, how long it might last, and what, ultimately, might be most disastrous about it. Calling this disaster “the BP oil spill” conditions an inquirer to look for damage caused specifically by oil, and to measure its duration by the length of time that oil was allowed to spill. But listening to the people closest to the Gulf, it becomes clear that as much as this experience has been defined by an acute, chemical event, it also has come to represent a chronic, cultural trauma.3

For Hopkins, the shrimp tickets and the ringing phones were the stuff of everyday crises. Then there were the adversities that seemed to come once or twice a generation—hurricanes like Katrina, Rita, Camille, and Betsy that define generations on the Gulf Coast. Nobody wished for those terrible challenges, but Hopkins said it was clear how to handle them: you rebuild. “The people who live here,” she explained, “want to be able to fish and shrimp and play and love their families and fight against the storms and rebuild and do it all over again.”4

After Katrina, Hopkins’ Grand Isle, the alluvial sandbar 50 miles southwest of New Orleans as the pelican flies, was alive with the sound of hammer on nail. But after the Macondo well blew out, the island was deathly silent. Even the mosquitoes, Cherri Foytlin told me, had fled: “No mosquitoes, in Louisiana? How is that possible? You know the earth’s dead down here if there’s no mosquitoes.”5

Unlike a storm, the oil spill was what sociologist Kai Erikson ominously classified as a “new species of trouble”: a calamity brought on by human action, its trauma more chronic than acute, its poison insidiously working its way at once into “the tissues of the human body and the textures of human life.” On the coast, the oil spill came to embody what many described to me as a long struggle to sustain feelings of independence and stability in the face of an eroding ecological and cultural context. Increasingly, the place they helped create threatens to push them away.6

Grand Isle is a distinct place: “down the bayou,” as people there say, out past the end of the Bayou LaFourche’s muddy drift from Donaldsonville through Thibodaux and Cut Off and Golden Meadow, across 20 miles of angular bridges into the Gulf. A stretch of sand in the open water, Grand Isle is the barrier island for people farther inland; it receives the undiminished battering of any Gulf hurricane. Life there is so precarious that in 2003, journalist Jake Halpern wrote a chapter about Grand Isle in a book called Braving Home, which described “extreme locales” where one needed courage, daily, just to live there.7

Hopkins built her house out of cedar so that when it flooded, as it often did, it would emerge smelling good. Early in our interview, I asked Hopkins to describe what she saw when she looked out her window. I hoped that she might provide a quotation I could use later to evoke how her cedar house was perched directly over the Gulf. She could pull her boat right up to that window. This is what she answered:

The only thing I can say is that if the person who’s listening to this could close their eyes and just focus on the one word—freedom—and picture what freedom means to you—that’s what they would see when they look out of my window. They would see the sun setting every evening, and every evening, a different color. They would see, before this happened, the fishermen coming in every night with smiles on their faces. They’d come in every night with their wives waiting for them to pick them up off the boat, happy. And just a great sense of community, just the water and the air and the birds, my pelicans; this is freedom. It used to be. It used to be freedom. That’s what it means to me: freedom.

Hopkins turned my literal question about what she saw into a more important question about what that view meant to her. In doing so, she revealed how the environment around her—the sun, the water, and the birds—reflected back at her not just a physical reality, but a cultural and moral one. Reading her environment like a text, Hopkins transformed a mere location into a meaningful place. The Gulf had once made her feel free, happy, and independent. Now, since the spill, it confined her. “I’m very resentful,” she said. “[W]hen I told you about looking out my windows and seeing freedom, now when I look out of my windows I feel like I’m a prisoner that’s been wrongly convicted of a crime because we didn’t do anything wrong.” The sentence for the crime, Hopkins said, is death:

I’m terrified that this is going to be the death of the seafood industry along the Gulf Coast, and if the seafood industry dies, then the culture of our people is going to die with it. That’s my biggest fear . . . You can’t replace that. You can’t put a price on that—stealing someone’s dreams, and stealing someone’s heritage, and stealing someone’s life, and forcing them to make decisions that they shouldn’t ever have had to make in the first place. It’s hard to wake up every morning with a broken heart, and for the past three months, I have. I’ve woken up every morning with this grief.

To understand why Hopkins feared that the oil spill would kill not only the environment, but also the culture, one has to understand how the two are connected. On the coast, people’s sense of themselves is deeply imbued with their sense of place. Across Barataria Bay from Grand Isle, in Plaquemines Parish, Philip Simmons made that clear.8

When I met Simmons five years after Hurricane Katrina, he was rebuilding his house. He knew what he was doing. At sixty-eight years old, this was the third time he had rebuilt following a hurricane. He started by laying mudsills in the ground the way his great uncle Sid had taught him, salvaging the remains of a storm-tossed church for lumber. The mudsills braced pilings that lifted Simmons’s house up into the air, higher than ever before, compensating for water that rises higher and earth that sinks lower every year. The house now stands twenty-one feet above the ground. Sooner or later, Simmons knows, this house too will be flooded or blown down in a storm. For the time being, though, the new windows frame long views of the strip of land and marsh by the mouth of the Mississippi River where his family has lived and worked since the late eighteenth century. They came to this place when it was claimed by Spain, and remained as it was traded to France, bought by the United States, and taken, briefly, by the Confederacy. Mostly, though, Philip and his wife Gloria like to think of this place as their own. They hope to stay here, too, for as long as they can.

Simmons lives on the west bank of the river, but most of his ancestors going back two centuries, including his great uncle Sidney Johnson, were born on the east bank. The family was driven west by the 1915 hurricane that devastated the little communities across the river. In the mid-1920s, the Orleans Levee Board expropriated a vast section of the east bank for a “waste weir” flood outlet and blocked off the road to all the old towns. The 1927 Mississippi River Flood, and then hurricanes including Betsy, Camille, Carmen, Katrina, and Ike, took their turn washing away their remnants. Now there is almost nothing left to recall that the Simmonses, the Johnsons, or anybody else once lived on the east bank. But if you know where to go, down a narrow bayou towards a few remaining oak trees, you can still find Point Pleasant cemetery, where Uncle Sid, his brother Joe, their mother Anna Marie, and several dozen other relatives lie in an increasingly agitated rest.9

As he worked on his house, Simmons’s thoughts kept turning to Point Pleasant. Like many of the people buried there, Simmons has spent his life working closely with the land and water around him:

We lived off the land, pretty much . . . They fished oysters and shrimp and crabs, and trapped, and for many years they even hunted ducks and stuff—years ago when it was legal—for the market. Then they worked in the oil field. My dad worked for Freeport Sulphur Company. My old uncles built boats and had a shipyard and a sawmill. We used to cut wood and I used to go with one of them, Uncle Joe. We’d go up the Mississippi River. They had the big cypress trees [that] would come down with the big roots on them, and we used a passé-partout—the crosscut saw. We’d cut the roots off . . . Then he would use [the wood] . . . to repair boats or build boats . . . It was a good living and I trapped when I was a kid for fur, mink and otter, coon and nutria rats and stuff like that—muskrat. Then we fished oysters, by hand in those days with rakes . . . We had cattle, goats, pigs, chickens.

As Simmons describes, he and his family used the land. And in some cases, like the harvesting of cypress, oil, or sulphur, they took part in an economy that used it up. Scholars have a phrase for how economies built around the extraction of natural resources such as oil tend to work out for locals: they call it “the resource curse.” After decades of development, Louisiana has the highest concentration of petrochemical plants in the United States, as well as some of the highest rates of cancer. Oil companies like BP earn billions of dollars in profits, while Louisiana ranks third in the nation for the percentage of citizens who live below the poverty line.10

Nonetheless, Simmons’ uncles raised him to strive for a kind of balance. He evoked that principle when he recalled going fishing as a child:

When I was a kid you could take a white rag on a hook, go out there and throw it and pop the cork and catch speckled trout. That’s how good it was. You didn’t have to have no bait . . . Of course we didn’t waste it. We caught what we needed and if we caught more, we threw them back. We just caught what we needed, brought them home, and cooked them . . . You’d go back the next time and get you some more—keep it fresh. Whereas now some people, they want to go out there and kill them all, you know? So I think back then people kind of conservationed their own self. They wasn’t greedy and . . . they didn’t have all these big fancy restaurants and all that where they could sell them and make big money out of it either.

That “conservation your own self” ethic allowed Simmons to thrive in a hard place. The environment itself seemed to recognize that code, too, in his telling, rewarding his restraint with all the fish he needed, then punishing greed and waste with fewer fish. When Simmons says he lives off the land now, sitting in a house that hovers on pilings 21 feet in the air, the phrase takes on a new meaning: the land no longer supports him.11

Storms and rebuilding have defined the Simmons’ lives for a century; but in recent years, nature has felt more unsettling than in the past. “Hey, I can survive, I’m a survivor,” Philip Simmons told me. “You see that Survivor on TV? That ain’t nothing.” A visitor driving up to his house would think he was seeing Sanford and Son, Simmons said, “with all the junk and stuff I got.” Then he explained:

But I got cattle and I use tractors and stuff for that. I got machinery, I got bulldozers, I got a track hoe, I got four or five different tractors and bush hogs and an auger and all kind of equipment . . . [B]ecause that’s what I use to do a lot of the work. . . . Yeah, I’m a packrat, but you know I just—like these churches . . . The guy that was tearing it down was just going to destroy it. I said, “Man, look. That wood’s too good to just destroy. We don’t have any trees left now and we’re going to just keep throwing it away?”

The house Simmons is building now is constructed out of the wreckage, or the salvage, of a church whose congregation was unable to return after Katrina. It would be wrong to call him a scavenger, living off of the demise of others, but his adaption shows what it takes to survive in the context of a community that is disappearing around him.12

Simmons looks out his window and sees the world he knew slipping away. The fish that once seemed so plentiful that they would jump onto his bait-less hooks are gone. The cypress trees he worked at his uncle’s sawmill are gone. The churches are gone; Simmons helped tear them down. And as he looks out from his new kitchen window, where he once saw marsh, he now sees open water. The land itself is gone, eroding at the rate of a football field every hour, as it has for decades.13

Ironically, flood control is a major cause. Geologically speaking, floods built Louisiana. Every spring for millennia, the Mississippi River carried sediment to its delta. The river’s deposits during annual floods grew on each other like compound interest. Until the twentieth century, Louisiana grew. The river finished building the high ground under what became New Orleans’ French Quarter around 1400, more than a half-century after the French in Paris finished building Notre Dame. But once the Army Corps of Engineers completed the levee system, the Big Muddy’s mud—by design, to aid shippers—sailed straight out into the Gulf. Around 1930, when flood control was achieved, Louisiana started to shrink.14

At the same time, the discovery of oil transformed the marshes. Companies dredged hundreds of miles of canals through the coastal wetlands. The canals allow people, motorboats, and submersible drill barges to access offshore oil. The canals also allow salt water to access the marshes, killing the grasses and accelerating erosion. Nearly 2,000 square miles of coastal Louisiana have disappeared over the course of Simmons’ life there.15

Then came BP. After the Deepwater Horizon exploded on April 20, 2010, the Army Corps opened all the locks around the mouth of the Mississippi, hoping the river’s current would push the oil away from shore. The oil would have poisoned Simmons’s oysters and killed the grass his cattle eat. Instead, the river’s fresh water killed his oysters and flooded the cemetery—land that already had been subsiding for decades. When Simmons ferried me across the river to visit the cemetery that summer, he opted to stay in his boat and told me to take care as I got out and walked around in the mud. The flooding had unearthed bones. Barring an unprecedented intervention, in the coming years, the remains of the Simmons family will be washed into the Gulf of Mexico.16

When Simmons considered Point Pleasant Cemetery and the region around it, he perceived a place caught between two great, distant powers. The first was a federal bureaucracy that was too big to worry about local problems, harming while trying to help. The other was a multinational corporation—the community’s economic lifeblood—guilty of terrible negligence. To neither did he have any recourse. “There’s no common sense, is what I figure,” he said. The last memorials to Point Pleasant’s long history are eroding. The land itself is falling apart.17

The house that Simmons is rebuilding is sixty-five miles downriver from New Orleans, about halfway between the towns of Triumph and Port Sulphur in a community called Empire. Philip Simmons is living at the end of Empire. From afar, it may seem obvious that BP caused the BP oil spill, but on the coast, nobody I interviewed strongly criticized the oil industry. “From time to time there are going to be things that occur that are acts of God that cannot be prevented,” Texas Governor Rick Perry said of the spill. Calling a calamity a natural disaster is a way of excluding its causes from the realm of human culpability. “There was a degree of human negligence and greed” that caused the explosion, Hopkins told me at one point, “but it was an accident. No one meant for eleven people to die.”18

It is terribly difficult to come to terms with the ways you might be complicit with processes that threaten to destroy your place in the world. I asked Simmons who was at fault for the erosion that threatened his home. “Mother Nature, I guess,” he answered quickly. Then he thought about it some more. “I guess you could call humans part of it,” he allowed. Hopkins estimated that two-thirds of the people on Grand Isle work in the fishing industry, and a third work in the oil field. “If you don’t have a [fishing] boat here,” she said, “you work in the oil field.” Acy Cooper of Venice, Louisiana, a shrimper like his father and his son, said that fishermen and the oil industry “work hand in hand.”19

The people I talked to on the coast focused their frustration on the government. Cherri Foytlin moved to Louisiana from Oklahoma when her husband got a job working on an offshore rig in 2005, right after Katrina. “I was probably the only person trying to get into Louisiana when everybody else was getting out,” she said, accounting for why she was more optimistic than her neighbors when the spill first began. She soon became disillusioned:

I definitely used to think that the government would be there to take care of you. I really did. I thought if something horrible happened that they would come in and they would help you out with a kind heart and make sure that everything was taken care of, and that’s just not the case. I feel like right now we’re a big political ploy to get something else done, to get green energy in, which I’m all for, but I’m just saying maybe it’s not the focus right now. Maybe the focus might be capping the well and taking care of the people and the wildlife, but that’s just me. I’m nobody. But definitely I lost all faith in the government.

Distrust of the federal government is an old story for many white southerners. Still, most people I talked with joined Foytlin in situating their opinions about the government in recent history. The past still mattered, but their Katrina experiences were sufficient to stand for or encompass much older beliefs. Recovery from Katrina, they said, was harder than the disaster of the storm—harder because the challenges other people presented to them, in the form of government regulations, seemed more difficult, or more inscrutable, than the challenges the wind and water had posed directly. Simmons told me his breaking point was when he tried to get a permit for the house he built after Katrina:

[My wife] didn’t want me to rebuild this time because we had this trailer, but I felt like, hey, I don’t trust FEMA. They might come back and say, hey, we’re going to take the trailer. So I started . . . building this [house] . . . First of I went to see about a permit. They said you can’t build a house without an architect. I said, okay, I want to put a roof over my trailer. So I drove the pilings, put the mudsills in, I took this old house down, I put the floor up there, and then I started putting the walls up. Well, that was a mistake because then they come and say, hey, this is not a roof over your trailer; this is a house. I said, well, I went to see about a permit for a house and you said I had to have an architect, and I don’t think I need an architect. We went round and round and they actually cut my electricity off where I’m living here—took the meter and cut it off at the pole . . . because of FEMA regulations, so they say. I got on the phone and I called the parish president and I told him you better get my electric going. I’m losing my groceries and if I lose my groceries there’s going to be a killing in Empire. I didn’t name no names, but I meant business. When they come to cut the electric on the next morning, I was sitting on my porch with a shotgun and that guy said, “Man, don’t shoot me. I’m just following orders.” I knew the guy, and I wasn’t going to shoot nobody, but I was mad, I’ll tell you. Let me do what I got to do on my own property. You can’t build a house on your own property? What is the matter with this country? Where’s our freedom of choice? It just doesn’t seem right. They can tell me what I can do and what I can’t, but I’m paying taxes every year on it. I bought the land and it don’t belong to me? I pay for it every year. I just don’t think it’s right.

“What is the matter with this country?” Simmons asked. The question is a common one in contemporary America across the political spectrum. To assert that something is wrong with the country does not take personal responsibility, necessarily, but neither does it curse the heavens or bad luck for misfortune: it says that people, somewhere, are responsible. It says that what some call “acts of god” are deeply embedded in the acts of men.20

The oil spill, as the President said, is an environmental disaster. The spill killed pelicans and dolphins and sea turtles and shrimp and wetlands that might protect the coast from storm surges. There are lawsuits working their way through the courts that point to a lingering, even growing, toll on human health caused by the oil and the chemicals BP used against the Environmental Protection Agency’s instructions to disperse it. The explosion of the Deepwater Horizon killed eleven people, but the disaster’s casualty count may not yet be closed.

Many of the oil spill’s consequences, though, will escape the quantification of environmental impact assessments. Silencing work along the coast, making people fear that the food they eat is poisoned, that their very bodies may be poisoned, and that they have no recourse to the industry that caused the harm or the government that was supposed to protect them from it, instilling the quiet dread that they may somehow share in the blame for all of this: these lessons will be difficult to unlearn and their costs will be hard to measure. Nonetheless, they have tarnished the coast as much as any oil sheen or tar ball.

The oil spill ruptured ways of life that have brought sustenance and meaning to people for as long as they can remember. Rosina Philippe, an Atakapa-Ishak Indian, told me that oral tradition—as well as carbon dating of burial mounds— suggests that her community has been fishing in south Louisiana for thousands of years. Now, however, they are scared the fish are not safe to eat. Though they do not look as far back, Philip Simmons, Karen Hopkins, and others in south Louisiana disproportionately come from families that have stayed in the same place for generations, engaging in work and folkways that connect them with the local past. They think of themselves as participating in a way of life that is old and continuous. That connection imbues the stuff of daily life with significance.

But now, instability feels like the nature of life—on the Louisiana coast and beyond. To try to quantify the costs of that unsettling feeling, or to think that its effects can be bound in time, is to mistake a home for a house and a place for a location. In 1976, Kai Erikson wrote, “people who live out on the margins of the new America, who continue to live in communities and to think of themselves as folk, are likely to experience the world we are making for them as yet another disaster.” That disaster cannot be broadcast on a streaming video feed. No “junkshot” can attempt to plug up aloof federal policy, reckless extractive industry, global environmental change, and all of the stuff that folklorist Alan Lomax called cultural “grey-out” and the economist Joseph Schumpeter described as “the perennial gale of creative destruction.” Schumpeter thought of “perennial gale” as a metaphor, but in Louisiana, it sounds like a reference to hurricane season. “Incessantly revolutioniz[ing] the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction,” Schumpeter wrote, “is the essential fact about capitalism.” Or, as Karl Marx put it, “all that is solid melts into air.” Had he been from Louisiana, Marx might have written, “washes into the sea.” In April 2013, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration removed Yellow Cotton Bay, Bayou Jacquin, and twenty-nine other Plaquemines Parish place names from the official government map; they no longer exist.21

On the Louisiana coast, the oil spill’s most profound threat may be how it heralds that there will come a time when you cannot go home again. Years after BP capped the Macondo well, the trauma lingers. Thus, true recovery must involve more than booms, or nets, or chemical dispersants; it cannot be measured in parts per million alone. An essential gauge will be the report on the view from Philip Simmons’ and Karen Hopkins’ windows.22

As the cliché goes, “Every cloud has its silver lining.” Particularly in American accounts of disasters, it is traditional to conclude with a happy ending: progress triumphs. But those conclusions are difficult for me to reach here. “We are survivors, in this age,” Saul Bellow’s Herzog writes, “so theories of progress ill become us, because we are intimately acquainted with the costs.” I turn to Karen Hopkins:

What I want to say today is this catastrophe, this crime, this destruction of our ecosystem, the negligence by the federal government for years of helping us to restore our coastlines, the government and the oil companies taking and taking and taking from the Gulf Coast all these years and not putting back, this is, I believe, the culmination of all those sins . . . I hope that one day it will heal itself, but I don’t believe that I’ll ever see it the way that it was before this in my lifetime. I really don’t. I would encourage everyone to look for pictures of Grand Isle and remember it the way that it should have been, the way that it was before offshore drilling really started here and the erosions of our coastlines, our barrier islands—the destruction of those. This place was covered with huge oak trees. It was a paradise, and it still was a paradise before this, but I feel like it’s over now and the worst has yet to come. This is just the beginning, even three months into this. Protect what you have while you have it and don’t be afraid to fight. Don’t be afraid to ask the questions, demand the truth. It doesn’t matter if you look like an idiot screaming in the street. If someone hears you, it’s worth it.

I told Hopkins that hers was a very powerful message, and asked her if there was anything else that she wanted to add to our interview. “Hopefully my grandchildren, my great grandchildren, if you say [this interview] will be in there archived forever, then they’ll have a stronger sense of who I am and who I was after I’m gone,” she said. I offered to send her a copy of the recording for her four grandchildren and asked if she wanted to add a message for them. “Ma maw loves you very much,” she told them, “and I hope you still have Grand Isle after I’m gone.”23

This essay first appeared in the Southern Waters Issue (vol. 20, no. 3: Fall 2014).

Andy Horowitz is Assistant Professor of History at Tulane University, where he specializes in modern American urban, environmental, and Southern history. He has collaborated with the Center for the Study of the American South for nearly two decades, beginning as a college intern with the Southern Oral History Program in 2002; he has since worked with the SOHP on a project about Katrina called “Imagining New Orleans,” and a project about the BP oil spill, from which the interviews in this article are drawn. His writing also has appeared in the Journal of Southern History, Historical Reflections, the Washington Post, and the New York Times. In July, Harvard University Press will publish his first book, Katrina: A History, 1915–2015. Horowitz is also guest editor of the forthcoming Human/Nature Issue (Spring 2021) of Southern Cultures.NOTES

The Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina, under whose auspices I embarked on this project, provides access to the full transcripts and audio of these interviews online. I am grateful to Jacquelyn Dowd Hall and the staff of the SOHP for their ongoing support of my work. I am grateful as well to Kai Erikson, Glenda Gilmore, Doug Kysar, Kate Dudley, Ruthie Yow, Talya Zemach-Bersin, and members of the Louisiana Folklore Society, the Yale Student Environmental Coalition, and the Yale Ethnography and Oral History Working Group for their enormously helpful comments on drafts of this essay.

- Karen Hopkins, interview by Andy Horowitz, July 13, 2010, interview R-0495, transcript, 19, Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (henceforth referred to as SOHP Collection).

- Barack Obama, “Remarks by the President to the Nation on the BP Oil Spill,” June 15, 2010, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-nation-bp-oil-spill; National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling (Washington, D.C., 2011); Historians of disasters have tended to write what Lawrence Powell calls “instant history.” See Powell, “What Does American History Tell Us about Katrina and Vice Versa?” Journal of American History 94 (December 2007): 876.

- Rick Jervis, “In the Gulf: Lives Forever in Recovery,” USA Today, June 18, 2010.

- Hopkins, July 13, 2010, 13–14.

- Cherri Foytlin, interview by Andy Horowitz, July 6, 2010, interview R-0494, transcript, 15, SOHP Collection.

- Kai Erikson, A New Species of Trouble: The Human Experience of Modern Disasters (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1994), 20.

- Jake Halpern, Braving Home: Dispatches from the Underwater Town, the Lava-Side Inn, and Other Extreme Locales (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003), 168–210.

- Hopkins, July 13, 2010, 12; “The first thing that makes oral history different,” Alessandro Portelli has written, “is that it tells us less about events than about their meaning.” Portelli, The Death of Luigi Trastulli and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History (New York: State University of New York Press, 1991), 50; “With words,” Keith H. Basso suggests, a “physical presence” can be “fashioned into a meaningful human universe.” Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 40; Hopkins, July 13, 2010, 30; Ibid.

- Board of Levee Commissioners, Orleans Levee District, “Report of Levee Examining Committee, Plaquemines Parish East Bank Levee District” (New Orleans, 1926), accessed in the Louisiana State Archives, Baton Rouge, LA. The Cemetery is “on the left bank of the Mississippi River, at a distance of about Sixty-five miles below the City of New Orleans.” See “Act of Donation by Narcise Cosse, Sr. to Board of Trustees for the Point Pleasant Cemetery,” July 23, 1921, copy in author’s possession.

- Philip Simmons, interview by Andy Horowitz, July 12, 2010, interview R-0498, transcript, 2–3, SOHP Collection; Richard M. Auty, Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis (New York: Routledge, 1993); Terry Lynn Karl, The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); See F. D. Groves, et al., “Is there a ‘cancer corridor’ in Louisiana?” Journal of the Louisiana Medical Society 48 (April 1996): 155–165; Barbara Allen, Uneasy Alchemy: Citizens and Experts in Louisiana’s Chemical Corridor Disputes (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2003); United States Census Bureau, “Number and Percentage of People in Poverty in the Past 12 Months By State and Puerto Rico: 2010 and 2011,” 3, http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/acsbr11-01.pdf.

- Simmons, July 12, 2010, 10–11.

- Ibid., 17; Ibid., 12.

- Brady R. Couvillion, et al., “Land Area Change in Coastal Louisiana from 1932 to 2010,” U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3164 (United States Geological Survey, 2011), 1.

- John M. Barry, Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998); Richard Campanella, Geographies of New Orleans: Urban Fabrics Before the Storm (Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2006); Richard T. Saucier, Recent Geomorphic History of the Pontchartrain Basin (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963).

- Between 1884 and 2002, “the long-term average erosion rates for the Plaquemines barrier shoreline were –23.1 feet per year.” See Shea Penland, et al., “Changes in Louisiana’s Shoreline: 1855–2002,” Journal of Coastal Research 44 (Spring 2005): 33.

- “State, Corps consider opening Bonnet Carre Spillway to keep Gulf oil spill at bay,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 5, 2010, http://www.nola.com/news/gulf-oil-spill/index.ssf/2010/05/state_corps_consider_opening_b.html.

- Simmons, July 12, 2010, 16.

- Jake Sherman, “Rick Perry: Oil spill may be ‘act of god,’” Politico, May 3, 2010, http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0510/36691.html; Ted Steinberg, Acts of God: The Unnatural History of Natural Disaster in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Hopkins, July 13, 2010, 25.

- Simmons, July 12, 2010, 15; Hopkins, July 13, 2010, 24; Acy Cooper, interview by Andy Horowitz, July 20, 2010, interview R-0493, transcript, 6, SOHP Collection.

- Foytlin, July 6, 2010, 21–22; Foytlin is Native American, and Native Americans’ history gives them plenty of reason to distrust the federal government, too. On how white southerners long “despised concentrated power,” see William Link, The Paradox of Southern Progressivism, 1880–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 3; Simmons, July 12, 2010, 36–37.

- Kai T. Erikson, Everything in Its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976), 256–259; Alan Lomax, “An Appeal for Cultural Equity” (1972). Reprinted in Ronald D. Cohen, ed., Alan Lomax: Selected Writings, 1934–1997 (New York: Routledge, 2003), 285; Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism & Democracy (1942; George Allen & Unwin, 1976), 83; Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848; Brooklyn Verso, 2012), 38; Amy Wold, “Washed Away,” The [Baton Rouge] Advocate, April 29, 2013, http://theadvocate.com/home/5782941-125/washed-away.

- The historian must be aware that nearly every generation in American history has perceived a decline in community cohesion. See Thomas Bender, Community and Social Change in America (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1978).

- “What has most distinguished American responses to destruction over the past three centuries or so,” writes Kevin Rozario, “is the widespread conviction, born of beliefs and experience, that calamities are instruments of progress.” Rozario, The Culture of Calamity: Disaster and the Making of Modern America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 20; Saul Bellow, Herzog (1964; New York: Penguin Classics edition, 2003), 83; Hopkins, July 13, 2010, 37–39.