“‘Men say mill folks are rotten / an’ mean down to the core, / But if you seen your chillern starve, / wouldn’t you ask fer more?'”

While doing research on textiles during the Great Depression, I found this poem about Ella May Wiggins on the March 8, 1932 editorial page of the Greensboro Daily News in a regular column titled “Shucks and Nubbins.” The author signed the piece with the initials S. A. J., but did not provide any other information about the poem.

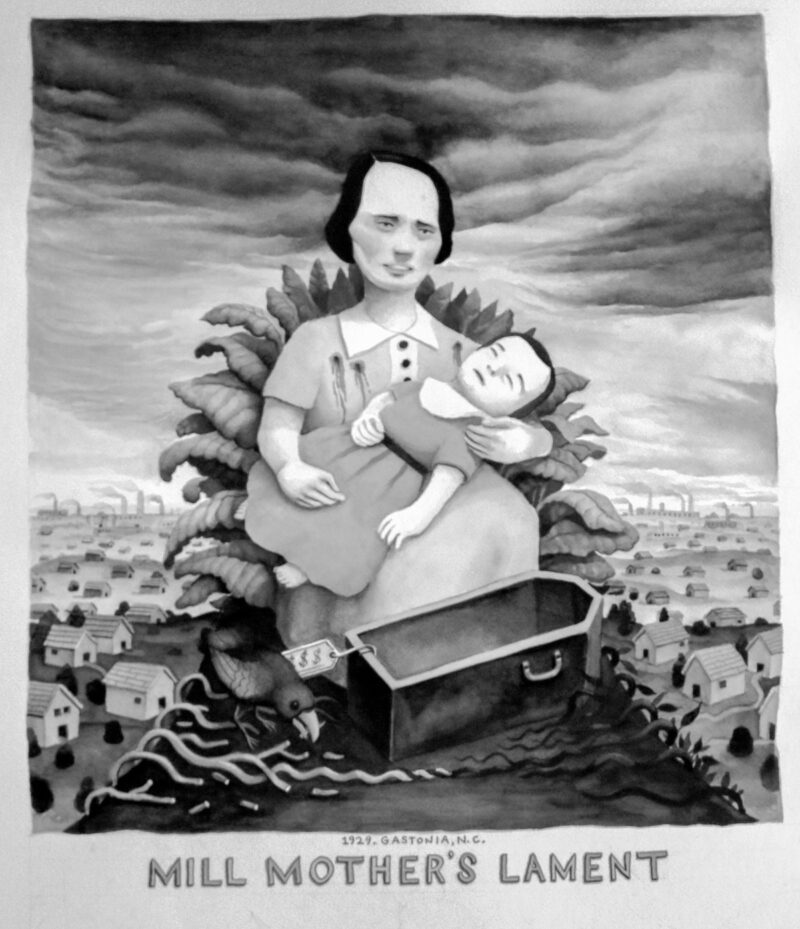

During the 1929 strike at Gastonia’s Loray Mill, Wiggins became the campaign’s “poet laureate” through the ballads she composed using melodies from contemporary hillbilly music. Her murder by a mill thug made her a martyr for the cause and led proletarian novelist Mary Heaton Vorse to transform her into a heroic figure. Folk music collector Margaret Larkin took her songs north where they became inspiration for Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.

This poem offers an unusual point of view. It is a lament from a fellow striker that Wiggins’s death did not bring any resolution of the workers’ complaints. It begins at the funeral where her children are “a mournin’ and a cryin’ out their eyes.” It then flashes back to her murder while traveling to a rally in a truck where “blood now stains the seat where Ella May was struck.” The poet offers a novel and dramatic description of the aftermath when quiet falls over the scene because, as the poet explains, “the man who had shot her really hadn’t come to kill.” When the poem returns to the funeral, the reader finds that union leaders plan to take her children on a northern publicity tour, but the locals prevent that by placing them in an orphanage. The accusation that union leaders wanted to “kidnap” the children later appeared in conservative writing. The poem continues with an erroneous reference to Wiggins’s four husbands. At its close, the poet proclaims that the strike and the murder did nothing to resolve labor’s complaints because they had been forgotten, and the residents of Gastonia “can’t get up much feeling twixt the owner and the hand.” Uncertain about a solution, the poet ends with “it seems like God should take a hand to clear us of this mess.”1

This poem offers tantalizing new elements to the story of Ella May Wiggins and her murder, but we are left with no certainty about the accuracy of these details. We only have these few words.

“Saga of Ella May Wiggins”

They stopped off the spinnin’

…and shet down the warps,

So all the folks could take a look

…at Ella May’s corpse.

Twas a sad, sad, day and

…many a man did weep,

As they looked on Ella’s face

…in its last and final sleep.

Her children were a mournin’

…and a cryin’ out their eyes,

Fer their maw who had done went

…to her home up in the skies.

“I’m returnin’ to the mountains,”

…as often Ella said,

But she’ll never see the mountains

…fer poor Ella May is dead.

Now folks I’ll tell the story of how

…I seen poor Ella die,

And maybe you’ll forgive me

…if I sometimes stop to cry.

The folks in town had beat us up

…almost beyond belief,

And when the cops rush up on us

…we killed the police chief.

Nobody knowed who done it

…but ‘round us bullets sang,

An’ folks were all a shouting’

…by God we’ll lynch this gang.

So all the striker boys

…was languishin’ in jail,

Cause we couldn’t raise the money

…to git ‘em out on bail.

The leaders called a rally

…to give the boys some cheer,

An’ fore the day was over

…thet rally cost us dear.

The vig’lance committee said,

…“no speaking we’ll abide,

If we have to put some bullets

…in them dirty Roosians’ hides.”

The strikers from Besmer City

…were all loaded in a truck,

And blood now stains the seat where

…Ella May was struck.

We were a-comin’ down the road

…and the driver he did swear,

When a car filled full of vigilants

…crashed into us there.

Both sides were all excited

…and let some bullets fly.

An’ I looked ’round just in time

…to see poor Ella die.

A stray ball had caught her

…an’ she gave a sudden start,

As the leaden slug smashed

…into poor Ella’s heart.

Then ever’thing was quiet

…and ever’thing was still,

Fer the man who had shot her

…really hadn’t come to kill.

I watched thet man, his body shrank

…an his face was awful still,

“My God,” he said, “that I would live

…to see the day I’d kill.”

But they had a scrumptious burial

…and all the folks thet came,

Comforted the mourners sayin’

…“Ella looks just the same.”

Said leaders: “we’ll take her kids

…and shout out till it rings.”

But the town folks took the kids

…an’ put ‘em at Barium Springs.

Ella had had four husbands

…an’ each she had loved dear,

But when the poor gal got bumped off

…nary one of ‘em was near.

And now the strike is over

…And people has most forgot,

Of the death of two poor people

…They don’t keer, like as not.

Then can’t get up much feelin’

…twixt the owner and the hand,

But mabe it’s just because

…they both can’t understand.

Men say mill folks are rotten

…an’ mean down to the core,

But if you seen your chillern starve,

…wouldn’t you ask fer more?

The owners say they can’t pay more,

…the workers can’t live on less;

It seems like God should take a hand

…to clear us of this mess.

This piece first appeared in the Fall 2015 Music Issue (vol. 21, no. 3).

Annette Cox focuses on the southern textile industry and has published in the Journal of Southern History, Business History Review, and the North Carolina Historical Review. She has presented papers on textile history at international conferences in Montreal, Paris, Scotland, Japan, and Portugal.

Header image: Gastonia, N.C. Loray Cotton Mill, from North Carolina Postcards, the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC–Chapel Hill.NOTES

- W. T. Bost, “Among Us Tar Heels,” Greensboro Daily News, June 4, 1946, 4. See this fine introduction to the murder and her music in Patrick Huber, “Mill Mother’s Lament: Ella May Wiggins and the Gastonia Textile Strike of 1929,” Southern Cultures15, no. 3 (Fall 2009): 81–110.