It was not supposed to end like this. On September 15, 1896, “Crush, Texas,” was supposed to be just another kinetic spectacle in a place replete with them. The name was a double entendre, both a cheeky allusion to the staged head-on train collision scheduled to take place there and an eponym for William G. Crush, the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad general passenger and ticket agent who devised it.

Nearby, Wacoans brimmed with excitement for the crash and devoured news about the “city of a day” built to host it. Disembarking at “Crush Station,” an audience of as many as forty thousand people found every desire accounted for: a dining room and thirty vendors fed them, and bandstands, freak shows, and shooting galleries entertained them. Turn-of-the-century infrastructure, including two telegraph offices, running water, and a jail, gave airs of permanence and control.1

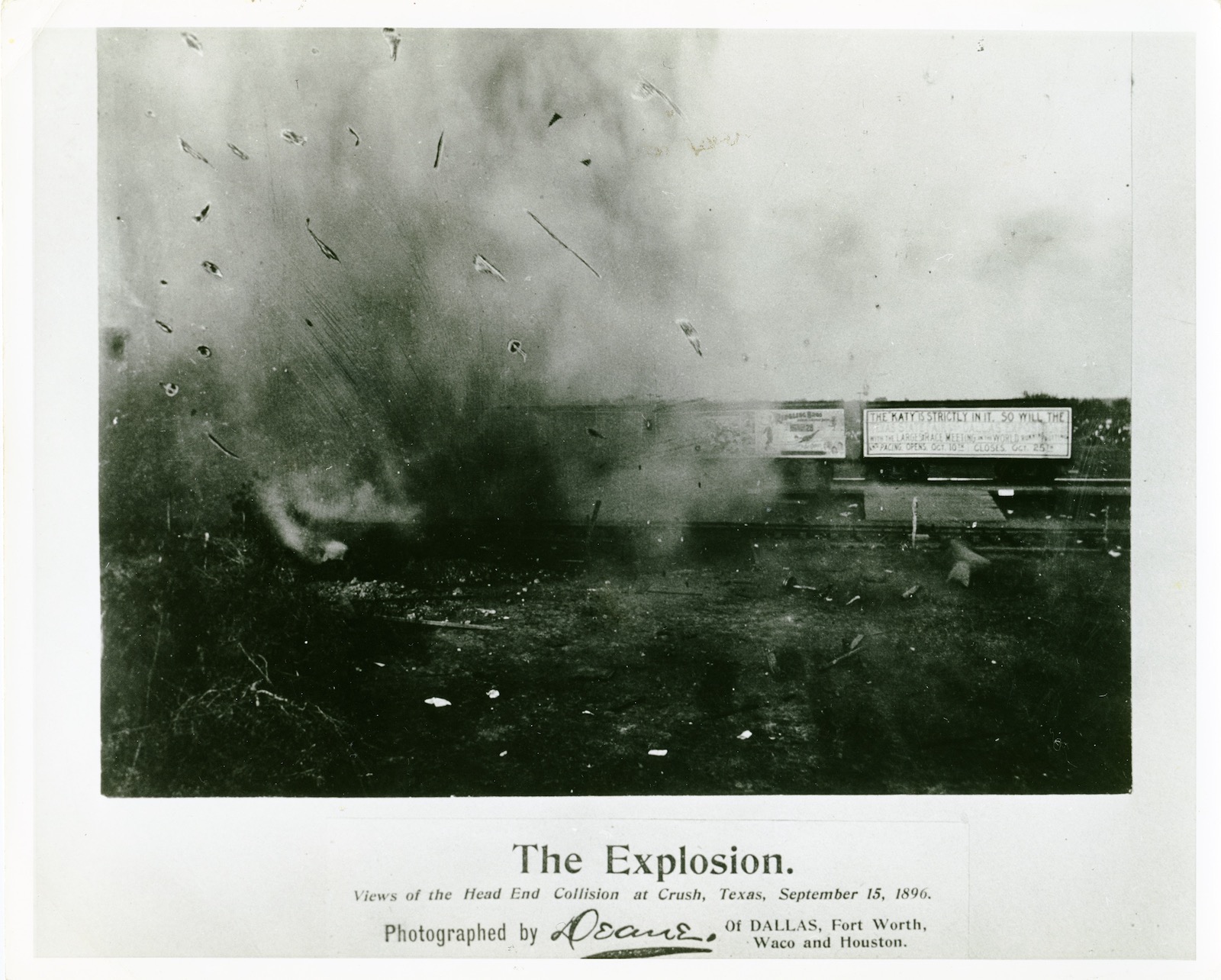

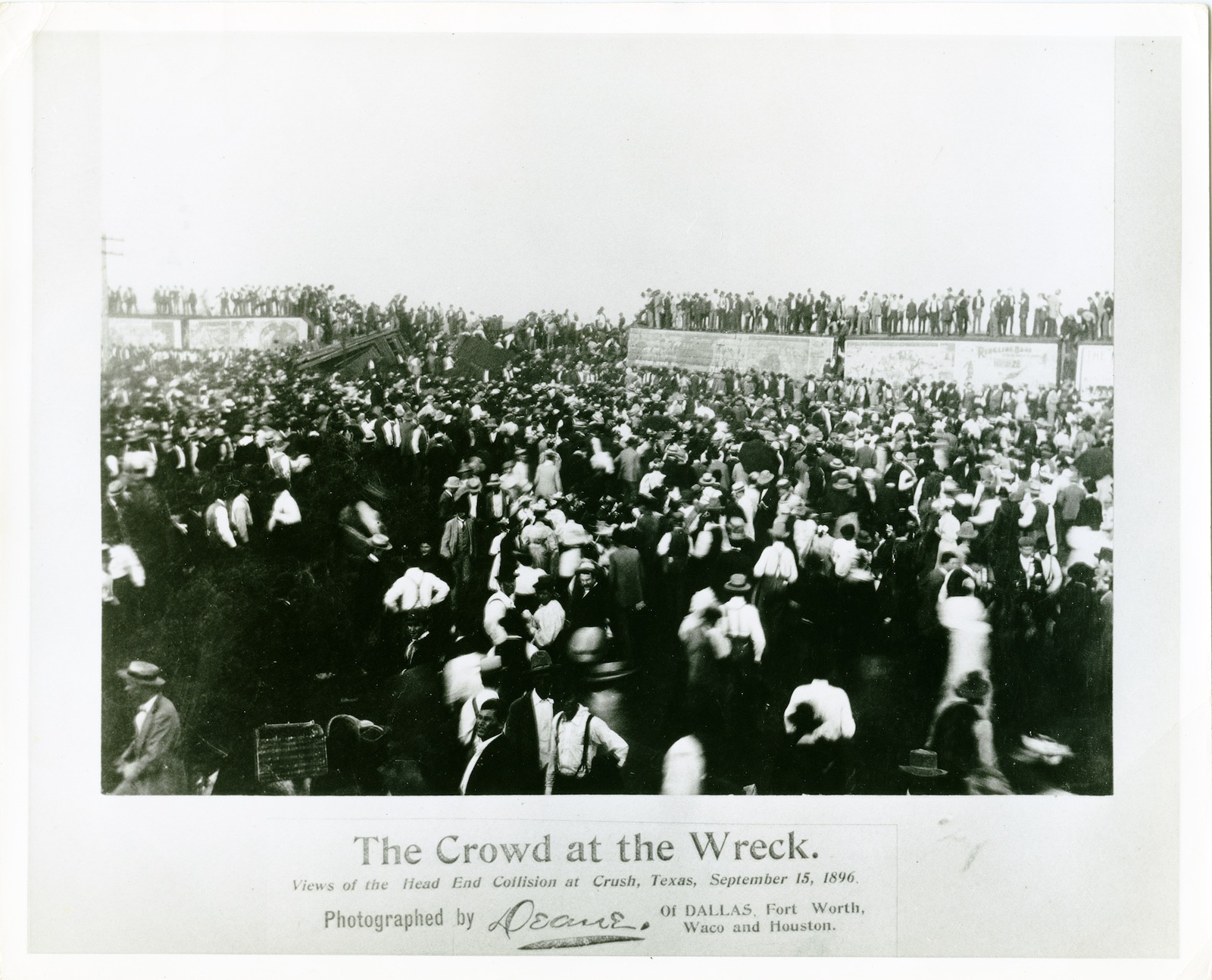

Shortly after 5:00 p.m., any pretense to order evaporated when the impact of the crash exploded the boilers of the two colliding engines. Pandemonium struck. Almost instantly, shrapnel leveled a dozen attendees, at least three of whom would die. The crowd, unfazed, rushed the wreck, dodging soaring debris to mount the cars and collect souvenirs from the wreckage. The frenzy fizzled fast. By 7:00 p.m., spectators like Maggie Dunn had returned to Waco, where they supped and “passed the time off very pleasantly” for hours. The rapid return to normalcy suggests that Crush was unusual but not exceptional. It was embedded within a thirty-five year history that produced a distinct sense of self and self-imagining in Waco—one where the kinetic spectacular was not only routine but foundational to the making of the New South.2

New South Modernity

The “New South” was a slogan, a critique, a vision, a movement, a creed, a period—symbolic, hyperbolic, mythological. In its most limited sense, the New South was a kintsugi worldview forged from pieces of a shattered past. Humiliated by a doomed bid for a slaveholders’ republic, boosters pedaled a model for an urbanized and industrialized South with diversified scientific agriculture. Despite their best efforts, however, the postbellum South continued to haunt the popular imagination as backward, prostrate, and stagnant. The oppressive climate seemed to demand it, the drawl articulate it, the poverty guarantee it. “Diseases of laziness”—hookworm and pellagra—besieged southern bodies from without and within. Another disease, unfettered capitalism, sapped what little energy those bodies had, as railroads and extractive industries created a parasitic economy where productivity soared and standards of living froze. In the decades after Appomattox, journalists, academics, reformers, and photographers went South and portrayed the region as “pre-modern,” a reflexive vindication of the northern way of life.3

Modernity in the form of urbanization and industrialization would not arrive in the South until the New Deal and World War II. Yet, modernity is more than economics; it is an ensemble of (at times contradictory) technologies and ways of seeing the world. For this reason, C. Vann Woodward urged historians to search for a modernity rooted in a new southern sensibility. Recovering this requires stripping away expectations set by northern development and mores. Doing so brings into focus an endemic modern impulse to categorize, classify, and rationalize that extended to the rural corners of the New South. Modernity foregrounded the region’s most repugnant rituals of Jim Crow, as white southerners spliced up their populations to regulate movements that threatened to undo the unstable racial regime.4

An additional aspect of modernity remains overlooked in studies of the New South: speed. After the Civil War, Americans mapped increasingly rapid cycles of destruction and creation onto their cultural and political landscape. Quickening motion—of technologies, of politics, of people—defined the age’s aesthetic. This same obsession was evident in the South, where it took on a decidedly southern cadence. It can be difficult to see motion as a defining feature of the New South when focusing on the period’s representative cities like Richmond, Charleston, and Atlanta. There, the omnipresent metaphor of springing back to life occludes the significance of literal motion in everyday existence. These damaged cities provided easy fodder for local boosters like Atlanta’s Henry Grady, who tethered ideas of a “New” industrial and urban South to images of a phoenix-like rebirth from the war’s ashes. Yet, as Woodward warned, urban boosters left a domineering presence in the archive that threatened to set historians’ agendas, conflating the metaphors of their programs with the experiences of regular postbellum southerners. While historians have reappraised the New South as a period and way of life beyond boosterism—querying what it was like to live in this volatile era and how the Civil War set the trajectory of these developments—the settings and characters in these updated histories remain largely the same.5

Atlanta had a foil: Waco, Texas. Waco, too, was a postbellum tabula rasa—but of a different sort. One hundred miles from everywhere, in 1860, it was a small wooden village of eight hundred people that exploded after the Civil War to become a midsized city and capital of nineteenth-century spectacle. Untouched by war, Waco was free of the white noise of boosters and destruction. This remote western outpost of the New South illuminates how mobility was more than a booster metaphor for regional regeneration.6

Here, a kinetic South comes into view. The war forged a fascination with movement, structuring white Wacoans’ perceptions of their natural, built, and social environments. The town teemed with motion for motion’s sake, which white residents touted, performed, and guarded as a racialized privilege. Movement became an organizing principle of life underwriting a particular (and particularly raced) conception of a new, modern South. In this light, Crush was an extreme spectacle of motion that was at once crescendo and coda to thirty years of constructing and celebrating a kinetic South.

Postbellum Migrations

With a population nearly 40 percent enslaved just four years after Waco’s incorporation in 1856, secession was all but guaranteed, and at least 60 percent of Waco’s white males enlisted. Despite strong ties to the Civil War, postbellum Waco had a weak Confederate culture. No monument ever adorned its square, and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC)—elsewhere the midwives of memory—mustered little support. Unlike much of the former Confederacy, Wacoans were not preoccupied by the war, though they were forever marked by it.7

A month before Appomattox, Waco’s mayor Richard N. Goode could still truthfully state, “We have not suffered very materially yet.” For soldiers and civilians of McLennan County, the shared Civil War experience was ennui. Via the lifeline of correspondence, soldiers and their families looked to each other for excitement neither could provide. When James Black lamented inaction, his wife responded, “You asked me to write all that takes place. Well, there is nothing interesting, funny, or dreadful occurring.” The war did not cause mass suffering in Waco as much as it paused its development. Residents were aware of this, for it was the key to their postbellum boom.8

After the Civil War, the South suffered extreme economic and psychic malaise. As a whole, the region saw a 30 percent loss in property, and agriculture languished until 1900. Texas was the great exception. With few battles, no starvation, and little disease, Texas became the nation’s premier postbellum cotton producer. A particularly weak Reconstruction made this fertile and pristine land all the more enticing for white southerners. Texas state politicians were adept at clearing the lowest bars of presidential and congressional Reconstruction while leaning on extreme racial violence to preempt any meaningful interracial politics. Nary a single Black politician rose to major office, and only fourteen joined the legislature. Regardless, President Ulysses S. Grant readmitted Texas to the Union in March 1870. After Democrats retook the governorship in 1874 under Waco lawyer, secession leader, and Confederate veteran Richard Coke, Reconstruction suffered a staggered death in the hands of omnipotent district judges overseeing local elections and appointments. As historian Carl H. Moneyhon noted, although Texas could have become anything between 1865 and 1874, it ended up a clone of its 1861 self: one-party rule over a cotton economy.9

McLennan County became a microcosm of these state trends. With limited wartime suffering, returning veterans resumed their studies, reopened shops, and replanted fields as if nothing had happened. By 1876, one city directory could proclaim that “as yet, ‘cotton is king.’” The county bounced back so quickly that, looking back from 1893, another directory boasted, “Whatever injury the war caused McLennan county her recuperative power was marvelous.” The same was true psychically, as local politicians ended Reconstruction swiftly after Coke’s election. As a result, McLennan County became one of many places in Texas where white southerners buckling under the weight of their historical choices could imagine starting anew on quasi-antebellum terms.10

State and county alike became a vast southern Eden for those ruined in war. Before Appomattox, white southerners delayed emancipation by fleeing to Texas to evade advancing Union lines. For them, this journey held promise; for the enslaved, anguish, as established kinship networks were destroyed. The radically different conditions of wartime resettlement set the trajectory for the future. White and Black population growth in Texas were near equal between 1860 and 1870. Afterward, hundreds of thousands of white southerners flocked to the one place where the distance between the Old and New Souths required no great cognitive leap. For the next two decades, Texas’s white population increased at twice the rate as its Black counterpart, as white resettlement underwrote a population surge of more than 1.3 million white to just over 305,000 Black people between 1860 and 1890. These demographic shifts ensured that postbellum visions of Texas prosperity remained predominantly white. In all, Texas experienced an unparalleled 270 percent population growth from 1860 to 1890; McLennan County, 532 percent; and Waco, 380 percent. By 1880, Texas led all former Confederate states in number of residents born in another state, with 606,428 total. Eighty percent of these were from the Deep South.11

McLennan County’s out-of-state population exceeded state patterns, topping 50 percent from 1870 to 1880. White Wacoans sacralized these shifts in the stories they told themselves. One UDC member recalled, “Waco was settled, chiefly after the Civil War, by people from the Southern States who had lost all their property through the War and came to the new land to build up their fortunes and establish new homes.” This was not Confederate mythmaking. Many veterans briefly returned home only to abandon their desolate land and start over in Waco’s cotton industry. Here arose a paradox: white southerners migrated for continuity, yet the extraordinary demographic changes they effected brought about a radical break with the past.12

Cotton’s Mobile Kingdom

The war set off a movement of peoples, machinery, technology, and products that would structure postbellum Wacoans’ perceptions, values, and self-imaginings for the next fifty years. Migration and development spurred each other in quickening succession. Once the Chisholm Trail provided immediate cash flow, white Wacoans rapidly ticked off all the markers of development: a bridge connecting Waco’s two halves split by the Brazos River; the telegraph facilitating a cotton economy; and a railroad by 1873. These developments and attendant mass migrations embedded movement as the cornerstone of their postbellum city in the white Waco imagination.13

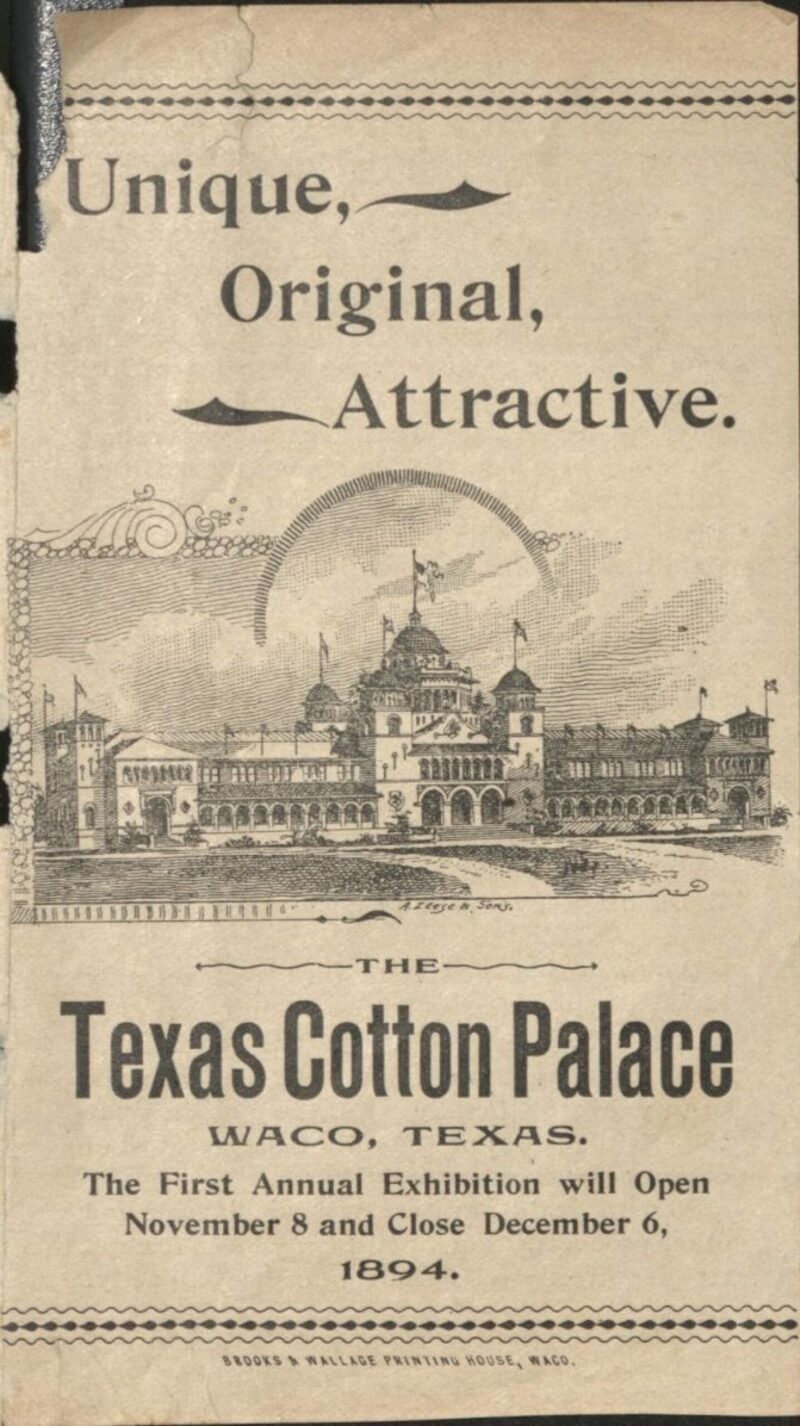

As Wacoans predicated progress and prosperity on kinetics, the movement of peoples became the great wonder of McLennan County. In 1894, Wacoans built a shrine not just to cotton but to the movement it incited. Inspired by the Midwest Corn Palace, businessman J. W. Riggins and his Waco Commercial Club capitalized upon Texas’s domination of the cotton industry to launch a Cotton Palace. The project had two functions. First, it attracted more attention, respect, migrants, and industry to Waco by providing “a photograph in miniature, as it were, of the capabilities of soil and climate.” Unlike fairs, which haphazardly displayed sample harvests, the palace cloaked the building’s very infrastructure in cotton. This quite literally suggested cotton was the foundation, pillars, and shelter for their society.14

Yet the Cotton Palace doubled as a story white Wacoans told themselves. Through themed performative narratives, the Cotton Palace allowed Wacoans to commemorate the historical migrations that produced their booming city. This was not remembrance so much as a twenty-nine-day performance. Riggins promised a deeper appreciation of cotton’s role in Texas through “a grand cotton jubilee, upon which occasion King Cotton shall be crowned king, and enthroned in an appropriate place.” It would commemorate the coming of peoples to till the land at the hand of King Cotton.15

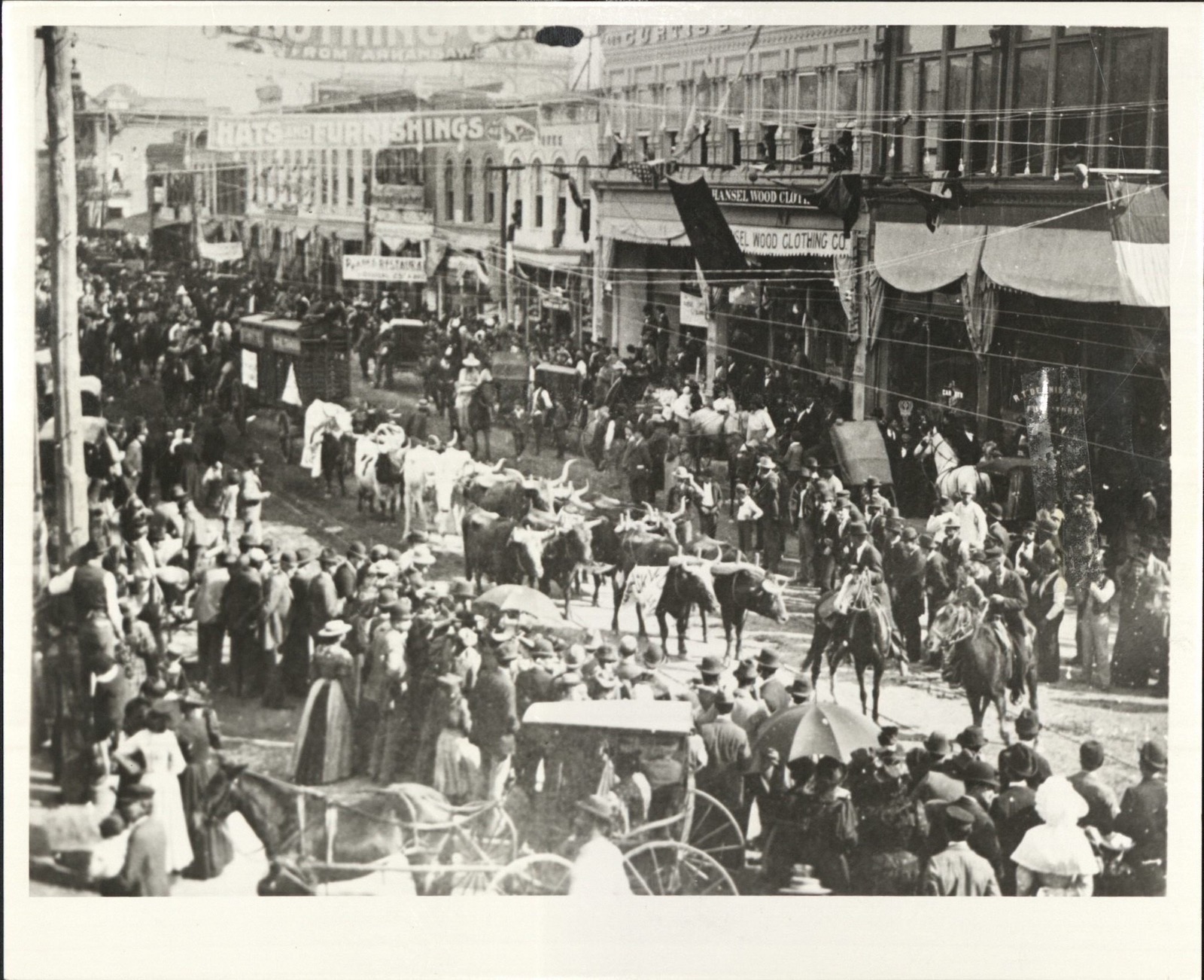

Riggins referred to it as a “grand King Cotton Carnival” in the medieval sense: a pageant laden with symbolism. The Cotton Palace opened with a parade on November 8, 1894. Streamers coated every building in Waco, “waiving [sic] a welcome to the monarch Cotton” personified, who led thirty thousand people from city hall to the baroque, quarter-million-dollar Cotton Palace. Wacoans repeated this pageantry daily. Organizers assigned a theme to each day that celebrated a particular demographic prominent in Waco’s past and present—including laborers, railroad workers, cowboys, bicyclists, and more—by giving them their own parade. As a result, every day, a particular group made its pilgrimage to pay tithe and tribute to what brought them to Texas: King Cotton. In the streets, white Wacoans manifested their perceptions of the literal movement that developed their city.16

Black Wacoans wanted little to do with it. A special “Negro Day” had lackluster attendance. After all, Black Wacoans had a different historical experience with mobility that began with forced wartime migrations with their enslavers. In the 1890s, white Texans continued to vie for control of Black Texans’ movements. The particularities of Jim Crow in Waco remain unwritten, but there is no reason to believe the city was exceptional. Legal segregation began in Texas in 1891. As elsewhere, it was no coincidence that it originated with trains, which tethered together ideas of physical and social mobility in the New South. Movement threatened a Jim Crow regime reliant on improvisation and custom as much as statute. The eponymous minstrel character was a traveler, significant in that Black Americans long understood citizenship as the inverse of their condition: unfettered movement. They would not find that in Waco. When they could break free and move, for many it would be with intention, away from the South during the Great Migration.17

Nothing captured the racialized privileges of movement more than the booming success of “Planter’s Day” that seemed a rebuttal of “Negro Day” in its celebration of Black Wacoans’ oppressors. The press described a late-night “Harvest Carnival Ball” that followed a parade adorned with $100,000 worth of cotton. The ball “opened with a grand allegorical march symbolizing the pursuit and progress of agriculture from the sowing of the seed to the reaping of the harvest, and the consequent wealth produced thereby for the glory of Texas.” Ceres, Roman goddess of agriculture, watched the procession from the five thousand–seat auditorium to the exhibition hall. Goddesses Flora, Harvest, Fruit, Texas, and Fortune marched with corresponding seasons and laborers. At the end, Ceres declared Cotton king and wed him to “Goddess Texas.”18

Inside the palace, visitors explored one hundred thousand square feet of cotton-related exhibits across two floors. Upstairs, women used local crops to create eighteen scenes of fantasy, mythology, and history. These carried no overarching narrative, which, paradoxically, imparted their meaning. Waco’s newspaper Artesia reported, “The combination of the beautiful with the historical; the mythological with the allegorical, forms a very pleasing transition.” Having these dioramas encircle King Cotton and Ceres melded disparate images into a tableau thematically united by the raw material comprising them. Cotton sat on a throne among his royal court. Nearby, Ceres looked down upon a miniature Cotton Palace that gave her offerings. Beneath Ceres, a floor map of Texas made from cotton and seed portrayed “Waco’s being the center and the only spot in Texas, the nucleus for all the railroads and the head of the Brazos navigation.” Together, the scenes were a reminder that Ceres and King Cotton gave Wacoans everything—and made Waco the mobile hub of Texas. In daily marches to the Cotton Palace and activities within it, white Wacoans reenacted this historical development in a kind of double pilgrimage.19

Waco Wellspring

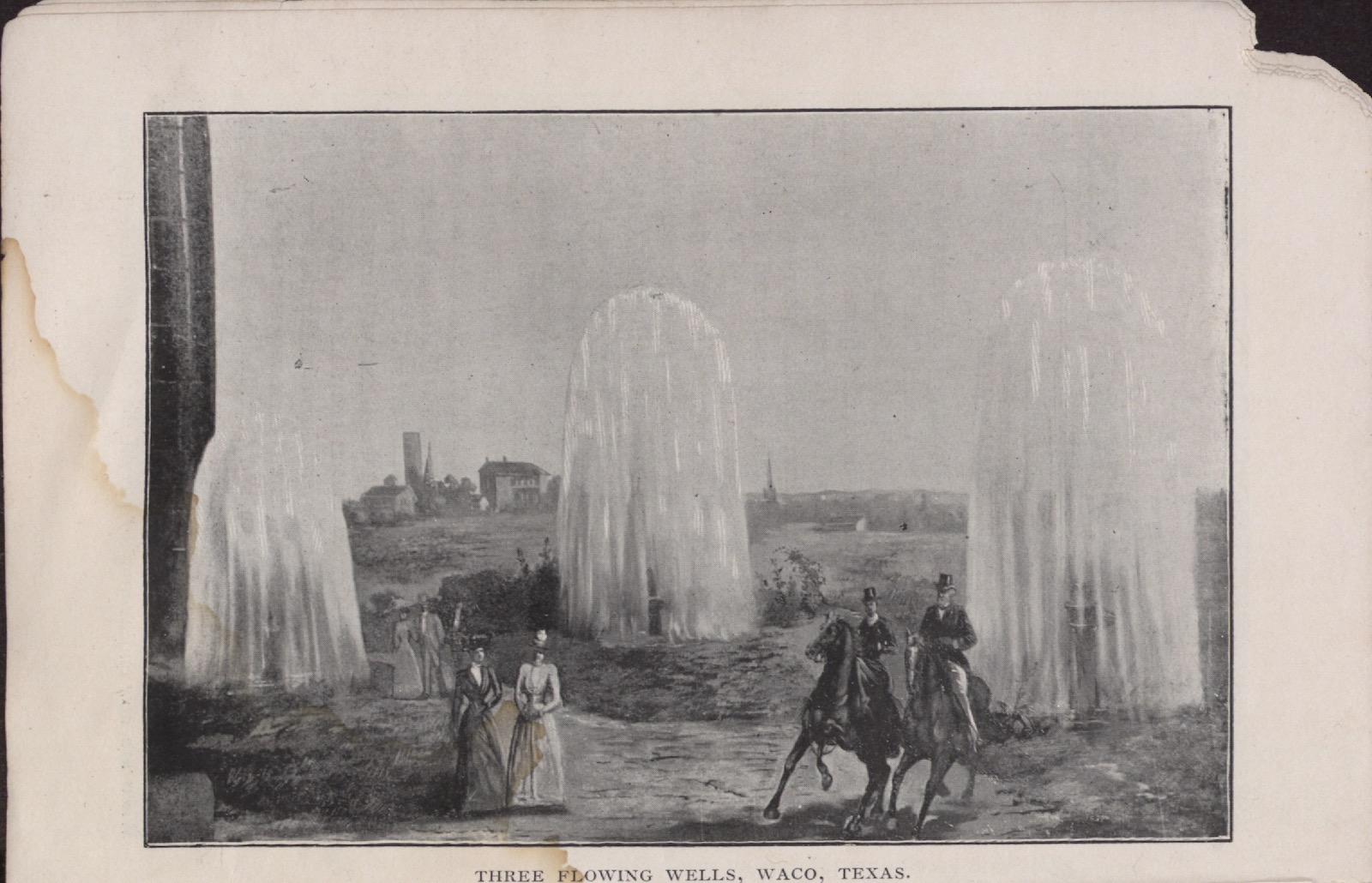

This same preoccupation with motion structured perceptions of everyday life, including Waco’s geography. When former miner Joseph Daniel Bell tapped the city’s first artesian well in March 1886, he set off a frenzy. Wacoans discovered that they lived atop a reservoir and created twenty-five wells, producing up to one million gallons of water daily. Wacoans obsessed over measuring the power of these reservoirs. An 1893 directory boasted that these “marvels of Waco” were commonly called geysers, “owing to the fact that the water is ejected at a pressure of 67 pounds to the square inch” from “a 100-foot standpipe, with a capacity of 175,000 gallons. Through an inch and a quarter ring nozzle this water can be thrown 108 feet vertically.” This made for rich imagery and even richer uses: to Wacoans’ delight, the wells powered machinery and elevators and flushed gutters.20

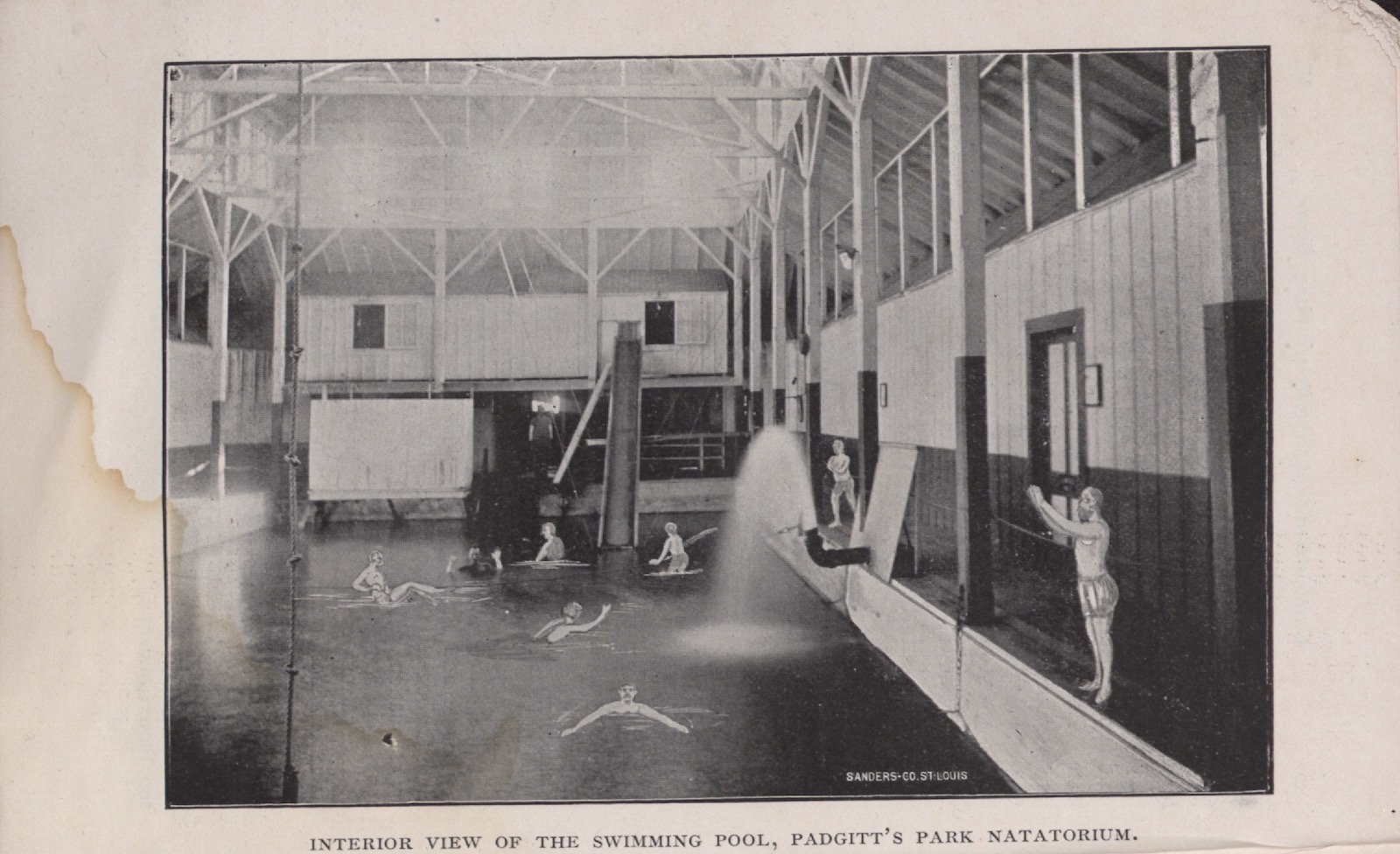

Wells also filled natatoriums, where white Wacoans perceived the movement of water and people as curative. Padgett’s Park Natatorium featured twenty-four bathrooms with porcelain tubs, a dozen vapor baths, two needle baths, electric and Russian baths, and a sweating and cooling room. The Natatorio-Sanatorium, Padgett’s rival, was a seven-floored palace boasting the same plus cold plunges and needle baths that ostensibly healed through pressurized jets. In pools, swimmers did laps, went down slides, and used gymnastic equipment like hanging rings and ropes. Because the pressure and speed of water alternated—and Wacoans exercised in it—the city became a healing center of the world. By one estimate, “hundreds of invalids, nay thousands, have flocked thither, got relief of their aliments, [and] hung up their crutches for monuments.” Attributing its alleged “lowest death rate in Texas” to “God’s gifts to Waco,” promoters challenged its white patrons to leave unhealed.21

As white Wacoans marveled at the kinetic properties of wells, they mapped them onto their social geography as well. Isaac Goldstein founded the society paper Gossip in November 1892. Months later, he rechristened it Artesia to promote Waco’s wells. The name reflected his “hopes to be as clear in its delineation of facts as the pool of Bethesda, and as replete with healing for those afflicted with ennui.” As with wells, the paper measured, monitored, and celebrated the movement of people. This four-page weekly dedicated itself to covering the fashion, parties, gossip, and activities of Wacoans. At least the final half page always tracked people’s movements to and from the city. Where they went and for how long was a constant subject of public comment and concern. For this very reason, local provocateur and publisher William Cowper Brann suggested “Meddlerville” would be a better name for the city. Brann elaborated, “Of our 30,000 inhabitants fully one-third have an idea that heaven is an eternity of keyholes and that angels have more eyes than Argos.”22

Frenetic energy poured from the earth into the streets. Ever since the Bicycle Club formed in 1892 and convinced businessman Tom Padgett to build a racetrack, bicycling seemed an unstoppable mania. The “bicyclius” had become a “pandemic,” Brann observed. “The landscape is literally alive with whirling wheels and churning legs—legs of all kinds, colors, classes and conditions.” Wacoans aestheticized movement, turning it into an opportunity for social spectacle. “It was a beautiful sight from the stand to witness the wheelmen, gaily attired, spinning around the track on their glittering wheels,” Artesia reported. By 1885, bike races pairing bicyclists against each other, roller-skaters, and horses became a popular feature of social life. Marveling at their relative speeds, these races became “a social affair of importance” marked with elaborate parades that rivaled the Columbian Exposition.23

When white women took up bicycling, public reaction underscored that unfettered movement was a right of white men only. Debate over the perils of women-on-wheels was not unique to Waco, but it turned on a different axis. All outrage over women cycling came down to fear over the independence the bicycle offered them. Nevertheless, the form that discourse took varied. Beyond Waco, Americans framed the debate in terms of the physical and moral damage the bicycle would cause. Wacoans, on the other hand, were clear that their protest had little to do with sex or injury and everything to do with how women moved in the presence of men. Waco News observed that the bicycle had a woman “working her limbs like a convict in a treadmill.” They should be horseback riding instead. The latter was “graceful,” the former, “ridiculous.”24

William Cowper Brann honed this view. Unlike those claiming bicycles created infertile prostitutes, he dismissed the bike as sheer fad unrelated to morality. It was offensive because it made women move in all the wrong ways: “The wheel is the enemy of female beauty, and beauty is my religion.” They went too fast, disrupting their natural harmony by becoming “a blot on the landscape.” All men really wanted was “to forget that lovely woman has legs, to resume our adoration of the mysterious.” Walking made woman “a perfect symphony” demonstrating “the poetry of motion” rather than “an ungraceful trunk equipped with sprawling legs that awkwardly churn the atmosphere.” (White) women were too good, too pure, and too harmonious for violent speed.25

Form aside, movement in and of itself remained a sacred right for white men and women alike. Its significance is revealed in the inverse: the restriction of movement for social outcasts. By authority of its new charter, Waco legalized prostitution in 1871. From the start, the sin was not one of commission but of visibility. Residents immediately lobbied politicians to “banish the women from the sidewalks in daylight” and perhaps across the Brazos River. In 1889, Mayor Champe McCulloch crafted a two-part solution that would at once eliminate prostitutes’ visibility to the public and increase it to the state. First, Waco rezoned buildings between Jefferson Avenue, Washington Avenue, Two Street, and the Brazos River to contain legalized prostitution. Second, quarterly city licenses and bimonthly county medical exams formed a register of prostitutes to surveil them. What seemed like generic Progressive Era containment and regulation took on a particularly cruel hue in a place that perceived movement as a life-affirming privilege, and confinement as death.26

Carceral rhetoric underscored the point. Wacoans named this legal zone the “Reservation.” Racial overtones aside, it implied women could not leave, a message that newspapers reaffirmed in references to prostitutes as “inmate[s] of the Reservation.” It was a designation given to anyone living within its bounds until proven otherwise, as in one 1892 police court case that legally established a pianist and housekeeper as “residents” rather than inmates after finding no proof of sex work. Inmates who ventured outside the Reservation became “vagrants”—”a polite name for prostitution,” according to Waco Evening News. If they wanted to buy provisions in town, they had to hire messengers or a city hack to take them to stores after hours. Some storeowners barred prostitutes from entering and instead sold wares through a curtain in the hack. For men, the Reservation was a permeable boundary; for women, to enter the Reservation was to pass through the veil, never to return.27

Migration, wells, bicycles, prostitution—these were just a few of the everyday kinetic spectacles white Wacoans imagined, scrutinized, and framed in terms of motion. This was the world Wacoans had built around movement, and in 1896, the Crash at Crush escalated their obsession.

The Crash at Crush

The Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad (also known as “the Katy”) had a storied career in Texas as the first railway connecting the state to the North in 1872. A decade later, it reached Waco, joining four other lines. When agent William Crush pitched the idea for the Crash at Crush, his motive was obvious: drum up business by selling excursion fares for the spectacle.28

Less clear was his inspiration. Perhaps Crush heard about traveling salesman Alfred Streeter’s staged collisions months prior in the Midwest. Streeter used the spectacle to act out the great political battles of the day, labeling opposing engines with “McKinley” and “Bryan” or “Gold Standard” and “Free Silver.” Perhaps Crush drew inspiration from crowds flocking to a train accident he witnessed. Or, perhaps it was an attempted morality play. There was no clearer symbol of the junction of modernity, speed, and the New South than railroads. With 90 percent of southern counties containing a railroad by 1890, they were the consummate tangible symbol of laissez fare capitalism. They were also the most dangerous, embodying risk on fiscal and personal levels. A controlled wreck could paradoxically reassure passengers fearful for their safety.29

Whatever Crush’s inspiration, the stunt took on its own meaning within the broader context of Waco. Waco both qualified and heightened historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s finding that the train created a vision of the world in motion. Wacoans shared this vision, but it originated in the prior thirty years of city growth. The train was merely symptomatic, Crush its logical conclusion.30

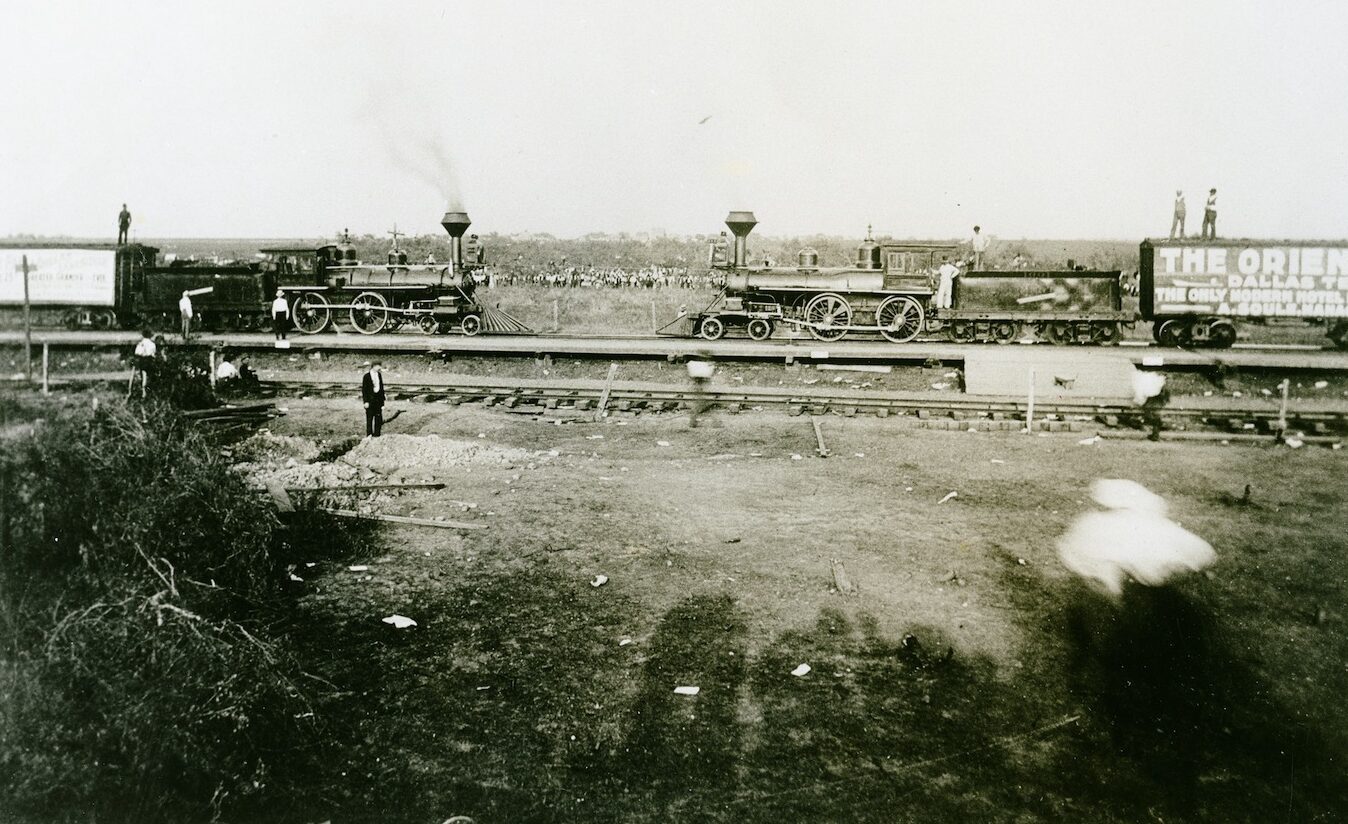

Once the Katy approved Crush’s scheme, Crush and Waco’s local agent scouted a site over two days in August 1896. Fourteen miles north of Waco, the spot chose them. A “natural amphitheater” would allow the trains to run north to south while spectators watched atop a plateau to the west. A 2 percent grade would funnel the trains into each other.31

Waco buzzed with anticipation. The sheer kinetics of the spectacle captured imaginations. In the streets, “Most people quit talking politics a few days ago and took up the subject of head-end collisions.” In anticipation, Wacoans acted out the collision with their bodies. The Houston Post reported, “Not infrequently could be seen an earnest looking citizen plodding along the sidewalk muttering in an undertone, and presently he would jab his right fist into the palm of his left hand and you would know that he had witnessed a collision—in his mind.”32

Even before the crash, journalists fixated on speed. The Dallas Morning News had joined Katy officials for test runs to locate the precise point of collision. “She moved off very slowly, but in two seconds was rushing along,” the journalist marveled, “and in half a minute was going like the wind, and all the boys had to hold on hard to keep from being shaken off.” The following day, the Katy ran another test “for the entertainment of the crowd,” members of which could “see for themselves just how these engines can run.” These were early indications that Crush was less about a spectacle of ruin than one of movement.33

The unfolding event was sublime. When attendees described it, they focused less on death and destruction than on the kinetics of it all: of resources, trains, and people. On September 15, 1896, thousands of Texans hopped on trains, seduced by the promise of movement on display on an unseen scale. At 3:00 p.m., the two trains arrived to raucous cheers. The Katy had them renumbered and repainted in bright green, yellow, blue, and “vermillion to add life to the effect.” They were painted “gaudy and gay” to streak against nature as they careened towards each other. At 5:00 p.m., the collision began with the trains “shaking hands” before reversing to their starting points. Ten minutes later, their crews counted sixteen puffs, tied down the whistles, and jumped to safety. The movement was awesome, powerful, and intoxicating. Papers recreated the rush of the crash—detailed it, drew it out, suspended it forever in motion. “They rolled down a frightful rate of speed to within a quarter of a mile of each other. . . . Now they were within ten feet of each other.” Then: the crash.34

Contrary to one prediction, there was no detailed “autopsy” on the wreck, nor any talk of it being “more ghastly than that of scattered lights, livers, brains, and viscera on the ten-story buildings of Chicago.” Instead, spectators gawked at the kinetics involved. “Imagine,” the Houston Post beckoned, “a force of 175 tons, or 350,000 pounds, going at the rate of ninety miles an hour, striking an immovable body. The result can never be described. Words bend and break in the attempt to record on paper the pictures on the mind, or the impression of the eye.” Still, the press tried its best to capture the speed for readers. Dallas Morning News reported, “A crash, a sound of timbers rent and torn, and then a shower of splinters. . . . Both boilers exploded simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half of a driving wheel, falling indiscriminately on the just and unjust.”35

The crowd was “awe-stricken.” As debris showered over them, journalists tracked their trajectories. Smokestacks and pieces of boilers “sailed” a quarter mile. Two one-ton trucks flew one hundred feet high, bulldozing a telegraph post. A driving wheel “sizzled and screamed, cutting its way through space with the speed of a shell.” Brake chains twisted “like a serpent.” Then, “The heavens had opened and emitted millions of undistinguishable pieces of iron and steel. . . . They had the speed of a bullet, and being larger in size were more destructive.” The trains’ energy seemed to transfer to the crowd. Belting a “united yell,” attendees ripped apart wooden fences to charge the wreck and seize souvenirs. One reporter concluded, “The crowd seemed to be indifferent as to the catastrophe.”36

Crush became a turning point in Waco’s perceptions of motion. For some, movement—once redemptive—was now uncontrollable and traumatic. As simulacra, it was fine, but now, the Katy’s chief clerk claimed, “It was too realistic to be comfortable.” It left some unable to hear or look at trains without recoiling. Three decades of celebrating movement and increasing speed led to this—and some did not like what they saw.37

For most, though, Crush was a bona fide triumph. Death and mutilation paled in comparison to the excitement of bodies in motion. One paper called it “a howling success.” After all, “The trains performed perfectly.” Another wrote that despite “its sad feature . . . the collision was superb, awe-inspiring in the extreme and grand in sublimity.” Afterward, one attendee penned an illuminating letter to the Austin Daily Statesman explaining how Crush could be a success not in spite of tragedy but because of it:

Why, I would shut up the Iliad, and let Hector and Achilles and all the gods and goddesses of the beautiful Grecian Mythology fight it out, while I watched those Iron Titans rushing and roaring along the plain to meet in one grand concussion, where sight and sound, form and motion, merged and was lost in one grand uproar, and from out of the cloud of smoke and steam rained down a shower of iron and wooden missiles.

He had come to see “pure material bodies” in motion and Crush more than delivered. This was a process to marvel at, not a travesty to scrutinize.38

In this respect, Crush was clarifying. From then on, Wacoans doubled down on celebrating movement for movement’s sake. Artists glorified the event as the supreme kinetic spectacle. Jervis Deane—”leading photographer of Waco”—won photography rights from the Katy. Afterward, he and his brothers published at least six large photos of the collision. The first two depicted Crush beforehand. The third, The Trains Just as They Struck, captured the two locomotives as blurry streaks immediately before colliding. It was a breathtaking image, not for its ability to freeze a moment but rather for its suspension of the trains in perpetual motion. The trains’ advertisements were blurry, the engines appeared to melt, and the smoke trails look as if thickened and smeared with a brush. The juxtaposition of the crisp stillness of the foreground heightened the effect. Finally, The Explosion. Again, the photo drew attention to the left, where an amorphous burst of energy erupted, set against the tranquility of an undamaged end of one of the trains. The point was not to capture a pristine moment but an infinitely unfolding explosion, shrapnel flying to all parts of the frame. Like the articles describing the event, Before the Crowd Got to the Wreck focuses not on the ruins situated in the far left of the photo but rather the blurry masses sprinting toward the trains for souvenirs. Separately, these photos underscored the speed of each individual act of the event; together, they provided a zoetrope of motion—an animated loop in the viewer’s mind of the movements surrounding the crash. It was a work of art that captured and celebrated the kinetics of it all.39

Crush entered other media in similar ways. Early in his career, Black pianist Scott Joplin was on tour with his Texas Medley Quartette in 1896 when he found a publisher in Temple, thirty miles south of Waco. One month after Crush, Joplin published his third piece of music that broke the mold: Great Crush Collision March, a sonic reenactment of the crash “dedicated to M. K. & T. Ry.” The march began daintily, conjuring images of merriment in Crush before the stunt. Launching into the march’s “trio,” the song defied the march form. After a series of foreboding chords, Joplin entered a run of bass notes accompanied by low octave treble chords played fortissimo. “The noise of the trains while running the rate of sixty miles per hour,” he annotated. Then, discords in a high octave, played with syncopating grace notes. “Whistling for the crossing,” he noted. Another bass run: “Noise of the trains.” More syncopated discords but with fewer beats and more urgency. “Whistle before the collision.” Hands careening up and down the black and white trestles of the keyboard, they finally crash on a chord at the lowest end of the register. “The collision,” Joplin noted, played fortissimo with the pedal and suspended with a fermata, instructing musicians to hold the chord as long as desired for dramatic effect. Joplin then returned to the gentler open of the march. Scholars have criticized the piece for ending anticlimactically, but what they deemed a failure may actually be Joplin’s profound understanding of how white Wacoans responded to violent movement: by a quick return to normalcy. Because it utilized syncopation—a kind of melodic violence—for the first time, musicologist Rudi Blesh raised the possibility that this song was the origin of ragtime itself. Perhaps an understanding of kinetics and violence in the white South armed Joplin with a new way of conceptualizing music.40

Both Deane’s and Joplin’s works were stunning multisensory celebrations of violent speed. Other artists, like photographer Fred Gildersleeve—Deane’s heir apparent—followed suit, pioneering aerial photography and documenting speed, machinery, and motion around Waco into World War I. Over a decade before a car crash inspired Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Martinelli to draft a futurist vision of a fast, destructive modernity, white Wacoans became futurists themselves. It was a vision inspired by war, reified through banalities of urban life, codified in its exclusion of and violence toward women and people of color, and exaggerated in Crush.

The following week did not slow down. Artesia reflected on a series of bike races, dances, a circus, a fashion bazaar, a Young Men’s Christian Association party, and “a succession of lesser contrasts to make up a week of as truly Bohemian living as one could demand.” Then there were the normal kinetic spectacles: “An afternoon canter, a spin on the bike, a turn on the drives, or a swim in the pool—they have all come within the past week as adjuncts to the more potent allurements for enjoyment.” The columnist maligned the circus’s quality, but that was hardly the point. “One goes for the frolic, not the performance.”41

After Crush, Brann ridiculed J. B. Cranfill, one of his regular enemies and editor of the Baptist Standard, who criticized the collision. “In his mind’s eye he sees buildings burned; whole hecatombs of bleating animals roasted, a man fricasseed alive at fifty cents admission, the Katy running excursion trains to all these horrors and filling its coffers with cash by wrecking the car of progress, telescoping civilization.” Cranfill may have been onto something. Perhaps he sensed the dreadful ends that sacralized anarchic motion could—and would—bring, climaxing with the 1916 spectacle lynching of Jesse Washington, which Gildersleeve photographed in piecemeal blurry fashion as a perpetually unfolding process of destruction rather than the typical postmortem record.42

The New South pulsed with movement, and Waco was no exception. Other cities also created expositions, rode bicycles, and advertised their natural resources to invite immigration after the Civil War. Yet, casting out to the margins of the New South, free of the interference generated by war and boosterism, Waco makes clear what places like Atlanta obscure: this was not regeneration, it was an unleashing of kinetic energy, regardless of the form it took. The Civil War profoundly reoriented white southerners’ perceptions of the material world. They became lay cultural theorists in myriad ways, one of which was embedding speed and mobility within everyday life. Progress suffered an endless array of mobile metaphors, but in the wake of the Civil War’s destruction and dislocations, it was literal. A marvel, a tragedy.

This essay first appeared in the Built/Unbuilt Issue (vol. 27, no. 2: Summer 2021).

ALEX HOFMANN is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Chicago, completing his dissertation, “Southern Sublime: Legacies of Civil War Violence in the New South.” In the fall, he will be a teaching fellow in the Division of the Social Sciences and the College at the University of Chicago.NOTES

1. Austin C. Rogers, “A Pre-Arranged Head End Collision,” in The Cosmopolitan: A Monthly Illustrated Magazine November 1896–April 1897, vol. 22 (Irvington, NY: Cosmopolitan Press, 1897), 125, 129; “They Are All Ready,” Dallas Morning News, September 14, 1896; “Railroad Matters,” Dallas Morning News, September 13, 1896; “Stand at Crush Station,” Democrat (McKinney, TX), September 10, 1896; “Scene of the Collision,” Dallas Morning News, September 16, 1896; “Taking Care of the Crowds,” Dallas Morning News, September 16, 1896; “Railroad Matters. The Katy’s Grand Scientific Show of a Collision Between Two Trains,” Dallas Morning News, August 13, 1896; “Railroad Matters,” Dallas Morning News, September 12, 1896; “Dallas Well Represented,” Dallas Morning News, September 16, 1896; “Is Over at Last,” Dallas Morning News, September 16, 1896; John Banta, “Railroad Publicity Stunt Ended in Tragic Explosion,” January 23, 1983, box 9, folder 5, Thomas E. Turner Sr. Papers, accession #2200, Texas Collection, Baylor University (hereafter cited as Texas Collection).

2. “They Are All Ready”; Letter, Maggie Dunn to W. H. Clift, September 16, 1896, box 246, folder 20, Crush Collision Collection, accession #1253, Texas Collection. Crush remains remarkably understudied. Extant literature ranges between reading Crush as economic escapism and a physical manifestation of high and low culture wars. See Mike Cox, Train Crash at Crush, Texas: America’s Deadliest Publicity Stunt (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2019), 27; and Nancy Bentley, Frantic Panoramas: American Literature and Mass Culture, 1870–1920 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 1–4. Despite varying interpretations, all project modern astonishment onto the Crush collision and treat it as an anomalous event. By “kinetic spectacular,” I mean events that captured the attention of masses and traded on movement.

3. Paul M. Gaston, The New South Creed: A Study in Southern Mythmaking (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 7, 54, 92–93, 121–132, 162–163. Regarding pellagra, see Jack Temple Kirby, Mockingbird Song: Ecological Landscapes of the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 203–210. For hookworm, see John Ettling, The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981). On poverty and the wealth gap in the New South, see Gaston, New South Creed, 45–47; and Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 22. For how the South got its public image as backward and antimodern, see Scott L. Matthews, Capturing the South: Imagining America’s Most Documented Region(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); and Natalie J. Ring, The Problem South: Region, Empire, and the New Liberal State, 1880–1930 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012).

4. C. Vann Woodward, The Origins of the New South, 1877–1913 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993), 140–141; James C. Cobb, Redefining Southern Culture: Mind & Identity in the Modern South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999), 2. Prominent texts on the late economic development of the South include Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986); and Bruce J. Schulman, From Cotton Belt to Sunbelt: Federal Policy, Economic Development, and the Transformation of the South, 1938–1980 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991). On southern modernity, see Benjamin S. Child, The Whole Machinery: The Rural Modern in Cultures of the U.S. South, 1890–1946 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019); Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (New York: First Vintage Books, 1999); and Charles Postel, The Populist Vision(New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

5. Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (New York: Penguin Books, 1988), 288; Jackson Lears, Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877–1920 (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 1–9; William A. Link, Atlanta, Cradle of the New South: Race and Remembering in the Civil War’s Aftermath(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 33–34, 55–58; Woodward, Origins of the New South, ix. On the influence of technology on perceptions, see Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (Oakland: University of California Press, 2014). On speed, power, and the modern state, see Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics: An Essay on Dromology, trans. Mark Polizzotti (New York: Semiotex(e), 1986). On the impact of speed on American and European aesthetics, see Hillel Schwartz, “Torque: The New Kinaesthetic of the 20th Century,” in Incorporations, ed. Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter (New York: Zone Books, 1992). For examinations of the texture of everyday life in the New South, see Ayers, Promise of the New South, vii–ix. On the relation between Civil War destruction and New South development, see Link, Atlanta, 3.

6. Waco occupied a unique regional position as both South and West. Given its historical ancestry, wartime experience, segregation, and cotton culture ranging from plantation to sharecropping, Waco was predominantly southern until at least the 1920s, when the demographics and scale of agriculture shifted toward a western model of ranches and Mexican labor. See Neil Foley, The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 2–5.

7. In 1860, McLennan County contained 6,206 white and enslaved people. While deaths and later enlistments make the actual number unknowable, the most reliable estimate was that 1,200 white men were of eligible age for service (16–45) and that 1,300 served. Harold B. Simpson, Gaines’ Mill to Appomattox: Waco & McLennan County in Hood’s Texas Brigade (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1963), 30. Waco’s disinterest in Confederate memorialization is all the more shocking considering Texas had the highest per capita and whole numbers of surviving Confederate veterans in 1890. Of the 432,020 Confederate veterans living in the United States, 66,791 lived in Texas. These comprised 2.99 percent of the state’s population. Virginia—the crucible of Confederate memory—was its closest rival, with veterans comprising 2.94 percent of the population. Eleventh Census of the United States, 1890, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1897), 804–806. While there is a Confederate monument in Waco’s Oakwood Cemetery, this structure served a different purpose than the Confederate monuments placed in central public spaces. See Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 66–67. After its founding in 1887, Waco’s Pat Cleburne Camp of the United Confederate Veterans rarely drew more than 150 members. Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of Waco, 1888–89(Galveston, TX: Morrison & Fourmy, 1889), 47. The UDC had only twenty-five members when organized in 1894. Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of Waco, 1894–95 (Galveston, TX: Morrison & Fourmy, 1895), 59.

8. Letter, R. N. Goode to Mary Virginia Thompson, March 19, 1865, box 1, folder 3, Goode-Thompson Family Papers, 1837–1993, accession #2794, series II: Richard N. Goode, Texas Collection; Letter, Patience Crain Black to James Black, June 17, 1862, in A Copy of the Letters of Patience and James Black (1862–1865): Their Correspondence while Separated by the Civil War (1972), 39.

9. Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution: 1863–1877 (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), 125, 119, 204, 352–354; Roger L. Ransom and Richard Sutch, One Kind of Freedom: The Economic Consequences of Emancipation, 2nd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 41–42, 171; Foley, White Scourge, 28; Charles William Ramsdell, “Reconstruction in Texas,” in History of Texas Democracy: A Centennial History of Politics and Personalities of the Democratic Party, 1836–1936, ed. Frank Carter Adams (Austin, TX: Democratic Historical Association), 1: 237; Patrick G. Williams, Beyond Redemption: Texas Democrats after Reconstruction (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2007), 15–16, 55–60; Carl H. Moneyhon, Texas after the Civil War: The Struggle of Reconstruction (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004), 3. Economists Ransom and Sutch argued that the region’s straggling economy resulted from the loss of enslaved labor, not physical destruction. Ransom and Sutch, One Kind of Freedom, 50. Whether or not the Civil War’s desolation was to blame was irrelevant, for white southerners felt it was. It was this perception that triggered a massive demographic shift.

10. John Sleeper and J. C. Hutchins, Waco and McLennan County, Texas (Waco, TX: Examined Steam Job Establishment, 1876), 26; A Memorial and Biographical History of McLennan, Falls, Bell, and Coryell Counties, Texas (Chicago: 1893), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, 47–48, 121; “Reconstruction in McLennan County,” in The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas, ed. Dayton Kelly (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1972), 221. For representative individual examples of Confederate veterans in Texas’s postwar economy, see “Forsgard, Samuel J.,” “Johnson, Charles L.,” and “Makeig, Stephen L.,” in The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas, ed. Dayton Kelly (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1972), 104, 143, 178; and Memorial and Biographical History, 543, 725–726.

11. Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York: Vintage Books, 1980), 30–33; Eleventh Census, 400; Ralph A. Wooster, Civil War Texas: A History and a Guide (Austin, TX: Texas State Historical Association, 1999), 32, 45. Only Arkansas and Florida topped 100 percent growth between 1860 and 1890. Williams, Beyond Redemption, 4. After Texas, the ex-Confederate state with the most residents born out of state was Arkansas with 355,498 people. Tenth Census of the United States, 1880, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1883), 480. Texas was the most popular destination for emigrants from Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas; the second most popular for Tennessee, Missouri, and Georgia; and the third most for North Carolina and Florida. Tenth Census, 480–483.

12. In 1870, most migrants to McLennan County had come from Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Georgia, and Louisiana. Ninth Census of the United States, 1870, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1872), 372. By 1880, more expansive data added Arkansas, Missouri, Kentucky, and Virginia to this list. Tenth Census, 530. Mrs. J. B. Powell, interview by Edward Townsend, July 7, 1938, box 4J132, folder 2, Works Progress Administration Records, 1933–1943, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin (hereafter cited as WP Records). For representative individual examples of white southerners relocating to Waco to become cotton planters, see Sleeper and Hutchins, Waco and McLennan County, 114–116; and “Brown, Henry W.” and “Gerald, George Bruce,” in The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas, ed. Dayton Kelly (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1972), 38, 110. Similarly, Patrick G. Williams argued that although the “planter thesis” held for Texas, where antebellum and secessionist leaders regained political power after the war, this was not a simple continuity because they had to contend with different interests as a result of demographic shifts. Williams, Beyond Redemption, 5–9.

13. “Chisolm Trail,” in The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas, ed. Dayton Kelly (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1972), 104; Memorial and Biographical History, 57; W. R. Poage, McLennan County before 1980 (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1981), 59; Sleeper and Hutchins, Waco and McLennan County, 62; C. D. Morrison, General Directory of the City of Waco, for 1878–79 (Waco, TX: Examiner, 1877), 8; “Telegraph—Waco a Cotton Market,” Semi-Weekly Register, September 29, 1869, box 4J132, folder 1, WP Records.

14. J. W. Riggins, “Big Thing for Texas,” Waco Evening News, October 10, 1893; promotional pamphlet, “The Texas Cotton Palace,” 1894, box 2, folder 8, Texas Cotton Palace Records, accession #792, Texas Collection; J. W. Riggins, “Texas State Cotton Palace,” Waco Evening News, October 14, 1893.

15. Charles Cutter, Cutter’s Guide to the City of Waco, Texas (Waco, TX: 1894), 53.

16. Cutter, Cutter’s Guide, 55; “Texas Cotton Palace,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 9, 1894; “Social and Current Events,” Artesia, November 11, 1894; “Where Cotton Reigns,” Marion Daily Star, December 5, 1894; promotional pamphlet, 1894; “Cowboy Day at Waco,” Galveston Daily News, December 1, 1894; “The Cotton Palace,” Galveston Daily News, November 12, 1894.

17. “Negro Day,” Austin Daily Statesman, November 25, 1894; R. Scott Huffard Jr., Engines of Redemption: Railroads and the Reconstruction of Capitalism in the New South(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 101–102; Jane Dailey, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, and Bryant Simon, “Introduction,” in Jumpin’ Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights, ed. Jane Dailey, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, and Bryant Simon (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 4; Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor, Colored Travelers: Mobility and the Fight for Citizenship before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 1–2, 92.

18. “St. Louis Day,” Galveston Daily News, November 18, 1894; James Morton, “The Cotton Palace,” Daily Tobacco Leaf-Chronicle, December 1, 1894.

19. Cutter, Cutter’s Guide, 55; “Pertinent Paragraphs from the Palace,” Artesia, November 25, 1894; Morton, “Cotton Palace.”

20. “Artesian Wells” in The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas, ed. Dayton Kelly (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1972), 10–11; Cutter, Cutter’s Guide, 7; Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of Waco, 1892–93 (Galveston, TX: Morrison & Fourmy, 1893), 3–4.

21. Cutter, Cutter’s Guide, 11–15; Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of Waco, 1894–95, 4.

22. “Artesia, The,” in The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas, ed. Dayton Kelly (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1972), 25–26; Cutter, Cutter’s Guide, 10; “Artesia,” Artesia, February 19, 1893; William C. Brann, “The Iconoclast Told to Leave Town,” in The Complete Works of Brann: The Iconoclast (New York: Brann, 1919), 9:204.

23. Brann, “Editorial Etchings,” in Complete Works of Brann, 7:79; “Social and Current Events,” Artesia, August 23, 1896; “At the Rink Last Night,” Waco Daily Examiner, February 28, 1885; “Prince Won the Race,” Waco Evening News, June 15, 1893; “The Week in Society,” Waco Evening News, October 28, 1893.

24. Sarah Hallenbeck, Claiming the Bicycle: Women, Rhetoric, and Technology in Nineteenth-Century America (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016), 31–32, 132–134; Richard Harmond, “Progress and Flight: An Interpretation of the American Cycle Craze of the 1890s,” Journal of Social History 5, no. 2 (Winter 1971/1972): 244; “Tea Table Gossip,” Waco Evening News, May 16, 1893.

25. Brann, “The Bike Bacillus,” in Complete Works of Brann, 1:253–256; Brann, “Salmagundi,” in Complete Works of Brann, 11:42; Brann, “Editorial Etchings,” Complete Works of Brann, 7:80–81; Brann, “Salmagundi,” in Complete Works of Brann, 5:48.

26. Davis v. The State, in Central Law Journal 5 (1877): 288; “Untitled,” Waco Daily Examiner, October 31, 1875, box 4J134, folder 1, WP Records; “Untitled,” Waco Daily Examiner, January 21, 1876, box 4J135, folder 1, WP Records; Margaret H. Davis, “Harlots and Hymnals: A Historic Confrontation of Vice and Virtue in Waco,” Mid-South Folklore 4, no. 3 (January 1976): 88; J. T. Upchurch, Traps for Girls and Those Who Set Them: An Address to Men Only (Arlington: Purity, 1908), 11, 23; Orville Wilkes, Diary, September 30, 1933, Waco, Texas: The Reservation (Vertical File), Texas Collection. The conventional view treats vice as an abstraction rather than deeply embedded in place. See Davis, “Harlots and Hymnals,” 92; and Amy S. Balderach, “A Different Kind of Reservation: Waco’s Red-Light District Revisited, 1880–1920” (master’s thesis, Baylor University, 2005), 4, 35.

27. “Mayor’s Court,” Waco Evening News, May 21, 1892; “An Interesting Decision: In the Police Court Relating to Female Residents of the Reservation,” Waco Evening News, January 12, 1892; “Police Court,” Waco Evening News, March 7, 1889. Because social codes conducting prostitutes’ behavior were informal, sources are limited to Wacoans recalling the Reservation decades later. See William H. Curry, A History of Early Waco (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1968), 129–130; Davis, “Harlots and Hymnals,” 90; and Bob Darden, “Best Legal Whorehouse in Texas,” Dallas Times Herald Westward, March 27, 1984, Waco, Texas: Prostitution Clippings (Vertical File), Texas Collection.

28. Missouri, Kansas, & Texas Railway Company, The Opening of the Great Southwest 1870–1945: A Brief History of the Origin and Development of the Missouri Kansas and Texas Rail Way (M. K. T. Lines, 1945), 2, 6–7; V. V. Masterson, The Katy Railroad and the Last Frontier (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1952), 223; Morrison & Fourmy’s General Directory of the City of Waco, 1896–97 (Galveston, TX: Morrison & Fourmy, 1897), 63–66.

29. Cox, Train Crash at Crush, 39–48; Frank Barnes, “Train Wreck,” True West, box 9, folder 5, Thomas E. Turner, Sr. Papers, accession #2200, Texas Collection; Huffard, Engines of Redemption, 2, 234–236, 138–139; Scott Reynolds Nelson, Iron Confederacies: Southern Railways, Klan Violence, and Reconstruction (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 6–8; Schivelbusch, Railway Journey, 129–131. On railroads and modernity, see Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

30. Schivelbusch, Railway Journey, 60–64.

31. “Head-End Collision,” Dallas Morning News, August 5, 1896; “The Katy’s Grand Scientific Show of a Collision”; “Scene of the Collision.”

32. “The Collision at Crush,” Houston Post, September 16, 1896.

33. “They Are All Ready.”

34. “Railroad Matters,” Dallas Morning News, September 11, 1896; “Railroad Matters,” Dallas Morning News, September 6, 1896; “Is Over at Last”; “Railroad Matters,” Dallas Morning News, September 12, 1896; Barnes, “Train Wreck,” WP Records, 16.

35. “Home Notes and Personals,” Dallas Morning News, August 14, 1896; “The Crush Collision,” Houston Post, September 17, 1896; “Is Over at Last.”

36. “The Katy Collision Was Entirely Too Realistic—Nine People Were Injured by It,” Austin Daily Statesman, September 16, 1896; “Collision at Crush”; “Is Over at Last”; “Mrs. Deane on the Crush Collision,” Dallas Morning News, October 1, 1896.

37. “Stories of Some Witnesses,” Dallas Morning News, September 17, 1896; Letter, Maggie Dunn to W. H. Clift, September 20, 1896, box 246, folder 20, Crush Collision Collection, accession #1253, Texas Collection.

38. “May Be Another Victim,” Dallas Morning News, September 17, 1896; “Collision at Crush”; “Katy Collision Was Entirely Too Realistic”; George W. Walling, “Accurate Estimates,” Austin Daily Statesman, September 20, 1896.

39. “Railroad Matters,” Dallas Morning News, August 16, 1896; “Deane, Jervis C.,” in The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas, ed. Dayton Kelly (Waco, TX: Texian Press, 1972), 84; Memorial and Biographical History, 553.

40. Edward A. Berlin, King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 28; Rudi Blesh, “Scott Joplin: Black-American Classicist,” in The Complete Works of Scott Joplin, ed. Vera Brodsky Lawrence (New York: New York Public Library, 1981), 1:xiii–xviii. For criticism of the ending of Great Crush Collision March, see Berlin, King of Ragtime.

41. “Social and Current Events,” Artesia, October 4, 1896.

42. Brann, “Salmagundi,” in Complete Works of Brann, 6:238–239. The ways in which local photographer Fred Gildersleeve portrayed the lynching of Jesse Washington in progress suggests that it too should be understood as a thoroughly modern form of violence marked by the same fascination with speed. Lynching, which white southerners constantly defended as a form of “swift justice,” belongs in this conceptual framework of speed grounded in wartime experiences. This adds to a growing literature on lynching as a quintessential feature of modernity rather than southern backwardness. See Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (New York: Random House, 1998); Jacqueline Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006); and Amy Louise Wood, Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). In this light, it may be no coincidence that spectacle lynchings and train crashes crested at the same time. See Huffard, Engines of Redemption, 138.