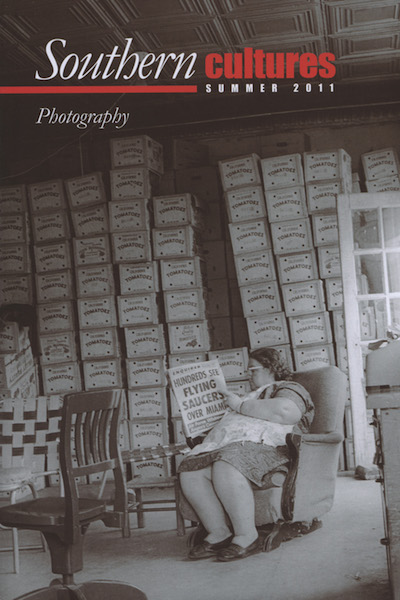

“Photography in its finest and most decisive moments is about those tired or ignored or unseen parts of our lives, the mundane and worn paths that sit before us so firmly that we cease to notice. It is, we might say, about rebuilding our sight in the face of blindness, of recovering our collective vision.”

I am at war with the obvious,” wrote William Eggleston as he reflected on his own photography in a brief afterword to his book The Democratic Forest. Like other seemingly simple, terse dictums, one could initially find Eggleston’s words clever but all too evasive. I increasingly come back to his words, however—or, rather, the words come back to me—and see them as a concise and profound summation of the stance of the visionary photographer, as a definition of the role of the truest of artists. Photography in its finest and most decisive moments is about those tired or ignored or unseen parts of our lives, the mundane and worn paths that sit before us so firmly that we cease to notice. It is, we might say, about rebuilding our sight in the face of blindness, of recovering our collective vision. And yet, the photographer is also in a perpetual battle to see beyond and around what he or she has already seen, to bring to their own work a “sovereign vision,” to borrow Walker Percy’s words, that is not obvious or redundant or derivative. This is particularly true in the American South where many forms of art—fiction, Hollywood movies, painting, popular music, to mention just some—have so defined and fixed our image of the region. The photographer must do battle with the mundane, as Eggleston so aptly characterizes it. And as war never ends, neither does the task to confront the “obvious” and make it new, make it sing, move it from ordinary and invisible to astonishingly beautiful and fully seen.