I have lived on a small farm in southern Vermont for the last thirteen years. One year, it simply did not snow, and the low-grade environmental anxiety I’d been swallowing blossomed into something ferocious, blocking my imaginative impulse. I felt as though I couldn’t write fiction anymore. I poured my energy into becoming an environmental essayist and climate journalist and spent the last six years writing pieces for The Guardian. Even though my desire to write fiction has returned, environmental writing is the work that matters most to me.

Once, on assignment in Florida in 2022—where I was writing a piece on road ecology—I met Carlton Ward Jr., a seventh-generation Floridian working to protect panthers and Florida’s wildlife corridor. Ward has maintained a palpable connection to the landscape and regularly traipses through alligator-heavy wetlands and cattle ranches. While in the field with him, I observed his sincere, years-long relationships with ranchers, scientists, and conservationists. Simply put, his willingness to remain where he was planted and leverage his expertise results in bipartisan conservation work with moving depth and efficacy.

Writers often talk about avoiding “parachute journalism,” the notion that western and big-city journalists plunge into unfamiliar, often rural, communities to report a story. In its worst forms, it can feel extractive, like a harvest—a nonreciprocal action that lacks deep understanding and risks missing important nuances and enforcing stereotypes in reporting. I know that I have done this, too, even with good intentions, because, in truth, how many places does an ordinary person in 2023 know intimately, and with convincing clarity?

After following Ward through the backcountry of Florida, I asked myself: What’s my real home? What place do I know deeply? What place wouldn’t be parachute journalism? While I’ve lived in Vermont for over a decade, I am not native or even remotely “at home” there. My first thirty years were spent in eastern North Carolina, particularly Rocky Mount and Atlantic Beach, both part of—or near—the Inner Banks region of the state: three thousand miles of marsh-heavy coastline.

People easily recognize the Outer Banks, particularly those from out of state who have visited Nags Head or the Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kill Devil Hills, where the brothers tested their glider on a large dune in 1903. The Outer Banks is full of lore—shipwrecks, treasure, Blackbeard dipping in and out of the waters surrounding Ocracoke. Party- and vacation-friendly, and exceedingly photogenic, it is easy to love.

In climate change reporting, the Outer Banks are iconic. Reportage set there often shows second homes on stilts being claimed by the ocean. These scenes are tragic, as the loss of a second home is the loss of a significant investment and perhaps generations of memories, but second home loss is not always the most meaningful example of the steep costs of climate change. As we know, privilege can better absorb risk. Sometimes, this view of climate change, like the overused images of polar bears, obscures the suffering of entire towns and populations.

While the Outer Banks are easily demarkated—residing on barrier islands, impossibly small slips of sand that snake along North Carolina’s coastline—the Inner Banks are more loosely defined. The term Inner Banks is, at its heart, a marketing tactic, a way of packaging a region in the state so often ignored. They are essentially the inland coastal region of the South, which includes the counties that touch the tidal waters that move between the Outer Banks and the shore of the state.

Wondering if I might establish a deeper creative relationship with my place of origin, I decided to drive through the Inner Banks in January 2023 after visiting my parents in Raleigh. I began in Beaufort, a historic harbor town located on the Beaufort Inlet and tidal Taylor’s Creek. It’s the town where I’d likely live if I hadn’t married a Vermont veterinarian. It’s the town where I’ve eaten seafood dinners out since I was in elementary school. It’s where I fell in love with sailboats and kept my own boat the first spring I was a boat owner. When I step into a coffee shop, I might still run into an old high school boyfriend, like I did last year.

There’s a part of me that still hopes to find myself living in one of Beaufort’s historic houses one day, hosting a friend for a beer on the front porch, though, truthfully, I know this fantasy is fraught. The historic houses in the center of Beaufort’s downtown are prohibitively expensive for a writer. And besides that, climate science predicts at least a foot of sea level rise in the next thirty years and continued sunny-day flooding. Beaufort, like Bath or New Bern, is an Inner Banks town with both a residential and a seasonal culture, and a mix of social classes, with fine dining options and marinas full of sport-fishing yachts, as well as middle-class folks and those below the poverty line who support the hospitality industry or who fish.

The Inner Banks are composed of towns that even longtime residents of North Carolina haven’t visited, like Swansboro, Gumneck, Oriental, and Sealevel. These towns don’t draw hordes of tourists or their dollars, and the lower tax base makes climate resilience and disaster repair more challenging. Beach nourishment and flooding repair may qualify for federal dollars but will likely remain largely the responsibility of locals in years to come.

I’ve long included Inner Banks towns in my fiction—the Great Dismal area and Lake Mattamuskeet in Birds of a Lesser Paradise, and Alligator in How Strange a Season. To me, there’s something underdiscussed about lives in small towns. In western media and literary fiction, life in a southern locale often takes on an exaggerated and outdated quality. (A southern writer friend of mine once said, “If I have to read another story about Mee-maw eating biscuits on the front porch . . . “)

I know—I feel—the general landscape of an Inner Banks town, the quietude, the flat highways surrounded by recently logged loblolly pine, the McDonald’s, the Bojangles, the bygone Exxon station with the bathroom you don’t really want to use, brick churches with white steeples, a tackle shop. Hog trucks on the highway, long metal chicken houses in the fields just off the road, a Nahunta billboard. These are not all second-home towns. These are places where you can still find a little wilderness, even if it’s now owned by a paper company.

Like any small town, the ones that compose the Inner Banks have their specificities and nuances, their joys and problems. Eastern North Carolina’s Albemarle Peninsula supports the only known population of red wolves in the wild—scientists believe only fifteen remain. Cecil B. De-Mille’s family, as well as the Miami Heat’s Bam Adebayo, come from Little Washington, where a Union cannonball can be found in a local lawyer’s office. Elizabeth City hosts an annual Potato Festival to celebrate its agricultural heritage. Camp Lejeune, in Jacksonville, is a national center for amphibious assault training and has long battled a carcinogenic water contamination issue. In fact, a number of Superfund sites line the Inner Banks region, most caused from agricultural pesticide use and military pollution, like those at Camp Lejeune and Cherry Point. As I drive, I see fields of freshly picked cotton, as well as markers noting which strain of genetically modified crop is planted there. Military jets occasionally cruise overhead.

The low-lying nature of the Inner Banks makes the region especially susceptible to rising sea levels. Salt water will encroach on inland aquifers and alter tree composition and habitat. Rainfall during heavy precipitation events has increased 25 percent since 1958. Hurricanes and storms will strengthen, challenging towns like New Bern and Bath, which have already flooded numerous times, most recently during Hurricane Florence in 2018.

I drive from Beaufort north on US-17, then east on US-64. I want to make it to Alligator (population 244) before arriving in Norfolk, where I have an evening flight back to Vermont. The highway feels endless, the degraded, logged roadside monotonous, lit by the glow of omnipresent yellow Dollar General signs. The yard signs skew in an increasingly conservative direction; the number of tattered F——k Biden flags increases as I bear eastward. I see hog processing plants, chicken processing plants, shooting ranges, hunting camps. I pass newer houses on stilts, brick ranches in the process of being reclaimed by nature.

The closer to Alligator I get, the more often I encounter logging trucks. These sightings will come to define my memory of the Inner Banks drive. Companies remove an estimated five hundred thousand truckloads of timber annually from North Carolina, resulting in 44 million tons of carbon dioxide released every year, much of it in service of Europe’s pellet stoves. Nearly 2.6 million acres of North Carolina’s forestland—equivalent to 7.5 percent of the state—are considered “carbon sequestration dead zones” because of the short-term tree plantations used to feed the timber industry.

Not only is this rate of logging horrendous for the environment—with shipping factored in, it is dirtier energy than burning coal or other fossil fuels—but it strips the region of its natural beauty, and the visuals of this chronic ravaging are becoming normalized. The forests are alarmingly skinny and uniform. Logging for pellet stoves impoverishes the region for the people who live there, and for the species who have long called the region home.

I pull over at a gas station as I’m nearing Alligator. I’m admittedly depressed. I photograph log truck after log truck, their engines rumbling, dark clouds of smoke following them, splintered logs neatly stacked. The truth is that I do not know this part of North Carolina, and never did, despite living in the state for 30 years and attempting to conjure the sense of these small towns in my fiction. In both my journalism and stories, I have tried to set my artistic compass toward authenticity and honest representation. But there are always mysteries hiding in plain sight—the people you don’t have dinner with, the roads you’ve never turned down, the small towns a half hour from yours whose names you vaguely recognize. Places that might get swallowed by rising seas that are still important to those who live and work there. I know, as I head north toward Norfolk, that there is a beating heart I’ve missed in each place I’ve passed.

Every time I take a research trip, I hope to understand more about the places I’ve visited, and the people and species who make lives there: the fishermen drying their nets in Beaufort, the avocets hunting in the salt marsh. As I continue to write about my home state—in ways both real and imagined—I know that going deeper matters. When I feel bewildered—as I do, heading back to Vermont, a place that has never really felt like home—I feel myself setting an intention to learn more about North Carolina. If I aspire for my work to matter, and to circle emotional truth, I know there are more dirt roads I need to turn down, more folks I need to engage in conversation. There is always more I need to understand.

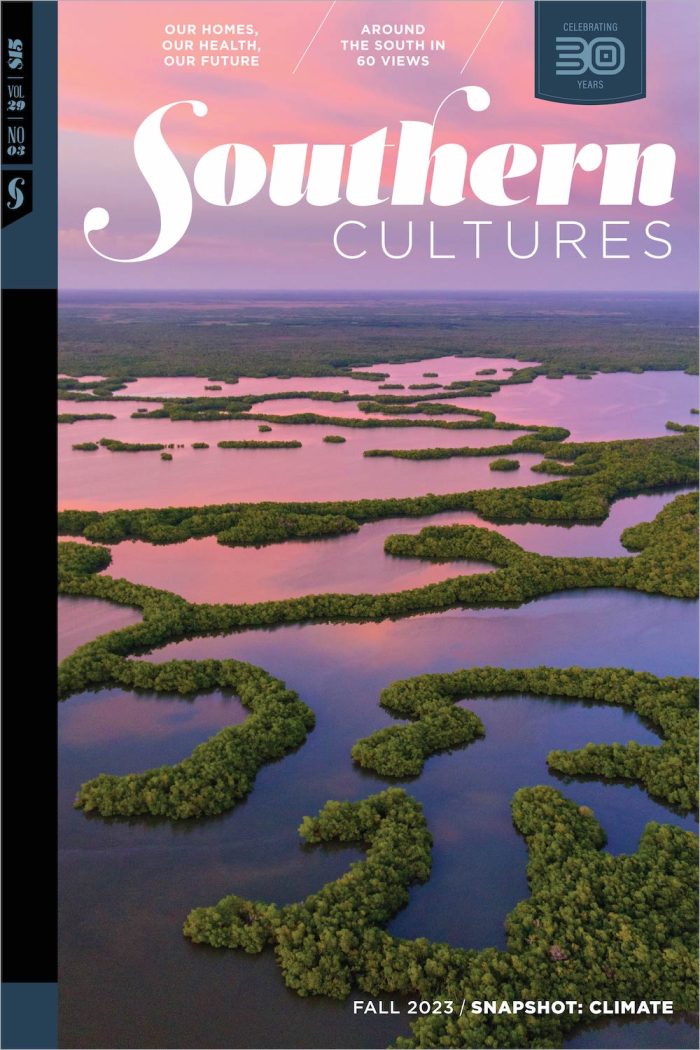

This essay appears in the Snapshot: Climate issue (vol. 29, no. 3: Fall 2023).

Megan Mayhew Bergman grew up in eastern North Carolina. She is the author of Birds of a Lesser Paradise, Almost Famous Women, and How Strange a Season. She is finishing a biography of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm and works as an environmental journalist with The Guardian. Bergman teaches at Middlebury College, where she also directs the Bread Loaf Environmental Writers’ Conference.