This is a review of “The Dirty South” at the VMFA where it originated and hung until September 6, 2021. The show is now on view at the Contemporary Art Museum, Houston, through February 6, 2022, and images in this feature are courtesy of that museum. Later, it will travel to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, March 12–July 25, 2022; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver, September 2022–February 2023. Please note that the installations will vary in each location.

“What you really know about the Dirty South?” I thought of that line, the refrain of Atlanta hip hop group Goodie Mob’s 1996 song “Dirty South,” often during the months from the November 2020 election through the January 2021 Georgia runoffs. And the answer, at least among a circuit of people who work in academia and art museums, a world in which I spend a lot of time, is not a heck of a lot. When I started telling those friends and colleagues several years ago that Georgia would be the next blue state, they reacted with the kind of bemused condescension younger people employ when trying to help older people with new technology. Yet, as I did research that required frequent travel to the state’s sprawling suburbs and booming college towns, the transformation was obvious. To see that massive change had already come, I suggested, people from elsewhere simply needed to do more in my hometown of Atlanta than change planes. White flight suburbs still exist in a metropolitan area which sprawls for miles, but they are so far out now you feel like you are in South Carolina. Everywhere else you go, Black and Brown people are there. In Atlanta and other job-rich southern cities like Houston and Charlotte, a new urban and suburban Black southern culture has been flourishing for more than a quarter of a century.

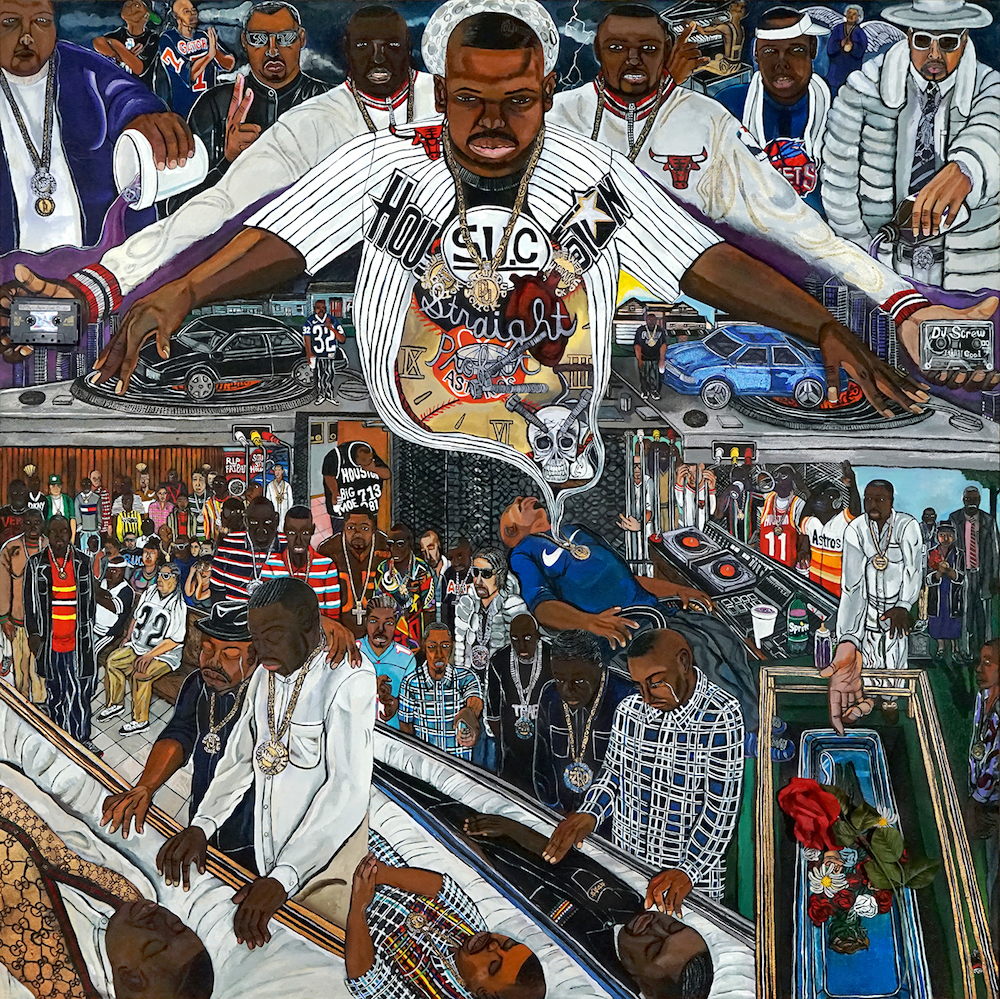

While none of this is news to Black southerners, this world has mostly been ignored by the institutions of high art. The wondrous achievement of the VMFA’s “Dirty South” exhibition, curated by Valerie Cassel Oliver, is to showcase the visual art that has inspired, grown out of, and commented on this southern Black life. Rich and rambling, bursting with over 140 pieces by more than 100 Black artists making work in and about the South over almost a century, this show feels no need to hew too strictly to any single story. Is it about music and the Black South? Or the particular history of hip hop and contemporary visual art? Or what modern and contemporary Black artists have to say to a present in which too many Americans are trying to survive on gig jobs with poverty wages amidst broken infrastructure? Why should it settle for one? “The Dirty South” takes up all these themes. At its most ambitious, the exhibition simply argues that the art forms and lived experience of the Black South and its diaspora are the essential source of contemporary American life. “The South is the bedrock. It is the point of origin,” Oliver has said. “[The exhibition] is my love song, if you will, to the South, being a Southerner myself.”

“The Dirty South” begins in the VMFA lobby, where a Cadillac transformed into a type of car called a “slab” (for “slow, loud and banging”), by New Orleans artist Richard FIEND Jones, a.k.a. International Jones, grabs your attention. There is nothing really the museum could do about it, but this piece needs to move for us to hear and see and feel its power, the way its sound system and its form remake the world as it rolls along.

The main exhibition opens with a sequence that is simply stunning. In Paul Stephen Benjamin’s installation “Summer Breeze” (2018), video loops of a Black girl on a swing sequenced so that she is flying backwards and forwards simultaneously play on televisions stacked in a pyramid. Just in front, the central, largest TV in a row of five repeats a 1939 clip of Billie Holliday performing the song “Strange Fruit.” The four smaller screens—two on each side—loop a clip of Jill Scott performing the same song in 2015. History, the piece announces, moves in multiple directions. It doesn’t just arc or spiral. With small variations, it repeats. What would it take to break out, to send this Black girl soaring over all that history, the violence and the violations of Constitutional and human rights, borne up by the beauty of Black women’s voices? The clips and the lyrics subtly change over the course of the twenty-minute piece, though most viewers did not stay that long during my visit. No matter—the sound of the piece follows you into the show. I read the opening wall text and viewed the first few rooms haunted by Holliday’s voice singing “Black bodies swaying in the summer breeze.”

Benjamin’s piece makes the subtle effects of Beverly Buchanan’s beautiful sculpture “Untitled” (1978), from her Frustula series, impossible to ignore. Against the recent history of statue removal, Buchanan’s piece functions as a kind of anti-Confederate monument. Its minimal lines, weight, and ground-hugging forms work as the opposite of the ornate, soaring fantasies of white men and horses on pedestals that have recently come down in Richmond and Charlottesville. With its aesthetics of ruin, Buchanan’s work speaks to the lives of too-little-known Black men and women whose labor has built the South.

The final piece of this opening trio is Allison Janae Hamilton’s video installation, “Wacissa” (2019), named for the river and town near where she grew up in Florida. To a soundtrack of rushing water, moving images render what it looks like under and on the surface of this small river, speeding up and then slowing down as they bleed across two huge screens. The effect is otherworldly, a gorgeous view of another realm. But for those who read the wall text, history adds another layer of significance. Plantation owners forced enslaved laborers to dig a canal to extend the Wacissa past its natural endpoint in a swamp in order to connect it to the Aucilla River. They hoped to create a navigable waterway to ship their cotton to the Gulf, but the Florida Slave Canal was never deep enough for large boats. Hamilton’s piece is thus also a memorial, an elegy for unknown men and women who dug through the heat and the mosquitos and the mud to build this folly.

As two of these first three works make clear, the sculptors rule this show. Farther into the exhibition, in a gem of a small room, Theaster Gates’s homage to Black labor, “Shoe Shine 1” (2009), sits radiant like a cross between a color block painting and a throne. Another brilliant trio sits opposite this piece on a raised platform like a stage. David Hammons’s “Strange Fruit” (1989) turns rubber, wood, concrete, and found objects into a beautifully lyrical, treelike form that works in tension with what the title, a metaphor for lynching victims, reveals as its subject matter. From just the right angle, the Hammons piece hangs over and above Melvin Edwards’s “Hers” (1963), a welded steel fragment that evokes nuts and bolts, a few links of chain, and what looks like a wire made to hang from the ceiling and hold a light bulb, a piece from his Lynching Fragments series. This smart installation makes the works look like they were made for this pairing. At the end of the row, Mel Chin’s “Night Rap” (1993), a construction made of a blackjack, a microphone, and a mic stand, stands in threatening counterpoint, like a sheriff or a police officer, armed and ready. In other rooms, William Edmondson’s limestone “Angel” (1932–1938) stands watch like a guardian, an earlier, representational version of Buchanan’s anti-Confederate monument. Renee Stout’s “She Kept Her Conjuring Table Very Neat” (1990) evokes African survivals and the wisdom, artistry, and authority of Black women. The title of Thornton Dial’s construction “Foundation of the World (A Dream of My Mother)” (1994) transforms what looks like a throne with a halo into an evocation of a Black woman so powerful that her lap has become the seat of the universe. Nick Cave’s “Untitled (Soundsuit)” (2010) dazzles like all pieces in this series, conjuring song and dance and pageantry and pleasure. Sculpture seems too narrow a term for the brilliance of these artists making three-dimensional work.

The painters, or more accurately, artists working in two dimensions, are also dazzling. Deborah Roberts’s “Let Them Be Children” (2018) is marvel of composition and contradiction, its collaged child subjects simultaneously playing and warding off trouble. The sculptural bodies of the worshippers in Benny Andrews’s “Rural Meeting” (1994) convey the ecstasy and otherworldliness, the dance and the song, of a Black church filled with the Spirit. The red and blue lines in Rita Mae Pettway’s “Housetop (Fractured Medallion)” (1977) create the illusion of squares stacked in space, a powerful graphic effect that lifts the quilt off the wall. Beaufort Delaney’s “The Burning Bush” (1941)—its title a reference to the Bible story in which the fire that does not consume is the sign that God is present—is a bright riot of thick color. Romare Bearden’s collage “Three Folk Musicians” (1967) uses contrasting colors and patterns to put its flat shapes in motion and suggest song is pouring out of its paper instruments. In “Untitled Slab (cotton island)” (2018), Kevin Beasley presses old clothes and other found objects together with resin to create a flattened image that dances between the abstraction of its overall form and the particularity of its material.

I went to the Dirty South exhibition to report on the photography, but many of the pictures on display seem to function more as illustrations than as equal works of art. The major exception is the work of Houston-based photographer Earlie Hudnall, whom I learned of here for the first time. In an achingly gorgeous silver print titled “Blackwater Baptist Church, Mississippi” (1990), a wrecked church is obscured by the pine trees growing up its façade. A man in a cap and suspenders, small in the image, enters the open doorway, perhaps to fetch some tool or animal feed because the building has been turned into a shed. The church’s dark, unpainted bulk fills over half the vertical frame, leaving the branches of the pines soaring above its roof to stand out against sky. This sanctuary may have been abandoned by its congregation, but the glowing light against the cupola suggests God is still there. Calling up earlier images of Black churches by artists like Walker Evans, William Christenberry, and others, Hudnall’s picture manages to comment on both the centrality of rural churches in Black life lived on the land and also the long history of white photographers’ interest in this subject. Another standout is Jonathan Mannion’s “Photographic Print of Killer Mike and Family” (2004), an image that transcends its role as a document. Standing in front of a tiny house, the rapper writes something in a notebook—an autograph or a lyric or a phone number?—while family members crowd around him. Mannion creates a nighttime scene here that somehow hovers at the edge of myth.

The show ends with Arthur Jafa’s 2017 video “Love is The Message, The Message is Death,” a collage of his own images and every kind of found footage imaginable set to Kanye West’s song “Ultralight Beam.” This Jafa work, like his longer video piece “The White Album,” which won the Golden Lion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, probes the overlapping categories of Black culture, pop culture, history, and fantasy and the role of sounds and images in creating and confusing and transcending binaries like life and death, love and hate, pleasure and violence, beauty and ugliness, and even black and white. In these works, Jafa seems to have quilted sound and image together into an entirely new form. More than any other artist working in the US, he makes it clear why we need art to survive this present and imagine a different future.

The Black South and its diaspora have been the essential incubator of contemporary American culture since the invention of the blues. In turning this idea into a show, VMFA welcomes a broader audience and transforms itself into an art institution that takes seriously the history of the place where it stands. This new direction is also evident in the acquisition of Kehinde Wiley’s sculpture “Rumors of War” (2019) and previous, smaller shows like 2020’s “Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop” about the Virginia photographer and other members of the New York City–based collective of Black photographers.

As the hip hop world long ago discovered, the Black South has something to say. For those who have already been listening, as well as those doing the talking, this exhibition functions as a space of pleasure, reflection, and inspiration, a testament to the aesthetic richness of this collision of race and region. For everyone else, the show offers a much-needed education. The Dirty South is America.

This essay is part of our Shutter art and photography series.

Grace Elizabeth Hale is Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and a 2018–2019 Carnegie Fellow. She is the author, most recently, of Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture (2020). She has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post, Slate, American Scholar, and Southern Cultures. Her new book, forthcoming in 2022 from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, is The Lyncher in the Family, is a history of her grandfather, a Mississippi sheriff, and white Americans’ inability to reckon with the history of white supremacy.

Header image: Jason Moran, STAGED: Slugs’ Saloon, 2018. Mixed media (wood, paint, juke box player, cello, drum set, saw dust, construction hardware, wallpaper, Plexi glass mirror, tin, fabric, vintage outlet cover), and sound. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Commissioned by Walker Art Center, T.B. Walker Acquisition Fund 2018, 2018.14. Installation view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2021. Photo by Sean Fleming.