Murray Bridges, the proprietor of Endurance Seafood, was in his sock feet. He was sitting on a burgundy recliner in the den of his brick ranch house in Colington, North Carolina, near Kill Devil Hills on the Outer Banks. Bridges, now in his mid-eighties, specializes in soft-shell crabs, but he wasn’t working on the water that day. He was able to receive visitors on this mid-April afternoon in 2016 because a nor’easter was pummeling the pollen-laden pines and blooming dogwoods outside. The sun was bright and the sky was crystalline blue, but the temperature was in the low fifties. Roanoke Sound was roiling with white caps all the way back to Mann’s Harbor, on the mainland.

“We always get excited a little bit too early,” Bridges said, in his Outer Banks brogue that made excited sound like “exsoited.” “I set out pots to catch peelers a couple days ago, but if we have any in there, they won’t be shedding now.” He was referring to the coming season for soft-shell crabs, or “peelers” in the local parlance.1

Photographer Donna Campbell and I had come to the coast to witness the annual ritual of harvesting soft-shell crabs. This, our first visit to Endurance Seafood, was part of a year-long project to document local traditions that have developed around a dozen native foods—including scuppernongs, ramps, shad, and oysters—that help to define North Carolina’s culture and culinary history.2

Usually in early May, North Carolina’s blue crab population begins molting. These crustaceans—Callinectes sapidus, two Latin words meaning “beautiful swimmer” and “tasty”—outgrow their shells many times during their lives. When the molting process starts, the crabs help it along by taking additional seawater into their bodies so that eventually their shells crack. Then they slip slowly out of their old armor and begin at once to grow new, larger exoskeletons. In this soft-shell phase, the crabs are considered a delicacy. In many Asian kitchens, they will be prepared as sushi. In kitchens that serve traditional North Carolinian fare, soft-shell crabs are more likely to be pan-seared or breaded and deep-fried.

Fresh or Fried: A Southern Cultures Seafood Reader

Twelve fish(ish) tales from the archives (with accompaniments). Read the whole platter here.

In a report published in 1985 from a national symposium on blue crab, experts admitted that they weren’t quite sure when the soft-shell blue crab was first harvested and sold commercially in North Carolina, but landings of the creatures are recorded as far back as 1897. In the biennial report of the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development from 1937, the government stated that Carteret County was the only place south of Virginia that produced soft-shell crabs in quantity, employing “significant numbers of people during the months of April and May.” Most of the crabs harvested in those days were sold to vendors in Maryland. According to Bridges, the soft-shell business really didn’t begin to scale up in North Carolina until some forty years ago.3

These days, North Carolina soft-shell crabs appear on menus statewide. Harvesting and shipping techniques have grown much more sophisticated. For a long time, only coastal folk bothered to seize the moment of the crab’s transformation and make a sandwich of it. Bridges said that people used to run across soft-shells in their crab pots or find them in the shallows and bring them home for dinner. Murray Bridges’s wife, Brady, said that when she was a girl growing up in Colington, she would sometimes kick soft-shells out of the seagrass and sell them to Old Nags Head cottagers. But North Carolinians didn’t catch them in quantity until Bridges and others learned that their counterparts in Virginia and Maryland were turning an especially handsome profit on soft-shells in the month of May—normally a slow period in the seafood cycle, when fishermen are waiting for the shrimping season to begin.

“I learned about soft-shells from the government’s Sea Grant program,” Bridges said. “They were going round to different communities to show fishermen better ways of doing things. I went to meetings, and I even went up to Virginia and Maryland to see how they’d come up with this method for shedding crabs. I seen where it was a good thing. Price-wise, too. They could sell a soft-shell for three times what we’d get at the local market.”

Bridges was raised in Wanchese, at the southern tip of Roanoke Island, and spent more than twenty years on the water as a merchant marine. He settled down with Brady in her hometown of Colington, which sits near the convergence of Currituck, Albemarle, Croatan, and Roanoke Sounds—the perfect site to launch a seafood business.

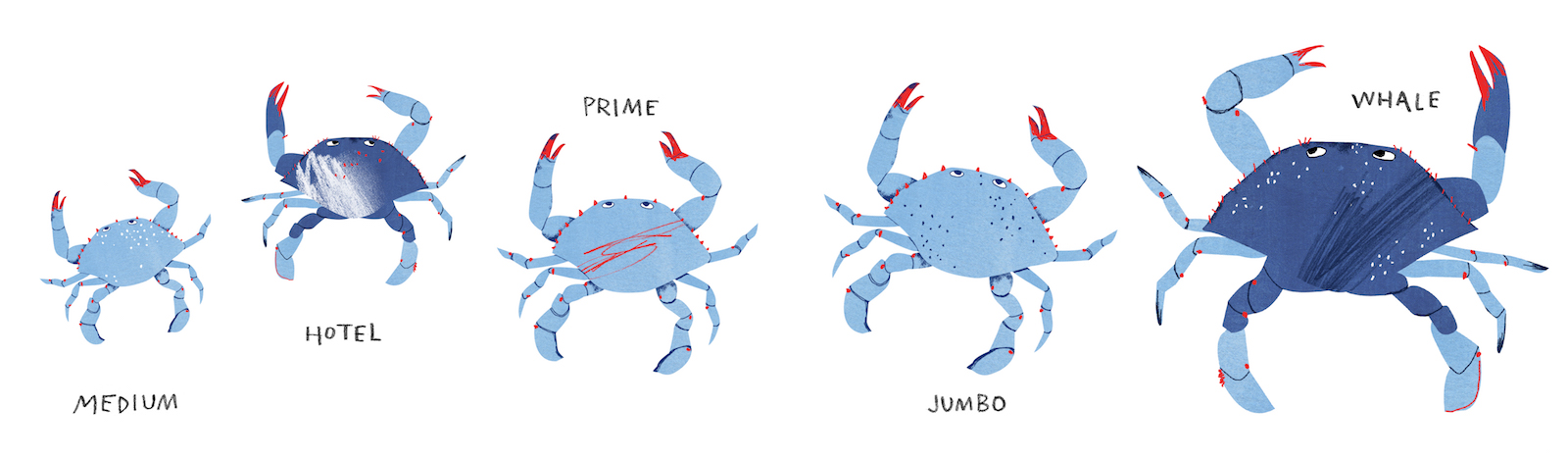

Bridges learned about grading soft-shell crabs according to size, which is a different system from grading hard-shell crabs. When he began, the very smallest crab was called, curiously, a “medium,” a term that is still used, though the smallest crabs are not generally favored by the buying public in the United States today. Four additional categories, each increasing in size, are hotels, primes, jumbos, and whales. Initially, only male crabs could be classified as whales; the largest females could only be placed in the jumbo category. “That was the way they graded up north,” Bridges said, shaking his head, “so we had to follow that until the number of males fell off. Now females can be graded as whales, too. Go figure.”4

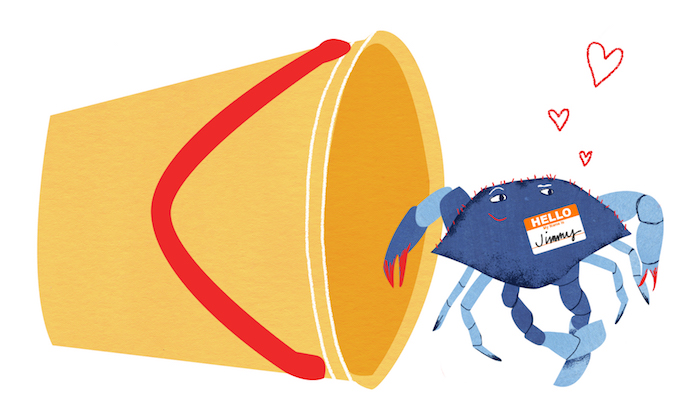

Bridges devised special crab pots, smaller than the traps used for blue crabs the rest of the year. During soft-shell season, he puts a small male crab—known as a “jimmy”—inside these smaller pots for bait. “We don’t use a big rusty crab for bait. A little jimmy’s got the stuff,” said Bridges, grinning. Because molting occurs during the mating season, the traps lure hundreds of females, and then males follow them into the traps. Mating happens immediately after the female has shed. Once caught, these peeler crabs are placed in tanks, called shedders, for a few hours—only long enough to finish molting and to firm up enough to be handled for shipping. After a crab has shed its old shell, its new, larger shell will harden in a mere twenty-four hours if the crab stays in the water. A live soft-shell must therefore be taken out of the water and sent to market very quickly, or it may be cleaned and frozen.

In the early years, Bridges scaled up his operation with float shedders—tanks that actually rode on the surface of the creek behind his house. They were rigged to circulate water as the crabs inside began to shed their shells. But the process was cumbersome. “We try to bring them into the tanks just before they start shedding,” Bridges said. “When they first shed, though, they’re too soft to work with. We have to wait a bit before they’re ready to be handled. They need to firm up so they can live for at least two or three more days after we ship them. But if you keep them too long in the shedder, they’ll weaken and die.” Bringing the peelers to shore once they had shed was also tricky.

Bridges has since come up with creative alternatives to this set-up. “One night I went out to check on my peelers and got tangled up and fell in the shedder!” he said, chuckling. “Right then and there I decided I was going to do better, and I came home and fixed me six or seven shedder tanks on solid ground with electric lights strung up so I could watch them at night.”

As his soft-shell business grew, Bridges eventually built by hand 150 four-by-eight-foot tanks. They are lined up outside the processing warehouse that flanks his ranch house. Each is outfitted with overhead lights. A complex grid of white pvc pipes is connected underneath the wooden and fiberglass tanks to carry water pumped from the creek to overhead spigots that shower the crabs and freshen the water. The water pressure can be adjusted above each shedder. Drains in the bottom of each tub circulate the water back out into the creek on the other side of Bridges’s spit of land. Moving water provides the molting crabs with oxygen.

Bridges still sets his own crab pots and buys thousands of additional peelers from many of the other ninety-some Dare County crabbers who have shedding permits. He was among the first to master the technique of properly packing and shipping the crabs to maximize their freshness. When the creatures reach the best possible moment after molting, they are carefully packed in waxed cardboard cartons, layered with parchment paper and a scrim of ice on top. Depending on the grade, the cartons hold seven-and-a-half dozen to fifteen dozen per box. At the peak of the season, which usually lasts a week to ten days, six members of the Bridges family will work day and night monitoring the water temperature and the condition of every single crab, which sheds on its own timetable.

At the peak, the family handles 4,000 to 5,000 dozen crabs per day. Their record shipment of crabs at one time, said Bridges, was fifteen pallets. A single pallet holds 216 dozen. The quick math on that figure translates to a little more than 38,800 crabs processed by hand in a single day.

“My daughter, Kissy, gets all hepped up this time of year,” said Bridges. “Once we’re into it, though, it gets a little rough. We don’t get much rest or eat regular.”

It takes a seven-figure credit line and the seasoned eyes of the Bridges family team to pick and purchase the peelers that are within days of molting. Murray Bridges explains that the telltale sign is on a crab’s back paddlers, where a fine white line runs along the little hairs at the end of a section of leg. “That line will go from white to pink to blood red when the time comes,” Bridges said. He pulled a blue crab out of the cooler and pointed at the spot.

Though some crabbers will show up to his dock with their day’s catch hoping to pass off peelers that are far from shedding, Bridges can always discern the degree of readiness. “And we don’t let the crabbers grade their catch,” he said. ” We do it ourselves.”

Even before the crabs start shedding in earnest, Bridges and his competitors watch the weather and their traps intently. He said that the fishermen will get “clam-lipped”—unwilling to reveal how big their catches are—as the race to collect peelers draws near. In his warehouse on this day, more than 2,000 waxed boxes have been assembled and stacked, at the ready. Out in the yard, some of the thousand peeler pots that Bridges’s daughter, Kristina—known since childhood as Kissy—has made in the off-season are waiting to be deployed.

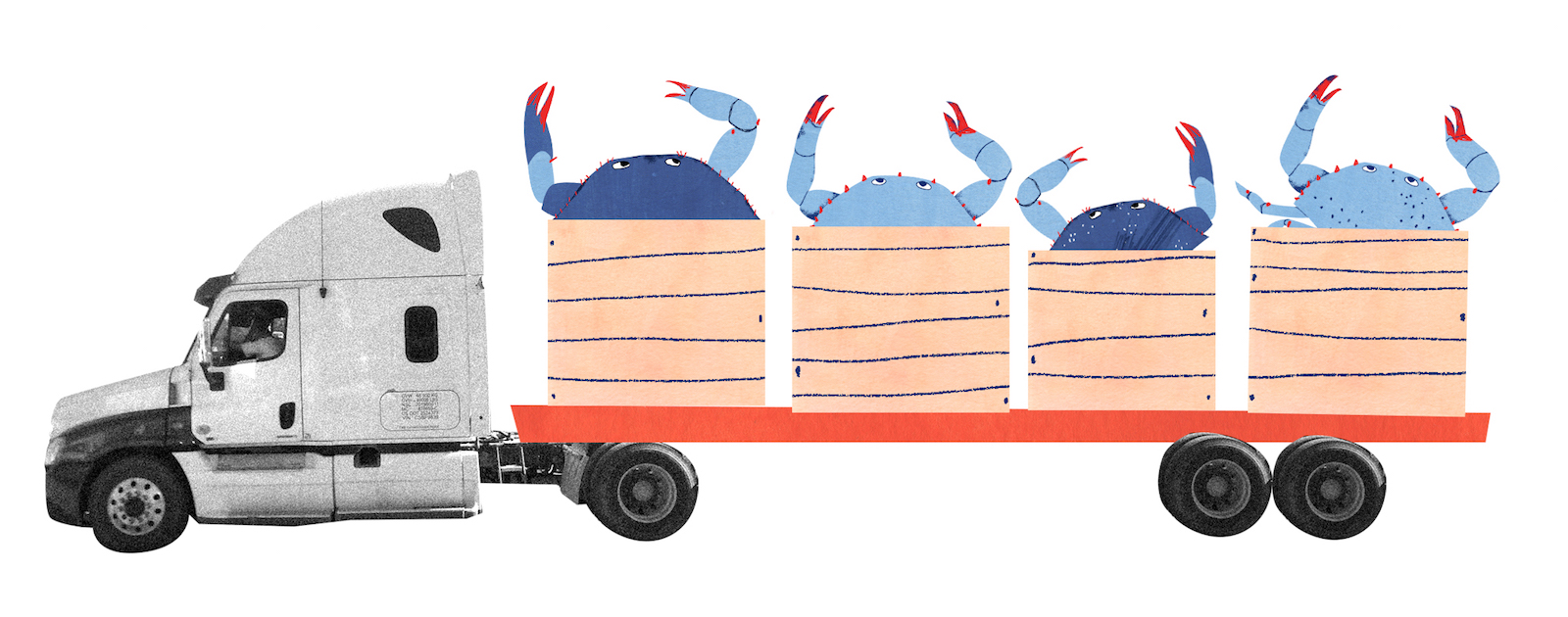

Though he sells some of his catch locally and some of it to a couple of markets in Japan, most of Bridges’s soft-shell crabs leave his operation packed in tractor-trailer trucks that travel up the East Coast. The bulk of his live crabs end up at the famous Fulton Fish Market, which operated from 1822 to 2005 in Manhattan and now is at Hunt’s Point in the Bronx. If there is a glut of crabs at a certain point in the season, Bridges might also send some to Handy International in Crisfield, Maryland, the largest crab processor in the world. At Handy, one hundred-some employees clean crabs around the clock and then freeze them. While soft-shell crabs are prized because diners don’t have to pick the sweet meat out of the claws and shells and can instead eat the body whole, it is still necessary to remove the mouth, eyes, gills, and abdomen in the cleaning process.

Bridges said negotiating price is among the most stressful parts of his business. Kissy generally handles that. He said:

Sometimes, they’ll call us up from New York and say, ‘We can only pay you ten dollars a dozen for these soft-shells.’ They take them on consignment, see, and we might be thinking we’d get thirty dollars a dozen when they try to give us ten. Or they’ll say, ‘Half your crabs are dead.’ We have no way of knowing if they are trying to cheat us! They can get so many crabs coming into the market up there that they’ll cut the price right out from under you.

Once, Bridges rode the freight truck all the way up to the market to see the situation for himself. For most of the past century, the Fulton Fish Market was known to be influenced by one or more Mafia families at a time. Federal officials brought racketeering charges against the operation, and the charges were upheld in 2001. Now, the City of New York regulates the business. More than a billion dollars’ worth of seafood comes through the new location at Hunt’s Point these days, making it the second largest seafood market in the world, surpassed only by Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market.5

A younger generation of crabbers has moved into the soft-shell business. This generation has benefitted from Murray Bridges’s experience selling product to national wholesalers, and packing and shipping live soft-shells to these vendors.

Feather and Willy Phillips, longtime friends of the Bridges family, own Full Circle Crab in Columbia, North Carolina, an hour’s drive inland from Endurance Seafood. In the early years of their shedding operation, Willy, who is almost twenty years younger than Murray Bridges, would go out to check his pots while Feather stayed home with their young son, Jake. Feather monitored the shedders at their homestead at Old Fort Landing, on the Alligator River in Tyrrell County. She has witnessed the seasonal vigilance and tension build among crabbers for decades now. There is no set date for the start of soft-shell season. It all depends on the moon, tides, and water temperature. I have talked to Feather and Willy many times about their operation.

“When honeysuckle sweetness fills the air, the shedders will be full,” Feather said definitively. “Some crabbers here use potato plants, watching for the flowers as the sign. Of course, the full moon is always a sign, too.”6

As it turned out, a full moon came toward the end of April and put all the crabbers on high alert. “It seems like the molting usually starts about a week before the full moon in May, but the April moon was so late this year,” Bridges told us. “75 percent of all the soft crabs we harvest will usually come in May, not April.” But the mysteries of nature keep fishing families guessing.

Willy Phillips was four years old when he first saw battalions of small fiddler crabs coming out of the salt marsh and marching toward his childhood home on Hewlett’s Creek in New Hanover County. Those crabs were not responding to the moon, however. They began climbing the exterior walls of his parents’ house to find purchase on the roof. In that fall of 1954, long before Doppler radar and sophisticated weather prediction was possible, the surge of crustacean refugees was the only sign the Phillips family had that Hurricane Hazel was barreling toward Wilmington.

Sixty years later, Phillips represents the generation behind his mentor, Murray Bridges. He sells many thousands of soft-shell crabs each year through his wholesale and retail seafood market on U.S. Highway 64 in Tyrrell County.

Phillips speaks passionately about the current state of the soft-shell crab harvest in North Carolina’s northernmost waters of the Albemarle Sound and the challenges created by global economic forces and environmental degradation:

The blue crab sheds thirty-two to thirty-seven times during its lifetime. They shed all summer long and are the bedrock of our ecosystem here, which is the second largest lagoon system in the country. The soft-shell crabs are helpless when they shed, so they are food for trout, flounder, croakers, spot, red drum, striped bass—all the other seafood that we harvest. Beyond their importance to us, they are essential to the health of the whole system.7

I called Willy with a few follow-up questions after our April visit with Murray Bridges. He talked to me on the phone from his retail seafood shop. It was 8:30 in the morning, and he had been up for hours. This was his busiest season. He stopped the interview midsentence and apologized for the sudden interruption. He put down the phone, but I could hear him talking to someone who was about to leave the store: “No, no charge. I don’t want you to pay me for anything. That’s for Miss Libby. You tell her that’s for all the years she’s been buying my crabs and making my crab pots.”

Phillips’s retail store is small compared to the massive coolers and the spread of shedders that stretch out back, under the roof of his Butler building, behind the storefront. His is one of the largest businesses in Columbia (population 850), and he’s a generous member of the community. He supplies free ice for weddings, funerals, and other local celebrations. He has also been known to store wild game—bear and deer—for local hunters in his walk-in coolers.

Finally, Willy came back to the phone. “So . . . soft-shell crab actually shed all summer long,” he continued, “but it’s that first taste of spring, kind of like shad used to be, that causes the frenzy among fishermen and seafood lovers. It’s the signal of the start of beach season nowadays.”

Unlike Endurance Seafood, Full Circle works with a Wanchese trucking company on Roanoke Island to ship most of its catch to a New York wholesaler that serves a number of upscale delis in Manhattan and the Hamptons. Phillips’s standards are extra-high, he said. He insists that all the soft-shells he ships must have two claws and legs on both sides. Others may not hold to this standard, but Phillips is adamant. In addition to the high-end New York markets for live crabs, he also sells to wholesalers and individual restaurants on Maryland’s eastern shore—establishments in Annapolis and St. Michael’s, home of the Chesapeake Maritime Museum. “People know our product, and now they ask for it by name,” he said.

Beyond the tens of thousands of live crabs he ships, Phillips also freezes a portion of his soft-shells and has been able to sell the frozen stock in the off-season to maintain cash flow, especially around Christmas and before the new season for soft-shells begins. He explained:

Hundreds of dozens of frozen soft-shells are flooding the market now from Indonesia. It’s a cheaper product with value added. The Asian crabs are often already breaded and cooked. They only need to be heated. We used to be able to hold our frozen crabs back as a way to cash out in winter, but the market is definitely changing with imports. We are still in a better position with the live market, because of our proximity. You can’t ship live crabs all the way around the world from Asia—at least not yet.

When I asked Phillips how he likes his soft-shell crab prepared, he was definite: “We always remove the mustard.” Mustard (also known as tomalley) is the yellow substance in the middle of the abdomen. He went on:

Some save it and use it for extra flavor in deviled crab and crab cakes, but we don’t. We also take off the “back”—the paper-like shell that is just beginning to form there—because it gives an off flavor and it’s easier to clean the water out that way. When you fry a soft-shell in hot oil, too much water left inside will cause splatter. My mom used to bake them with a slice of butter under each wing, so to speak. You can also marinate and grill them, but it doesn’t take much heat to cook a soft-shell on a grill. A light brown color on the crab is sufficient.

As for size, Phillips said, “The tourists always want to see whales on their platters. But I think the best size is the prime—the four- and- a-half-to five-inch crab. The smaller ones taste sweeter and cook easier. To cook through a larger crab and get the middle done, it means the legs get too done.”

During our exploration of heritage foods across the state, we heard from growers, restaurateurs, and other retailers that the same consumer preference for larger sizes holds true with apples, cantaloupes, scuppernongs, and oysters. But in every case we also learned from the producers that bigger does not necessarily mean better flavor or quality. What it does mean is mostly evident in our waistlines.

Exactly a month after Donna and I first visited Endurance Seafood, we made our way back east. It had been raining more than usual, and Willy Phillips told us by phone that cool temperatures had made the soft-shell harvest spotty. At four o’clock in the afternoon on May 12, temperatures were warmer than any so far this year on the Outer Banks—in the high seventies with gusting winds. As we crossed the William B. Umstead Bridge, Roanoke Sound was violet.

When we arrived at Endurance, Kissy Bridges was shoving a heavy push broom back and forth over soapy concrete floors. The latest shipment of crabs has already gone out for the day. A seeping water hose curled on the floor behind her boots.

We already knew that Kissy was famous for her hard-edged negotiations with the New York seafood wholesalers. “She can cuss like a sailor,” Willy Phillips said, “and she won’t back down if they try to drop the price when the Endurance shipments arrive in the Bronx.”

Donna asked Kissy about the day’s catch. “We only shipped 1,600 dozen today,” she said, and stopped her scrubbing. “I wish it was more like 5,000 dozen—that’s our usual by this time of the season.”

Her father, who had been resting back at the house, came up behind us. “I’m afraid it’s not going to pick up this year, Kissy,” he said.

“Don’t say that, Dad,” she answered, and turned back to shoving the broom.

Bridges invited us to follow him through the warehouse and out back to the shedders. About half of the shedders were populated with crabs that had not yet molted. He pointed out the freshest ones, a dark mass moving underwater. He had pulled them from his pots that morning. He said they usually limit each shedder to about 300 crabs. “Every day we have to move them around to different shedders based on how they’re coming along. These caught today”—he moved toward a full shedder where an occasional claw broke the surface and the water was violently stirring—”they are wild acting. We have to put them off by theirselves. The ones that’s been here for a while have calmed down. But these wild ones will hit or damage the calm ones.”

Bridges moved his hand over the water, and the crabs reached out as if to high-five him. “Yep, these is still wild. They’ll get in a fight and will throw a leg off to get loose. A nub will form and eventually the limb will grow back. We call them false biters,” he said. “That’s why you see some crabs with one claw bigger than the other.”

As he walked and talked, Bridges was picking out empty shells where several crabs had recently molted. He dropped the shells into a basket. He pitched the occasional broken limb and dead crab out into the creek beyond us. A small circular corral made of hardware wire sat in the middle of each shedder. Bridges gently laid the just-molted crabs into these “pens,” where they would be protected from the other crabs. As we made our way down the aisle of tanks, I marveled at how he could discern, despite slightly murky water, the difference between an empty shell, a just-molted crab, and the rest of the circus that was clambering along the shedder bottoms in every direction.

I looked closer. The crabs’ “faces” were eerily animated. They tracked us with their eyes. Their mouths opened and closed in a silent, underwater diction. They brought their big claws forward as if to rub their faces. The tiny parts that flanked their mouths clapped together at times like the pouting lips of a fervent child. One crab would seem to wave a big claw to another across the way. They clowned around, piled on, picked at each other, bunched up, leapfrogged, and raced sideways to new destinations in the shedder. They stared back at us with, what—menace, amusement?

When we came close to another shedder that was full, Bridges moved his hand above the water and the crabs again raised their claws and broke the surface, reaching as if to pinch their captor. “These are all males,” he said. Their legs were a lovely peacock blue. (Willy Phillips later told me that he thinks of the crab color as Richard Petty blue—the precise hue of the race car once driven by North Carolina’s most revered NASCAR celebrity.)

Bridges poked his hand into another shedder, pulled out a crab, and turned it over. It was a female with the telltale red line on the paddler. “She’ll be shedding before dark,” he said. ” We have to separate the males from the females. It takes the males longer to calm down. They’re like lions. They’ll fight you until they get used to being kept.”

Bridges had risen at five that morning and was out on the water by six. Working with “another feller,” as he put it, he checked every one of his 400 crab pots in the sound and creek, returning for lunch before one o’clock. “The crabs out there are looking for a shady place to molt, where they might not be seen by predators,” he told us. “We paint the pots black, and they crawl right in.”

He pointed out several “busters”—crabs with shells that were visibly cracking. Donna rushed over to shoot video of the entire event up close. The steps in this process were apparent, even to the untrained eye. The shell opened at a seam along the hind edge of a buster, and its grayish insides were pushing out. We waited, the hot sun bearing down. After the shell fully cracked, the crab began expelling water, trying to make itself smaller. It took about ten minutes for the crab to work its way free. With a final thrust, it pulled its limbs out of the old claws, much like an elegant woman might remove an elbow-length evening glove.

“Sometimes,” said Bridges, “if a feller gets stuck, another crab will come over and help pull him out. See there?” We watched a buddy crab holding a buster, grounding him, almost like a spotter for a gymnast about to perform a dangerous maneuver. “Soon as he’s out, he’ll start rocking side to side to fill himself back up with water,” Bridges said. Another buster nearby seemed stuck, his seam only halfway open at one end. “He might not make it,” Bridges added.

When the crab that Donna had been recording with her camera finally broke free, I looked away for an instant and then back into the tank. I was confused. Which was the live crab that had come out, and which was the shell? The translucent one didn’t move. Somehow, though, my mind believed that the ghostly figure was the new crab—the pale soul disengaged from its earthly shell, its see-through self holding still, exhausted. But it was the darker twin that suddenly moved. It looked more like the others that had not yet shed.

How Murray Bridges can spot the soft-shells at the precise moment of their transformation and then transfer them to the safety of the corral is a marvel, as is the sight of a molting crab.

This essay first appeared in Food IV: The Coast (vol. 24, no. 1: Spring 2018).

Georgann Eubanks is a writer and documentary filmmaker from Carrboro, North Carolina. She is the current president of the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association and is a past Chair of the North Carolina Humanities Council. She is the author of the Literary Trails of North Carolina series from UNC Press.

Adapted from The Month of Their Ripening: North Carolina Heritage Foods Through the Year. Copyright © 2018 by Georgann Eubanks. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.org.

Illustrations: Natalie Nelson

- Murray Bridges and Brady Bridges, in discussions with the author, April 15, 2016, and May 12, 2016. All references to the Bridges’s work at Endurance Seafood are drawn from these two interviews.

- A photograph of Murray Bridges by Donna Campbell appears on this essay’s title page.

- Harriet M. Perry and Ronald F. Malone, Proceedings of the National Symposium on the Soft Shelled Blue Crab Fishery (Baton Rouge: Louisiana Sea Grant College Program, 1985), 91; Biennial Report of the North Carolina Department of Conservation & Development, no. 7 (1937), 28.

- Ian Doré, The New Fresh Seafood Buyer’s Guide: A Manual for Distributors, Restaurants and Retailers (New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 1991), 38–39.

- Arnold H. Lubasch, “Mafia Runs Fulton Fish Market, U.S. Says in Suit to Take Control,” New York Times, October 16, 1987, http://www.nytimes.com/1987/10/16/nyregion/mafia-runs-fulton-fish-market-us-says-in-suit-to-take-control.html.

- Feather Phillips, email communications, April– May 2016. All references to Feather Phillips’s work at Full Circle Crab are drawn from these correspondences.

- Willy Phillips, discussions with the author, April 15, 2016, and July 6, 2016. All references to Willy Phillips’s work at Full Circle Crab are drawn from these conversations.