We cannot understand the power and the meaning of food until we understand hunger. Hunger at its most basic is the lack of food, and therefore a body’s need and craving for food. If we are very lucky in this world, we feel hunger as a minor physical discomfort that can be readily sated: a sandwich to go, a bag of chips from a vending machine, a cup of soup in the microwave.

Hunger, of course, can also mean a craving for something that food represents or promises but somehow has failed to deliver to us.

The ritual of sitting down to a meal, is this not the theater of community and family? Eating a dish prepared by someone who cares for you and your well-being, is this not the tangible representation of love and caring? Then, there’s the intake of flavors, vivid and deep, nurtured by the sunlight above and the earth beneath our feet, is this not the epitome of a sense of place and the pleasure of belonging?

It’s this latter form of hunger—the hunger of the spirit more so than the body, though they are often intertwined—that my novels and essays fixate on.

As a writer, I’m interested in food and eating as performance, ritual, replacement, reward, punishment, pleasure, resistance, and as means of creativity and communication. Basically, everything but the food itself. If I write about a tree-ripened plum, its purple skin split by the sun, I don’t do so in order to make the reader desire the plum itself, but for what that plum represents within the narrative and the text. In life, I desire the plum too. In literature, the plum is a bit more complicated than that.

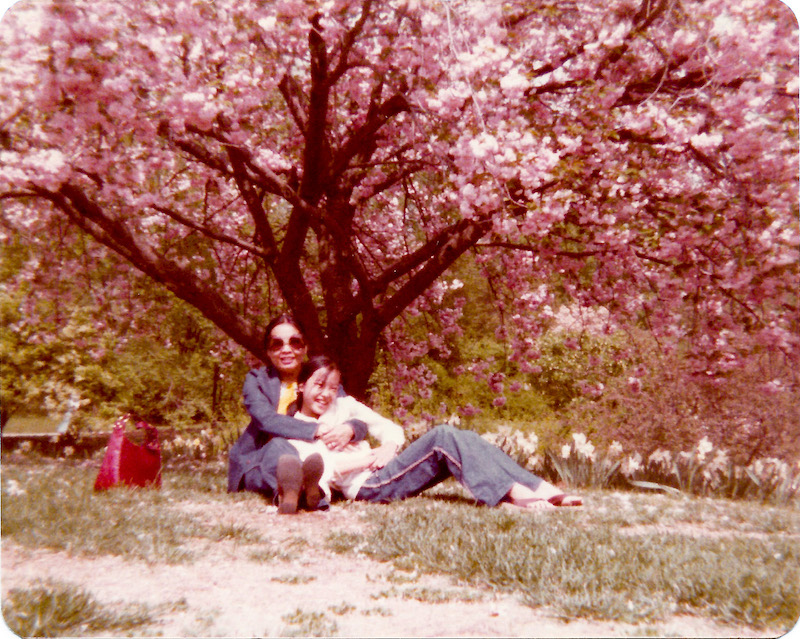

My novels are often described as being rich in food. But they are also rich in hunger. In 2003, after my first novel The Book of Salt was published, I was asked by the pen/Faulkner Foundation in Washington, D.C., to write a response to Eudora Welty’s collection of autobiographical essays entitled One Writer’s Beginnings. As Welty had done so eloquently, I was tasked with tracing my memories back to a moment when writing, which for me means writing larded with hunger, became a necessity. I found myself back in San Diego County, California, at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, which in April of 1975 was a relocation camp for Vietnamese refugees, and what I found there was a ridiculously symbolic “first” meal in the United States of America—hamburger and fries—and a note, penned by my mother, that helped us procure this sustenance that otherwise would have been out of reach. Written in English, the note contained words that I couldn’t yet read but would continue to feed me. It was a memory so submerged that I had to telephone my mother to make sure that I had not made it all up.

Rooted in a moment of forced migration that altered and shaped my perspective on food and my imaginative relationship to it as well, that meal and note explained why my belly and my brain have had such a decidedly codependent relationship; why food and words are my conjoined obsession.

All those thousands of refugees, standing in long lines, hour after hour for their own first meals, were in shock, in grief, and unmoored, but the one thing that they probably were not was physically hungry, especially considering the food at Camp Pendleton.

Yet, food there was the obsession, the sole focus and task of the long days of otherwise not knowing what would come next. Instead of seeking the larger, overwhelming, unimaginable answers, we refugees focused on which truck had the fresher fruits, which one had chicken, which one was trying to serve us something called “egg foo young,” a dish that we certainly did not recognize and that everyone called mửa, or throw-up.

When we left Camp Pendleton, my family came to Boiling Springs, North Carolina, and for the next three years we would call this little town in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains our home.

I often tell people that I’m a southern girl twice over, meaning that I was born in South Vietnam and that I was reborn in the American South with a new name and a new language. Of course, only one of these places is written on my body. Only one of these places defines me in the eyes of most who see me. The American South is my secret. My relationship to this region, known for its gracious, effusive “southern hospitality,” and in 1975 also for its recalcitrant racism, is a complicated one. During my childhood in Boiling Springs, I was the beneficiary and the target of both.

Boiling Springs and nearby Shelby are the settings of my second novel, Bitter in the Mouth. By locating my novel there, I could revisit, unpack, and reclaim this state that was my first American home. The novel’s main character, Linda Hammerick, has synesthesia, a neurological condition that causes words, either spoken or heard, to be accompanied by phantom flavors, most of them lifted from a southern table. For Linda, the word “later,” for instance, brings with it the richness and tang of pimento cheese, “fiduciary” a sweet pull of Cheerwine, the bright red, cherry-flavored cola produced in Salisbury, North Carolina, and the word “character” serves forth pickled watermelon rind with its equal parts vinegar and sugar and a linger of cloves.

It’s a secret sense that Linda can and does keep from those around her. It forces her, however, to learn at a tender age that, in order to fit into the world, she would need to ignore, suppress, and even manipulate all that is strange and unusual, even when that is her very own body. In Bitter in the Mouth, I renamed myself Linda Hammerick. I imagined a different family, a different childhood, and a different relationship to the sense of taste—the sense that I enjoy the most; but in the end it remains a story about claiming a home in another South.

Bitter in the Mouth is my re-imagining of a Southern Gothic novel. One of the hallmarks of a Southern Gothic novel is the family or community secret, submerged or kept barely below the surface. The secret is often a person, hidden away or for some other reasons not seen, with a purported, rumored, or actual deformity or difference. In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, the secret person is Boo Radley; in Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms, it’s cousin Randolph’s transvestite alter persona; in William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, it’s Benji. Bitter in the Mouth belongs to this tradition, but it poses the following questions: What if the narrator herself is the family secret? How would she “reveal” herself to the reader and how would that unmasking change her story for the reader?

Bitter in the Mouth is a novel that plays with the idea of the unreliable reader. The first half of the novel is constructed as an invitation to the reader to fill in the blanks. For example, when we meet Linda, her sense of otherness and difference, as defined by her, is her “secret sense,” i.e., her synesthesia.

We also learn about her family. Based on their first and last names, their North Carolina locale, and their physical descriptions—the grandmother’s milky blue eyes, the mother’s blond hair, the great-uncle Harper’s white hands—there’s a reasonable, though not accurate, assumption that Linda is in these ways like her family: white and southern.

How do we as readers “fill in the blanks” when we are told only part of the story? I think we do it by drawing upon all the other stories, fact or fiction, that we already know, in order to find analogous circumstances, transferable scenarios, and probable outcomes.

We are told stories, throughout the course of our lives and especially when we are children, in order to teach us a lesson or a set of social norms. This is why Linda, in retelling her childhood in the first half of the novel, combs through the stories of her youth—fairy tales, Greek myths, North Carolina history and legend—to do just that: to try to fill in the blanks of her own story.

Linda tells us that when she was eight years old, her father gave her a book entitled North Carolina Parade: Stories of History and People, which was a book that my own father gave me when I was eight years old. I still have my copy. Like Linda, I’ve taken North Carolina with me to all the places I’ve lived since leaving Boiling Springs. Linda revisits, reinterprets, and embellishes the figures she first met on the pages of this childhood gift: Virginia Dare, Chapel Hill’s George Moses Horton, and the Wright Brothers—young Ohioans who made history on the shores of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

In Virginia Dare’s story, Linda recognizes another orphan on the shores of North Carolina; in the poet George Moses Horton’s, she finds another North Carolinian with a transformative and, at first, a necessarily secretive relationship with words; and in the Wright Brothers’s story, she witnesses a desire to be freed from the land, the same land that she desires most to be tethered to.

At the heart of Linda’s reframing of the Virginia Dare legend, which is intertwined with her own story of how she became separated from her father and mother, there’s a deep longing that we both share as young newcomers to North Carolina. We hunger for a moment when our physical bodies and our internal narratives are not bifurcated, disjointed, and out of sync with ourselves or with our surroundings. We crave a sense of wholeness, the rarest of the senses.

This essay appeared in the “Inside/Outside” Issue (vol. 25, no. 2: Summer 2019).

Born in the former Saigon, South Vietnam, MONIQUE TRUONG came to the U.S. as a refugee in 1975. Her novels are The Sweetest Fruits (Viking, 2019), Bitter in the Mouth (Random House, 2010), and The Book of Salt (Houghton Mifflin, 2003). She is also an essayist and a librettist. monique-truong.com.

Header image: Menges party, 1977, Livingston Manor, New York, by John Margolies, courtesy of the Library of Congress.