Lake Charlotte started to bother me one summer while I was working on a freelance project with a nonprofit called Trees Atlanta. Somewhere in the organization’s sunny building, I saw a poster illustrating Atlanta’s tree canopy—a kind of heat map of trees that needed saving. Red-orange blocks downtown sprawled into yellow-green neighborhoods and green parks. I studied it while waiting for my meeting to begin, amused to see the typical city map in reverse, defined by its undeveloped pockets instead of highways. The deepest green was in the southeast corner of the city, an emerald parcel bounded by a landfill and I-285. I knew what it was—Lake Charlotte Nature Preserve—but I had never been there.

According to this map, the forest was larger and greener than Piedmont Park and Grant Park combined. I tried to picture it and came up blank. All I remembered was the forbidding landfills and barren truck lots clustered in the elbow of the interstate. Old junkyards, strip clubs, and public housing projects scattered along Moreland Avenue. Long before I knew about zoning, I recognized the land-use pattern that sited poor Black neighborhoods alongside industrial districts. For most of my life, I had avoided this area, home, apparently, to the single largest concentration of intact tree canopy left inside the city limits.

As a Southside native and a generally outdoorsy mom, I was embarrassed by this gap in my mental map of Atlanta. I would rectify this immediately. Take the kids for a sweaty ramble around the lake and document it on Instagram. This weekend. But as I mapped out our first trip to Lake Charlotte, only eight miles from home, I couldn’t find any information on the city Office of Parks website. No photos or trail reviews, only curious explorers sharing rumors on message boards. There were places where you could sneak through the fence, they said, but no public access.

All the maps were wrong. They showed Lake Charlotte Nature Preserve as a green rectangle with a thin, whale-shaped lake in the center. The blunt face of the whale must have been a dam once, its body a flooded valley. But the satellite image showed a meadow, no lake. Stymied by these findings, I let summer turn to fall, then the holidays arrived without an expedition to Lake Charlotte. A couple more summers went by. Every time I saw it labeled falsely on a map, it bothered me more. Was it ever a public park? Who was Charlotte and what happened to her lake? And just what was behind that fence?

The recent history of the land was easy to find online in property records and local news sites. Fulton County listed Lake Charlotte’s owner as Waste Management, Inc., same owner of the adjacent parcel in DeKalb County, the monumental Live Oak landfill. Live Oak opened in 1986 and it bought the forest next door in 1989, anticipating future expansion.1

Live Oak always struck me as a comical name for a dump, devoid, as it was, of trees and living things. As a child in the ’90s, commuting between my dad’s and mom’s houses, I learned to crank up my car window as soon as I spotted the grassy ziggurat that loomed on the horizon and punctured the dark with spooky blue flares. But even with the window up, the sour milk stink of the dump lingered in the car well past businesses like Hub Cap Daddy and The Foxy Lady.

I remember reading about the controversy surrounding the landfill. It was located in DeKalb County, but the smell traveled for miles, into neighboring Atlanta and Clayton County neighborhoods, where residents gradually stopped hosting backyard cookouts, stopped leaving their windows open at night. In 1993, when Waste Management applied for a permit to expand into the Lake Charlotte property, Atlanta residents—most of them Black working-class homeowners—organized in protest. Live Oak was one of several enormous “solid waste handling facilities” already dominating Southeast Atlanta and southwest DeKalb County. The city denied the permit and residents celebrated.2

Instead of expanding outward, the landfill rose like a loaf of bread—a rotten rectangle squeezed straight by the county line and the interstate. The Lake Charlotte property was the only buffer between the reeking dump and backyards in South River Gardens, a predominantly Black neighborhood. By 2000, Live Oak started accepting “sludge,” a byproduct of sewage treatment plants that is typically converted to fertilizer, and the smell became unbearable. Live Oak’s waste handling was both sloppy and illegal, which ignited further protests.3

Instead of expanding outward, the landfill rose like a loaf of bread—a rotten rectangle squeezed straight by the county line and the interstate.

Southwest DeKalb residents appealed to their legislators and rallied at the state capitol, framing their burden as a case of environmental racism. In 2003, when Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division finally ordered Live Oak to shut down operations, the landfill was already full to capacity and over a decade past its original life expectancy. In 2007, Waste Management started harvesting methane from the capped landfill, but held onto Lake Charlotte. For decades, the two hundred–acre Lake Charlotte property remained undisturbed and mislabeled on maps, a forgotten forest with a padlock on the fence.4

I had to dig into the city’s planning documents from the late seventies, comprehensive plans and land-use plans and annual reports from the Bureau of Parks and Rec with sexy typography and optimistic sketches, to find proof that, once upon a time, briefly, Lake Charlotte Nature Preserve was exactly what it sounded like: a public park with a lake in the center.

This inner-city campground was the brainchild of Ted Mastroianni, Mayor Maynard Jackson’s “fast moving and aggressive” director of parks and recreation. Recruited from New York City’s parks department, he joined Mayor Jackson’s team in 1975 and declared they would be “balancing the park system,” by acquiring and protecting half a dozen wooded tracts across the Southside. “What seems to excite Mastroianni the most,” according to the Atlanta Constitution, “is the acquisition of natural open spaces.” In the 1975 annual report, he appears with bushy hair and a double chin over his wide necktie and lapels, captured mid-laugh so you can see his molars. He was only thirty-six years old.5

“We want areas where you can walk and lose yourself, rather than having to drive two hours to the North Georgia mountains,” Mastroianni told the reporter. “If we develop good parks and campsites inside the cities, maybe people will stop hating the cities.” I could picture this young New Yorker flying into Atlanta, gazing down upon the Southside with that big grin. From a planner’s eye view, it seemed like a great idea to preserve these forests before they were swallowed by development. In 1977, Mastroianni marshaled federal and state grants to purchase the placid ten-acre Lake Charlotte and forty acres surrounding it. He told reporters that the park would be “open as soon as the paperwork is completed.” When Mastroianni said, “Practically no improvements are required. It just becomes a park,” he underestimated what it would take to make an inner-city wilderness feel appealing and safe.6

Despite these visionary investments in the city’s park system, by the 1980s, the area was at a tipping point. Growing landfills and declining public housing projects surrounded Lake Charlotte. There’s a term for infrastructure and industrial sites like landfills that nobody wants in their backyard—lulu, or locally undesirable land use. DeKalb County was committed to stashing industrial lulus here, near I-285 and the new interstate bypass I-675, a development trend that eventually eclipsed Mastroianni’s idea of a fun family getaway.7

In 1986, the city scrapped the entire project, saying that “the unattended nature of the park attracts illicit acts.” They sold the land at a loss to a private developer named Herman Lischkoff. I struggled to imagine the context—the crisis, really—in which such a disposal of public lands could be done without scandal. But the more I read about Atlanta’s creeks and forests in the 1980s, the more I learned about the infamous Atlanta child murders. For a nightmarish period between 1979 and 1981, a Black child went missing in Atlanta nearly every month. Twenty-nine cases were linked to one killer, and many of the victims’ bodies turned up on riverbanks and vacant wooded lots of Southside Atlanta.8

On November 1, 1980, the tiny body of Aaron Jackson Jr., age nine, was spotted by a passerby from the South River Bridge, one block north of Lake Charlotte Nature Preserve. I was shocked to come across a photo of the crime scene on an amateur true crime website that revealed brown ankles in black sneakers laid out on stone riprap. “I wish I hadn’t seen the body,” Jackson’s father told the newspaper after identifying the child at the city morgue. “That’s what I see every time I close my eyes.”9

The ongoing horror of those killings profoundly affected Atlantans’ perception of urban waterways and wilderness for years. The murders deepened Whites’ fears about the dangers of the inner city, accelerating White flight into the suburbs. And an entire generation of Black residents learned to fear and avoid Atlanta’s forests and rivers. In 1981, Lake Charlotte made headlines when a body was found in the lake. A twenty-seven-year-old lawyer named William Brown was beaten and dumped by muggers from the Cabbagetown neighborhood. Officially, the city breached Lake Charlotte’s earthen dam and drained the lake in 1982 in compliance with the US Safe Dams Act. Unofficially, it was haunted.10

Lischkoff combined the Lake Charlotte parcel with 163 more acres, citing vague plans to create an industrial park. After a long and losing battle to get the parcel rezoned, it was he, not the city, who sold what was once a public nature preserve to Waste Management.11

Lake Charlotte Nature Preserve in April 2019 when my colleague Ryan Gravel, an urban planner, got a key to the padlock. He was working on a project for the city, a very Mastroianni kind of plan to preserve the remaining forests of Atlanta. Using the heat map from Trees Atlanta and penalty funds paid by developers who cut down trees, the city was looking to buy forested land and make it publicly accessible. Forty years after the first attempt, this nature preserve seemed like a viable project again.12

I drove to Lake Charlotte one warm afternoon with all these stories in my head, bubbling over with Internet research and rumors about a place I had never actually seen. Stacy Funderburke, an attorney with the Conservation Fund who had been working on behalf of the city to buy the property from Waste Management, met Ryan and me on the corner of Forrest Circle. This was one of the Black neighborhoods that fought the landfill and won. I parked in front of a modest, brick split-level and felt conspicuously White piling into Stacy’s Subaru. Would these residents benefit from a nature preserve across the street? Or would it mean a different kind of unwelcome traffic?

We pulled into the gate near the South River Bridge and startled a trio of deer crossing Forrest Park Road. Once inside, we stepped over giant truck tires and a scrum of fresh litter. Hunters snuck in, Stacy told us. They cut the lock off a few times a year and the tire dumpers followed.

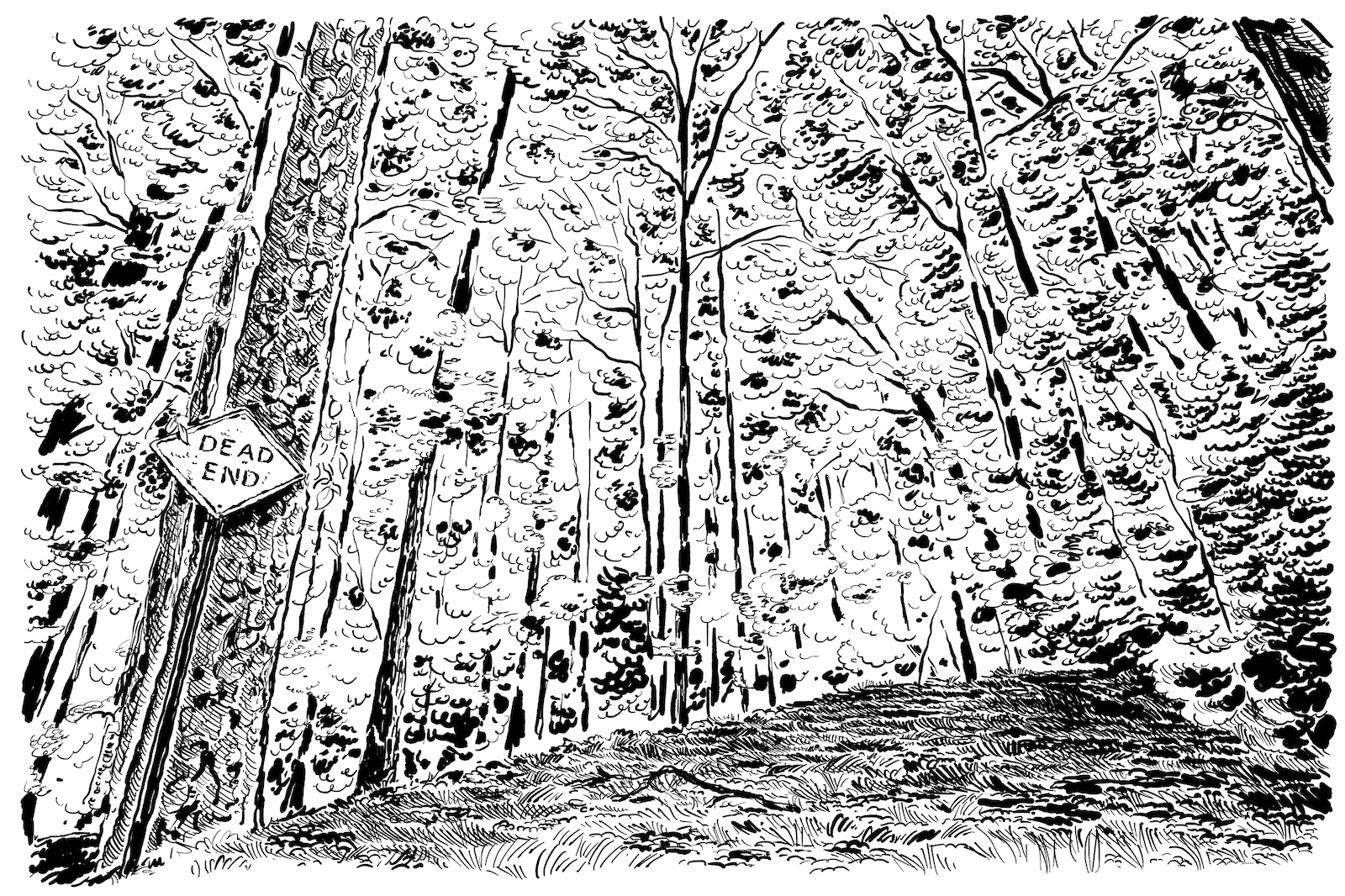

With the gate locked behind us, we walked into the trees, following the rutted remains of “Woodsey Way,” once a residential street leading to Lake Charlotte’s lakefront estates. Up ahead, a pile of tires blackened the forest floor, as if children made a game of rolling downhill tucked inside them. The sounds of the outside world blurred with each step. Beech leaves cast corrugated shadows, blocking out the sky. Stacy pointed out a shagbark hickory, a tree that appears as the shaggy Gandalf of the forest. My contribution was the name of this ghost road, last paved in the 1960s.

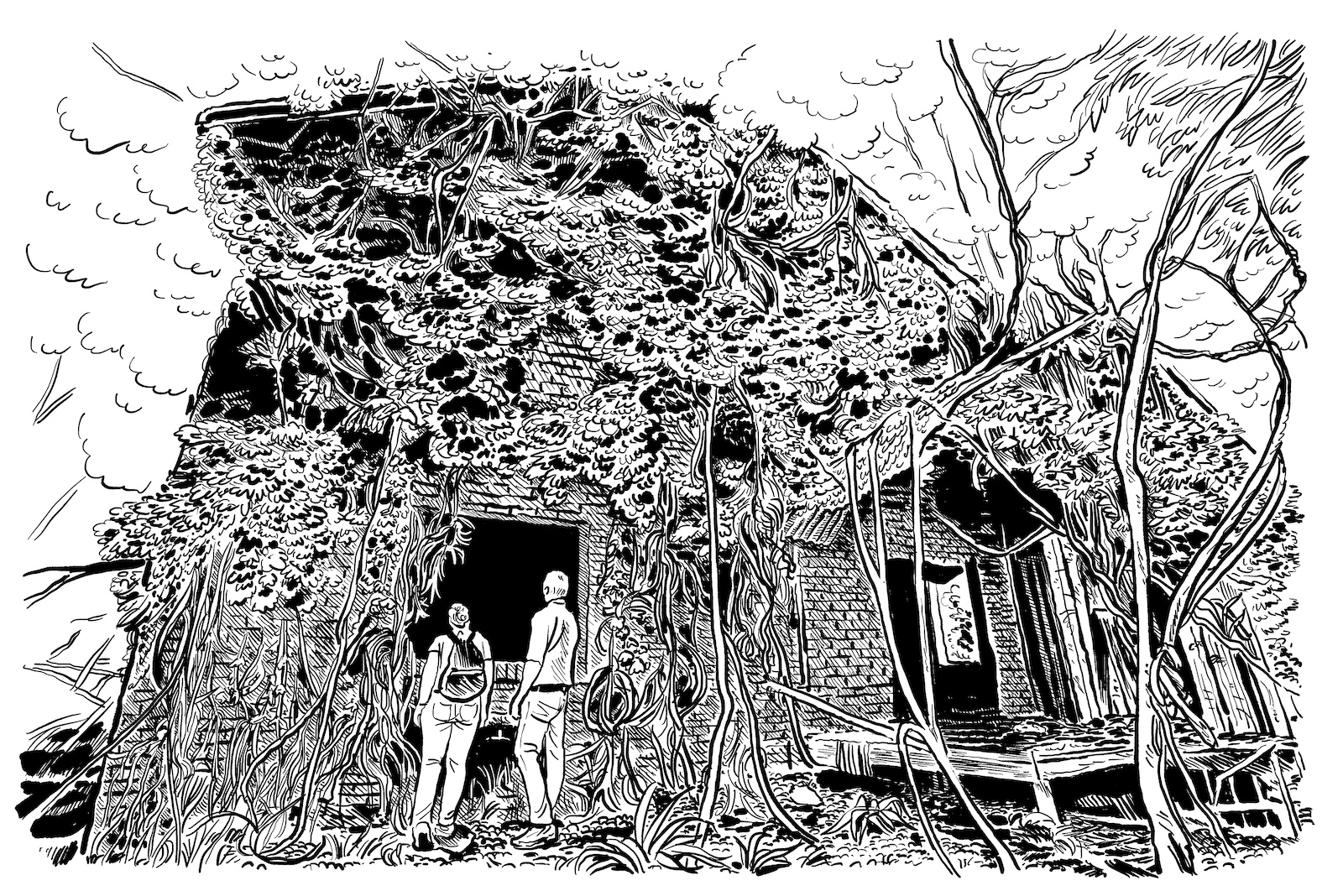

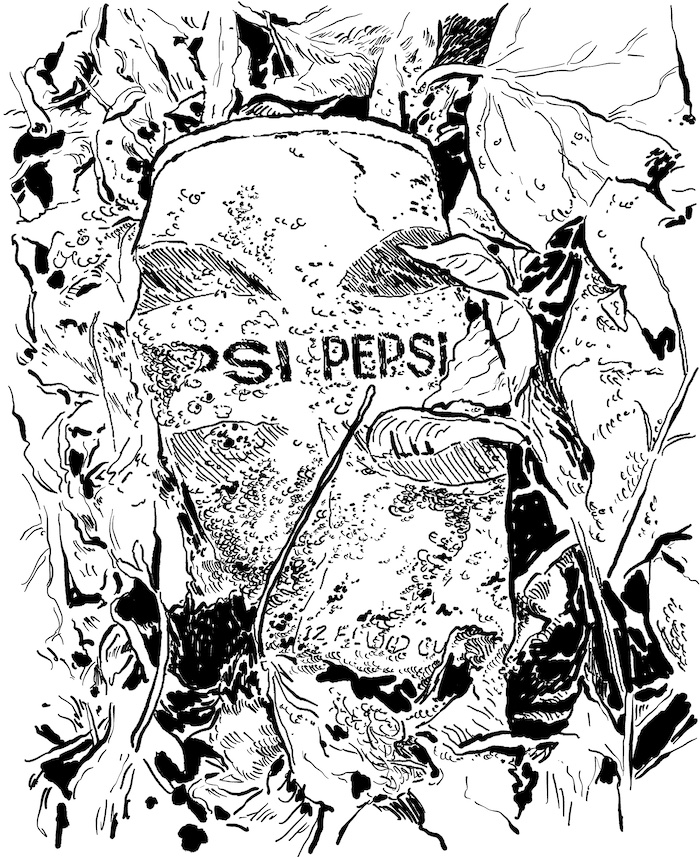

Eyeing the diameter of the beech trunks, Stacy guessed some of them were 175 years old. He took photos of Ryan and me gazing up, dwarfed by poplars as we ventured down the trail. At a moss-covered Dead End sign, we continued south on Lake Drive. Ryan and I peeked inside the ruins of a two-story brick lodge. No sign of squatters in the rain-collapsed rooms. We speculated about who lived here and when. By the front porch, I toed a leather roller skate, also covered in moss. Based on the pop-tops on the beer cans and typeface for Diet Pepsi, the litter here was late-’80s vintage. Postapocalyptic scenes like these are why The Walking Dead is filmed in Atlanta. Humid overgrowth devours a house in no time.

Postapocalyptic scenes like these are why The Walking Dead is filmed in Atlanta. Humid overgrowth devours a house in no time.

Further down the road, Stacy spotted a great horned owl moving from tree to tree and quietly screwed a telephoto lens onto his camera. I wandered over to the stone gate of a once grand lake house, testing the ground for hidden wells. Right there among the ruins, I pulled up a historic topographical map on my phone. Structures dotted the road here in 1928, overlooking “Mount Manor Lake.”13

Later, I would spend countless hours sifting through newspaper archives and old maps, trying to learn who developed Mount Manor Lake in the 1920s. Dr. R. F. Ingram came up several times. He was a prominent Atlanta dentist, businessman, politician, “convicted bootlegger,” and president of the Mount Manor Estates Fishing Club. At some point, Woodsey Way became Ingram Drive.14

Eventually, reading obituaries and society pages, I found a Charlotte in the Ingram family. Miss Charlotte Sage, a wealthy, well-documented Ansley Park debutante of the 1937 season, was Dr. R. F. Ingram’s only granddaughter. For years, her outfits and social “gaieties” were breathlessly chronicled in the Atlanta society pages. Even after Miss Charlotte’s wedding to a naval officer in 1948, the papers continued to cover the celebrity couple.15

The notice of Charlotte’s funeral in 1956 surprised me. She was only thirty-seven years old, without a husband or heirs. It said nothing about how she died, and my imagination filled the blank space with a tragic scandal. Her named vanished from the newspapers, but by 1960, Lake Charlotte appeared on Atlanta maps, a watery tribute that outlasted the lake itself.16

As a girl, did Charlotte love this place? I wondered about this as I balanced on a log to cross the creek. I could hear Ryan’s and Stacy’s voices moving up the hill towards the landfill. My T-shirt clung to my back as I hiked up the shady hillside, past holly bushes and boulders scarred with mossy divots. Thousands of years before Muscogee-speaking people settled here, between 1500 and 600 BCE, people sat on this hillside carving bowls out of the dark green stone. Geologists called it Soapstone Ridge, and archaeologists in the late 1970s made a heroic effort to document the ancient quarry sites and recover priceless stone artifacts before they vanished under landfills and truck lots.17

At the top of the hill, the sound of whirring machinery broke the spell. Ryan and Stacy were taking photos of the landfill’s blank backside, a grassy expanse pocked with shiny, expensive-looking machinery. No doubt, a surveillance camera somewhere was watching us. I held my breath until I was hidden by the trees again. I spotted at least three strange devices before I googled the name for them—piezometer, an instrument that measures the pressure of groundwater. It reminded me that the Waste Management’s greenspace served a purpose, filtering and buffering contaminants from Live Oak. We joked, uneasily, about the chemical odor of the landfill, and what might be in the water.

The afternoon shadows grew long, but we refused to leave until we reached the lake, or what was left of it. We tromped down the hill toward the creek bed. The sky opened up in the clearing where the lake used to be. The plush, sun-dappled floodplain was dotted with lowland sycamores, patches of cattails shifted in the breeze. The shadows of turkey vultures and hawks crossed the swaying lake bottom like fish used to do.

What we found was probably more like what was here before the Ingram family. It was what the Muscogee-speaking people might have seen, and the clans before them—a clearing with a thin creek snaking through it. With the landfill now closed, there was a good chance the park’s time had come. What would it mean for the residents in the shadow of those landfills, with gentrification closing in?

When I got home later that night, still high from forest bathing, grainy ringlets plastered to my neck and perfumed with Deet, I found my husband reading in a corner armchair, the kids already in bed. I practically twirled in the door, wanting to tell him about this mysterious place. I tried to pull him away from his reading, suggesting that he come upstairs and check me for ticks. The forest can do that to you—remind you of your animal flesh, your short lifespan—even in the middle of Atlanta.

Within a couple years, Black Atlantans who were promised a park in the ’70s and fought the landfill in the ’90s will finally be able to walk past the chainlink fence, owners of a place that was off limits for generations. Their grandchildren’s inheritance is not just the land, but the chance to “lose themselves” in a carefully managed wilderness in a way that their parents never could. Soon, too, White families like mine that have never ventured to this corner of Atlanta will discover those woods on afternoon picnics, marveling at the beech trees and soapstone boulders.

Enshrined as a nature preserve, what will we name the place? Should we erase Charlotte Sage, ill-fated princess of Mount Manor Lake? Or honor Ted Mastroianni, Aaron Jackson Jr., or Herman Lischkoff—all of the figures whose fates entwined with the place and made it so difficult to bulldoze? Whatever we call it, I hope it will honor the countless Southside neighbors who organized to prevent Lake Charlotte from becoming a dumping ground. This is their victory and their park.

This article first appeared in the Built/Unbuilt Issue (vol. 27, no. 3: Fall 2021).

Hannah S. Palmer is author of the award-winning memoir Flight Path: A Search for Roots Beneath the World’s Busiest Airport. A native of Atlanta’s Southside, her writing about place is informed by her work as urban designer. Since 2017, she has led a campaign to restore the urban headwaters of Georgia’s Flint River.NOTES

- Fulton County GIS, Property Map Viewer, accessed April 13, 2021, https://gis.fultoncountyga.gov/Apps/PropertyMapViewer/; DeKalb County Parcel Viewer, accessed April 13, 2021, https://dekalbgis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=f241af753f414cdfa31c1fdef0924584.

- Eric Stirgus, “Landfill Foes Plan Monday Rally at Capitol,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 4, 2002; Kimberly H. Byrd, “‘Enough Is Enough,’ Landfill Foes Say,” Atlanta Constitution, January 28, 1999; David Pendered, “Battle Brewing over Landfill Proposal,” Atlanta Constitution, August 30, 1994.

- Hal Lamar, “Residents Rally against Live Oak Extension,” Atlanta Voice, November 15, 2003; Eric Stirgus, “Officials: Shut Landfill in ’04,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 13, 2003.

- “Metro Scenes: DeKalb. Indian Relics,” Atlanta Constitution, May 9, 1984; Stirgus, “Officials”; “Atlanta’s Live Oak Landfill to Become Source of Renewable Energy,” Renewable Energy World, September 21, 2007.

- Atlanta Bureau of Parks and Recreation, The 1975 Annual Report, Planning Atlanta Planning Publications Collection, Georgia State University Library, p. 1, https://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/digital/collection/planATLpubs/id/24207/rec/1.

- Barry King, “Atlanta Decides to Construct Own Campsites,” Atlanta Constitution, June 8, 1979; Jay Lawrence, “Atlanta Putting Emphasis on Open Space for Parks,” Atlanta Constitution, March 17, 1977.

- Atlanta Regional Commission, Areawide Outdoor Recreation Planning in the Atlanta Region: Proposed Nature Preserves, 1979, Planning Atlanta Planning Publications Collection, Georgia State University Library, https://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/digital/collection/planATLpubs/id/751/rec/2.

- Nehl Horton, “City Accepts Bid on Lake Charlotte Land, but Loses $145,756 with the Decision,” Atlanta Constitution, May 1, 1986.

- Brenda Mooney, “Slain Youngster Had Been Told to Be Careful,” Atlanta Constitution, November 4, 1980.

- Tony Cooper, “Lawyer’s Body Found in S.E. Atlanta Lake,” Atlanta Constitution, September 29, 1981; Charles Anderson, “Neighborhoods: NPU-T Oks Redevelopment Plan, Conditionally,” Atlanta Constitution, March 18, 1982.

- Nehl Horton, “Beverly Hills Residents Applaud Zoning Denial,” Atlanta Constitution, February 20, 1986.

- “Tree Canopy Atlanta,” Center for GIS at Georgia Tech, Trees Atlanta, 2015, http://geospatial.gatech.edu/TreesAtlanta/.

- “Atlanta 1927–30 Topographic Maps with Open Street Map Overlay,” Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, accessed April 13, 2021, http://disc.library.emory.edu/atlanta1928topo/.

- “Dr. R. F. Ingram, Candidate for Council from Second Ward,” Atlanta Georgian and News, September 21, 1908, Digital Library of Georgia, https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn89053728/1908-09-21/ed-1/seq-14/print/image_632x817_from_2144,81_to_4260,2813/.

- “Miss Charlotte Sage to Make Debut at Reception on Dec. 22,” Atlanta Constitution, September 27, 1936.

- “Mrs. Charlotte S. McKnight Dies; Funeral to be Today,” Atlanta Constitution, March 14, 1956.

- DeKalb County Planning Department, Soapstone Ridge: Its Environment and Land Use, June 1976, Planning Atlanta, Planning Publications Collection, Georgia State University Library, https://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/digital/collection/planATLpubs/id/34120/rec/23.