My grandmother keeps texting me poorly lit pictures of cake pans from her kitchen in North Texas. She’s decluttering, an undiagnosed symptom of late-age grief for a life that didn’t quite turn out as she hoped. Her cake baking tools are the first to go. My grandmother was a professional cake baker and, while it wasn’t a full-time job, the work helped put my grandfather through graduate school, feed and clothe four children, and keep the family firmly in a middle-class lifestyle for decades. She had clients across the state and some just across the Red River in Oklahoma. She made birthday cakes completely smothered in brightly hued buttercream, cakes for baptisms and other celebratory life moments, and giant, multi-tiered wedding cakes, delicately arranged with overpiping, molded chocolates, and anything a bride could dream up. I was in awe of her butter and sugar skills, naively believing my grandmother had figured out what so many women struggled to achieve as mothers and homemakers in the 1970s and ’80s. I thought the cakes bought her freedom.

When I visited during the summers, the peak of wedding season, I helped her haul bricks of unsalted butter from the grocery store, temper chocolate, and swaddle warm cake layers in plastic wrap. We stacked them in the second fridge she kept in the garage for her work. An industrial-sized steel stand mixer, almost as big as my grandmother, sat next to the fridge. When she mixed up buckets of buttercream for a wedding cake, I sometimes got to add a drop of blue food coloring to offset the yellow in the butter for the perfect bridal white. Cake scraps went into an old orange Tupperware she kept on the back counter for grandchildren to snack on. When it was time to deliver a cake, we’d pack the layers individually in the back of her car and carefully creep through town, avoiding turns and bumps at any cost. Later on, she bought a special magnetic sign she affixed to the bumper that read “Slow: Wedding Cake.” She stored the magnet on the front of her washer in the garage and beamed whenever she used it for a delivery. With a cake safely in its place, we’d return home to wash everything—the waxed fabric piping bags, the once-transparent chocolate molds, endless off-set spatulas, and more—all by hand. Her cake tools never went in the dishwasher.

While I was planning my own wedding a decade ago, my grandmother pulled out several large plastic three-ring-binders stuffed with pictures, notes, and wedding programs from cakes she created throughout her career as a baker. She planned to retire from the business soon and hoped to only bake cakes for family occasions. From the other room, I heard my grandfather grumble. Snippets of general disdain for cake, groans about the quantity of her baking equipment, and dramatic sighs about her work. Since I could remember, my grandfather approved of her homemade biscuits in the morning and the dinners she put on the table each night, but her cakes crossed over into complicated territory, one of women’s empowerment, agency, and financial independence via her entrepreneurship.

I now recognize this tension over my grandmother’s baking as my grandfather’s frustration with her ability to achieve for and by herself. My grandmother’s work linked her to a world of young brides, mothers, and a larger community of women who deeply respected her craft and recognized its worth. The cakes provided her with a professional network of bakers and special event creators who further spread word of her skills. Baking cakes professionally allowed her to create another identity outside of wife and mother. Since the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, and with the rise of both women’s and food studies, scholars have examined women’s economic and creative activity and recognized the significance of their cultural production, including food-related labor like baking. Today, as I follow in those scholars’ footsteps, I connect my grandmother’s baking with my research on the cultural capital of cakes, including my own baking.

I find it particularly frustrating that the most ornate and involved technique for frosting a cake is named after a man. Popularized in the 1930s by a British baker named Joseph Lambeth, the method, also known as overpiping, involves the delicate layering of frosting to create intricate—some would even say feminine—designs. Akin to lace or ruffles you might find on the edges and hems of fine garments of old, overpiping creates dainty knit-like swoops, swirls, and fine-lines. Lambeth published The Lambeth Method of Cake Decorating and Practical Pastries in 1934, and the Lambeth name stuck despite being common practice for generations of bakers before him. And while Lambeth never claimed to have invented overpiping, the fact remains that his name is attached to it. Though he was a talented baker who wanted to share his skill with the world, it is hard for me to separate him from his role in the legacy of systemic discrimination I’ve inherited from women bakers before me, my grandmother chief among them. Men and women have baked equally spectacular cakes throughout history, but women were seen as hobbyists, homemakers, and enthusiasts. Men mastered the craft. Women baked cakes.

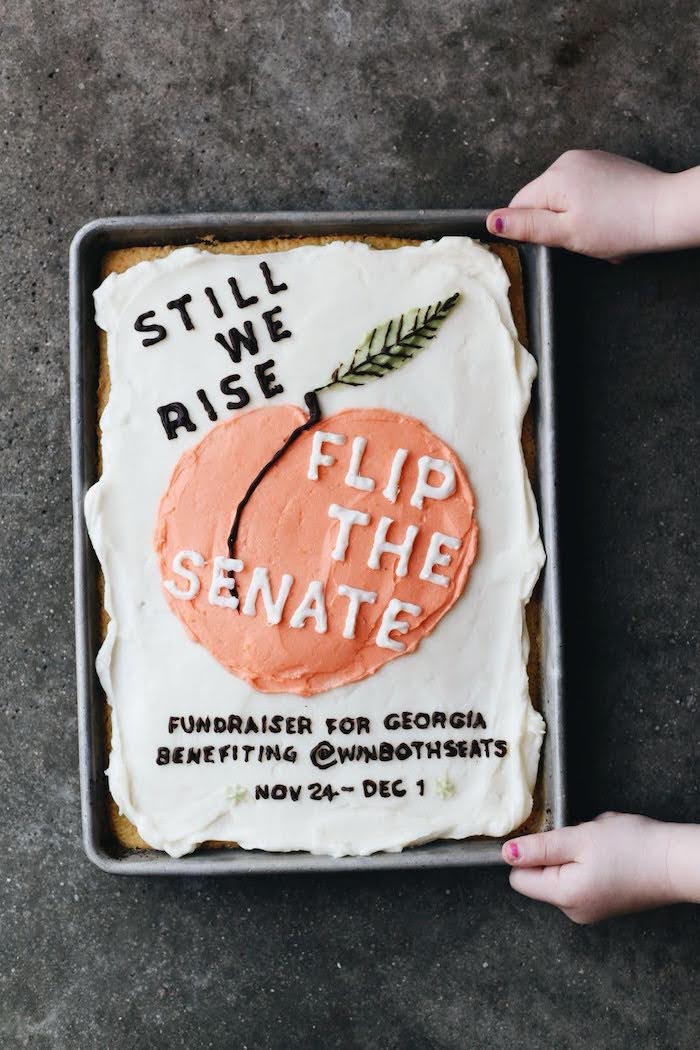

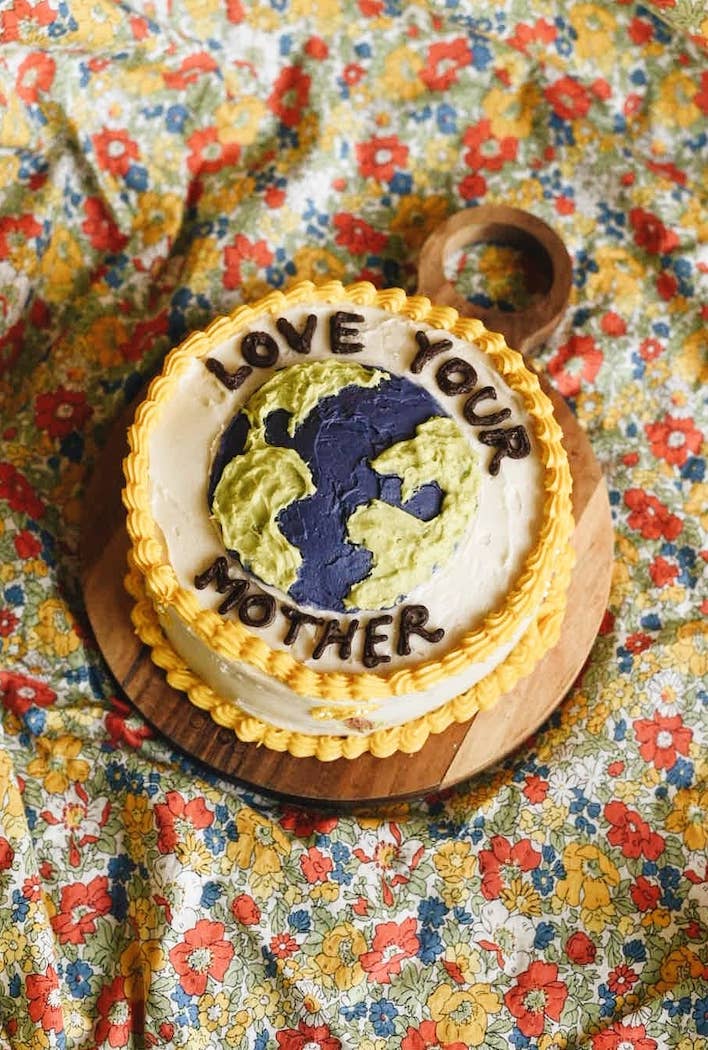

For the past few years, buttercream closeups and contemporary takes on the Lambeth method have monopolized my Instagram feed. Highly decorated cakes never really disappeared; even the minimally frosted naked-cake craze of the early aughts, partially popularized by celebrity chef Christina Tosi of Momofuku Milk Bar, carried its own context about frugality, minimalism, and the gendered expectation that women inherently possess sweet demeanors. Wedding cakes in particular are telling expressions of society at a particular moment, the thickness of the frosting and the number of layers waxing or waning with inflation, the maker’s time and skill, and politics. Overpiping returned in full force in 2017, a year after the highly conservative federal administration threatened access to women’s healthcare, caged immigrants sought asylum, and legislators sympathized with white nationalists and the preservation of Confederate statues. I watched Tina Fey, a University of Virginia alumna, on Saturday Night Live as she shoved forkfuls of prettily frosted store-bought sheet cake into her mouth, calling it “sheetcaking,” a new form of “grassroots movement.” Instead of participating in the political violence or the increasingly hostile rhetoric sweeping the nation, Fey stifled her screams with cake. Feminist scholars, the media, and even Fey herself critiqued the skit, equating it to Marie Antoinette’s wrongly remembered phrase “let them eat cake”— another example of white women’s privilege and our historic tendency to look the other way. The baking community interpreted her skit differently, shocked and slightly offended over the idea of using cake as a desperate escape from reality and instead seeing it as an opportunity to demonstrate the cultural power cake has always possessed. Cake wasn’t Fey’s usual medium and her joke failed. But bakers know how to communicate the symbolic power of buttercream.1

Social media’s community-building possibilities mean we are able to make decent money from these cakes, as well. Depending on how the cottage industry laws work in a specific state, bakers sell slices of their cakes along with other baked goods through digital pop-ups on Instagram, raffle whole cakes to their social media followers for causes ranging from natural disaster relief to emergency funds for Ukrainian mothers and children. They market virtual classes of their decorating methods. Some bakers monetize their social media feeds, through sponsorship or in-app creator funds, and some secure cookbook and other media deals based on their cake baking abilities. We use our skills, passed down matrilineally, by observing collaborators in cookbooks published by cake supply companies like Wilton, studying magazine articles and cooking shows, including the great cake diva Martha Stewart, and on social media. We don’t intend to hoard what we have learned. It is certainly not “just cake.” There is a message.2

Historian Ann Romines argues that cake can serve as a method of communication, or rather, an extension of the “limits of written language” in women’s literature. One powerful example is Eudora Welty’s 1946 domestic drama Delta Wedding and its many emblematic baked goods. But I see these cakes every day on my phone. Scrolling through social media, a liminal space somewhere between reality and fiction, women routinely post images and recipes for cakes not unlike those demonstrated in Lambeth’s manual. With their multihued overpiping, delicately placed sugar pearls, and increasingly socio-political messages inscribed in buttercream, these cakes are the digital descendants of a long line of women’s shared domestic labor. Romines notes that the change from oracular tradition (word-of-mouth) to written and printed methods “raised important questions about the implications of going public with women’s traditional domestic culture.” The nineteenth century publication of women-authored cookbooks blurred lines between the “separate spheres” that presumably kept women and their domestic knowledge isolated, even invisible. Today, women chefs, cookbook authors, editors, journalists, food photographers, and stylists are proof of the fluidity of gendered spaces. But these twenty-first-century cakes tell a different story, requiring, in Romines’ words, a rereading for the digital age.3

Much like reading cakes in literature or contextualizing recipes in cookbooks, women’s digital food media similarly provides opportunities for critical analysis. In the digital landscape, however, the messages within cakes are no longer hidden from plain sight. Women creators are using textual features like captions and more subversive details delicately buried in a post (like a shredded root vegetable in an otherwise sugary cake) and outside the viewer’s immediate focus, such as metadata in handles, hashtags, and user metrics. In the past, shared domestic culture sustained personal, familial, and communal networks; the introduction of the digital has reinforced these associations and created new opportunities for women to use feminist interventions in such a food landscape.

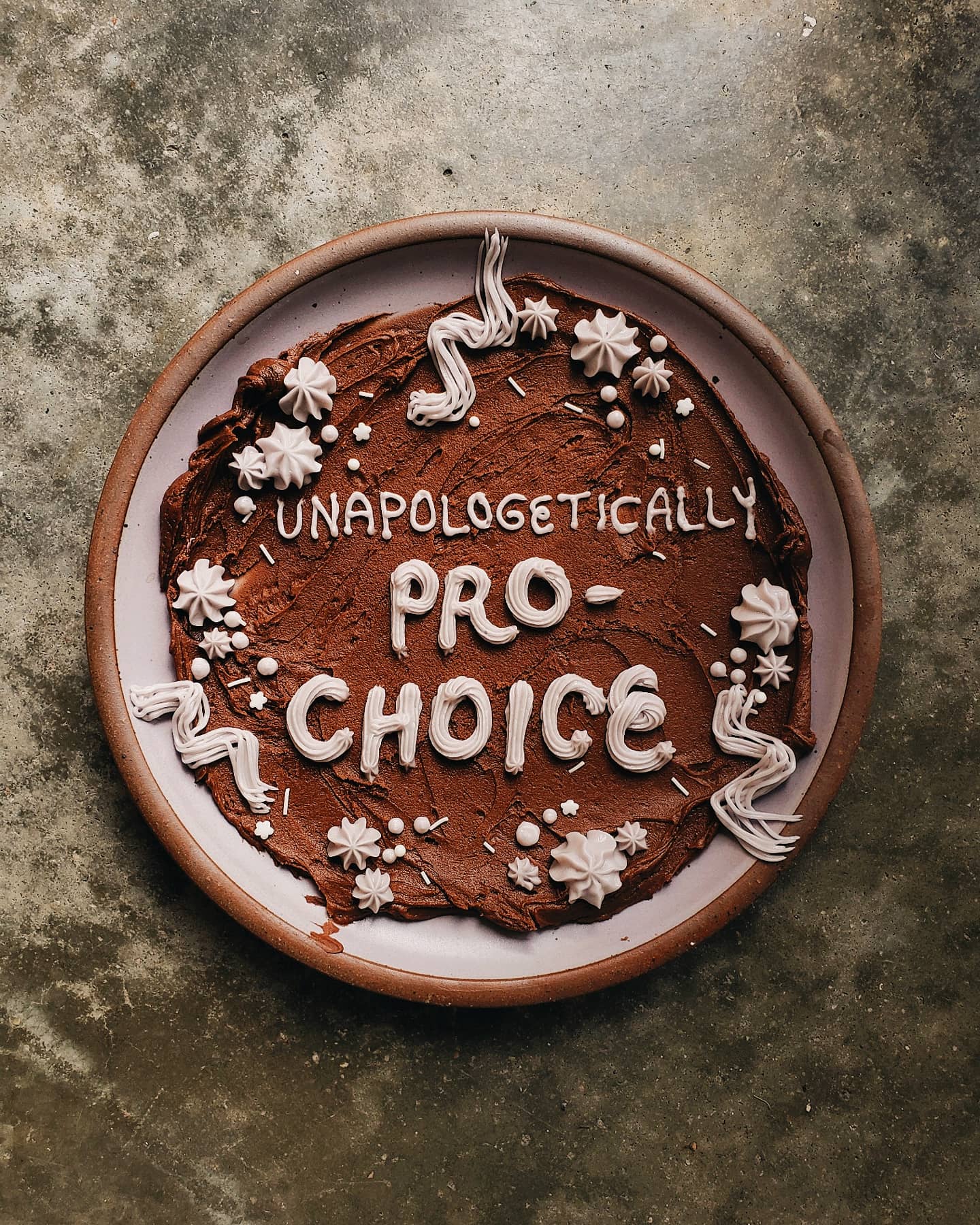

Digital cakes play a pivotal role in the American South, where systemic oppression continues to push women into unsafe and compromised situations. In the spring of 2019, after a slew of states passed “Fetal Heartbeat” bills banning abortions after six-weeks, women took to social media to protest the new laws. Austin, Texas–based Becca Rea-Tucker, who goes by the handle @thesweetfeminist on Instagram (where she has 245k followers), expressed her thoughts in layers of cake, buttercream, and sprinkles. One cake reads “abortion isn’t a bad word” piped in purple cursive frosting. Another says “ABORTION IS HEALTHCARE” in pink bordered by a circle of matching pink piped buttercream peaks and multicolored nonpareils. As the bans continued and new laws passed in Georgia, Missouri, Texas, Alabama, so did the online protests. Reflecting the growing seriousness of the restrictive legislation, Rea-Tucker’s cakes became less decorated and more to the point. One post shows a plainly frosted white cake with purple frosting letters: “you don’t have to justify your abortion to anyone.” Another cake, with a frantic swirl of pink and blue frosting, reads, “RAGE IS A RATIONAL REACTION.” That rage, however, was not limited to the people who opposed the abortion bans. Rea-Tucker, who has a cookbook coming out in the fall, received criticism, and even death threats, about using her feed and cakes as a political platform. Her response to the pushback was yet another cake decorated with multicolored sprinkles and buttercream cursive which read, “it’s not ‘just a cake.’”4

Over in Athens, Georgia, self-styled “hobby baker” Trinity Andrew (@trinityskitchen) uses her baked goods to speak about social justice issues from police violence to affordable housing and Indigenous land rights. On July 4, 2021, Andrew posted a cake featuring a delicate star-piped border with a scenic pastel mountain view applied in a newer frosting style Instagram bakers call buttercream painting. The method uses small offset spatulas, also known as palette knives, borrowed from oil painter’s toolkits). Above the pale purple mountains majesty is the simple phrase “LAND BACK” in black frosting. In Richmond, Virginia, Arley Arrington, who goes by @arley.cakes on Instagram, includes both the words “baker” and “rebel” in her bio. Arrington uses her baking to speak on a number of issues, but the majority of her cakes focus on the systemic racism experienced by Black Americans. Her most recent post is a sheet cake styled in the design of Kristen Green’s recently published The Devil’s Half Acre: The Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated the South’s Most Notorious Slave Jail. The book, and Arrington’s cake, centers on Mary Lumpkin, a formerly enslaved woman who was raped by her enslaver. She later transformed a jail that held enslaved Black people into an HBCU. Arrington painted Lumpkin’s silhouette with black-tinted frosting to match the book cover. Arrington’s cake book cover conveys the power of buttercream.

While digital realms present new and exciting opportunities for women to gain agency, financial independence, and empowerment, they also present numerous obstacles that ultimately contribute to women’s systemic and systematic disenfranchisement. The digital world offers flexible employment for mothers who must navigate difficult childcare schedules. More recently, professional women bakers and pastry chefs laid off and furloughed during the global pandemic turned to social media to showcase and monetize their skills through bake sales and pop-up cake sales. Building a business on a rapidly changing and fickle digital platform takes significant time, effort, and virtual expertise. Knowing that these obstacles exist, why would women want to digitize their domestic expertise? What is there to gain? And what is the impact of using this expertise in “radical” resistant ways? Thinking about how Instagram is both part and influencer of American life, feminist literary scholar Jane Marcus suggests that women’s culture adheres to an aesthetic that does not wish to compete, is anti-hierarchical, anti-theoretical, not aggressively exclusionary. A real woman’s poetics is a poetics of commitment, not a poetics of abandonment. Above all, it does not separate art from work and daily life.5

The “women’s culture” Marcus describes centers on products that are used or consumed and occupy space temporarily due to their perishable nature. To be clear, this interpretation does not devalue women’s contributions; rather, it underlines the importance of celebrating the domestic and the everyday, the “food that is eaten,” the “cloth that is worn,” and the “houses that are dirtied.” Romines uses Marcus’s claim that “culture consists in passing on the technique of its making” to explain how culture “consists in recipes.” But what if that recipe does not follow traditional cookbook methods, but instructs the user in techniques for resisting oppression?6

I didn’t explain to my grandmother why I wanted the back issues of her beloved Wilton Cake Decorating Yearbooks in the winter of 2020. As much as she always supported my career and academic endeavors, I knew she was thankful that the past year gave me more time to be with my children and to “mother.” Her collection dates back to the 1970s, but I wanted the issue from 1989, the year I was born—over a decade after the first official International Women’s Year in 1975 and well into the era of “women can have it all.” I needed this issue for a buttercream-message topped layer cake I planned for International Women’s Day in March 2021. My contemporary version of the cake featured the same buttercream elements, including piped chocolate lines overlapped to resemble a grapevine wreath, dainty dusky blue flowers, and a pale ’90s pink ribbon, as well as iconic white chocolate Country Goose geese adorned with little blue bows (just like my mom and countless other moms had in their 1990s kitchens). The inspirational cake featured on the 1989 cover read “Welcome Friends.” With room to spare on my own cake top, I piped a few more so the message read: “Welcome to the Eighties, Ladies.”

The day marked the first anniversary of the start of the global pandemic, the shutdown of childcare and schools, and the catastrophic setbacks for women that followed. We pivoted from “having it all” to “doing it all.” In less than a year, as employment rates plummeted to numbers not seen since the late 1980s, reports of domestic abuse and restrictions on women’s access to healthcare resources steadily rose. Readable cakes exploded on social media and, as evidenced through the drastic approval of cottage industry laws across the nation starting in 2020, women who had lost their brick-and-mortar baking jobs or pivoted to baking from home as a new source of financial revenue increased. In December 2020, a woman-owned, Austin, Texas based brand called Pretty Shitty Cakes sidestepped the legal concerns entirely by making retro-piped cakes out of cardboard, paint, and piping bags filled with colored spackle and fitted with real piping tips. Owner Jasmine Archie typically finishes her bakes with brazen color combinations and one-too-many layers of “frosting,” as well as a smattering of impudent phrases such as “sexy,” “fuck,” and “chill the hell out.” While Archie’s cakes are designed to be traditionally dainty (though purposefully irreverent) decorations, they also serve as enduring examples of how women use cake (even inedible versions) as a form of communication.7

Rather than an act of celebration, my Women’s Day cake was a creative call-to-action spelled out in buttercream—a call that rang out far beyond my kitchen and joined together with women throughout the nation, especially here in the South. Thanks to my grandmother’s mentorship and my careful practice with the piping bag, there was no misreading it.

KC Hysmith is a Texas-bred, North Carolina-based writer, food historian, recipe developer, and photographer. Her research sits at the intersection between food, gender, and the digital landscape. Her writing and work have appeared in Gastronomica, The Boston Globe, Kitchn, Indyweek, The Local Palate, and more. She is currently a PhD Candidate in American Studies at the University of North Carolina.NOTES

- Melissa Locker, “Tina Fey Destroys a Sheet Cake in the Name of Self Care,” Food & Wine, August 18, 2017, https://www.foodandwine.com/news/tina-fey-destroys-sheet-cake-in-name-self-care; Rose Dommu, “Why Tina Fey’s ‘Sheet-Caking’ is the Epitome of White Privilege,” Out, August 19, 2017, https://www.out.com/news-opinion/2017/8/19/why-tina-feys-sheet-caking-epitome-white-privilege.

- Mentioned later in this essay, Becca Rea-Tucker, aka @thesweetfeminist, has a cookbook (published by Harper Wave) coming out in October 2022.

- Ann Romines, “Reading the Cakes: Delta Wedding and the Texts of Southern Women’s Culture,” Mississippi Quarterly 50, no. 4 (Fall 1997): 601; Romines, 602; Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820–1860,” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (Summer 1966): 151–174.

- Becca Rea-Tucker, @thesweetfeminist, Instagram, May 9, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/BxPox3QBehU/; Rea-Tucker, @thesweetfeminist Instagram, May 15, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bxe7IjohY1X/; Mara Gordon and Alyson Hurt, “Early Abortion Bans: Which States Have Passed Them?” NPR, June 5, 2019, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/05/729753903/early-abortion-bans-which-states-have-passed-them; Rea-Tucker, @thesweetfeminist, Instagram, May 16, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/BxhrOAYhcV_/; Rea-Tucker, @thesweetfeminist, Instagram, May 17, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/Bxkk0NJB7_p/; Rea-Tucker, @thesweetfeminist, Instagram, June 10, 2019, https://www.instagram.com/p/ByjLYWdBW_q/.

- Jane Marcus, “Still Practice, A/Wrested Alphabet: Toward a Feminist Aesthetic,” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 3, no. 1/2, Feminist Issues in Literary Scholarship (Spring–Autumn, 1984): 79–97.

- Romines, “Reading the Cakes.”

- “A Year of Strength and Loss: The Pandemic, the Economy, and the Value of Women’s Work,” National Women’s Law Center, March 2021, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Final_NWLC_Press_CovidStats.pdf; “The Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women During Covid-19,” UN Women, https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19; Southern states with relatively new Cottage Food laws, many which feature incredibly important higher revenue caps, include Washington DC (March 2020), Mississippi (June 2020), Arkansas (April 2021), Alabama (May 2021), and Florida (June 2021). “Recent State Reforms for Homemade Food Businesses,” Institute for Justice, https://ij.org/legislative-advocacy/state-reforms-for-cottage-food-and-food-freedom-laws; Bettina Makalintal, “For a Sugar Rush That Lasts Forever, Get a Fake Cake,” Munchies, April 1, 2021, https://www.vice.com/en/article/wx8wd4/instagram-retro-inspired-fake-cake-decor-trend; Pretty Shitty Cakes, @prettyshittycakes, Instagram, February 2, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CZfAS87OQkW/.