On a steamy June afternoon in 1970, a crowd gathered outside the Sea Pines Company’s sprawling headquarters on the southern end of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. Led by the Rev. I. DeQuincey Newman of the South Carolina NAACP, fifty African American protestors came to deliver a message to Charles Fraser, the head of Sea Pines, then the island’s largest, most opulent “plantation” or gated residential community. Brandishing signs with messages like “Fraser Loves Poverty” and “The Rich Get Richer,” the picketers denounced the developer for fighting a proposed chemical plant that would be located ten miles west of the island on Victoria Bluff, a spit of state-owned land that jutted out into the Colleton River. After one hapless Sea Pines employee distributed fliers about the company’s efforts, the marchers made a show of lighting the piled pamphlets on fire. “Instead of giving us propaganda,” Newman boomed above the small blaze, “Charlie Fraser ought to set up a buffet out here for us.” Later, another NAACP leader warned that the protestors could make Hilton Head “look like Montgomery, Alabama, before the end of the summer.” Although nothing of that scale materialized, these incredible scenes brought a strange conclusion to a year-long political fight over environmental and economic justice in the South Carolina Lowcountry.1

The uncomfortable intimacy of poverty and privilege, hunger and natural beauty, on Hilton Head led protestors to Fraser’s front door. By the late 1960s, the island located thirty miles north of Savannah and fifty miles south of Charleston counted around three thousand residents. Just twenty years prior, only a few hundred residents lived there, almost all of them part of the Gullah Geechee people, African American communities in the southern Sea Islands whose unique language, traditions, and foodways exhibit both the retention and adaptation of West African culture in North America. With electric service arriving in 1951, followed by the first bridge to the mainland in 1956, two white families—the Hacks and the Frasers—turned from timbering the island’s pine forests to building a real estate empire. By micromanaging its aesthetics, these developers recreated and sold Hilton Head as a coastal wilderness fit with all the trappings of suburbia. Soon, it attracted waves of new, white residents wanting to secure an exclusive retreat away from the strife and pollution of America’s cities.2

Yet, outside the island’s gated subdivisions, poverty stalked the Lowcountry. In early 1969, news reports and high-profile hearings before congress stamped the area surrounding Hilton Head with labels like “rural slum,” “poverty pocket,” and “the hunger capital” of America. An announcement in October 1969 that the West German company Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF) planned to invest over $100 million in a petrochemical plant nearby raised the hopes of many residents, Black and white, for a much-needed influx of industrial jobs. For others, however, these plans threatened to undermine the viability of traditional maritime occupations and tarnish the island’s natural wonders.3

In a brief but fierce political clash between October 1969 and January 1971, Lowcountry communities divided themselves in ways that defy easy categorization. While many Black leaders joined white politicians in supporting the plant to provide jobs and increase the purchasing power of their communities, others, including members of the Black-led Hilton Head Fishing Cooperative, dissented out of concern that industrial pollution would threaten their livelihoods. In the end, a strategic, temporary alliance between the cooperative and white real estate developers helped defeat the project. This partnership rested on shared concerns that the industrial landscape promised by the plant would prove incompatible with the fishing and tourism industries that gave the area its unique appeal to outsiders and locals alike. Although Black Gullah communities in Beaufort County, home to Hilton Head and the town of Beaufort, took different sides on the BASF debate, these temporary divisions reflected differing strategies toward a common goal: preserving their communities amid intensifying land loss and demographic changes.

The political tug-of-war over the BASF plant seemed like a clear victory for a biracial, interclass environmental movement, though it also left much unresolved. Journalists and historians typically frame this clash as one between economics and environmentalism, but the story also shows the dynamic ways that southerners articulated ideas about home and belonging through interactions with the natural world. While the tactical partnership forged between Black Sea Island communities and white developers grew out of a common desire to protect the landscape, this elevation of the natural world elided the ever-widening power differentials between them. Both groups believed they had a right to defend Hilton Head as their home, yet their visions of to whom the land belonged differed sharply.4

In an age of Black land loss and out-migration, African Americans on both sides of the BASF controversy viewed this issue through the prism of place. Some viewed it as a source of economic development to maintain their ties to ancestral homes and communities, while others feared it would erode their vanishing toehold on the Sea Islands. For both factions, the fight meant more than debates over economics and environmentalism. It was part of a much longer struggle to survive and remain on their home ground. Though new industries and demographic change threatened Gullah communities’ survival at this time, their oft-divergent strategies to confront these threats drew on decades of innovation and endurance to resist slavery, hurricanes, oppression, and changing landscapes. By testifying to the twin injustices of underdevelopment and environmental racism, their oppositional efforts shared a common politics—one that aimed to curb the depletion of cultural and natural heritage in the Gullah South.

In early 1968, the efforts of local Black activists and a white doctor named Robert Gatch convinced US Senator Ernest “Fritz” Hollings and his colleagues to take responsibility for a public health crisis in the Lowcountry. Their reports of high rates of parasitic infection and hunger among the area’s mostly Black, low-income population led to high-profile congressional hearings that shone a harsh spotlight on the persistent inequalities of a changing South. Still, Hollings and other white politicians fixated on the economic deficiencies exposed by the campaign. At one point, the senator quipped, “You don’t catch industry with [hook]worms—maybe fish, but not industry.” Speaking the language of industrial boosterism that transcended the Palmetto State’s growing partisan divide, Hollings’s comments indicated how local and state leaders viewed this sordid reality as a problem that could be managed by doubling down on job recruitment efforts.5

The timing of the BASF plant announcement—within nine months of the hunger hearings—allowed white politicians to present a solution to a problem of their own making. In the celebratory rhetoric of moderate Governor Robert McNair, poverty became an abstraction, a talking point in the service of shameless boosterism. In internal memos passed between the governor’s office and the State Development Board (SDB)—South Carolina’s primary industrial recruitment arm—state officials emphasized the need to portray BASF “as a model of enlightened manufacturers” for its willingness to invest in “a poverty pocket that has received national attention.” In other letters, both the state and the company depicted Beaufort County as a collection of “severely distressed” and “poverty-stricken” communities hit hard by “underemployment and the outmigration of [agricultural] workers.”6

For similar reasons, the white power brokers who governed Beaufort County praised BASF’s plans as an economic godsend. Noting that the company’s total investment represented one of the largest industrial projects in state history, the Beaufort Gazette hailed the project’s potential to “eliminate the current nationwide image that Beaufort County is the poverty pocket of America.” By framing widespread poverty as a simple problem of underemployment, local and state officials replaced the disturbing images of parasites, squalid homes, and children’s distended bellies with more abstract discussions about low per capita income and high rates of out-migration.7

Coming on the heels of the antihunger campaign, some Black residents in northern Beaufort County welcomed the plant with cautious optimism. Many recognized that their organizing efforts proved decisive in getting the governor and others to talk about poverty in the first place. As one African American resident offered a blunt assessment of the racist politics at work, before the hunger hearings, “No politician helped the blacks.” Still, they had little reason to trust the people who now wanted to help the poor after denying the severity of the problem months earlier.8

Despite lingering mistrust over decades of repression by the local white power structure, the promise of well-paying jobs at the BASF plant won the support of a sizeable band of Black leaders. Weighing the progress toward economic justice against the threat of environmental harm, Hazel Frazier, a Black activist in Beaufort, noted that her neighbors had experienced pollution their whole lives, since the town located its main landfill near her neighborhood. “Nobody would want the water polluted,” she noted, “but a lot of men need work.” Charles Simmons—who led Beaufort County’s local Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO)—agreed when a reporter asked him about the plant. “I figure you have to give them a chance,” he shrugged, “There’s just no question, we need jobs, and BASF will bring in jobs.” To support the plant, many African American activists like Simmons and Frazier backed the plant through groups such as the Beaufort Progressive League, the Beaufort County Voters League, and the United Citizens for the Poor. Differences in class, occupation, and geography within the Lowcountry’s African American communities, however, created divergent views about whether the BASF plant offered hope through jobs or ruin through pollution.9

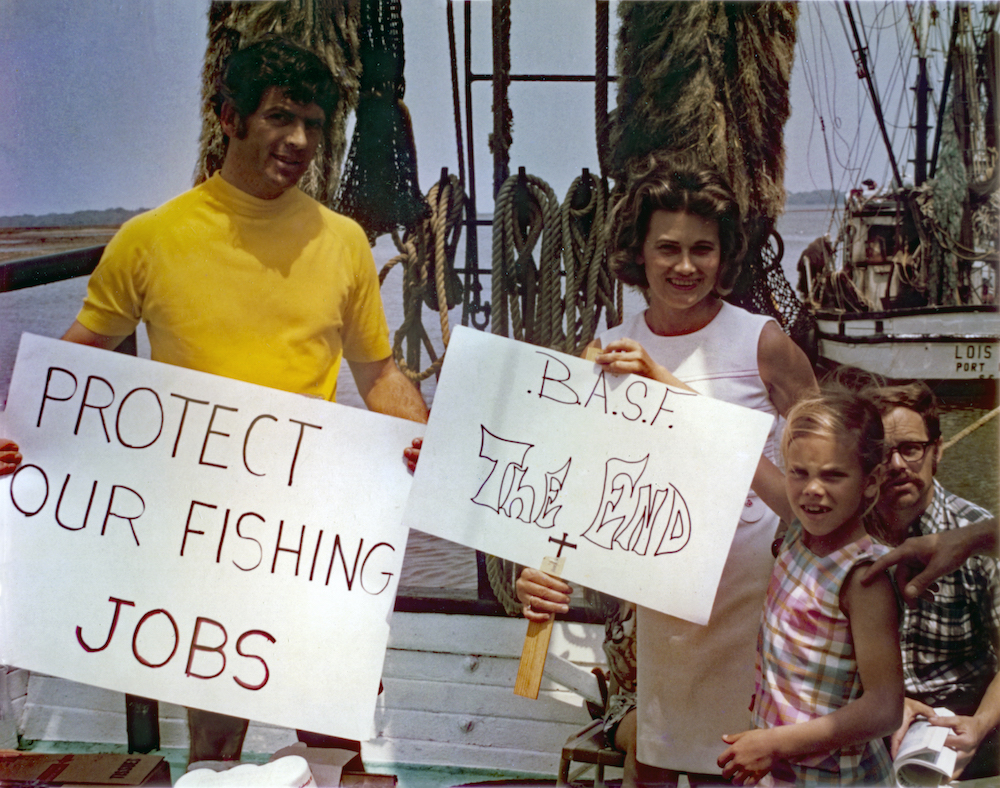

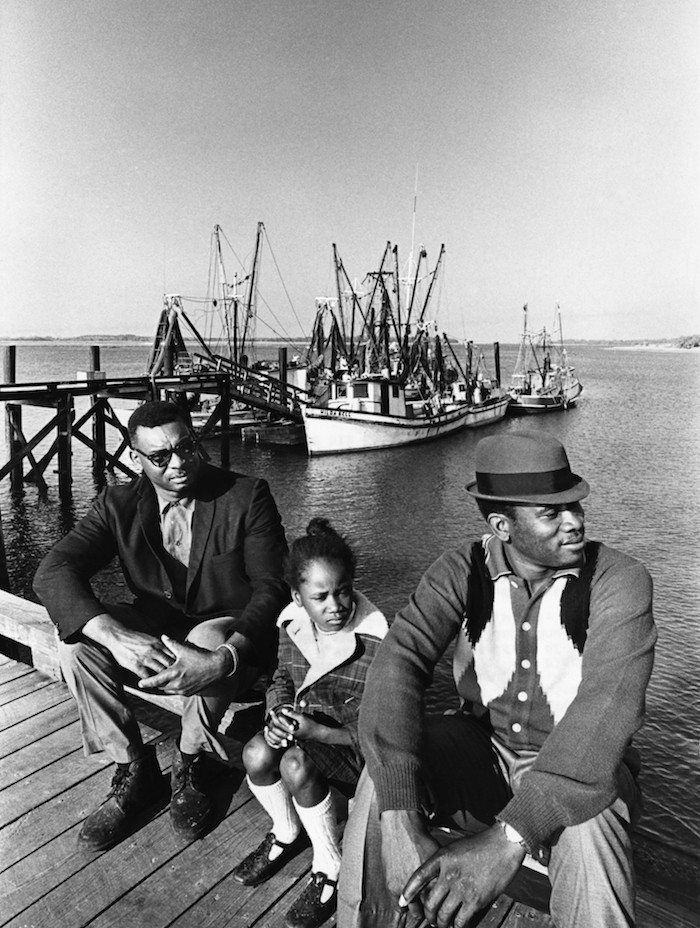

While African Americans living north of the Broad River supported the plant, for the most part, those to the south near Hilton Head largely opposed it. There, the most prominent critiques of BASF came from members of the Black-owned Hilton Head Fishing Cooperative (HHFC). Established in 1966 with a grant from the Farmers Home Administration, the HHFC grew into a fleet of thirty boats with over one hundred employees by 1970. Its leaders, Thomas Barnwell Jr. and David Jones, both natives of Hilton Head, worked around the clock to ensure that the co-op remained a sustainable venture despite the wear and tear of the work, fickle weather, and hostile market forces. With little margin for error, the threat of industrial pollution from BASF prompted the HHFC to call for more robust state regulations. By early 1970, Barnwell told reporters, “We don’t need a new industry here that would run the jobs we already have . . . out of the area.” As an economic and political force, the cooperative symbolized both the possibilities of Black self-reliance and the last vestiges of the traditional wooded commons found on Hilton Head.10

The HHFC’s success represented a visible remnant of Hilton Head’s Black past and its enduring present. Before white migrants came barreling across the Port Royal Sound in the 1960s, the island’s almost entirely African American population lived in what resident Emory Campbell described as “self-contained fishing and farming communities.” Born in 1941, Campbell recalled how most Black families owned small plots of land for farming and coexisted with northern sportsmen whose seasonal presence meant that most of the time “we could use the entire island too for getting firewood or even farming a piece of land.” As Hilton Head changed from a wooded commons to a burgeoning retreat for wealthy white retirees, these shifts not only reshaped the island’s economy but also initiated a process of Black dispossession that continued into the twenty-first century. By 1975, whites constituted about 80 percent of the population on Hilton Head, a near-complete reversal of twenty years earlier when African Americans made up around 90 percent of the population. Much as Black supporters of BASF believed that the jobs offered by the plant would help stem the tide of the Great Migration, African American islanders saw their battle in similar terms: as a way to reassert their claims to longstanding jobs and communities.11

The HHFC joined a phalanx of new groups organized by white Hilton Headers to oppose BASF. Within three weeks of the announcement, Hilton Head residents formed the Citizens Association of Beaufort County (CABC) under the banner of “Progress Without Pollution.” With an initial war chest of at least $6,000, the group’s well-connected and well-funded membership proved uniquely suited to challenge a multinational corporation with substantial political support. Most prominently, the CABC’s chairman Vice Admiral Rufus Taylor moved to Hilton Head after retiring as deputy chief of the CIA. Similarly, William Kenney settled on the island after a successful career as a general counsel for Shell Oil, where he reportedly “never lost a case” to antipollution activists. Naturally, he lent this expertise to the anti-BASF forces. Such community leaders represented a whole host of relatively new white residents who arrived on Hilton Head shores with a sense that the place was created for and thus belonged to them.12

In the frontier mythology-cum-creation narrative spun by Charles Fraser and Fred Hack, modern Hilton Head was built for people like Taylor and Kenney. Eschewing the neon lights, high-rise hotels, and kitschy roadside attractions that created a landscape of “visual pollution” stretching from Atlantic City to Myrtle Beach to Miami, Fraser envisioned Hilton Head as a seaside refuge that beckoned to the overstimulated, traffic-weary American. By design, the island’s roads would wind seamlessly through well-preserved stretches of woodlands. Reportedly, the lumberman’s son, having attained the company’s land holdings on generous terms, refused to cut down trees unless cars hit them more than twice. Other, perhaps apocryphal, tales recounted how Fraser hired a legion of barbers to groom Spanish moss so it would not weigh down the trees; along with a private security force to defend alligators and other wildlife from illegal hunting.13

The names of the roads themselves also called to mind the Arcadian vision of island life along “Belted Kingfisher Lane” and “Brown Pelican Road.” Uniformity ruled in Fraser’s Sea Pines Plantation; residents could not alter their house’s exterior, mailbox location, or landscaping without his approval. As journalist John McPhee quipped after meeting Fraser, “He is Yahweh. He is not merely the mayor and the zoning board, he is the living ark of the deed covenant.” Across the island, Fraser’s counterparts on the north side of Hilton Head found a similarly winning formula in building resorts that paired the comforts of suburban life with the aesthetics of a coastal frontier.14

For this reason, wealthy retirees and professionals flocked to Hilton Head in the 1960s. As all these newcomers understood, the island’s wilderness aesthetic provided the initial draw. From there, the sublime charms of gentle sea breezes, swaying trees, and quiet streets in exclusive neighborhoods took care of the rest. A former Philadelphia banker who retired to Hilton Head explained how “some mysterious island magic makes pleasant people [even] more pleasant.” This mystic connection between landscape, leisure, and social harmony seemed rare, lucrative, and yet tenuous. In a letter delivered to Governor McNair opposing the BASF plant, a salesman for Fred Hack’s Hilton Head Company bragged that these communities provided “nature’s therapy” in a world with “mental institutions bulging beyond capacity” due to “our industrialized and mercenary business complex.” In such personal testimonies, white residents crafted a discourse of meritocratic entitlement to enjoy nature’s beauty in an unpolluted, undercrowded place.15

Thinking they left the smog and soot of urban America behind them, the island’s newest elites were alarmed by the company’s plans. Namely, they worried about effluents discharged into estuaries, air pollution blowing east onto Hilton Head, and potential leakages or spills from oil tankers steaming into the Port Royal Sound to supply the plant. Soon after BASF’s plans became public, Fraser and his former rival Fred Hack sent an eleven-page memo to Governor Robert McNair citing internal surveys estimating that at least 90 percent of out-of-state buyers “have unpleasant personal experiences with industrial pollution ‘back home.’” Of course, “home” was a relative concept on Hilton Head. While these numbers fit the anti-BASF narrative, they also reflected the developer class’s belief that progress depended on the preservation of the “wilderness” aesthetic new residents came to expect from the island.16

With support from local, state, and national environmental groups, the anti-BASF movement gained steam by the end of 1969. For their part, white residents argued that such industrial development proved incompatible with Hilton Head’s appealing mix of a rustic yet plush aesthetic. Robert Horsey, a retired chemical engineer who lived on one of Sea Pines’s beachfront lots, explained his family’s choice to live there based on “the lack of industrialization of the area, its almost unspoiled environment, and its great natural beauty.” Similar letters poured into the offices of local newspapers and politicians. Another retired industrialist explained his opposition this way: “I’ve lived in Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit. … I know the price of industrialization. The threat of pollution is so much easier to prove after the fact than before it.” In an ironic twist of fate, many of the retiree activists doubted the promises of BASF’s top brass because they had been polluters themselves. As journalist Marshall Frady put it, Hilton Head offered “sanctuaries for retired executives and industrialists who have fled lands [to which] they have laid waste behind them in the North.”17

Meanwhile, longtime African American residents expressed concerns about the effects of chemical pollutants on both maritime industries and the fading commons economy that had defined life on Hilton Head until the recent tourism boom. Unlike their wealthy white allies, Black fishers in the Lowcountry understood pollution as victims rather than perpetrators of environmental injustice. Their repeated warnings to “look what’s happened in Savannah” came from an intimate knowledge of the costs of industrial excess that emanated from the Georgia port city. Untreated effluents from the pulp mills there proved singularly responsible for destroying the oyster industry on Daufuskie Island, a nearly all-Black community just south of Hilton Head. While white Hilton Headers echoed these concerns, they spoke of pollution as a great annoyance to their way of life rather than the mortal threat the HHFC understood it to be.18

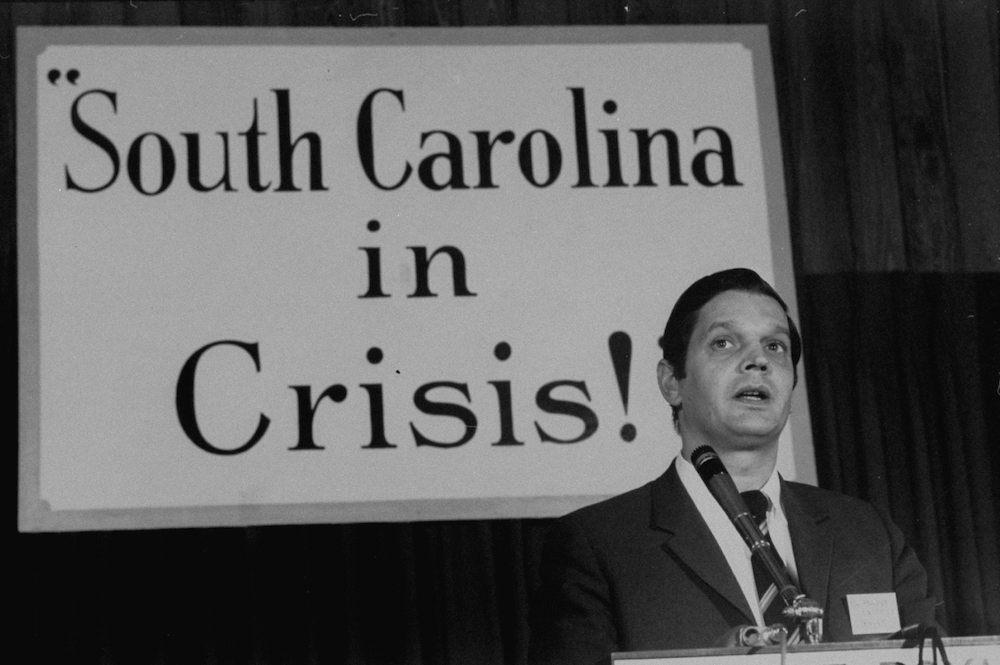

Having found eager recruits to join their cause, Hilton Headers steeled themselves for a multiyear battle against the company and its backers. In the first week of January 1970, Orion Hack—brother to Fred Sr. and vice president of the Hilton Head Company—organized a fourday, all-expenses-paid conference to call attention to the pollution threat. Although the offer of a prepaid trip to the island was in itself enticing, Hack pitched the conference to ecologists and environmental activists as an opportunity to advance their shared cause against the backdrop of “one of the few large areas of estuaries left on the East Coast still unpolluted by industrial waste.” The symposium—titled “South Carolina in Crisis!”—drew representatives from environmental organizations within the state (including the Black fishing cooperative), across the South, and from better known national groups such as the National Audubon Society and Friends of the Earth.19

However, such activists did not heap unequivocal praise on the developers’ efforts. Although they clasped hands in an uneasy embrace to voice support for the anti-BASF forces, ecologists like Barry Commoner and Joe Browder also emphasized that these issues served as only one battle in a larger war against polluters. Even more than that, they cast skeptical glances at Fraser, in particular. Soon after the symposium, one attendee who described Fraser as a “parasite” explained, “We’re not in this to bail out Hilton Head.” Similarly, a biologist from the University of South Carolina lamented, “It’s a shame what they’ve done to that island,” referencing his studies of the area’s ecosystems just a decade before the first resorts were built. Unimpressed by the island’s labyrinthine roads named for various bird species, the activists and scientists who attended the symposium were clear-eyed about the people with whom they joined forces. Fraser and Hack’s focus on preserving a wilderness landscape for human beings went against the principles of these environmentalists, but the activists operated with a righteous zeal that saw the developers not only as strategic allies but as potential converts to the broader cause.20

While plant opponents gained momentum after the conference, the pro-BASF forces expressed surprise at the swift and ferocious media campaign directed their way. In early 1970, they struggled to negotiate with the developer–fisher alliance. Upon concluding that “nothing we can say … will satisfy those who have declared their opposition,” BASF president Dr. Hans Lautenschlager asked Governor McNair to form a committee to consider how the state could beef up its pollution laws. Privately, McNair bristled at such a suggestion. But soon, he complied out of deference to the company’s top brass. While BASF’s leadership grew nervous about the gathering storm of negative publicity, the governor hoped these meager concessions would satiate the opposition long enough for him to launch a public relations counteroffensive.21

Despite earlier attempts at negotiation, state officials and local boosters lambasted what one local journalist termed the “fat cat refuge” developers built on the island. Namely, boosters characterized Fraser and his ilk’s criticism of “incompatible” industries as nothing more than naked self-interest disguised as ecological concern. After touring BASF plant in Europe, state Senator James Harrelson scoffed at their protests, saying, “I don’t think they’ll ever find what they call ‘compatible industry’. … They probably wouldn’t like to see any industry, even an ice cream pie factory!” An editorial in the Charleston News and Courier also needled Fraser’s situational ethics. “When a developer buys a primitive sea island, cuts the timber, drains the marshes … and builds houses, motels and golf courses, the conservationists have a fit,” but “when someone tries to build a factory near the developer’s island, the developer and his new population have a fit.” In a letter to a Beaufort newspaper, one local farmer charged that Hilton Headers wanted “to make a rich man’s preserve of the entire area,” since they would be “horrified at the prospect of having to live in proximity to several thousand common working people.” This line of discourse was part and parcel of a broader strategy to paint the island’s developers as snobbish newcomers who gave no thought to the economic plight of the area surrounding their plush resorts.22

In contrast to claims that the BASF opposition represented the petulant clamoring of a privileged elite, the HHFC seized a pivotal role in the movement. In February 1970, the Black shrimpers joined with two smaller seafood cooperatives to file a lawsuit against BASF, arguing that the chemical company failed to comply with the new requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This announcement signaled the beginning of the end for the plant’s proponents. J. Wilton Graves, a local political boss, lashed out at the cooperative for “allowing themselves to be influenced by legal brainstorming and selfish interests.” Contrary to Graves’s claims, such statements missed the long game strategy adopted by Barnwell, Jones, and the HHFC brain trust. Although white resort owners did underwrite their lawsuit, the HHFC regarded the arrangement as temporary but necessary in a broader campaign for economic self-reliance and community preservation. For some African American residents, the cooperative offered the best way to reassert their dwindling presence on the island.23

Undoubtedly, white Hilton Headers cheered the increased visibility of Black fishers. Although tourism accounted for most of the island’s economic impact, the symbolic presence of Blackrun fishing operations provided a more poignant talking point for their white neighbors. For example, a full-page advertisement in the New York Times—paid for by a statewide environmental group founded by the Hack family—featured a picture of Black fishers working on their boats. The ad’s text warned that the plant would ensure that “these proud, hard-working fishermen of today will be unemployed or on welfare tomorrow causing grave unemployment in this poverty pocket.” Meanwhile, other white island residents understood the role of African American maritime work in a more paternalistic sense. Walter Greer, a prominent Hilton Head artist whose landscapes of Lowcountry life depicted, in his words, “the negro performing tasks indicative to his skills in this part of South Carolina,” sent a letter to the governor protesting the plant. After citing his paintings, Greer asserted that “their life and pleasure comes from the tidal waters” and that “there is no occupation available to the underskilled individual when his aquatic livelihood is obliterated.” By deploying the nostalgic imagery of Black men working on the water, white islanders portrayed a cooperative made up of quaint figures that fit their Arcadian vision of life on an unsullied island. Yet, if anyone could claim a right to belong on Hilton Head, it was the Gullah communities of Black islanders who had lived there long before BASF came calling.24

Refusing to be dismissed by their white neighbors, some African Americans voiced support for BASF. These efforts reached a fever pitch in spring 1970 after Interior Secretary Walter Hickel intervened to stop the project temporarily. Just across the bridge from Hilton Head in the town of Bluffton, dozens of Black residents who formed the Bluffton Progressive Club got right to the point in a statement blasting the island’s developers: “Our labor[s] at low wages have contributed to Mr. Hack’s and Mr. Fraser’s success.” Meanwhile, local naacp chapters organized rallies across the area. One protest organized by local Black ministers began fifty miles to the west in Hampton County before taking a bus trip to Hilton Head to protest “the rich people … who are stopping [the plant].” In response to mounting anger over Hickel’s orders, such protests grew more frequent and intense, culminating in the raucous demonstration outside Fraser’s office in June 1970.25

Support for BASF among these African American communities grew out of a desire to ensure their survival through economic development. Although these groups recognized the value of independent Black businesses like the cooperative, they also asserted that putting all their eggs in the basket of traditional maritime or agricultural industries was foolish after nearly a decade of Black land loss and with better guarantees for equal hiring in the manufacturing sector. Although groups like the Progressive Club gave full-throated support to the plant, they shared a common desire with their fellow Gullah communities to preserve Black places in the Lowcountry.

On the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970, the HHFC and white Hilton Headers pressed their case with federal policymakers. The crown of the cooperative’s fishing fleet, a forty-one-foot trawler named Captain Dave, sailed up from Hilton Head to the Chesapeake Bay and through the mouth of the Potomac River, where the crew presented officials from the Department of the Interior with a petition bearing forty thousand signatures of people opposed to the plant.

Organized by one of Sea Pines Company’s public relations gurus, the “cruise” capped off months of organizing, petitioning, and debating the compatibility of the BASF plant with the changing Lowcountry landscape. Against the fierce headwinds of this unusual environmental movement, BASF’s plans sputtered before coming to naught in the final months of 1970.26

Over the next three years, two similar companies expressed interest but ultimately passed on the same industrial site with considerably less fanfare than BASF. First, a Houston-based petrochemical company considered erecting a smaller plant on Victoria Bluff. Preferring not to risk a public relations debacle, they gave way to the Chicago Bridge and Iron Company, which hoped to build a natural gas refinery there. Although CBIC won backing from more local African American leaders and gave similar assurances to limit pollution, their plans never got off the ground either. For their part, BASF decided to relocate the facility intended for Victoria Bluff to Geismar, Louisiana, adding another chemical plant to the sordid landscape of that region’s “Cancer Alley.”27

The victorious alliance of the HHFC, Sea Pines, and the Hack family saw each at the arguable peak of their influence. David Jones, the co-op’s captain, continued to serve on the Beaufort County Council until 1977. According to Thomas Barnwell Jr., the group continued to meet its production goals over the next five years. However, the combined toll of the 1970s oil shocks, increased regulations to protect marine life, and competition from Pacific markets undermined the cooperative. Closer to home, cooperative members also cited changes in local fishing grounds that pushed them further from the shoreline and away from the most productive shrimping areas.28

Over the next two decades, as the competition between developers grew increasingly fierce in the face of economic troubles, the mostly working-class Black islanders struggled to keep their homes and communities on Hilton Head. Meanwhile, an overextended and cash-strapped Sea Pines did not collapse, but Fraser’s once quasi-dictatorial control over Hilton Head was shattered. As the island became an increasingly contested political environment in the early 1980s, the three groups that joined forces to defeat BASF—developers with Black and white residents—turned increasingly combative as the local population continued to grow, becoming ever more white and affluent.

Although the natural environment has suffered under the crushing weight of Hilton Head’s residential growth in the last sixty years, those losses do not compare with the losses of Black islanders. After falling to 15 percent of the island’s population in 1980, African Americans today make up only 7 percent of Hilton Head’s population. In addition to being priced out of multigenerational land holdings, Black islanders lost homes due to rising property values and the exploitation of heirs’ property laws that deprived them of due process or equitable compensation.

In the Lowcountry and across the South, most African American landowners did not pass down property through wills, a legacy of the intergenerational distrust toward a duplicitous legal system. Such lands became “heirs’ property” or shared between the deceased’s immediate relatives. Loopholes in state laws made it possible for developers to force a “partition sale” on any heirs’ property if only one relative agreed to sell—almost always at below-market values for semicoastal land—no matter if they lived hundreds of miles away from the property in question. Although recent legislation has sought to fix some of these loopholes, the damage has already been done. The efforts of Black native Emory Campbell and the Penn Center, a longtime local incubator for social justice activism, did stem the tide of this trend to some extent. However, Campbell estimated that by 1980 Black Hilton Headers had lost around one thousand acres of land to tourism-related development.29

Despite the crucial role Black communities played in protecting Hilton Head’s landscape and livelihoods, the presence of more and more white newcomers means the ancestral ties of many Gullah communities have become increasingly frayed. For many who took work in the burgeoning hospitality and tourism trades alongside the area’s growing Latinx population, the costs of living on the island pushed them inland toward the rural towns along Interstate 95. Since the early 1980s, local governments have provided bus transit for these workers (the invitingly named Palmetto Breeze), a nearly five-hour round-trip commute to their jobs on the island. Unable to make ends meet on land where the average home price reaches nearly half a million dollars, these workers—with deep roots on the island—still provide the essential, taxing labor that sustains Hilton Head. In ways often unseen by the casual tourist, this island belongs just as much to the Black communities of the Lowcountry. Economic inequity has certainly stretched the physical ties of African Americans from ancestral coastal communities like Hilton Head. With a still shrinking presence on the island, these strained ties necessitated numerous imaginative acts of belonging that assert a very real claim on the land that is today largely occupied by wealthy whites.

Out of these dispossessions, Gullah Geechee activism has been emboldened and gained a wider audience over the last three decades. Thanks to the tireless efforts of the Penn Center, Emory Campbell, and Congressman James Clyburn, the federal government established the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor in 2006 along the southeastern coast. In recent years, leaders like Queen Quet of the Gullah Geechee Nation have pushed environmental activists to recognize that climate change not only poses an existential threat to local ecology but to the sacred cultural heritage of Black communities as well. Through partnerships with predominantly white environmental groups like the Coastal Conservation League, African Americans in the Lowcountry continue to push for a recognition that the potential losses from sea-level rise go far deeper than eroding property values for wealthy coastal homeowners. As unyielding advocates of a sustainable future for Black Sea Islanders, this legacy of place-based activism reminds us that the past, present, and future of Hilton Head is indivisible from the African American lives and communities that have known and loved and labored on its land and waters.30

This essay first appeared in the Human/Nature Issue (vol. 27, no. 1: Spring 2021).

Madison W. Cates is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Florida and an adjunct instructor at Santa Fe College in Gainesville, Florida. He holds degrees from Gardner-Webb University, North Carolina State University, and the University of Florida. His essay in this issue draws from his larger research on race, environmentalism, and land loss in the modern South.NOTES

- South Carolina Development Board Press Release, June 15, 1970, Governor Robert McNair Papers (hereafter cited as McNair Papers), box 74, folder: “BASF May–December, 1970,” South Carolina Political Collections, Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina (hereafter cited as SCPC); William D. Bryan, “Poverty, Industry, and Environmental Quality: Weighing Paths to Economic Development at the Dawn of the Environmental Era,” Environmental History 16, no. 3 (July 2011): 512–513.

- “Population More than 3000 Here,” (Hilton Head) Island Packet, July 9, 1970; Michael N. Danielson and Patricia R. F. Danielson, Profit and Politics in Paradise: The Development of Hilton Head Island (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995), 13–16.

- John D. Pomfret, “A Rural Slum Cuts across South,” New York Times, March 3, 1964; BASF Corporation to The Honorable Walter J. Hickel and J. J. Simons, November 21, 1969, and E. T. Borda to James Konduros, undated position paper, McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “BASF: March–November, 1969,” SCPC; BASF Press Release, October 1, 1969 and Curtis B. Flory to J. D. Little Jr., July 10, 1969, McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “BASF: March–November, 1969,” SCPC.

- Oliver Wood Jr. et al., The BASF Controversy: Employment vs. Environment (Columbia: Bureau of Business and Economic Research, University of South Carolina, 1971); Arthur Simon, “Battle of Beaufort,” New Republic, May 23, 1970, 13; Alan Ternes, “An Introduction to the Setting and Characters of the Tragical Farce or Farcical Tragedy of Victoria Bluffs, S.C.,” Natural History 79 (April 1970): 9–17. William Bryan’s indispensable article “Poverty, Industry, and Environmental Quality” shapes much of my thinking about this episode, though my work differs in focus and emphasis rather than conclusions. Although the BASF affair is certainly a prime example of the tensions between the War on Poverty and environmental activism, I situate its importance in relation to more localized trends of Black land loss and heritage depletion.

- Paul Good, “Of Hookworms and Spanish Moss,” New South 23, no. 1 (Winter 1968): 85–97; Robert Coles and Harry Huge, “Strom Thurmond Country,” New Republic, November 30, 1968, https://newrepublic.com/article/99653/strom-thurmond-south-carolina-poverty; David Nolan, “Letter to the Editor: The Hunger Doctor,” New York Review of Books, March 11, 1971.

- Bob Thompson to J. D. Little Jr., November 12, 1969, McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “BASF: March–November, 1969,” SCPC; BASF Corporation to The Honorable Walter J. Hickel and J. J. Simons, November 21, 1969 and E. T. Borda to James Konduros.

- “An Editorial,” Beaufort Gazette, December 11, 1969, BASF Vertical File, Beaufort District Collection, Beaufort Public Library, Beaufort, South Carolina (hereafter BDC).

- Arthur Simon, “The Battle of Beaufort,” New Republic, May 23, 1970, 12.

- Frazier quoted in Betsy Fancher, “Special Report: A New Plant Meets a New Age,” South Today, 1970, 4, BASF Vertical File, BDC; Charles Simmons quoted in Simon, “Battle of Beaufort,” 13.

- Barnwell quoted in Bayard Webster, “Carolina Plan to Build a Plant on Unspoiled Coast Arouses Protest,” New York Times, February 1, 1970.

- Emory Campbell, interview by Robert Korstad, 1992–1994, DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy, Duke University, Durham, NC; Fritz R. Simmons, “Island Frontier Off Georgia’s Coast,” New York Times, April 29, 1956; Daniel J. Vivian, A New Plantation World: Sporting Estates in the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1900–1940 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018); June Manning Thomas, “Blacks on the South Carolina Sea Islands: Planning for Tourist and Land Development” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1977), 60–63.

- Bob Thompson to J. D. Little Jr., October 24, 1969, McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “March–November, 1969,” SCPC; Simon, “Battle of Beaufort,” 13; Bryan, “Poverty, Industry, and Environmental Quality,” 499.

- John McPhee, Encounters with the Archdruid (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1971), 91–92; Angela C. Halfacre, A Delicate Balance: Constructing a Conservation Culture in the South Carolina Lowcountry (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), 172–174.

- McPhee, Encounters with the Archdruid, 89–94, quote on 94.

- Danielson and Danielson, Profit and Politics, 100–102; George C. Bjork to Governor Robert McNair, December 31, 1969, McNair Papers, box 75, folder: “BASF Letters: Con, 1969,” SCPC.

- Fred Hack and Charles Fraser Memo to Governor McNair, November 29, 1969, 7–8, McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “BASF: March–November, 1969,” SCPC.

- Robert G. Horsey to Governor Robert McNair, December 23, 1969, McNair Papers, box 75, folder: “BASF: Letters–Con, 1969,” SCPC; retired industrialist quoted in Marshall Frady, “The View from Hilton Head,” Harper’s Magazine, May 1, 1970, 104 (emphasis in original), 105.

- Barnwell quoted in Webster, “Carolina Plan to Build on Unspoiled Coast Arouses Protest”; Robert Horsey to Governor Robert McNair, SCPC. For a detailed report on the environmental and ecological damage done by the paper industry in Savannah, see James M. Fallows, The Water Lords: Ralph Nader’s Study Group Report on Industry and Environmental Crisis in Savannah, Georgia (New York: Grossman, 1971).

- Citizens Association of Beaufort County, Conservation Symposium: South Carolina in Crisis, January 4–7, 1970, BASF Vertical File, BDC; Bryan, “Poverty, Industry, and Environmental Quality,” 501–506.

- University of South Carolina biologist quoted in “Environment: Fight at Hilton Head,” Newsweek, April 13, 1970, 72; Ternes, “An Introduction,” 9–17, quote on 12; McPhee, Encounters with the Archdruid, 77–96.

- Dr. Hans Lautenschlager to Governor Robert McNair, December 15, 1969, McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “BASF: December 1969,” SCPC; Robert McNair to Dr. Hans Lautenschlager, January 15, 1970, McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “BASF: December, 1969,” SCPC.

- “Ashley Cooper: Doing the Charleston,” News and Courier, January 11, 1970, BASF Vertical File, BDC; L. J. Williams Letter to the Editor, Sea Islander, January 29, 1970, copy included in McNair Papers, box 74, folder: “BASF: January 1970,” SCPC. Although Jonathan Daniels criticized McNair and the pro-BASF forces (even once describing them as “chemical stormtroopers”) the famed editor who lived in Fraser’s Sea Pines Plantation and founded Hilton Head’s Island Packet newspaper also reserved biting criticism for the developer in his public and private writings. Pro-BASF white leaders in Beaufort picked up on the “fat cat” trope in similarly blunt terms. Jonathan Daniels to Henry Fairlie, January 24, 1971, Jonathan Daniels Papers folder 1828: “January 1971,” Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For a clear example of the “incompatibility” argument, the Hilton Head Rotary Club president William N. Cork wrote a letter to the editor of the Beaufort Gazette in December 1969 saying, “The appearance of a heavy industrial plant … would be completely incompatible with and inimical to the area as a vacationland and resort center.” William N. Cork Letter to the Editor; and J. P. Harrelson quoted in “Sen. Harrelson Rejects Fears of Pollution,” Beaufort Gazette, December 11, 1969, BASF Vertical File, BDC.

- Graves quoted in Barr Nobles, “Moratorium Looming on Suit against BASF,” Savannah Morning News, February 12, 1970.

- “Of Marsh & Men and the Right to Life,” New York Times, 1970, BASF Vertical File, BDC; Walter Greer to Robert McNair, December 17, 1969, McNair Papers, box 75, folder: “BASF Letters: Con, 1969,” SCPC. On Orion Hack’s role in creating Concerned South Carolinians for a Better Environment, see Bryan, “Poverty, Industry, and Environmental Quality,” 507–508.

- Bluffton Progressive Club, “We Need BASF!,” Beaufort Gazette, December 10, 1969; Rev. Walter Burson quoted in Simon, “Battle of Beaufort,” 13.

- Bryan, “Poverty, Industry, and Environmental Quality,” 510–512; “Shrimp Co-Op Makes Blacks Their Own Bosses,” Ebony, November 1969, 107–108.

- Bryan, “Poverty, Industry, and Environmental Quality,” 514.

- On the other attempts to industrialize Victoria Bluff, see Danielson and Danielson, Profit and Politics, 156–158; and “Hilton Head: A Contrast of Cultures,” New York Times, December 30, 1973. For a short overview on the rise and fall of the fishermen’s cooperative, see Sherry Conohan, “Site of Planned Rowing and Sailing Center Special for Many Native Islanders,” Hilton Head Monthly, October 2013, 90–91.

- US Census Bureau, 1980, 2010 Census of Population, South Carolina, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC; Thomas, “Blacks on the South Carolina Sea Islands,” 62. According to conservative estimates in the early 1980s, around one-third of all Black-owned land in the South was considered heirs’ property. As recently as 2019, one report found that around 76 percent of all African Americans in the United States did not have a will. Bill DuPre, “Heirs Property Presents Major Legal Problems,” Savannah Morning News, February 18, 1975; Cindy Thames, “Conference Probes Black Land Plight,” Savannah Morning News, February 18, 1975; June M. Thomas, “Hilton Head Report: No Place in the Sun for the Hired Help,” Southern Exposure 10, no. 3 (May–June 1982): 36; and Lizzie Presser, “Their Family Bought Land One Generation After Slavery. The Reel Brothers Spent Eight Years in Jail for Refusing to Leave It,” ProPublica, July 15, 2019, https://features.propublica.org/black-land-loss/heirs-property-rights-why-black-families-lose-land-south/. For examples of recent reforms to protect heirs’ property, see LaTonya Lipscomb Smith and Trinity Turinetti, “Preserving Wealth with Uniform Partition Heirs’ Property Act,” Jacksonville Daily Record, September 3, 2020, https://www.jaxdailyrecord.com/article/preserving-wealth-with-uniform-partition-heirs-property-act. For the status of such reforms in state legislatures, see April Simpson, “Racial Justice Push Creates Momentum to Protect Black-Owned Land,” Pew Trust News, September 21, 2020, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/09/21/racial-justice-push-creates-momentum-to-protect-black-owned-land. It should be noted that in the early 1970s, Charles Fraser and the Sea Pines Company set up a legal services branch to help Black landowners fix titles that were unclear due to the lack of a will or subject to other heirs’ property issues. However, African Americans greeted such an offer from the Fraser real estate empire with suspicions. As one leader in the local NAACP chapter deemed it, the program appeared more like “a scheme to get black property in the disguise of help.” Emory Campbell quoted in Mark Pinsky, “Hilton Head Report: Sea Island Plantations Revisited,” Southern Exposure 10, no. 3 (May–June 1982): 34.

- Despite the successful effort to establish the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor and curb the effects of “heritage depletion” on the Sea Islands, the federal government has refused to heed activists’ requests for funding or loan programs to help longstanding Black property owners hold onto their land. Melissa L. Cooper, Making Gullah: A History of Sapelo Islanders, Race, and the American Imagination (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 188–199.