As we start to celebrate our 25th year of publication, we look back at the first essay in our inaugural issue.

Welcome to the first issue of Southern Cultures, a new quarterly of the American South. As always, the South attracts a considerable share of attention today, from defenders and detractors, reformers and traditionalists, historians, novelists, literary critics, social scientists, journalists, and politicians. As all these folks keep busy, each group telling about the South in its own way, too much of their conversation takes place in isolation, in narrow professional journals, in homogeneous knots of talkers, in separate cabins on a far-flung landscape, if you will, or in isolated corners of the big house. Up till now, there didn’t seem to be many places to bring these folks together .

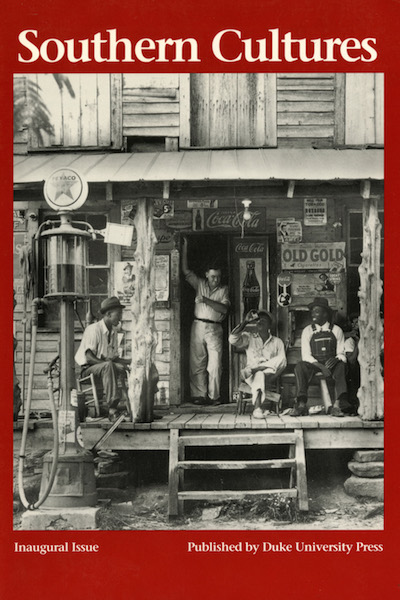

There used to be a time when southern houses were known for their front porches: a place to cool off, to watch the world, to talk things over. The home and the road came together at the porch, and people who didn’t meet anywhere else could meet there for conversation and business. Today, in a world of air conditioning and mass-market subdivisions, the front porch is not as prominent in southern life as it used to be. As editors, though, we hope this new journal can borrow some of its ambience and revive some of its purpose. Southern Cultures is, in effect, the front porch of our new Center for the Study of the American South. It’s our face to the world and it’s a place to mingle. We’re especially proud that it is a joint construction project of the University of North Carolina and Duke University Press—you might say it’s a renovation project rather than new construction, since it gives us a chance to revive a flagging conversation about southern matters that both Chapel Hill and Durham once were famous for. (Editor’s note: UNC Press became our publisher in 1996.)

The home and the road came together at the porch, and people who didn’t meet anywhere else could meet there for conversation and business.

Some porches, of course, were built to overawe visitors, not to entertain them. (Later in this issue, Catherine Bishir tells us a lot about those.) And there were rules about who could and could not use the door. Our porch is not like that. On the contrary, we want this journal to bring talkers together who may have been talking too separately. We want it to appeal to thoughtful readers from outside the academy and to scholars who want to stretch beyond their own specialties. As our readers and writers, we want historians keen to learn about literature, literary critics ready for insights from anthropology, political types eager to get down with southern music, readers of all kinds inspired to think seriously—if not too solemnly—about high cultures, pop cultures, and folk cultures in the South.

In 1935, W. T. Couch put together an ambitious collection of essays called Culture in the South that challenged the nostalgic, monochrome southern portrait that the Nashville Agrarians had presented in I’ll Take My Stand. “Life in the South,” Couch wrote, “is not a simple affair. It is varied from class to class, and is further complicated by wide differences in political, economic, racial, educational, and religious faiths.”

We agree, and that’s why we went one step further than Couch and gave our journal a plural title. To invert an observation by W. J. Cash, although it may be said that there is one South, there are also many Souths, and many cultural traditions among them. Beyond the widely recognized divisions of race, class, subregion, and gender, there are rifts between the campus and the community, among the various professional specialties, and among the many schools of political and moral thought. The factions are often in dispute with one another, and culture has been the theater of conflict as much as the occasion for sharing. We want Southern Cultures to reflect this diversity. Contributions to this introductory issue deal with literature, architecture, linguistics, and oral history. Our authors are black and white, male and female, native southerners and newcomers.

That’s why we went one step further . . . and gave our journal a plural title.

But even as we embrace diversity, we also see a basis for a common conversation. There is one South spawned by its many cultures. Without forcing an unnatural consensus on anyone, we want this journal to reflect on what southern cultures share, as well as on what divides them, to bring together people who may have been talking past each other, to create a front porch atmosphere that leads to uncommon conversation.

There is one South spawned by its many cultures.

We were fortunate to find several such pieces for this issue. For example, Catherine Bishir‘s lead-off article does just the kind of thing we had in mind when we thought up the idea of Southern Cultures: it makes us think twice about southern landmarks that we ordinarily tend to take for granted. Michael Mont gomery discusses the future of the southern accent, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese examines the South’s confrontation with modernity, and Sherman James provides a narrative from a southern tobacco sharecropper. We hope you’ll also find some of our special features thought-provoking—that’s why, for example, we’re leaving it to you to draw your own conclusions from the polling data presented in our “South Polls” section.

We want your company. Drop by and sit a spell. Listen in, and tell us what you have to say.

—Harry L. Watson and John Shelton Reed, Editors

Header image: Negro family on front porch of old home on badly eroded land near Wadesboro, North Carolina, by Marion Post Wolcott, December 1938, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Subscribe now to receive all four special 25th anniversary issues + a 25th anniversary tote. Learn more about our history here.