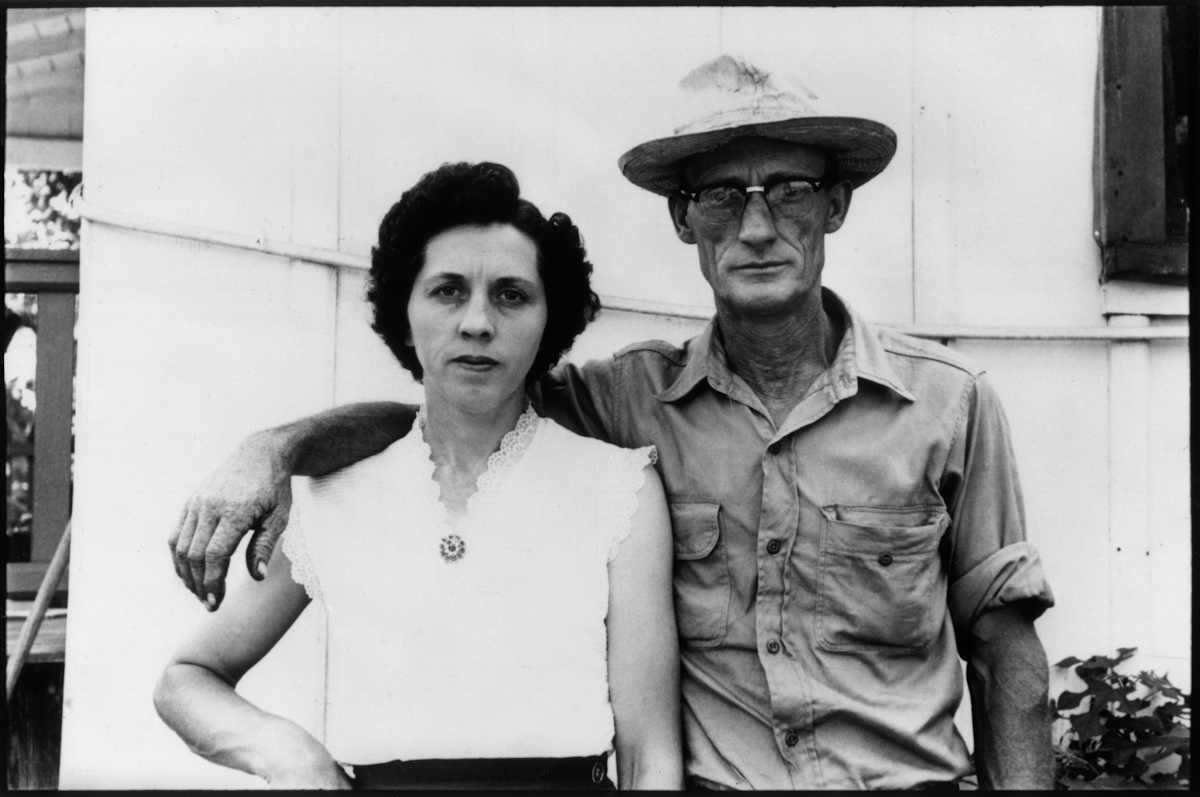

On a sticky June Sunday in 1959, two people meet each other outside an eastern Kentucky hamlet called Daisy. A twenty-seven-year-old college grad living in New York City, the grandson of Russian Jewish immigrants, wants to experience the Great Depression, and he is listening for music that might work like time travel. The other man, a forty-seven-year-old out-of-work miner and a musician, is looking for a job.

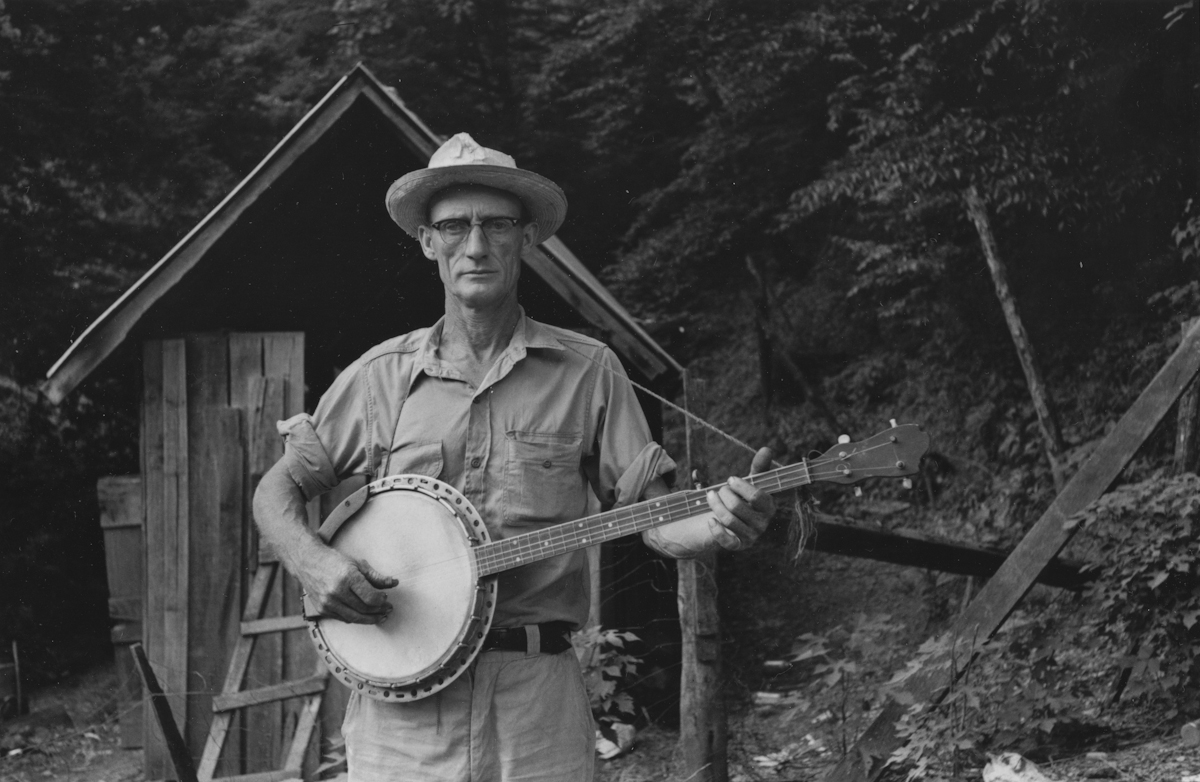

John Cohen describes Roscoe Halcomb as “a little wiry person, stooped from hard physical work, coughing from asthma, black lung, and too much smoking.” But then Halcomb picks up a guitar, tunes it like a banjo, and sends his nasal, keening voice high as he picks and strums the rhythm on the strings. The song is one Halcomb claims as his own, “Across the Rocky Mountain.” Cohen is mesmerized, made raw. He does not know it yet, but he will talk about this meeting for the rest of his long life. If Roscoe Halcomb wrote his thoughts about Cohen down, they have not survived.

Cohen and Halcomb never do really understand each other, not then or at other meetings over the next two decades. Cohen even records his name wrong, calling him Holcomb. But their encounter creates a kind of collaboration that produces profoundly meaningful art: a masterpiece of a film, a selection of beautifully intimate photographs, and an exquisite collection of recordings.

Half a century later, decades after Halcomb dies and around the time Cohen retires from his work as a photography professor, I meet the artist in the back of a theater in Charlottesville after a screening of some of his films. At a coffee shop the next day, he tells me about finding Roscoe and other musicians in Appalachia. As he talks, he sits on the edge of his seat. I can imagine just how engaging he must have been on those trips, young and handsome and sparkling. Even in his mid-seventies, he radiates interest. Leaning forward in his chair, he smiles with his eyes and his shoulders as well as his mouth as he stares intensely. I want to say he flirts with me, but that is not entirely accurate. He asks me to join him as he flirts with life. He makes it clear the world is out there. He might be too old, but I am not. In every way he can possibly communicate, he urges me to travel, to make that leap, to go.

Cohen and I never really understand each other either, despite the fact that we are both white college professors with a shared interest in the history and cultures of the rural South. Our different genders and ages are part of it—he’s a man born during the early years of the Great Depression, and I’m a woman young enough to have small children. While it may be related to these circumstances, our most meaningful difference seems more elusive and abstract, and additional conversations over the next decade-and-a-half only deepen this feeling. It’s somehow about sensibility, though we are both pretty open to the world. It’s also about theory, our different understandings of how people know things and what they can know and how much their own position shapes their understandings. If I had to nail it down, I might say it’s about faith. John Cohen believes wholeheartedly in the possibility of hitting the road and transcending your own time and place. I like to go, but I suspect we’re not that buoyant. I think we drag our homes around with us. I doubt.

John Cohen believes wholeheartedly in the possibility of hitting the road and transcending your own time and place. I like to go, but I suspect we’re not that buoyant. I think we drag our homes around with us. I doubt.

John Cohen’s life as an artist grew out of his travels. Trying to describe his half-century of work for a 2001 book, he explained, “I set out to get a vision of the wider world . . . Along the way, I confronted myself.” Cohen wanted to not just listen and look at art and music from elsewhere but “to experience and inhabit these things personally.” His achievements were staggering. As a co-founder and member of the old-time band the New Lost City Ramblers, he helped create what became the postwar folk music revival. Along with others like his brother-in-law Pete Seeger and his other brother-in-law and bandmate Mike Seeger, Cohen inspired a growing interest in what was then thought of as “folk” music, genres and styles out of favor with the mid-twentieth-century music business. As important as the particular types of music that revivalists helped save was their broader message about the value of cultural artifacts produced in the past. By teaching some young people to reject a relentless focus on the future, revivalists transformed American culture. But Cohen did not just perform. He also created an invaluable archive by recording the musicians he met in places like eastern Kentucky and southwestern Virginia and the Peruvian Andes.

These achievements would have been enough for most mortals, but Cohen, who had earned an MFA at Yale, also became the folk music revival’s finest artist. He made work as a photographer and filmmaker. He crossed mediums and invented new hybrid genres in ways that probably hurt his career then but are standard now. Part of a circle of younger, New York–based photographers, he helped bring a midcentury bohemian interest in subjectivity to a documentary aesthetic then dominated by Depression-era ideas about objectivity. He wanted his photographs and films “to integrate feeling with seeing,” to reveal not only what his subjects looked like but also some trace of their interior lives.

Across his long career, Cohen made his art by recording and photographing and filming people he understood as alienated from modern America. “My involvement was always with outsiders,” Cohen wrote, “artists, poets, mountain musicians, fiddlers, Peruvian Indians. . . .” But such radical leaps across chasms of difference are suspect now, and remain an ongoing conversation in documentary projects. Today’s culture wars do not allow for categories of identity capacious enough to include Cohen and Halcomb. Representing “the other” may be a form of love, but it is also always a kind of theft. No matter how thoughtful the traveler, some kind of questionable borrowing—a smudge of blackface minstrelsy, a whisper of imperialism—clings to the act. Misrecognition is inevitable. We know that, historically, the costs to the people represented, in terms of both treasure and identity, have been great. And we are rightly cowed by the risk. In these exchanges, all the things humans like to keep hidden—privilege and vulnerability, need and desire—have a tendency to erupt on the surface like an angry rash.

In our conversations, Cohen never seems to grasp this critique of his work. He understood that some people felt he did not have the right to represent Appalachian or Andean culture as he had done in many of his best-known recordings, photographs, and films. And he had a counter. If he had not made these leaps, some of the music and the beauty of these particular times and places would have been lost to human history. There was no way to test the truth of this counterfactual, and our talks spun around in lively circles. My point ran deeper than an argument about identity politics, and his rebuttal reached far beyond his not inconsiderable ambition for his work. I worried about the cost of representing or trying to speak for others. He worried about the cost of not representing them at all. We never did agree.

Now Cohen too has died, and I am still wondering. Scholars and artists have debated the more general version of the problem for decades. The journalist Amanda Petrusich put it this way in a piece she wrote about Cohen: “When does folklore, enacted on impoverished rural communities, begin to mimic a kind of inverted cultural imperialism?” But my question is both more specific and more simple: Is it okay to love the work Cohen made about the man he called Roscoe Holcomb?

I worried about the cost of representing or trying to speak for others. He worried about the cost of not representing them at all. We never did agree.

John Cohen grew up believing in the power of sound. His ancestors had fled pogroms in Russia. As a child, Cohen accompanied his Orthodox grandfather to the synagogue on High Holy Days and listened as men kissed the Torah and sang “weird and deep” tunes with unfamiliar melodies and rhythms. The closest thing he heard to these sounds at home were the Black spirituals his father loved and studied and sometimes sang. Cohen’s secular parents learned Eastern European folk dances at a Lower East Side settlement house before he was born, and in Queens when he was a child, they danced and sang with their friends for fun. Cohen’s mother often dressed up in Russian peasant clothes for these occasions. Even after his parents moved the family to Long Island, his mom sang European folk songs around the house. Music could take you to other times and places.

As a sixteen-year-old in the late 1940s, Cohen fell in love with Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads, an album of songs about rural people struggling during the Great Depression that came out when he was eight. Yet it was not enough to listen. He learned guitar so he could play the music and understand how it was put together. The invention of rock ’n’ roll was still a few years away, and no one at his suburban high school played guitar then. His new skill did not make him popular. He did not fit in at Williams College either. Instead, he hung out in the library and listened to Library of Congress recordings of white and Black southerners, and he taught himself to play the banjo. In 1951, he transferred to the art school at Yale. With others like his future bandmate Tom Paley, he created a folk music community around a regular series of hootenannies where people played and sang together. Cohen spent part of a college summer hitchhiking through Virginia and North Carolina, looking for traces of the music he loved and mostly failing. In 1954, closer to home, he was more successful. He met blues musician Reverend Gary Davis and returned to visit him in Harlem often, lugging his camera as well as a giant machine that was the first tape recorder he every owned on the bus all the way from his parents’ Long Island home.

After finishing his undergraduate degree, Cohen returned to Yale to study for an MFA. His teacher, the artist Josef Albers, told his students, “I believe in search, not research.” Inspired, Cohen cobbled together some thesis funds and used the money to travel to Peru. He had seen Andean weavings, most likely in textile artist Anni Albers’s studio, and he wanted to experience life there firsthand and to watch and listen as locals made textiles and music. Back in the US, he joined another of his Yale teachers, the artist Herbert Matter, then at work making short documentaries about dancing in Black churches in Harlem, an area of the city Cohen knew a little about because of his visits with Davis. After Cohen graduated, he moved to New York to make art. To pay the rent, he worked as a freelance photographer. He also performed and put out records with the New Lost City Ramblers.

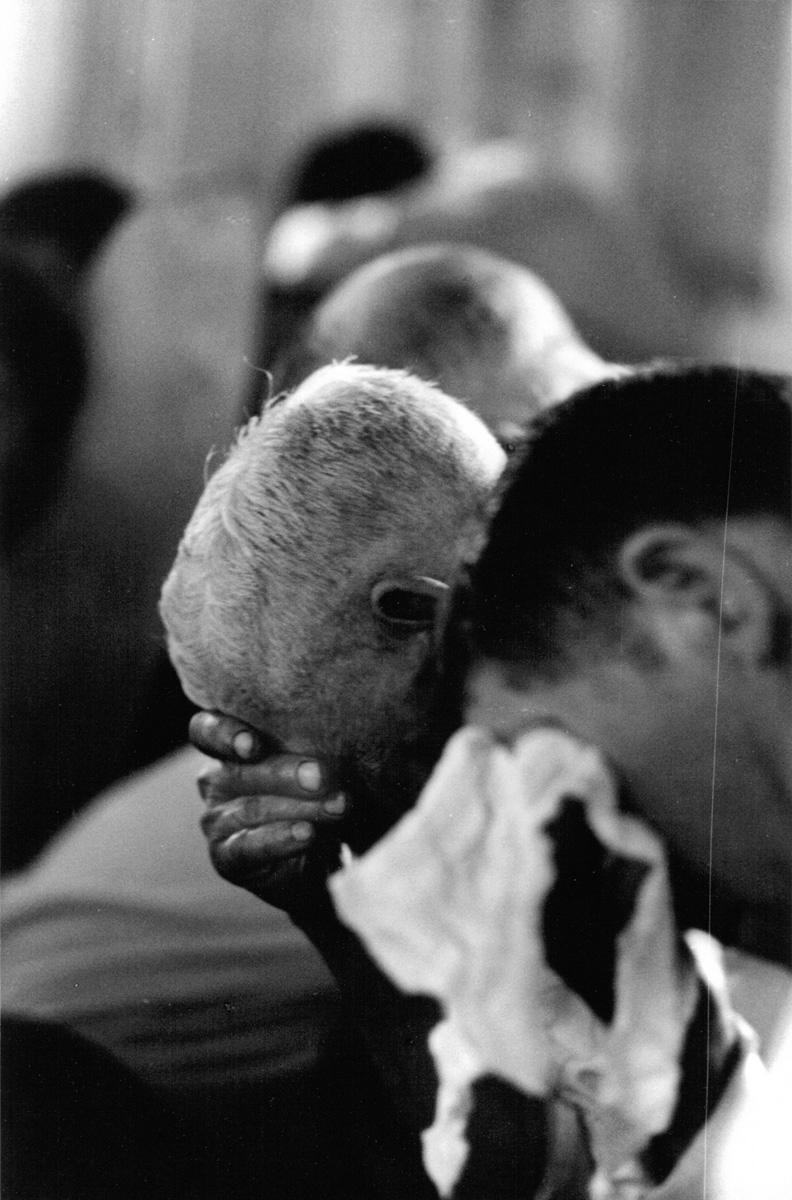

In the city, Cohen’s interests as an artist developed in tandem with his work as a musician and collector. Music was “a many-sided involvement”: “I photographed it, performed it, presented it, recorded it, and made films about it.” Now he could take the subway to Harlem, that place full of the kind of music he loved. On Sundays, he walked the streets there with his camera, listening for singing. When he heard something interesting, he followed the sound up the stairs of narrow buildings to small rooms where African American congregants worshiped in informal churches. “In every sense, they filled my needs with a great mix of spirit, music, dance, trance, and raw energy,” Cohen remembered. His subjects would have called this experience the presence of the Holy Spirit.

Living in an illegal East Village loft, Cohen became friends with his neighbor, the photographer Robert Frank. Frank was at work sifting through thousands of photographs he had made on his mid-century drives across the country for the book that became The Americans. Frank had also started experimenting with films. Through Frank, Cohen met the writers Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Gregory Corso, and he took photographs on the set of Frank’s Beat film Pull My Daisy. In 1959, Life paid him for a “first look” at his photographs of this crowd, and Cohen used the funds to travel: “I saw the opportunity of visiting eastern Kentucky as another foray into a new world for me.”

Traveling in the southeastern United States then could be difficult and at times dangerous. Few good roads cut into the mountains. Cohen packed up some clothes, his Nikon Rangefinder, and a Magnamite tape recorder (which ran off a hand crank rather than a plug) and bought a bus ticket to Hazard, Kentucky. After a few days there, he bought an old car in order to drive back into the hollows. At gas stations, where he went for help when the car broke down, workers asked him what he was doing. It was not an innocent question. In the minds of some locals, a Jewish guy with a New York accent and a camera must be trouble, an “un-American” agitator working for a union or for civil rights. Robert Frank got run out of southern towns and even ended up in jail once. Cohen survived on his honest answer—that he was looking for banjo players—and more than a little luck. And he returned again and again, recording musicians and taking photographs in Kentucky and Virginia and North Carolina over the next decade. Making this art was not easy. Cohen had courage.

Cohen came of age at a time when representing “the other” still looked like progressive politics. Today, an artist with Cohen’s sensibilities might investigate people or places connected to her own past. Sometimes this strategy produces great art. Sometimes it fails. No contemporary photographer has made more exploitative photographs of southern mountain people than Shelby Lee Adams, an artist with Appalachian roots. But even when the art flounders, the politics work. The artist escapes the accusatory question: What makes you think you can represent these people?

Even if Cohen had wanted to go this route, where would he have traveled? Growing up, he did not hear much from his older relatives about the family’s past. After his first Kentucky journey, he visited his grandmother and pressed her to share a childhood memory. She complied: “I stepped out of the house. The sun was shining and a horse and carriage ran by. The people had their heads cut off. There was a pogrom, so I screamed and ran back into the house.” My own grandmother, who experienced profound poverty in rural Mississippi when she was a child, shared a similar attitude. For some people, history is too painful to remember, much less to share. They prefer to live in the present.

In contrast, Cohen wanted to, as he called it, “visit the past.” By the time he reached adulthood, the Russian Jewish world of his grandparents was gone, ravaged by violent anti-Semitism, exile, and revolution. Across the continent, little of what Cohen’s parents thought of as Jewish folk culture survived the Holocaust. Singing and dancing in New York social halls helped his parents stay connected to what they imagined as the old world. But this kind of reenactment was never going to be enough for Cohen, shaped by the existentialism of his teachers and friends and trying to find his way as an artist. He wanted to be consumed. He longed for the kind of immersion that could produce transcendence.

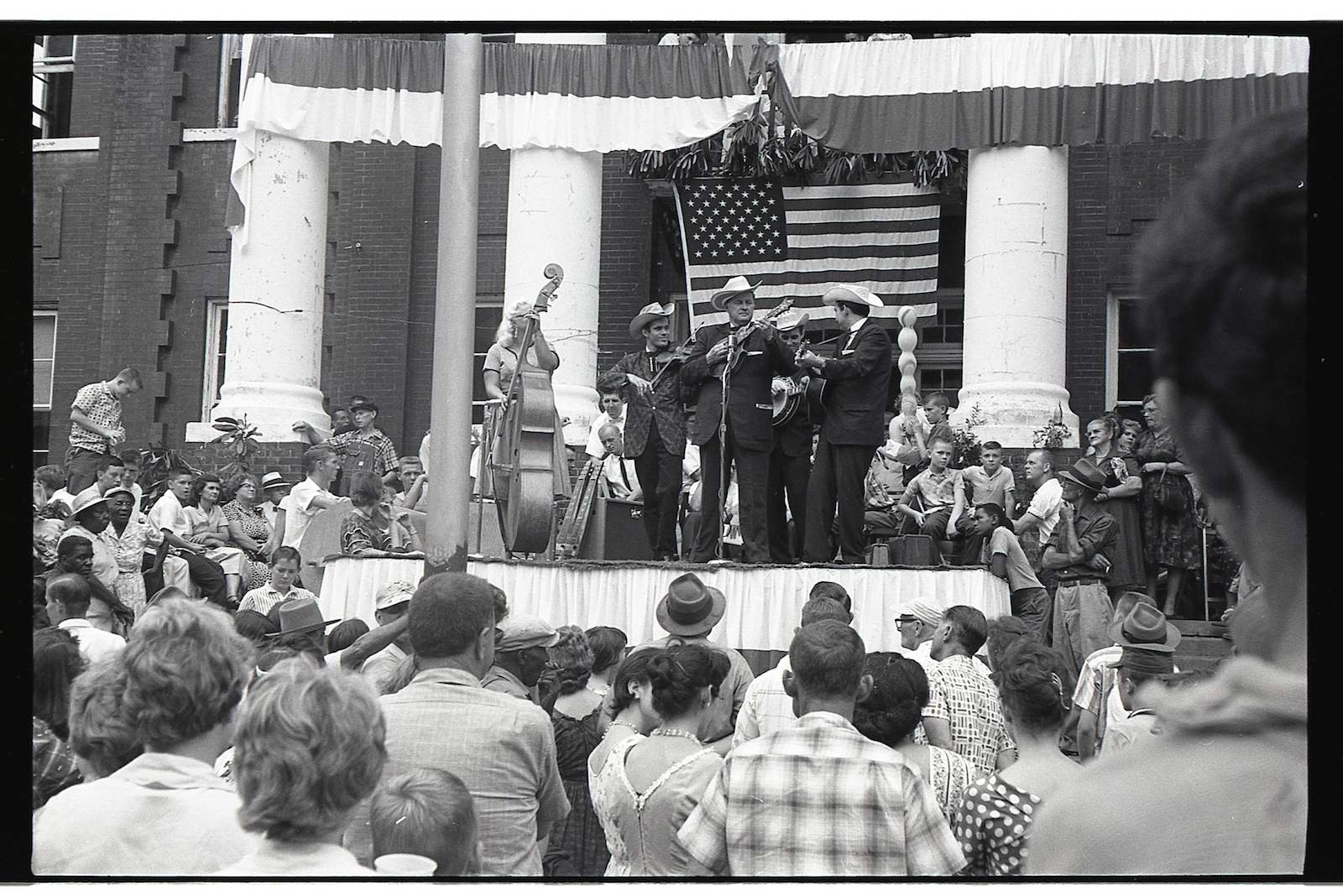

Cohen finally found what he had been searching for when he met the man he called Roscoe Holcomb. Over the next two decades, he spent more time with the older man in Daisy, Kentucky, as well as on the road performing at concerts and folk festivals and recording in places like New York and Chicago and Berkeley and across Europe. Still, the standard forms of folk revivalism—field recordings, musician portraits, and live concerts—were never quite enough. Cohen the artist also tried to create something more immediate—photographs and films with such presence and intimacy that they invite you to walk around in their worlds. And Cohen’s reworking of these materials did not stop when the older man died in 1981. For the rest of his life, Cohen kept returning to his “Holcomb” materials. His 2012 book The High and Lonesome Sound: The Legacy of Roscoe Holcomb collects most of this work, photographs Cohen made in Kentucky, Virginia, and North Carolina on that first 1959 trip and subsequent visits, a DVD of Cohen’s two films about Halcomb, and a CD of Halcomb’s music.

No matter how many times I listen to and look at this work, I keep returning, too. On one level, I am an interested scholar. I want to hear the music and see the photographs and films and think deeply about the history of these two men’s encounters. But this art also speaks to me at a level that’s not about analysis. Its arresting beauty gets into my skin and the muscles of my limbs as well as my brain. Somehow, despite my doubt, I am transported.

Cohen the artist also tried to create something more immediate—photographs and films with such presence and intimacy that they invite you to walk around in their worlds.

The music came first. Cohen could put on his revivalist hat and talk like a scholar about Halcomb’s influences, the unique way the older musician fused the sacred and secular musical styles he learned growing up with what he heard on the radio and at dances and bars—hymns from the Old Baptist Songbook, the faithful singing and playing guitar in Holiness churches, and mountain neighbors playing old-time music, bluegrass, and the blues. He could also put his artist hat on and invent a description of Halcomb’s music that sounded like poetry, “the high lonesome sound.” As Cohen made clear, it wasn’t isolation that made Halcomb unique but a combination of startling talent and, when Cohen met him, no real career as a musician or even much of a local reputation. Halcomb played music to please himself and, when he played in church, his fellow worshippers.

If you know what to listen for, you can hear the high, straight sound of lined-out hymn singing in Halcomb’s voice and what he learned from Blind Lemon Jefferson records and other blues recordings in his rhythmic playing. But even if you don’t, you can just listen. Halcomb’s sound is simultaneously heady and blue, a stop-you-in-your-tracks kind of contradiction. Cohen described it as somehow “ancient” and “avante-garde.” Halcomb’s best performances sound like they are trying to carry the weight of all human experience. They make you feel awake and alive, open to the pain and also to the glory.

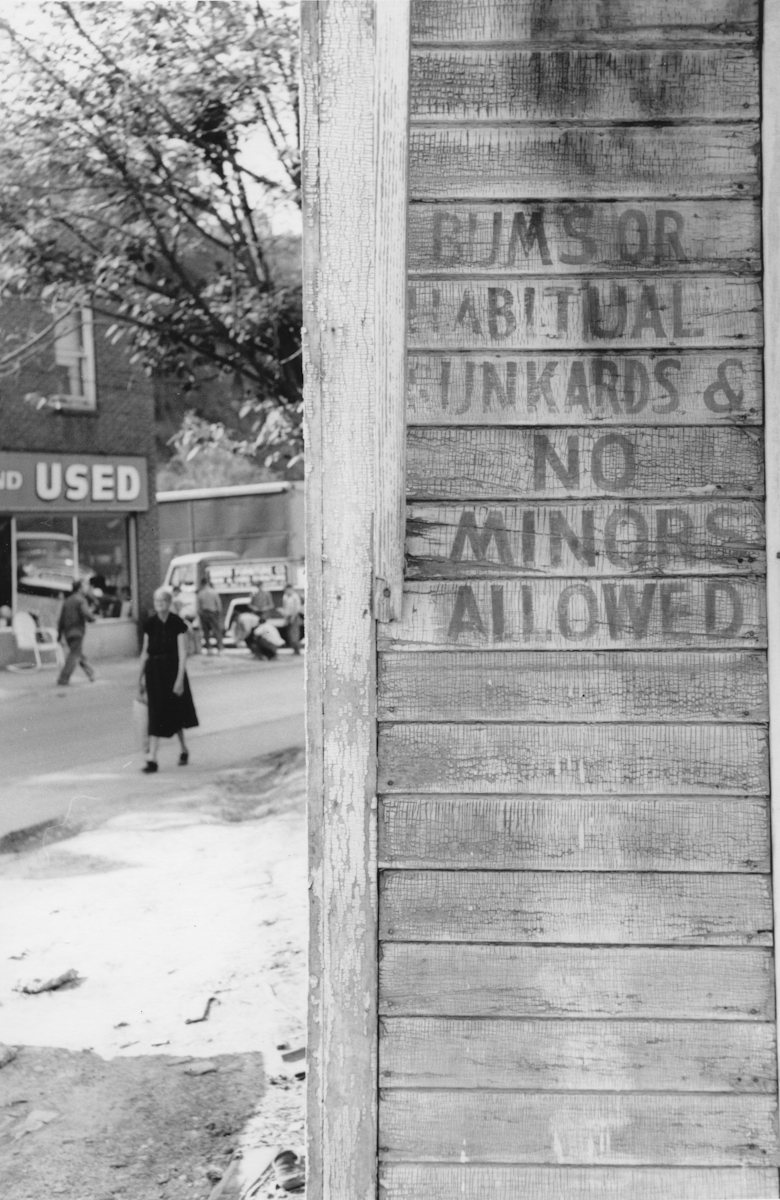

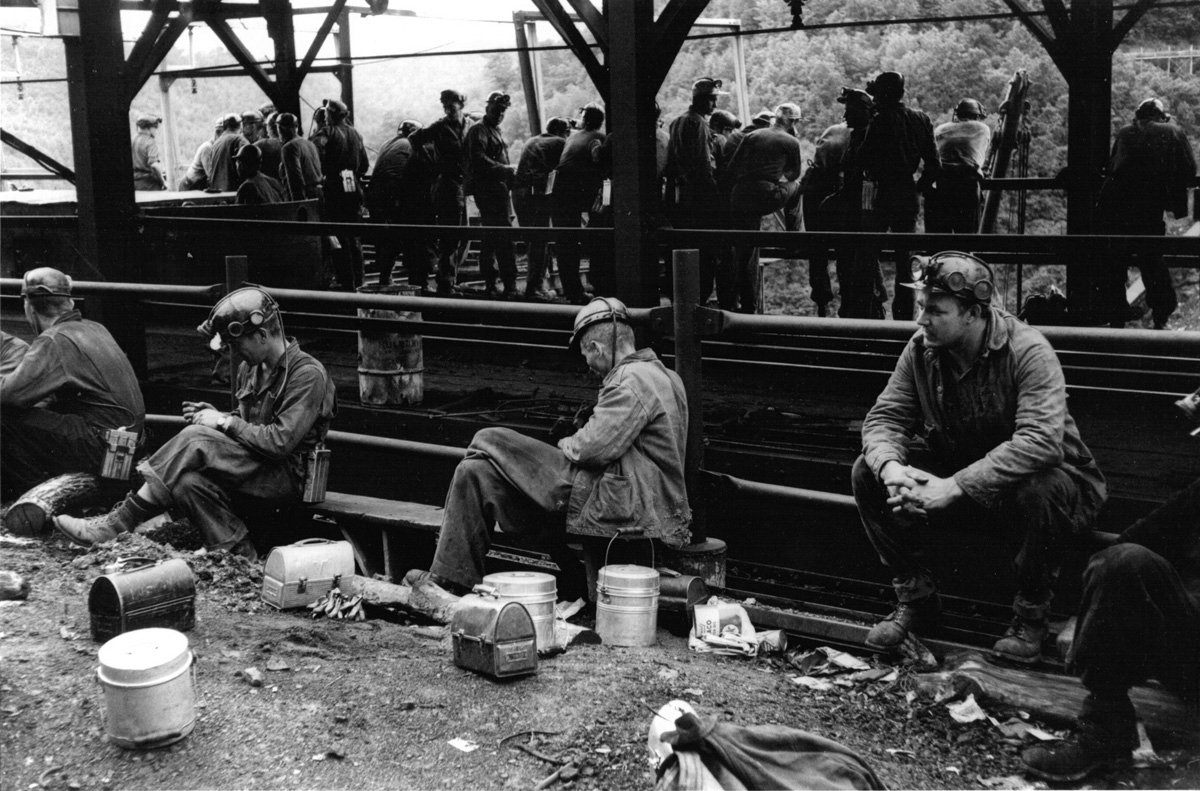

Cohen almost always took photographs of the musicians he recorded, portraits and performance shots. In eastern Kentucky, he also made pictures of mines and mountain roads, wrecked cars and railroads, coal camps and commercial signs, the interiors of homes and small-town streets, kids and dogs, miners at work and at home, farmers plowing their fields, and worshippers in church praying, singing, playing guitar, and falling down with the Spirit. He wanted to be able to show people elsewhere the look and feel of the place the music came from, its context.

Halcomb’s best performances sound like they are trying to carry the weight of all human experience.

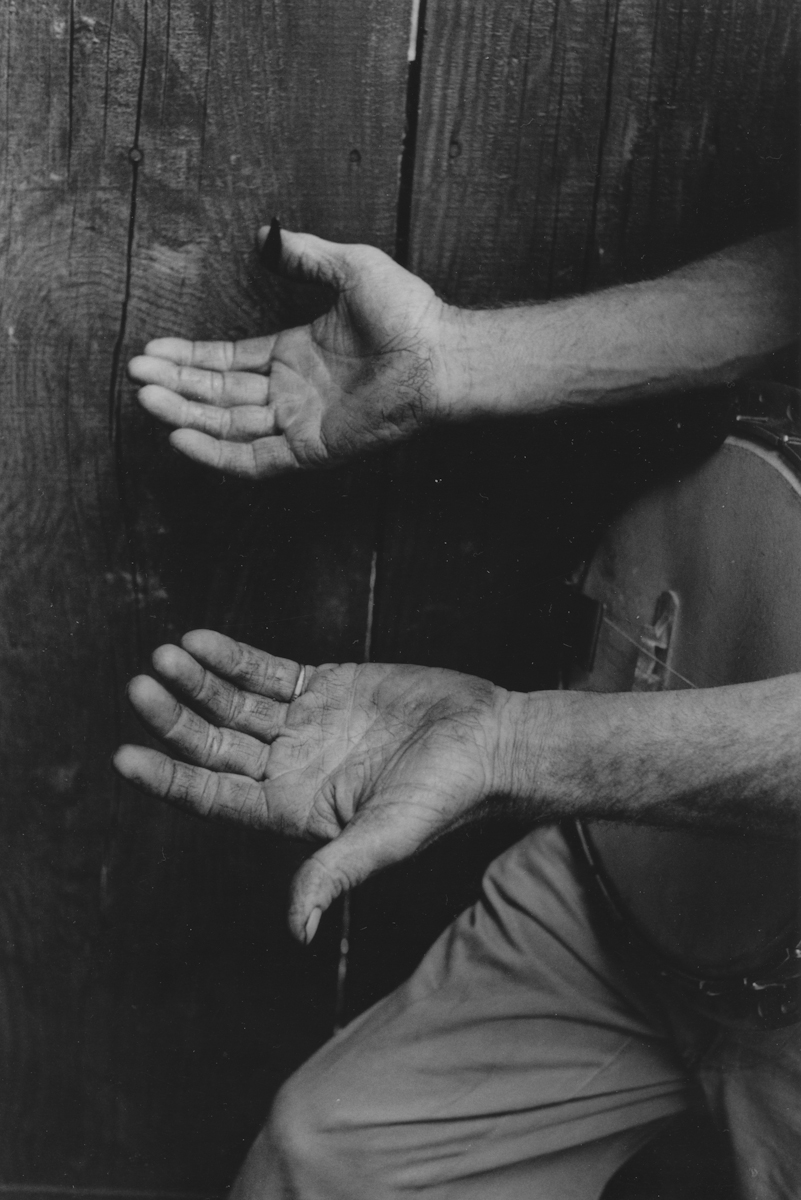

Some of Cohen’s images—Halcomb’s cracked and dirty hands held out for the camera, circus posters pasted on a wood frame building whose poorly applied whitewash has worn off in stripes, the interiors of simple homes, the exterior of a barber shop—reproduce the look of photographs made by Farm Security Administration photographer Walker Evans during the Great Depression. Others employ Robert Frank’s off-kilter compositions and perspectives to suggest intimacy and movement, the view between a mule’s ears, a miner bent over in a short seam, a teenage girl with a hoe walking in a plowed field in high heels. Some photographs even evoke sound, a chord pressed into a guitar or banjo neck, lips shaped around a lyric, or a thumb hitting a string. Halcomb, wearing glasses and also often a hat, has a craggy and interesting face and usually poses with a guitar or a banjo. In a more spontaneous shot, Halcomb climbs a hill with a brown sack of supplies, his free left hand swinging wide as paths and fences cut diagonally across the slope to form a series of switchbacks behind him. The photo is so alive that every time I look at it I expect Halcomb in his overalls to keep walking upward and out of the frame.

Yet Cohen, an artist for whom experience was everything, was not satisfied. Neither the recordings and photographs he brought together in that first Folkways album, Mountain Music of Kentucky, nor an event he helped arrange, Halcomb’s 1961 performance at the Chicago Folk Festival, quite conjured what Cohen felt when he was with Halcomb in Daisy. Because Cohen wanted others to be filled up too, he decided to make a film. In 1962, he borrowed a camera without sync sound capability from documentary filmmaker Albert Maysles and convinced Joel Agee, the writer James Agee’s son, to come along to Perry County for six weeks as his assistant. They set out in August in a Volkswagen van.

Cohen wasn’t the first folk music collector to document old forms of music this way. Collectors had been shooting footage of people singing and dancing in what were understood as “folk” styles since the early twentieth century, and Cohen’s brother- and sister-in-law Pete Seeger and Toshi Seeger started making films in the early 1950s. The website Folkstreams.net provides access to many examples of this kind of documentary work, including The High Lonesome Sound (1963). But just like he did with his still photography, Cohen transformed what had been in the hands of others a more “objective” documentary style into a subjective and intimate project. Fusing his photographer’s eye and his music collector’s ear, he created a new kind of genre, more art film than folkloric study, that paved the way for future filmmakers including Lester Blank and Elizabeth Barrett.

In The High Lonesome Sound, Cohen wants us to feel as well as see and hear what life is like in Halcomb’s eastern Kentucky world. Somehow, his inability to record sound and image together frees him to experiment in both registers. A few awkward patches of voice-of-God narration set up the context, but otherwise Cohen constructs a lush soundtrack. People sing and play guitar and banjo, the tinny speaker of a radio blasts a hit, insects and birds chirp and screech, train cars clack, ministers with thick accents preach and pray, and worshippers scream with the Spirit. Despite or perhaps because of the disconnect between the sound and the images, what you hear deepens the immediacy of what you see.

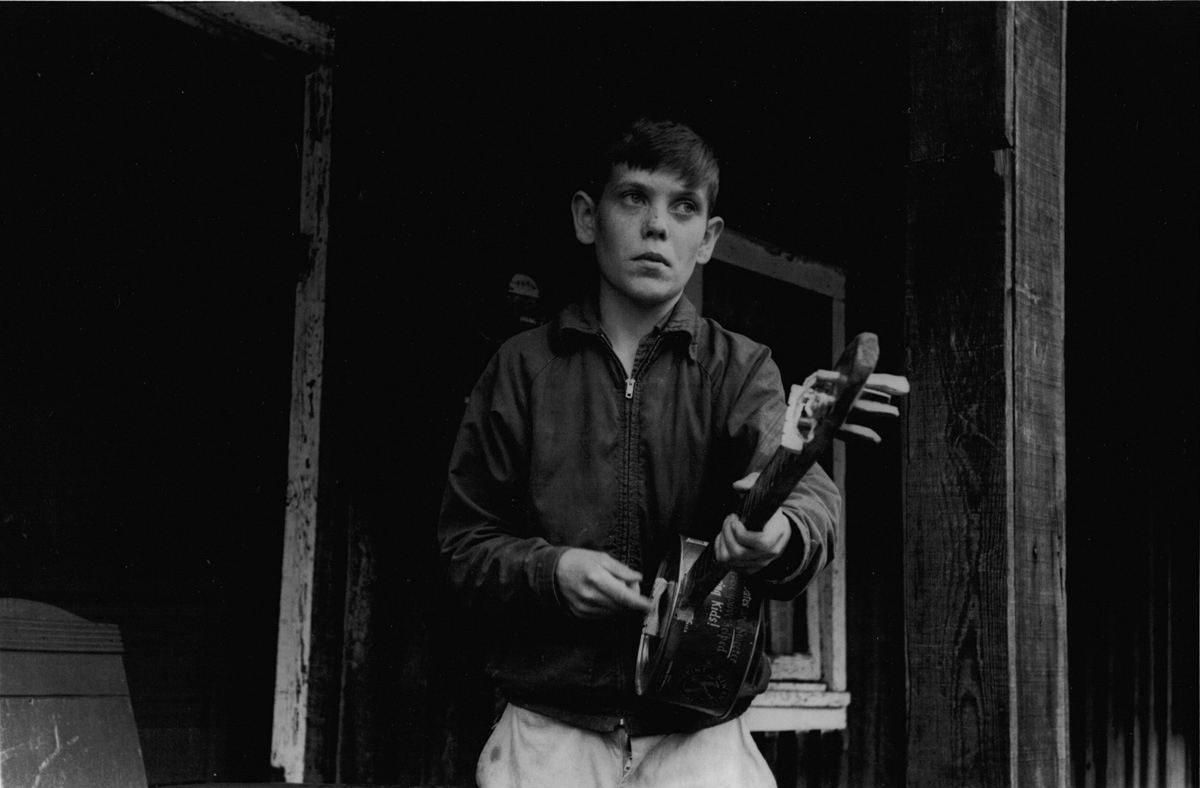

Cohen has a brilliant ability to find the art in casual gestures. In a Holiness church, a little girl reaches her little hand up to a tambourine on the edge of a dais and plucks out her pacifier.

Outside Halcomb’s house, another little girl dances with a flyswatter as Halcomb hoes his garden. White patrons dance, “twisting the night away,” as a band covers a popular song in a bar. The sound of barking gives way to banjo picking as a light dog and dark dog chase each other and play behind a hand-driven water pump in a misty yard. As Halcomb performs “Across the Rocky Mountain,” the camera pans around the interior of the Halcomb family home. The neatly made-up twin beds with their matching spreads, the bright brocade curtains at a window, the patterned linoleum “rugs,” and the carefully pressed clothes hanging on nails on the wall deploy cleanliness like a shield that keeps stereotypes at bay.

Often, Cohen lingers on the landscape: the bruised pleats and folds of the southern Appalachian mountains, the close-in view in the hollows, the wide vistas from the ridge lines, thick forests giving way to small fields and gravel roads and, more rarely then, the raw wounds of strip mining. Everywhere, fog and mist and clouds are in motion, rolling across the hills and the trees and the sky. Together, these images become a metaphor for near and far, a place that is a part of and yet also different from Cohen’s modern world.

I do not know what Roscoe Halcomb grew up believing. All I know about him comes from Cohen’s art, documents Cohen saved, and the research of historian Scott Matthews. That evidence suggests that while Halcomb enjoyed playing music, he never really wanted to be known as an artist. As Halcomb told it, he learned to play the banjo during “pretty hard times”: “There wasn’t hardly no way for a man to get work, so I asked God to give me something that I could do—that I could make a little money. . . . Twelve months from the time I started playing with this old fiddler I’d learned I guess about 400 tunes and could sing practically every one of them.” But as he later confessed, “I never did feel that I was a musician—never could make anything of it. Bill Monroe would chew me out every time I’d get with him, because I wouldn’t quit work.”

In later years, as criticism of music collectors “discovering” people like Halcomb mounted, Cohen got defensive. “If I hadn’t found him in Daisy, Kentucky, in 1959, there would be no record of his music. He never had the desire to record, go on radio, or perform in public.” That was not quite correct. Halcomb talked about playing dances as a younger man, and Cohen documented him playing in church. Nothing in the record suggests Halcomb was reluctant to play for John Cohen’s tape recorder. As Halcomb wrote in a letter Cohen saved, “John, you asked me about what I thought about music. . . . You know that I love to play when some one come around. I love to go to church, too. I try to please everybody. I think it is good to suit all crowds if I can. . . . I always try to.” The only time Halcomb ever seems to have refused one of Cohen’s requests occurred when the young man was shooting film. Then, as Matthews has argued, Halcomb got frustrated by the awkwardness of a process in which Cohen made him perform everything twice, once for the tape recorder, and then again, in exactly the same way, for the film camera.

As Halcomb told Cohen repeatedly in interviews and also in letters that survive because Cohen kept them, what he most wanted was steady, paying work. Since in his experience music had not provided this, he looked elsewhere. Often, Halcomb was depressed, not because he had not found fame as a musician or was having an existential crisis but because he was out of work. And the problem was not just a recession felt across coal country. After decades of what Halcomb called “hard labor”—work in construction, coal mines, and lumber mills—his body was broken. As he told Cohen in 1964, “I love to work whenever I’m able. . . . I thought I was getting better, but it was just a thought. I wasn’t. That’s what got me worried. . . . Man just as soon have his brains shot out as to be in that condition, the way I feel. I don’t know whether you know how I feel or not, but it’s rough. It’s a rough life.” Halcomb simply did not share Cohen’s artistic ambition or his sense that art was the measure of a meaningful life.

In letters Cohen published in his book The High and Lonesome Sound: The Legacy of Roscoe Holcomb (2012), the man who signs his last name Halcomb talks repeatedly about two related subjects, work and money. He thanks Cohen for sending checks. He urges Cohen to set up gigs. And he asks Cohen to send him records he can sell or to advance him money on future gigs. A letter dated March 19, 1964, is typical: “John, get all the work you can for me for I haven’t worked any at all since I came home. Things are looking very bad round here. So when you send my ticket [for travel to an upcoming concert], send a little extra money for food and I will make it up to you.” Sometimes he also describes his poor health to explain why he is out of work. Halcomb was still writing these letters in the early seventies, recruiting Cohen to help him copyright his version of the song “Single Girl” so that he might earn some money from it, after Michelangelo Antonioni used it in the film Zabriskie Point.

Cohen understood as well as anyone how little money most folksingers made, and he never suggested to Halcomb that he could make a living playing music and selling records. Because he loved Halcomb’s music and knew something of his need, he tried to help. Periodically, he arranged paying gigs or put people organizing festivals or concerts in touch with Halcomb. At other times, he traveled to Kentucky to meet Halcomb and travel with him to shows, or he arranged for others to help the older man navigate buses, trains, and planes. Cohen also played a role in organizing a March 1966 three-week tour across Europe in which Halcomb, Ralph and Carter Stanley, the New Lost City Ramblers, and others performed. Halcomb made $750. An article in an eastern Kentucky newspaper tipped off the local welfare office, the Hazard, Kentucky branch of the Division of Public Assistance of the Kentucky Department of Economic Security. Halcomb ended up losing his place in the Work Experience and Training Program, known locally as the Happy Pappies, a program which put unemployed fathers (Halcomb had stepdaughters) to work on jobs like cleaning roads of trash, repairing the homes of elderly local residents, dredging streams, and other odd jobs. Cohen tried to help Halcomb get his position back. He wrote letters on Halcomb’s behalf and even traveled to Hazard to speak to welfare officials in person, but nothing helped. Halcomb would never hold steady employment or assistance again. When he died in 1981, he was destitute.

In 1978, Halcomb took the bus to New York City to perform at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. According to Cohen, a “spasm of coughing” made it impossible for Halcomb to finish the Old Regular Baptist hymn he was singing, and he left the stage. The audience, stunned and confused, did not applaud. It was Halcomb’s last show.

All these years later, that damage is done. The art survives.

Across the more than two decades that they knew each other, Cohen gave the older musician what he wanted Halcomb to have, and what he wanted for himself, an enduring reputation as an artist, what we might call an afterlife. But that reward came in a world distant from Halcomb’s eastern Kentucky home. What Halcomb seems to have wanted was a life, which he understood as secure and steady employment that would enable him to provide for his family where he lived. That someone who could play and sing with such haunting intensity would not want to be known for his talent, would in fact trade it away in a heartbeat for a steady job with steady pay and some measure of economic security, was not something that Cohen, who had rejected that kind of life, could grasp. If Cohen had not been so focused on the art, both his own and Halcomb’s, he might have been able to more clearly see the man. Roscoe Halcomb might have remained in the Happy Pappies and had an easier last decade. But the rest of us would have missed out on the high and lonesome sound.

All these years later, that damage is done. The art survives. And so do the challenges Halcomb faced securing well-paying work, affordable healthcare, adequate disability payments, and fair royalties. It’s too late to discover what Halcomb might have done in a world in which he had real choices. But it is exactly the right time to build an America that provides every one of us the security to dream.

I never did live up to John Cohen’s challenge. Travel for work was nearly impossible for me as a single parent. I gave up on my foolhardy quest to track down and watch all the film footage shot in the rural South before the invention of video, the project that had led me to my first meeting with Cohen. But with my young daughters in tow, I did make it up to his place near Putnam Valley for a few days in 2008. When we arrived, he gave us a tour of the farmhouse and the various outbuildings and barns. Along the way, he showed us the storage cabinets that held his negatives and prints and reels of 16mm film and the drawers full of drawings and other artworks. The historian in me noted that the barn exposed those archives to four seasons of New York state weather and the former hen house full of valuable old records leaked.

Later, we watched old footage of Halcomb and eastern Kentucky that Cohen later edited into a film. We looked through stacks of old photographs. We spent hours talking. And we unpacked a box of fabulous fossils that gave my girls hours of delight as they brushed the dust off and studied each one. At night, as I read them children’s books that had belonged to Cohen’s kids and tucked them into a bed, they told me that John’s house seemed like the kind of place stories happened.

The next day, we walked around the place, and John showed the girls how to skip rocks in the pond and then he cut the cattails. They did not need any help with the mud. When we left the next day to drive back to Virginia, those cattails and mud, along with some long sticks they had peeled the bark off of and turned into staffs and wands, filled the back of our station wagon. As we said goodbye, John Cohen put a worn and weathered first pressing of Mountain Music of Kentucky in my hands and urged us to return.

A few weeks later, I was in DC conducting research at the Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. I told Todd Harvey, the librarian I was working with, about Cohen’s collections and the leaking barns and urged him to contact John. In 2011, Cohen moved those precious materials to their vaults in Washington. The archive at least is safe.

I saw Cohen several more times before he died in 2019, and we never did stop arguing about the inequality at the heart of his documentary work. But now that he is gone, I am tired of my doubt. There is no way to predict what the future will make of either artist, Cohen or Halcomb, or the relationship between them, but one thing seems clear. Because they met, we have this beautiful work. What we make of it is up to us.

This essay is part of our Shutter photography series.

Grace Elizabeth Hale is Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and a 2018–2019 Carnegie Fellow. She is the author, most recently, of Cool Town: Music, Art, and the Promise of Alternative Culture in Athens, Georgia (University of North Carolina Press, 2019). She has written for the New York Times, Washington Post, American Scholar, and Southern Cultures. She is currently working on “The Lyncher in the Family,” a book about her grandfather, a Mississippi sheriff, and white Americans’ inability to reckon with the history of white supremacy. Hale is codirector, with Lauren Tilton, of Participatory Media, a digital public humanities project on collaborative media-making in the 1960s and 1970s, and a collaborator in the University of Georgia’s Athens Music Project.

Header image: Roscoe Halcomb and John Cohen play together at the Berkeley Folk Festival, Berkeley, California, 1962, via Getty Images.