“In Atlanta, nothing else seemed to matter with the champ in town. He owned the city. It was a powerful scene—’sheer Black, street-corner ebullience out for a Sunday evening promenade.”

The wait was over. On October 25, 1970, on the eve of Muhammad Ali’s first professional boxing match in forty-three months, African Americans flooded the streets of Atlanta, anxiously anticipating what Ali called his “day of judgment.” They came from all over: Birmingham, Chicago, Detroit, Harlem, Miami, and Philadelphia. Peachtree Street had never been more colorful. Rows of chrome covered cars, gold limos, and purple Cadillacs lined the road. One fan, a slender man smoking a foot-long pipe, wore an ankle-length mink coat matched with a tall mink hat. Another man who washed dishes for a living told a reporter that he had saved for months so he could buy a puce suit and bet one thousand dollars on Ali. Women dressed up like it was New Year’s Eve, sporting bouffant Afros, fake eyelashes, and sleek sequined mini skirts. The fight attracted a wide assortment of people, politicians and celebrities, hustlers and gangsters. The biggest names in Black America were in town: Bill Cosby, Sidney Poitier, Hank Aaron, Harry Belafonte, Curtis Mayfield, Diana Ross, Coretta Scott King, Whitney Young, Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, and Julian Bond. It was, Sports Illustrated observed, “the most startling assembly of Black power and Black money ever displayed.”1

That evening, Ali strutted down Atlanta’s thoroughfare with a loud, laughing entourage following closely behind. Black fans shouted his name as he passed the corner newsstands, clubs, hotels, theaters, and restaurants. Crowds swarmed him. In Atlanta, nothing else seemed to matter with the champ in town. He owned the city. It was a powerful scene, playwright Jack Richardson wrote, “sheer Black, street-corner ebullience out for a Sunday evening promenade. When Ali’s fans spilled out onto the streets of Atlanta one knew that there was a new tempo in town that was much more devastating to Old South rhythms than the gospel cadence of a freedom march.”2

His fans last saw him in the ring on March 22, 1967, when he knocked out Zora Folley in the seventh round at Madison Square Garden. About a month later in Houston, as the war in Vietnam intensified and draft calls escalated, Ali refused induction into the United States Army on religious grounds, claiming that he objected to wars not declared by Allah. Many Americans already despised him for his membership in the Nation of Islam, a separatist Muslim sect framed by the mainstream media as a subversive cult. Excoriated as an insincere, unpatriotic draft-dodger, Ali polarized the country. Immediately after he refused induction—before he had even been charged with a crime—the New York State Athletic Commission (NYSAC) suspended his boxing license and withdrew his heavyweight championship title for conduct “detrimental to the best interests of boxing.” Athletic commissions across the country followed New York’s example, leading critics to predict the slow death of boxing. On June 20, 1967, a federal court convicted him of draft evasion and sentenced him to the maximum five-year imprisonment and $10,000 fine. For the next three and a half years, free while his case worked its way through the courts’ appeals process, Ali waited to learn his fate.3

Never before was his widespread support in the Black community more evident than when he returned to boxing in Atlanta, a rapidly changing metropolis and the “Black Mecca” of the postwar New South. During the civil rights era, white moderates and Black elites envisioned a harmonious city, proudly proclaiming Atlanta as the “City Too Busy to Hate.” Atlanta’s culture of racial moderation and the influence of Leroy Johnson, a Black state senator who wielded significant political power, made Ali’s return to boxing possible. For over three years, promoters and politicians in dozens of cities had failed to arrange an Ali match, but Johnson leveraged his unique connections with Black and white municipal politicians to secure a boxing license for the former champ. “We are,” Johnson said, “showing the world that Atlanta is the capital of democracy.”4

“The eyes of the world,” Ali announced before the fight, “are on Atlanta, Geeeeeeeeeorrrrrgia.” More than twenty-five years before the city hosted the Olympic Games, Atlanta’s politicians and promoters transformed Ali’s popularity into an international sports spectacle, ushering boxing into a new global age. Hundreds of writers from all over the globe—Asia, Africa, Europe, and South America—traveled to Atlanta to see if Ali could still fight with the same speed, the same power, and the same élan that made him the “King of the World” in the 1960s. His match against Quarry attracted more than 100 million television viewers throughout the world, the largest boxing audience in history. For the first time, the Soviet Union, America’s Cold War enemy, broadcast an American fight via live satellite relay. Not since Joe Louis fought German Max Schmeling in 1938 had so many people around the world invested so much in one boxing match.5

The international interest in Ali’s comeback held important social and political implications for Atlanta. Julian Bond recalled that he had never seen so many Black Atlantans as excited about anything else in the city’s history. Bond, a young, handsome man, came of age in Atlanta during the 1960s. As a student at Morehouse College, he became a political organizer, an active leader of the sit-in movement, and a prominent member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1966, he was elected to the Georgia Legislature, but before he took his seat in the state’s gold-domed capitol, his colleagues refused to admit him because he had supported a SNCC antiwar statement. About a month later, when Ali became eligible for the draft, the champ quipped, “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong!” When Ali spoke out against the war, risking his title, career, and millions of dollars, Bond admired him. He believed that the government persecuted Ali because of his religious and racial views. So when the Georgia Legislature refused to seat him, Bond drew strength from Ali. “When Ali said he had no quarrel against the Vietcong, I was ecstatic. Suddenly, I didn’t feel so alone,” he said.6

For Bond and millions of African Americans, the Ali–Quarry fight transcended sports. Ali’s return to boxing marked a turning point in Atlanta history, symbolizing the culmination of civil rights activism, the destruction of old barriers, and the triumph of Black political power. As an international sports spectacle, the fight promoted Atlanta’s image as the exceptional city of the American South—a city too busy to hate Muhammad Ali. Looking back Bond observed, “It was more than a fight, and it was an important moment for Atlanta, because that night, Atlanta came into its own as the Black political capital of America.”7

“We Got Ali”

Watch Julian Bond’s recollection of the fight

The fight promoted Atlanta’s image as the exceptional city of the American South—a city too busy to hate Muhammad Ali.

The People’s Champ was nearly broke. In early 1969, during a paid television interview on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, Ali told Howard Cossell that he would return to boxing because he needed money. Facing mounting legal bills and a growing family, he searched for ways to earn a living outside of boxing. His greatest source of income came from delivering lectures at over two hundred college campuses, earning $1,000 to $3,000 for a single speech. He spent hours preparing, reading the latest newspaper reports from Vietnam, writing on stacks of white index cards, and rehearsing in front of a full-length mirror. For him, it was a time of education, a political journey that led him to examine race, war, and religion. Speaking in packed auditoriums, his voice rising to a singsong cadence, he recited his favorite poems, echoed the separatist rhetoric of the Nation of Islam, and sounded off against the war.

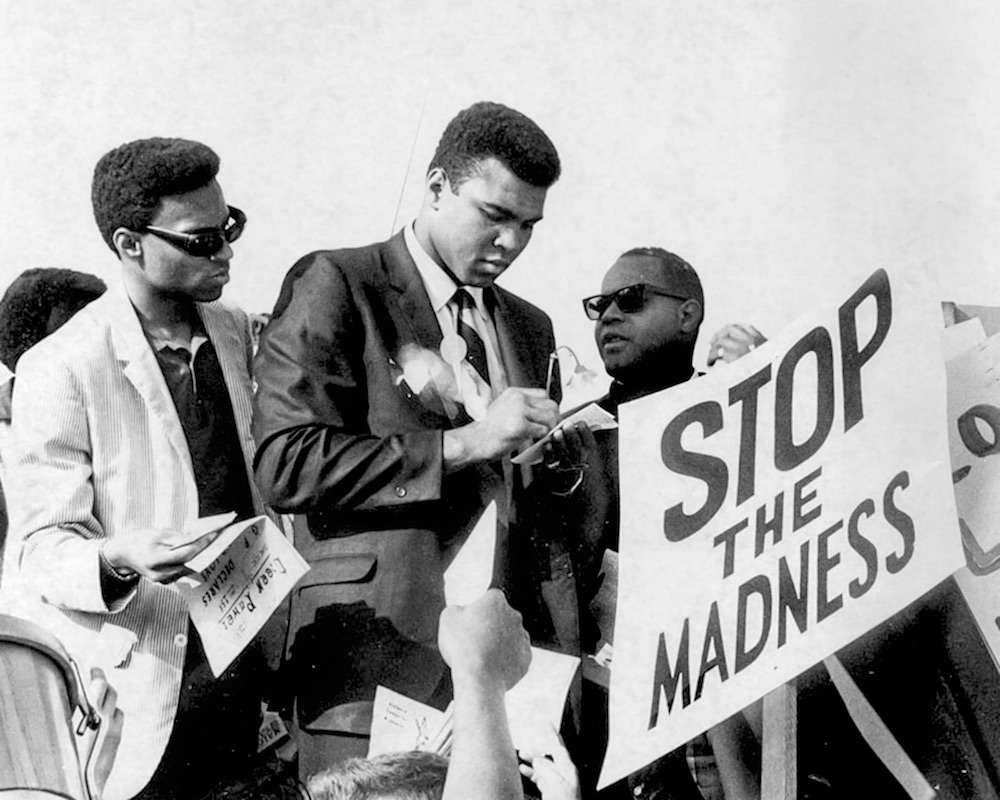

While Ali crisscrossed the country, he became an agent of social change, challenging young people to question the war, racial inequality, and the meaning of democracy in America. At the height of his lecture circuit, many Americans’ views about the war shifted toward peace. Disillusioned and angered by the mounting death toll in Southeast Asia, on October 15, 1969, more than two million Americans—ordinary citizens, clergymen, businessmen, writers, entertainers, schoolteachers, and congressmen—turned out for the national Vietnam Moratorium. A month later, public opinion polls showed that a majority of Americans opposed the war. As American attitudes toward the Vietnam War changed, so too did peoples’ opinion of Ali, increasing the likelihood of his return to the ring.

In exile, Ali demonstrated to the world that he was sincere in his stand against the war. After he was convicted of draft evasion, he became increasingly aware of how the politics of the war changed his life and affected Black people—his people. In his denunciation of the war and demands for racial justice, he became the “people’s champion” and a symbol of anti-American defiance across the globe. He asked, “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?”8

While Ali spoke out against the war, maintaining a hectic lecture schedule, he still struggled to pay his bills and sought additional sources of income. He made numerous appearances on national television shows, performed in an unremarkable Broadway musical, Buck White, and starred in a biographical documentary entitled A/K/A Cassius Clay. He even became involved with a chain of hamburger restaurants called “Champburger.” In early 1970, Ali cut a deal with Random House that paid him a $200,000 advance for his autobiography, The Greatest.

His newfound financial success led him to announce that he was retiring from boxing. “I know I won’t fight again,” he declared in the May 1970 issue of Esquire. Claiming that he was no longer a boxer, he announced that he had become a “Freedom Fighter” for Black people. Dealing with the press, the photographers, and the crowds, he said, was too much. But the truth was that he missed the world of boxing. Ali could continue to give speeches, but he was not an orator. He could perform on Broadway and make movies, but he was not an actor. He could open up more hamburger chains, but he was not a businessman. He was a boxer, and the ring was in his blood.9

He had not fought a professional boxing match in over three years and there was not a single state boxing commission that would grant him a license. Fearing a public backlash, governors calculated that there was no political benefit in allowing a match that would make an unpatriotic draft-dodger wealthy. No one understood the challenges of getting Ali a boxing license better than New York publicist Harold Conrad. A former sportswriter and screenwriter who knew everyone in the fight game, Conrad spent three frustrating years trying to secure a contract in twenty-two different states. He even proposed matches in Japan, Canada, and Mexico, but the Justice Department refused to let Ali leave the country.

Conrad had all but given up on promoting another Ali fight. He had tried just about everything to help resurrect Ali’s boxing career, but the former champion was too polarizing in a country fragmented by race and war. “Politics is what kept him out of boxing,” Conrad said, “and in the end, it was politics that got him back. And it happened in the strangest place—Atlanta, Georgia.”10

Politics is what kept him out of boxing, and in the end, it was politics that got him back.

“He was,” Julian Bond said of Leroy Johnson, “almost a perfect politician.” In Atlanta, Johnson was known as a grassroots organizer and a savvy negotiator who wielded wide political influence in the Black community, delivering bloc votes for candidates in city, county, and statewide elections. In 1962, thanks to a massive Black voter turnout in the state’s 38th District, Democrat Leroy Johnson’s election made him the only Black legislator in the entire Deep South, shaping Atlanta’s image as the most progressive southern city. Johnson understood that politics was all about building relationships, so he cultivated connections with Atlanta’s Black and white politicians, city judges, local school board members, businessmen, clergymen, policemen, city employees, and the District Attorney’s Office. He was an active member of numerous Black civic organizations: the Atlanta Negro Voters League, the All Citizens Registration Committee, and the Georgia Association of Democratic Clubs, among others.11

The affable senator spoke with a disarming southern drawl, putting others at ease. His style and charm exuded power and affluence. A tall, lean man with a deep receding hairline, pencil mustache, and black horn-rimmed glasses, he dressed in tailor-made suits and wore a two-carat diamond ring. The Atlanta native had built a successful law practice, represented numerous Black celebrities, including James Brown, Otis Redding, and Hank Aaron, and made profitable investments in local businesses. Most days he drove to the Capitol in a Mercedes. Sometimes he drove a Jaguar or a Cadillac. When he first campaigned for a seat in the state senate, Johnson stopped smoking imported eight-inch cigars; his counselors advised him that smoking them in public made him look more like a crooked boss than a trustworthy legislator. Many whites resented his success and wealth, skeptical that a Black man could legitimately gain such affluence. Some critics even suggested that he was on the take.

Johnson’s path to power mirrored Atlanta’s emergence as the center of the southern Civil Rights Movement. Influential organizations, such as the Southern Regional Council (SRC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and SNCC, all called Atlanta home. So did the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, the largest privately held Black business in the country; the Citizens Trust Company; the Atlanta Daily World, the South’s leading Black newspaper; and Ebenezer Baptist Church, the pulpit of Martin Luther King Sr. and Jr. In 1961, a year after Black college students launched Atlanta’s sit-in movement, the city successfully desegregated its public schools, lunch counters, and other public facilities without violent confrontations. National reporters and photographers who covered massive resistance campaigns throughout the South marveled at Atlanta’s relatively peaceful integration. The city’s political leaders, conscious of national commerce, refused to let Atlanta become another Birmingham, known more for its brutal attacks on Black civil rights marchers than its business affairs.12

Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. explained that the “principal motivation” for desegregation “had been one of business pragmatism.” During the civil rights era, the city’s white leaders and a growing class of Black elites built a moderate coalition on the pillars of racial and economic progress. In their view, racial cooperation was inextricably linked to the city’s rapid financial growth. Atlanta was the home of major corporations: Coca-Cola, Delta Airlines, Southern Bell, and Trust Company Bank, among others. In the early 1960s, the rise of Atlanta’s commercial enterprises led to a booming population increase of 30,000 people each year. In 1962, the city authorized $120 million for new building permits. The construction of skyscrapers, massive hotels, the Memorial Arts Center, the Civic Center, Atlanta Fulton-County Stadium, Six Flags amusement park, and the expansion of the largest single airport terminal in the country made Atlanta a prime destination. In 1969, Mayor Allen boasted that Atlanta had become a truly “national city . . . known for gleaming skyscrapers, expressways, the Atlanta Braves and—the price you have to pay—traffic jams.”13

The story of Atlanta’s rise as the “South’s showcase, the Southern city of the future,” was not a simple story of economic development and successful integration. By the end of the 1960s, the city remained a focal point of white resistance to desegregation and white flight. Advances in the Civil Rights Movement attracted new Black residents to the city and sent whites retreating to the suburbs. Over the course of the 1960s, nearly 60,000 whites left the city, largely because they did not want to live in integrated neighborhoods or send their children to integrated schools. At the same time, 70,000 Black individuals moved into the city’s urban center, representing more than half of Atlanta’s population and a larger influence over city politics.14

The turning point of Black political empowerment came in 1969, when Leroy Johnson, Atlanta Life President Jesse Hill Jr., and the most prominent members of the Black political community focused their energy on adding African Americans to the sixteen-member Board of Aldermen, which previously seated only one Black member. The election of four additional Black members to the Board demonstrated the growing political power of the Black community. But, that same year, the biracial political coalition between white moderates and Black elites failed to agree on a candidate for the mayor’s race. While many moderate whites supported Republican Rodney Cook, African Americans overwhelmingly supported Vice Mayor Sam Massell, a Jewish candidate who had gained the public confidence of Johnson. With Johnson’s support, Massell won more than 90 percent of the Black vote in the mayoral run-off. Massell’s victory signaled the end of the old biracial political coalition and marked the beginning of a new era of Black political power in Atlanta—an era that began when Johnson negotiated the return of Muhammad Ali to boxing.15

Johnson had never promoted a boxing match before, but he knew the art of promotion. He was more than a shrewd politician; he was a power broker who wielded political capital. So when Harry Pett, a white local merchant, called and asked him about the chances of sponsoring an Ali fight in Atlanta, he was instantly intrigued.

In the first week of August 1970, Robert Kassel, an ambitious New York attorney and board chairman of Sports Action, Inc., called Pett, his father-in-law. Since 1967, Sports Action, Inc., created by Ali’s attorney Bob Arum and promoter Mike Malitz, had sponsored numerous boxing matches and closed circuit broadcasts. When Kassel called Pett, he had one question: was there enough Black political power in Atlanta to stage an Ali fight? “The man to see about that,” Pett answered, “is Leroy Johnson.”16

When Johnson spoke with Pett on the phone, “Old Leroy,” as his white allies affectionately called him, said that he needed to determine if there were any legal obstacles that would prevent Ali from boxing in the city. After a few phone calls he learned that there was no state boxing commission in Georgia, which meant that individual municipalities granted boxing licenses. The city’s Board of Aldermen, which included members who owed their positions to Johnson, held the authority to sanction prizefights. Kassel flew to Atlanta where he met Johnson in a motel room and made a deal: Sports Action, Inc. would underwrite everything for the fight and promote the ancillary rights. Johnson, along with Pett and Jesse Hill Jr., made House of Sports, Inc. responsible for obtaining Ali’s boxing license and securing a venue for the match.

The next day Johnson called Mayor Sam Massell and informed him of his plans to bring Ali to Atlanta. Massell, who had been in office for less than a year, was stunned at Johnson’s proposal. Massell said, “You want to bring who to do what? I don’t need to take all those brickbats on something like that.” Johnson pleaded, “Sam, I need your help. I can’t do this without you.” Johnson did not need to remind Massell that he had courted Black voters on the Mayor’s behalf. As a former selective service agent during World War II, Massell understood the laws regarding conscientious objectors and in his view Ali was a free man who had a right to earn a living. Ultimately, Massell hesitantly supported Johnson’s plan in exchange for a commitment from Sports Action, Inc. to deliver $50,000 to the city’s Commission on Alcoholism and Drugs. Finally, Massell said, “If anyone else had come in here and asked me for that, I’d told him to go straight to hell. But I can’t tell you no.”17

After Kassel learned that Johnson had the Mayor’s support, he asked, “What are you going to do about Maddox?” Lester Maddox was the Governor of Georgia and an ardent segregationist. Before he became governor in 1967, he was best known for his “family-friendly” restaurant in a working-class neighborhood on Hemphill Avenue. At the Pickrick (“You PICK it out, we RICK it up!”), Maddox served fried chicken, sweet tea, and old-fashioned southern hospitality. During the civil rights era, he published advertisements defending segregation on the basis of Christian principles, individual rights, and southern tradition. He also pointed to the financial success of the Black community in Atlanta as evidence that they benefitted from segregation. In his campaign for governor, his populist politics appealed to working-class whites. The bald, skinny man with rimless glasses, who looked like the pharmacist at the corner drugstore, railed against liberalism, welfare, and the dangers of “racial amalgamation.” Voters remembered how the day after the 1964 Civil Rights Act was passed, he turned away a group of Black customers, brandishing a pistol and arming whites with ax-handles. A year later, rather than comply with the law, Maddox closed the Pickrick’s doors and sold ax-handles as souvenirs.18

Leroy Johnson feared that Maddox, like every other governor in America, would deny Ali the opportunity to return to the ring. When they first met in the governor’s office, Johnson tried to appeal to Maddox’s politics, arguing that Ali did not want to be on welfare; he simply wanted to earn a living as a boxer. Unconvinced, Maddox resisted the arguments. Then Old Leroy tried a different approach. He remembered that the Governor’s son had recently been arrested for burglary. At the trial, the judge said that Maddox’s son deserved “another chance.” Johnson pressed the Governor, maintaining that Ali deserved “another chance,” too. “On with the fight,” Maddox told him.19

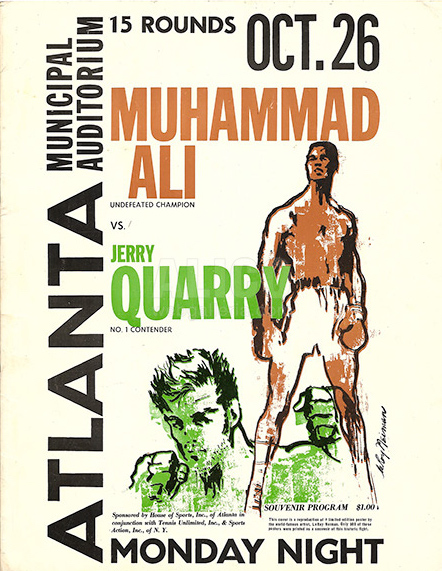

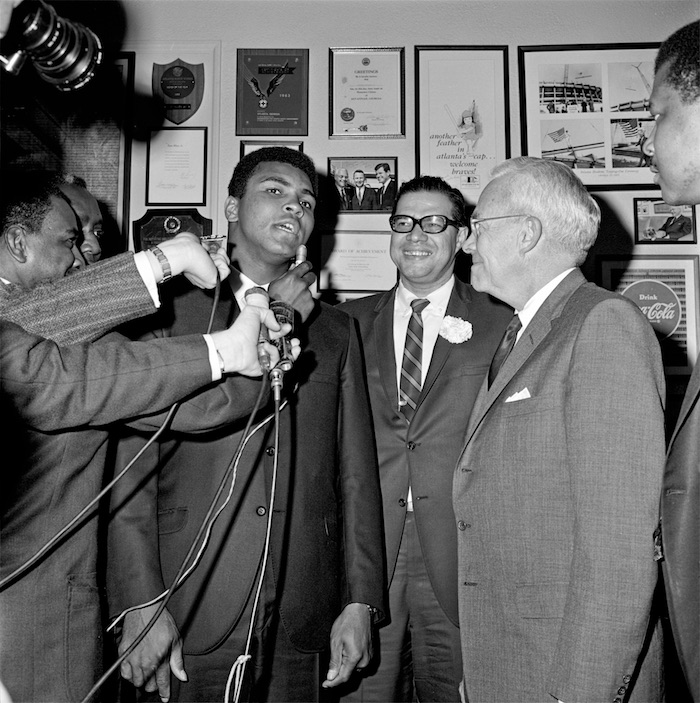

With the Governor’s support, Johnson and Kassel flew Ali to Atlanta for a press conference where they announced that he would fight heavyweight champion Joe Frazier on October 26 at Municipal Auditorium, though Frazier had not yet signed a contract. His manager, Yancey “Yank” Durham, doubted that Ali actually had a license. While photographers snapped pictures and writers scribbled quotes into their notepads, Ali and Johnson sat behind a press table, center stage, surrounded by the old boxing fraternity and Atlanta’s Black elite: Martin Luther King Sr., Vice Mayor Maynard Jackson, Reverend Samuel Williams, State Representative John Hood, Alderman Q. V. Williamson, and a group of Black college presidents, among many others. It was a striking scene, a picture of southern Black unity in triumph, an occasion owed to Johnson who had employed “the old approaches of the string-tie Southern politicians, sweet-talkin’ and favor swappin’ in back rooms,” putting “them to work for Black power, Atlanta style.”20

In the coming weeks reporters frequently asked Johnson why Atlanta—a southern city, of all places—was able to get Ali a boxing license. “I think it all goes back to Ralph McGill,” he said of the syndicated columnist and former editor of the Atlanta Constitution. As the voice of Atlanta, McGill’s calls to end segregation echoed throughout the country. “He taught whites and Blacks to get along with each other,” Johnson said. “There have been demonstrations here, but Black and white leaders have had enough sense to sit down with each other and let the conference table resolve our difficulties. We’ve made greater progress in Atlanta than any other city in the South in the past 10 years.”21

By the 1960s, as white moderates increasingly embraced McGill’s message of racial cooperation, Black elites like Leroy Johnson became proud promoters of the city’s progressive image. In a culture of boosterism, Johnson framed Atlanta as the capital of the New South, a tolerant city that embraced change. This image of the city, along with its booming businesses, made it an attractive Sunbelt market for professional sports. In 1966, a year after Fulton-County Stadium was built, the Milwaukee Braves, along with Black star Hank Aaron, moved into the stadium, as did the upstart Falcons of the National Football League. In 1968, the St. Louis Hawks’ relocation brought the city its first professional basketball franchise. In just three years, three professional sports teams had moved to Atlanta, completing its apparent revolution from a southern city into a major national city.

The presence of three integrated sports teams helped broaden the racial consciousness of Atlanta’s white sports fans and further demonstrated that the city was changing into one of broader significance. In this context, Ali’s return to boxing galvanized the city’s historical movement toward racial progress and the coronation of Atlanta as the sports capital of the South. For Johnson and his partners, the Ali–Frazier match represented an opportunity to “sell the Atlanta story to the world,” but Maddox was not quite ready to accept Ali’s return. A few days after he announced his support for the match, he recoiled: if he had known that Ali was convicted of draft evasion, he would have never approved the fight. Legally, however, there was nothing that the governor could do to stop it. He didn’t like it, but the fight would go on.22

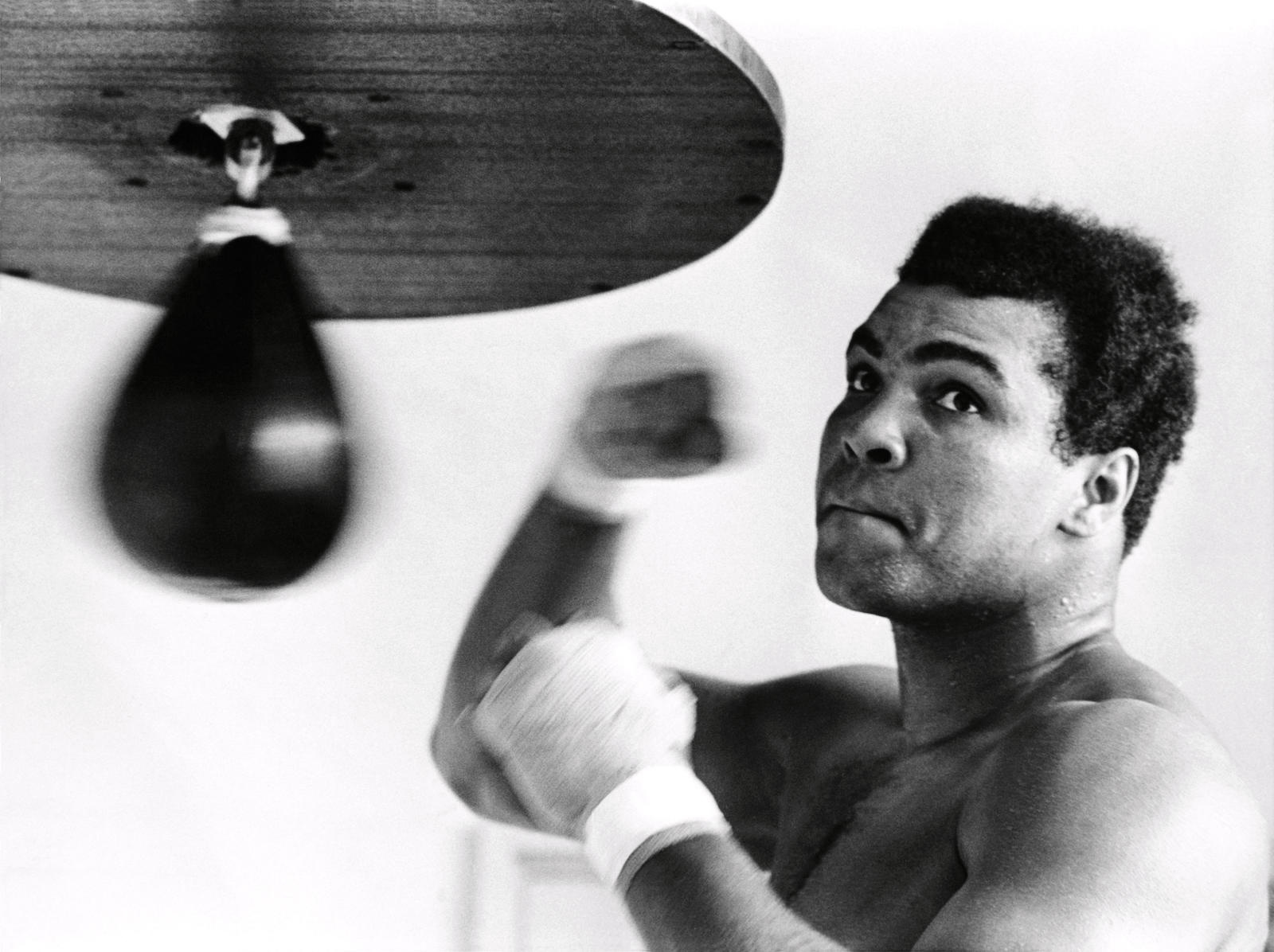

On September 2, Muhammad Ali appeared in an eight-round exhibition at the Archer Gymnasium on the Morehouse campus. Leroy Johnson and Jesse Hill deliberately chose a campus arena insulated within a Black neighborhood to avoid potential disruptions from the Klan or the White Citizen’s Council. Inside the cramped, muggy gym, 3,000 restless fans eagerly awaited the sound of the bell. Ali was scheduled to spar with three underwhelming opponents: two rounds with Rufus Brassell; two rounds with Johnny Hudgins; and four rounds with George Hill. Since Ali last stepped into the ring more than three years earlier, he had gained weight, especially around his softened midsection; his face was rounder, too, though he was reportedly in “far better shape than most campus lecturers.” First he squared off against Brassell for two rounds, tossing light jabs as he bounced around the ring. In the next two rounds, sweat poured from his body as he drifted away from Hudgins, his hands held low. He tired quickly in the heavy humid air. There were no memorable blows, no knockouts, no dancing. The fans started booing him.23

After the first of four rounds against Hill, Ali returned to his corner, breathing heavily. Drew “Bundini” Brown, Ali’s close friend, cornerman, and motivational cheerleader, snapped, “What’s the matter?” Ali gasped, “I’m tired! I’m tired, Bundini. What do they expect? This is an exhibition.” Fuming, Bundini barked in Ali’s ear, “This ain’t no goddam exhibition, n—–. This the Resurrection! Shorty ordered a Resurrection!” A converted Jew, Bundini called God “Shorty,” and he strongly believed in Shorty’s ability to dictate the fate of Ali. Bundini reminded Ali of all that he had been through, how the people had stood behind him, and how they expected him to rise up and fight—fight for them. “Them people out there, they bringin’ you back to life,” he preached. “The Government’s ready to bury your ass underneath the jail. But they come to dig you out the grave. Tired? When you spendin’ them five years in jail you get tired. Not now, Champ, not now! Now’s your Resurrection Day! Straighten Up!”24

In the last few rounds, Ali showed signs of regaining his old form, weaving and bobbing, throwing quick jabs and rapid combinations. From the corner, Bundini implored him, “Dance! Dance, Champ! Dance!” The crowd erupted in the final round when he performed the Ali shuffle, a quick flurry of steps that disoriented his opponent. When it was over, Ali admitted that he was in no shape to fight Joe Frazier. But it didn’t really matter because he would not fight him, at least not yet. When Johnson contacted Yank Durham, Frazier’s manager remained unconvinced that the senator could stage a title fight. Durham said that the champion had already made plans to fight Bob Foster. Ali would have to fight somebody else in Atlanta.25

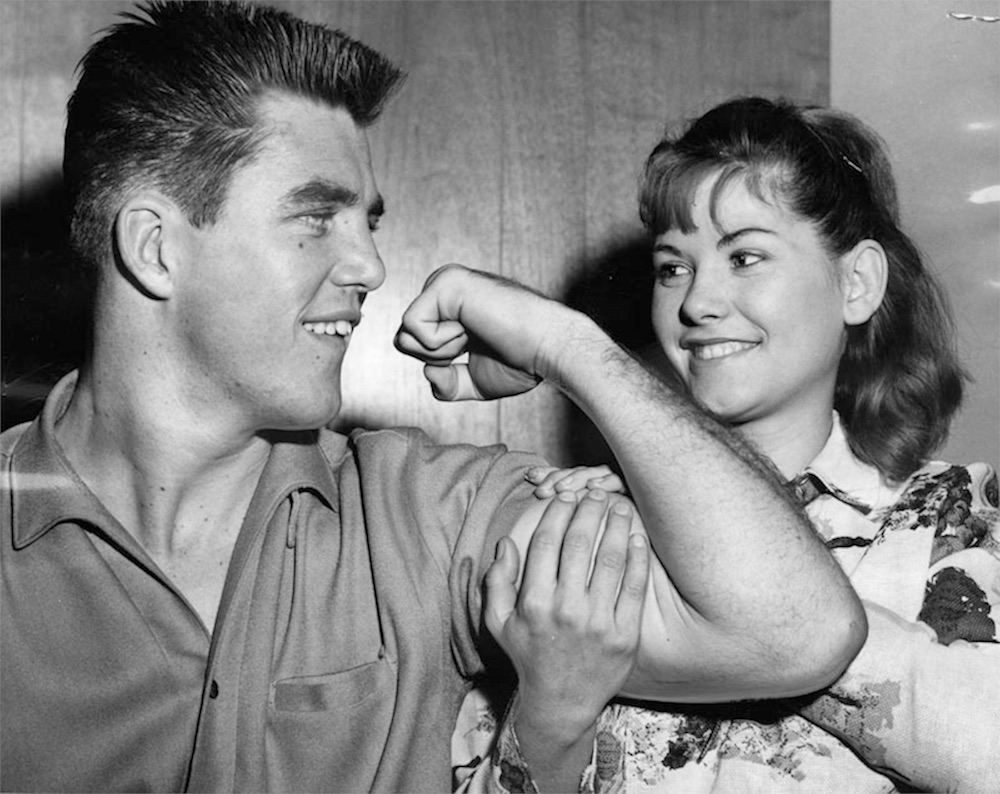

When Harold Conrad suggested that the promoters sign Jerry Quarry for the fight, Ali grinned and said, “That’ll give Whitey something to root for.” If Whitey was looking for a Great White Hope in a heavyweight division dominated by Black boxers, Quarry was it. He had the look of a fighter. His pale, flat, unshaven face with a broken nose and a slightly protruding lower jaw revealed his “Irish ferocity.” He had the body of a brawler, thick sloping shoulders, broad chest, and toned abdominals. He was, one writer observed, “a prize pit bulldog, a man bred for the ring.” The heavyweight contender from California belonged to that patriotic group of the white Silent Majority who believed that Ali should have fought in the army. Quarry echoed the sentiments of law-and-order Reagan Republicans, who were tired of race riots. “The Black man,” Quarry said, “is yelling about prejudice. What makes me mad is the Government is afraid to do something about what they’re doing. The Black man is being prejudiced against the white man by those who don’t want equality but superiority. But everybody’s afraid to sock it to the Black man.”26

When he agreed to sock it to Ali, Quarry’s career instantly took on a larger political significance. Quarry tapped into the very tensions that drove “white flight”—open housing, busing, affirmative action, and welfare for the Black community. In an age of white ethnic cultural pride, Quarry was an incredibly popular fighter among white boxing fans, especially “those who thrust out their fists as answers to campus revolution and Black insurrection.” But for many African Americans and white liberals, Quarry reminded them of the faces they saw “peeping out from behind a police visor or supporting a flag-decaled construction hat.” Quarry was consciously aware that he was carrying the hopes of members of his race. “Boxing needs a white champion to replace Cassius Clay,” he said in 1968, refusing to acknowledge Ali’s Muslim name. “I’m the only one who can really help boxing.”27

Ali promised that his comeback was not “going to be spoiled by no Great White Hope.” In the weeks before his fight with Quarry, he had become interested in the career of Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight champion, who made a career of pummeling white hopes. Ali’s fascination with “Papa Jack” occurred at the same time that “The Great White Hope,” an award-winning Broadway drama based on Johnson’s life, became a sensational motion picture. At the height of Johnson’s reign, from 1908 to 1915, boxing promoters searched for a white fighter who could end his career and restore the title on the white side of the color line. Johnson defied Jim Crow custom, refused to bow to white men, and openly flaunted his relationships with white women. After the federal government convicted him of the Mann Act, a Progressive Era law designed to prevent the interstate travel of women for “immoral purposes,” Johnson fled the country and eventually lost the title to a white hope in Cuba. In the government’s persecution of Johnson and his exile from boxing, Ali saw parallels between their lives. “That’s me,” he said. “You take out the white women and [Johnson’s story] is about me.”28

Ali’s match against Quarry was about something more than defeating a modern-day White Hope. This fight was about Black hopes—the deep desire for Black freedom and political independence. Ali did not return to the ring to disprove the supremacy of a white boxer. He fought not only to regain his life from those who persecuted him, but also to fulfill the dreams and aspirations of his race. He was fighting for Black empowerment. He was fighting for justice.

He was fighting for Black empowerment. He was fighting for justice.

Three weeks before his match against Quarry, Ali took a step closer toward redemption when a federal court ruled that the NYSAC could not deny him a boxing license because he had been convicted of draft evasion. After Ali’s lawyers demonstrated that the commission had “granted, renewed, or reinstated boxing licenses” to more than 240 “applicants who had been convicted of one or more felonies, misdemeanors, or military offenses involving moral turpitude,” the Judge declared that the suspension of Ali’s license was completely arbitrary and discriminatory. Now, if Ali defeated Quarry and proved that he was once again an elite boxer, there was no doubt that promoters would pursue a title match between him and Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden. But first, he had to defeat Quarry.29

Five days before the bout, Governor Lester Maddox declared that Monday, October 26, the day of the fight, would be a “Day of Mourning.” At a press conference from his office, he encouraged the people of Georgia to boycott the match, though his appeal failed to incite any massive protests. Maddox had even asked State Attorney General Arthur K. Bolton if the state had the legal power to stop the fight. Bolton replied that there was no state law “which disqualifies a person from participating in a sporting event because of a pending criminal conviction or a final criminal conviction.” In his attempt to disrupt Ali’s comeback, Maddox proved that not everyone in Atlanta had embraced the myth that the “city was too busy to hate.”30

Mayor Sam Massell issued his own proclamation, declaring a “Sports Spectacular Weekend”—a weekend of sporting events that included a Falcons football game, a Georgia Tech football game, and a Hawks basketball game. In the tradition of Atlanta boosterism, Massell announced that these sporting events “brought to Atlanta the attention of people around the globe and help illustrate to those people the good sportsmanship of all Atlantans.”31

In Atlanta, sportswriters noticed a more subdued Muhammad Ali. In the days before the fight, he did not brag or boast about which round he would drop Quarry to the canvas. He did not talk about his pending court case or the Vietnam War. Nor did he criticize the South or Atlanta for its race relations. He sounded more like one of the city’s boosters. He said, “People ask me, ‘You really gonna fight down there in Georgia? Down there where Lester Maddox is? You’re not scared?’ Shoot, I been out there running on them red clay roads at five, six o’clock in the morning and people come by, they spit tobacco and say, ‘How you doin’, boy? How’s it goin’ champ?’ I say, ‘It’s just fine, sir.’” Ali drew a discernable color line between the North and the South as well, framing the South as a place where people were more honest about how they felt about race and integration. “These newspapers down here,” he said, “they don’t try to embarrass you. Up North they say, ‘What’s your religion? What meeting you go to last week?’”32

Despite Ali’s public statements, Leroy Johnson worried that the Klan might attempt to harm him. So, Johnson sent him to his three-bedroom cottage about fifteen minutes from downtown Atlanta. Five minutes from the nearest paved road, Ali and his entourage seemed safe in a secluded cottage surrounded by a small lake and a deep forest filled with brightly colored autumn foliage. In the early morning light, when Ali ran the dirt roads, he could hear the rattling sound of trains echo through the backwoods. Inside the country house, Ali and his friends made a complete mess. Crumpled newspapers and magazines, dirty laundry, shoes, and empty Coke bottles covered the living room floor. The curtains were drawn, blocking out the sunlight so that he could watch old fight films projected onto a wrinkled bed sheet.33

In the days before the match, armed guards greeted newsmen, photographers, and other visitors. After finishing his training in Miami, Ali planned to return to Atlanta, but before he did, he received a package with a black Chihuahua inside, its head severed, and a message: “We know how to handle black draft-dodging dogs in Georgia. Stay out of Atlanta!” At his home in Philadelphia, cranks harassed Ali’s wife, calling her in the middle of the night. The Atlanta police received threatening letters, too. One day, before sunrise, the crackling sounds of gunshots peppered Senator Johnson’s cottage. “Get down, Champ! Get down!” Bundini Brown yelled. Ali could hear the gunmen rustling through the trees. “You Black sonofabitch! Get out of Georgia! You draft-dodging bastard!” Fortunately, no one was hurt. After everyone’s heart rate came back down, the phone rang. He picked it up. “N—–, if you don’t leave Atlanta tomorrow, you gonna die,” a high-pitched voice warned. Ali hung up the phone, but it rang again. “Listen, n—–, you go into that ring Monday night, you’ll never get out. I’ll die just to see you die! Ain’t gonna be no fight in Atlanta.”34

On the day of the fight, the phone kept ringing at the cottage. If Ali was scared, he did not show it. He did not pace the living room or sleep like he usually did to calm his nerves. Instead, he spent most of his time on the phone taking calls from friends and celebrities. “Sidney Poitier!” Ali boomed into the receiver. Whitney Young, Hank Aaron, Gale Sayers, and Willie Mays called, too. When he was not on the phone, he sat on the edge of the couch watching old boxing movies of Jack Johnson flickering on the screen.35

Ali’s eyes lit up when “the Reverend” strode into the cottage. The Reverend was Jesse Jackson, a flamboyant, ambitious young leader of SCLC’s Operation Breadbasket. His presence at the cottage spoke to Ali’s ability to bring together different ideological views of the Black community. Unlike Ali, Jackson was a liberal integrationist who called for racial cooperation, not separatism. He saw Ali’s fight through the prism of the long Black Freedom Struggle, as a force of Black unity and resistance.36

If Ali lost later that evening, he said, “Symbolically, it would suggest that the forces of blind patriotism are right, that dissent is wrong, that protest means you don’t love the country . . . They tried to railroad him. They refused to believe his testimony about religious convictions. They took away his right to practice his profession. They tried to break him in body and in mind. Martin Luther King used to say, ‘Truth crushed to the earth will rise again.’ That’s the Black ethos. And it’s happening here in Georgia of all places, and against a white man!”37

For Jackson and many others, Ali spoke the truth. Jackson saw him as an emblem of Black redemption. Ali, too, understood that this was the biggest fight of his career because his people were counting on him to win. If he lost, millions of people around the world would feel like they lost, too. “If I lose I will not be free,” he added. “I’ll have to listen to all this about how I was a bum, I was fat, I joined the wrong movement, they misled me. So, I’m fightin’ for my freedom.”38

If I lose I will not be free. I’ll have to listen to all this about how I was a bum, I was fat, I joined the wrong movement, they misled me. So, I’m fightin’ for my freedom.

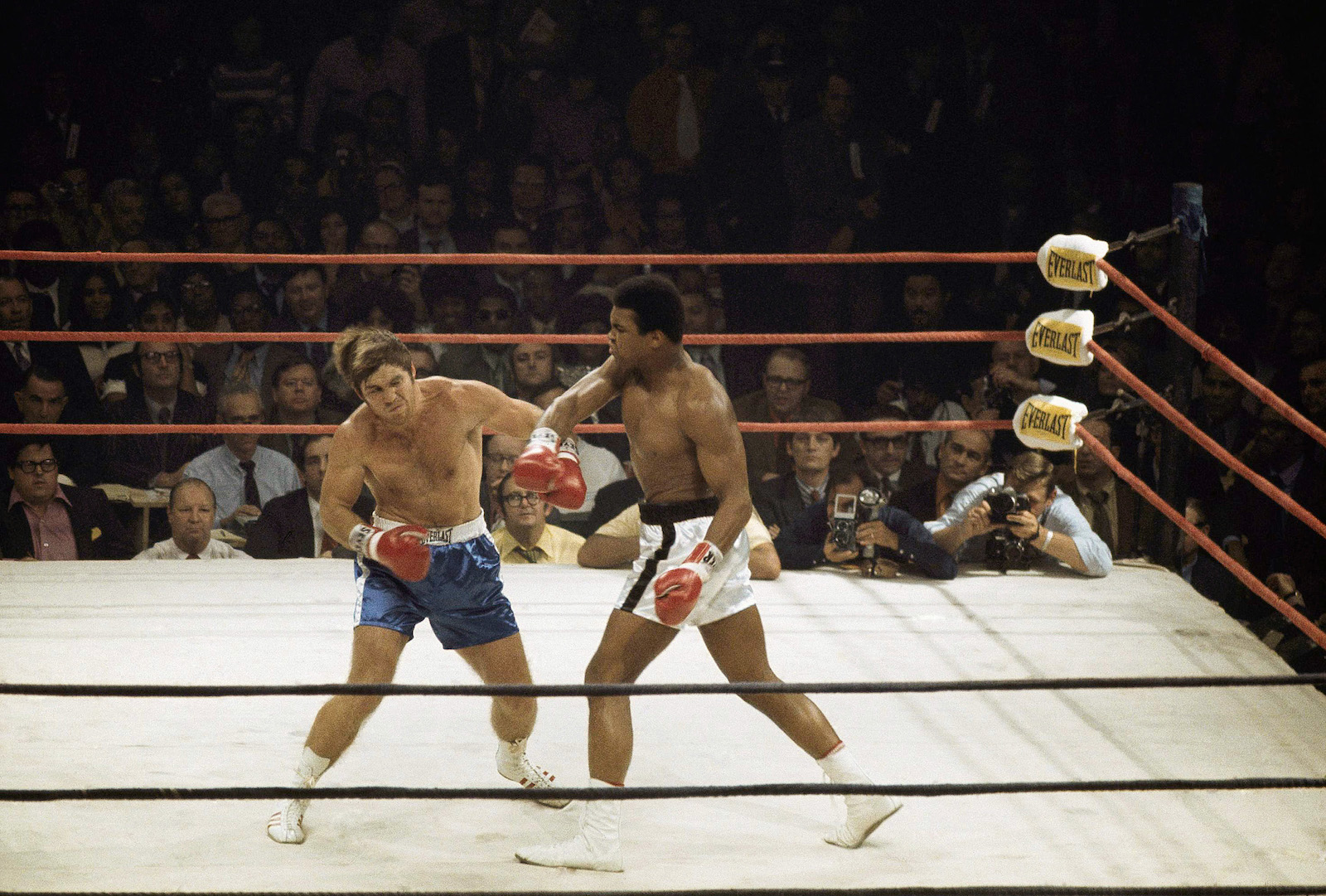

On October 26, 1970, at around 10:30 p.m., a bodyguard shadowed Ali as he moved through a narrow aisle toward the ring inside Municipal Auditorium. After Quarry received a mixed reaction from the overwhelmingly Black crowd, Ali ducked through the ropes as a chorus of cheers rang throughout the building. Few writers gave Quarry any chance of beating him. According to the betting line, Quarry was a 17–5 underdog. The Chicago Tribune’s David Condon opined, “Personally, I do not think that Quarry could irritate Clay even if they let Quarry use one of Lester Maddox’s ax handles.” Though most writers were confident of an Ali victory, a wave of uncertainty silenced the anxious crowd just before the opening bell. People wondered how Ali, who had lost more than 25 pounds in six weeks—slimming down to 213 pounds—and had not fought in a professional match in more than three years, would perform when it mattered most.39

During the opening ceremonies, Leroy Johnson stood in the center of the ring in front of 5,000 applauding fans and more than 100 million viewers watching around the world. As promised, Johnson presented a $50,000 check to Mayor Mas-sell for the city’s drug abuse prevention program. For his own efforts, Johnson collected approximately $175,000 of the fight’s $4 million gross. After Massell gladly accepted the check, he declared into a microphone that this fight was a “demonstration in democracy.” Sitting near ringside, a Black fan in a white tuxedo agreed, shouting, “Right on, baby. That cat’s gonna show whitey!”40

Finally, the bell rang. Ali came out dancing with his sparkling white boots. He slipped a few jabs and threw hard combinations to Quarry’s head, danced, and jabbed again. In the third row, surrounded by Black dignitaries and celebrities, Julian Bond could not stay seated. He mirrored Ali, throwing punches at the air as if he too was fighting against all those critics who claimed that he was unpatriotic for speaking out against the war. In the third round, Ali sized up Quarry and stabbed him with a cutting right jab, gashing the brow bone above his left eye, a cut that would later require eleven stitches. Blood trickled down Quarry’s face, forcing the referee to call the fight. It did not matter that the fight lasted only three rounds. The people who came to see Ali win left feeling vindicated.

Looking back, the Ali–Quarry fight marked a turning point in boxing history. Leroy Johnson and his business partners had not only resurrected the career of Muhammad Ali, but they had also staged a match that breathed new life into a sport that critics pronounced dead. Sportswriters and fans often recall that Ali’s fights in the mid-1970s in Zaire and the Philippines launched the globalization of boxing. But the worldwide attention generated by Ali’s comeback and the emerging satellite communications that allowed people across the world to watch the fight helped transform boxing into a global sports spectacle in 1970. The international media coverage of the Ali–Quarry bout demonstrated that there was a global audience for boxing, setting the stage for numerous heavyweight matches across four different continents during the next decade.41

The Ali–Quarry fight also left a lasting imprint on the political culture of Atlanta. It was, according to the Constitution’s Reg Murphy, “among the epic events in Atlanta history.” Eight months before the Supreme Court reversed Ali’s conviction, Leroy Johnson and Atlanta’s most influential African Americans leveraged their political capital by securing his return to the ring. This would not have been possible without the hard fought victories of Atlanta’s civil rights activists who challenged the social order of the South. The city’s Black and white leaders’ shared vision of economic development and racial cooperation enabled Johnson and his partners to host an international sports spectacle that enhanced Atlanta’s reputation as the most progressive city in the New South.

Murphy, a white man, recognized that by promoting Ali’s comeback, Johnson and other Black leaders had improved the city’s race relations by dispelling old stereotypes of “Black Americans as shuffling, nodding failures.” The fact that Atlanta, the southern capital of the Civil Rights Movement, welcomed Ali meant that the city had embraced change in a way that no other southern city did—and maybe no other American city could. “That is not to say Atlantans and Georgians have either been overcome with Ali’s political views or that all of them think it is a good thing for the fight to be staged here,” he wrote. “Many of them do not think it is a good thing. But,” he added, “they have tolerated it,” and that was “a good thing for the city.”42

This essay first appeared in the Summer 2015 issue (vol. 21, no. 2).

John Matthew Smith specializes in the history of sports, race, and American culture. He is co-author of Blood Brothers: Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, and the Ring of Hate (Basic Books, 2016).NOTES

- Mark Kram, “He Moves Like Silk, Hits Like A Ton,” Sports Illustrated, October 26, 1970, 18); Kram, “Smashing Return of the Old Ali,” Sports Illustrated, November 2, 1970, 18.

- Jack Richardson, “Ali On Peachtree,” Harper’s, January 1971, 46, 49.

- Howard L. Bingham and Max Wallace, Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight: Cassius Clay vs. The United States of America (New York: M. Evans and Company, Inc., 2000), 160.

- Phyl Garland, “Atlanta: Black Mecca of the South,” Ebony, August 1971, 152–57; Matthew Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2006), 11; Furman Bisher, “After the Torture, A Purpose Served,” Atlanta Journal, September 3, 1970, 1D.

- David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, October 24, 1970, B3.

- Bingham and Wallace, Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight, 118.

- Julian Bond interview in Thomas Hauser, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 211.

- Mike Marqusee, Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties (London and New York: Verso, 2000), 214.

- Muhammad Ali, “I’m Sorry But I’m Through Fighting Now,” Esquire, May 1970, 120–22.

- Conrad interview in Hauser, Muhammad Ali, 208.

- Bond interview in David Davis, “Knockout: Muhammad Ali, Atlanta, and the Fight Nobody Wanted,” Atlanta, October 2003, 120; Lerone Bennett, Jr., “Georgia’s Negro Senator,” Ebony, March 1963, 28; Stephen Lesher, “Leroy Johnson Outslicks Mr. Charlie,” New York Times Magazine, November 8, 1970, 34–36.

- Frederick Allen, Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City, 1946–1996 (Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1996), 93–94; Gary Pomerantz, Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn Avenue: The Saga of Two Families and the Making of Atlanta (New York: Scribner, 1996), 251–69.

- Pomerantz, Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn Avenue, 313; Dominick Sandbrook, Mad as Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), 130.

- Sandbrook, Mad as Hell, 130; Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005), 234.

- Pomerantz, Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn, 379, 384–91; Alton Hornsby, Jr., Black Power In Dixie: A Political History of African Americans in Atlanta (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009), 121–25.

- Lesher, “Leroy Johnson Outslicks Mr. Charlie,” 50. Sports Action, Inc. was a subsidiary promotion enterprise of Tennis Unlimited.

- Lesher, “Leroy Johnson Outslicks Mr. Charlie,” 50.

- Kassel interview in Davis, “Knockout: Muhammad Ali, Atlanta, and the Fight Nobody Wanted,” 121; Reese Cleghorn, “Meet Lester Maddox of Georgia, ‘Mr. White Backlash,’” New York Times Magazine, November 6, 1966, 27–28, 40, 42, 46, 50.

- Michael Arkush, The Fight of the Century: Ali vs. Frazier, March 8, 1971 (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008), 18–19.

- Budd Schulberg, Loser and Still Champion: Muhammad Ali (New York: Popular Library, 1972), 68.

- Kram, “Welcome Back, Ali!” 23.

- Muhammad Ali–Jerry Quarry Official Souvenir Program, October 26, 1970, courtesy of Mark McDonald.

- Schulberg, Loser and Still Champion, 78.

- Muhammad Ali with Richard Durham, The Greatest: My Own Story (New York: Random House, 1975), 279–80.

- Ibid., 280–81.

- Schulberg, Loser and Still Champion, 78; Furman Bisher, “The Quarry Corporation,” Atlanta Journal, October 20, 1970, 1D; Richardson, “Ali on Peachtree,” 49; Mark Kram, “The Brawler at the Threshold,” Sports Illustrated, June 16, 1969, 29.

- Richardson, “Ali on Peachtree,” 49; Dave Anderson, “Quarry Gains Title Final, Stopping Spencer in 12th,” New York Times, February 4, 1968, S1, (hereafter, NYT). On “white flight,” see Kruse, White Flight.

- “Ali Vows Defeat for ‘White Hope,’” Atlanta Journal, October 14, 1970, 4D; James Earl Jones interview in Hauser, Muhammad Ali, 198.

- Craig R. Whitney, “3-Year Ring Ban Declared Unfair,” New York Times, September 15, 1970, 56.

- Tom Linthicum, “Maddox Declares Day of Mourning,” Atlanta Constitution, October 23, 1970, 1D; Lester Maddox to Arthur K. Bolton, September 21, 1970, Governor’s Subject Files, Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) October 1970, Georgia Governor’s Office, RG 1-1-5, Georgia Archives.

- Darrell Simmons, “Legal TKO Ends Maddox Fight Ban,” Atlanta Journal, September 30, 1970, 1D; Morris Shelton, “Maddox, Massell Spar Over Cassius,” Atlanta Journal, October 23, 1970, 2A.

- Darrell Simmons, “Bonavena Not for Ali, Quarry,” Atlanta Journal, October 23, 1970, 6C.

- George Plimpton, Shadow Box (New York: Putnam, 1977), 151–52; Schulberg, Loser and Still Champion, 86; John Hall, “Not Just Quarry, I’ve Got to Beat Critics, Too—Clay,” Los Angeles Times, October 23, 1970, C1.

- Arkush, The Fight of the Century, 38–39; Ali with Durham, The Greatest, 302, 315–18.

- Leonard Shecter, “The Rise and Fall of Muhammad Ali,” Look, March 9, 1971, 62.

- On Jesse Jackson’s politics during the 1960s see, Barbara A. Reynold, Jesse Jackson: The Man, The Movement, The Myth (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1975).

- Schulberg, Loser and Still Champion, 88.

- Kram, “He Moves Like Silk, Hits Like A Ton,” 18.

- David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, October 21, 1970, C3.

- Hugh Merrill, “The Black and Famous Show Up at Big Bout Here,” Atlanta Journal, October 27, 1970, 1A.

- Lewis A. Erenberg, “‘Rumble in the Jungle’: Muhammad Ali vs. George Foreman in the Age of Global Spectacle,” Journal of Sport History 39 (Spring 2012): 81–97.

- Reg Murphy quotes from “Sport and Sociology at the Auditorium,” Atlanta Constitution, October 28, 1970, 4A; and “Ali and Atlanta,” AC, October 26, 1970, 4A. On the globalization of the South, see James C. Cobb and William Stueck, eds., Globalization and the American South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005).