The only time I remember reading about my hometown of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in my K–12 education was during my senior year Advanced Placement English class. We read The Unvanquished by William Faulkner. In the opening scene, Loosh, a man enslaved by the Sartoris family, destroys a map of Vicksburg that the Sartoris child, Bayard, had made, using wood chips and a hoe to depict the terrain of the much-discussed Civil War battle.

Bayard was obsessed with Vicksburg because, at the time, it was debatably the most crucial city in the nation. Abraham Lincoln called it “the key” to the South: “Let us get Vicksburg, and all that country is ours.” His foe, Confederate president Jefferson Davis, recognized the city’s importance too, calling it the “Gibraltar” of the western front: “the nailhead that holds the two Souths together.”

Loosh destroyed Bayard’s map by sweeping “the chips flat” as he laughed and exclaimed, “There’s your Vicksburg.” It turns out the Union had already won the battle. Bayard had not yet heard, but Loosh had. Loosh’s wife, Philadelphy, scolded him for rubbing the Union victory in the boy’s face. But Loosh couldn’t help himself; he knew his life, his South, and his nation would never be the same. He would soon be free.

Loosh is a precursor to all the Black southerners, like me, who are tired of looking at white southerners’ representation of the region. Loosh’s destruction of the map anticipates my own frustration with representations of Vicksburg created primarily by white male authors. He anticipates my creation of poems and short stories that center on people like him and his descendants.

I was born in Vicksburg and lived there for the first eighteen years of my life. I spent the next four years in Starkville as an undergraduate at Mississippi State University—far enough from home for me to feel independent and close enough not to get homesick.

Moving to England and then Boston has been a different experience. When I left Mississippi for England at age twenty-one, I knew very little about my hometown, even though I always bragged about it and defended it against other people’s negative stereotypes. I learned quickly that I would have to arm myself with knowledge to be more convincing and, more importantly, to know myself.

Hundreds of books have been written about my hometown by authors who are white men. The books say very little about the majority-Black population who live or have lived in Vicksburg; instead they focus on the Civil War battle. I have tried to read most of them but rarely completed them. Like Loosh, I wanted to destroy their representations of Vicksburg. Most of the books fail to show the Vicksburg I know, or my grandparents knew, or the enslaved knew.

Nonetheless, I have learned that Vicksburg was an extremely wealthy city during slavery because of slavery. Jefferson Davis’s five-thousand-acre plantation, Brierfield Plantation, is just a few miles outside the city limits, in the same county where I was born and raised. I learned that Ulysses Grant’s strategy for the forty-seven-day siege and capture of Vicksburg, in which he forced Confederate lieutenant John C. Pemberton to surrender, is still considered one of the most impressive feats in military history. Fittingly, on July 4, 1863, Pemberton gave the city to Grant and the Union and freed all the enslaved.

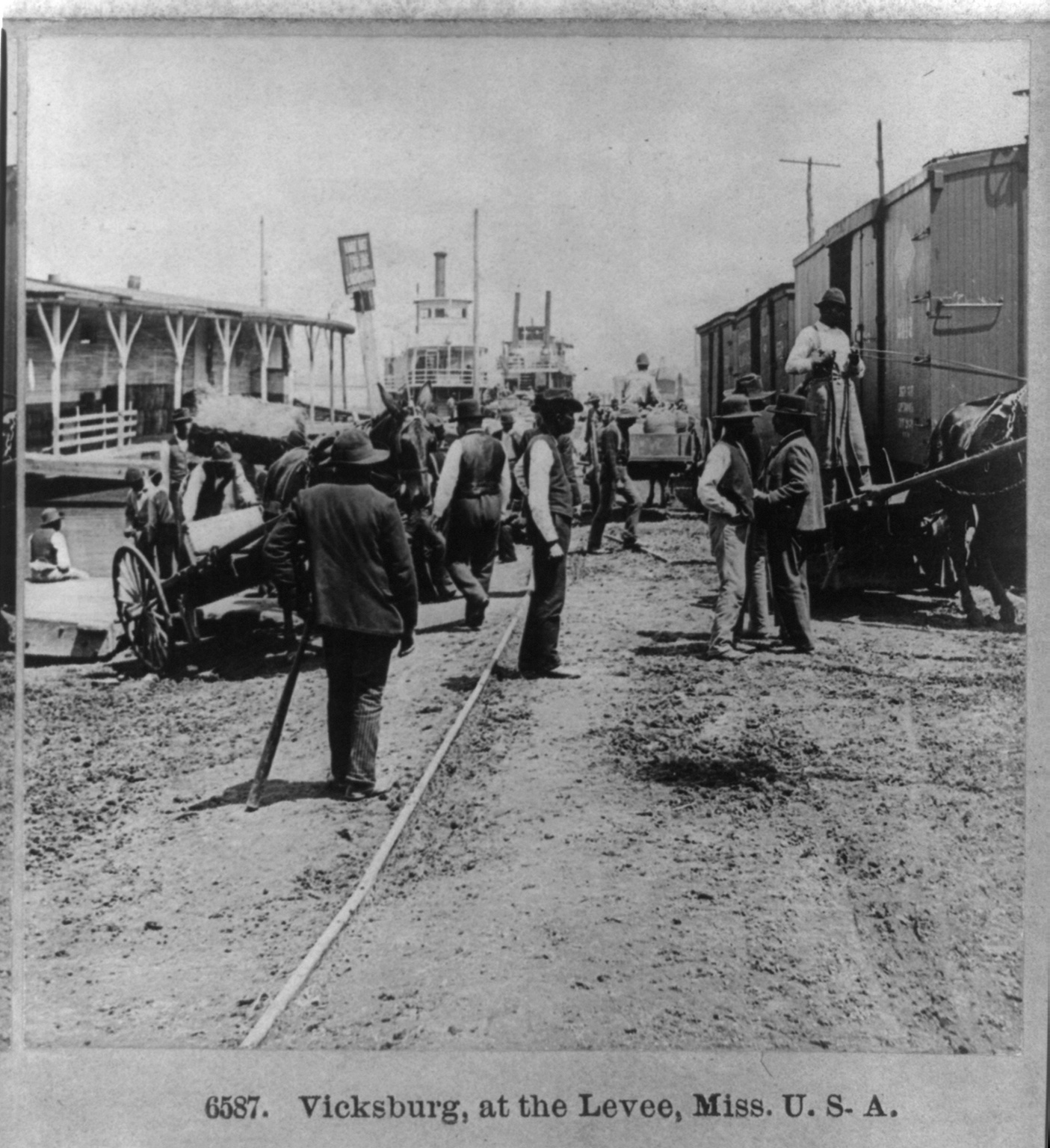

Vicksburg’s location on the Mississippi River’s east bank, between Memphis and New Orleans, strategically positioned it to be a major American river port city after slavery. In fact, Vicksburg was the most populous city in Mississippi in the late 1800s—and home to the state’s largest African American community. It was as crucial to the national economy as New Orleans, Memphis, or St. Louis, with a vibrant musical scene to boot.1

But in 1876, the powerful river changed its own course, and the city’s dreams of glory gradually dried up with the former riverbed. Though the US Army Corps of Engineers started constructing the Yazoo Diversion Canal two years later, it wasn’t complete until 1903. The city once again had river traffic access and a boost to the local economy, but any dreams of being a major American city were long gone. Vicksburg is now known as a small town at the southern tip of the Mississippi Delta. A little over twenty thousand people live there; 70 percent of them are Black, and about 30 percent live below the poverty level.2

Although Vicksburg doesn’t have any Fortune 500 companies or major league sports teams like New Orleans, Memphis, or St. Louis, its economy still does alright because of the city’s three US Army Corps of Engineers’ sites and tourist destinations including a historic national military park, a downtown filled with family-owned independent businesses, and four riverfront casinos.

The largest demographic of tourists are white retirees from other parts of the American South. They stay in a bed-and-breakfast antebellum home, spend half a day in the Vicksburg National Military Park, visit the Old Courthouse Museum and the Biedenharn Coca-Cola Museum—where Coke was first bottled—take an afternoon walk around the stores downtown, then go to dinner at Rusty’s or Walnut Hills at night.

I didn’t perceive it when I lived there, but now I see Vicksburg’s charm when I return for visits. When I was young, I rarely went down to the stores and restaurants on and around Washington Street, which make up the heart of historic downtown—and downtown had not yet been spruced up back in the late 1990s and early 2000s anyway. Back then, I mainly traveled between home, school, church, and relatives’ houses, all places that were 100 percent Black.

My efforts to learn the history of my hometown brought to light the violence that underlies its charm. During Reconstruction, as many as three hundred Black citizens were massacred on December 7, 1874, when freedmen organized to reinstate the city’s first Black sheriff, who had recently been kicked out of office.

In 1919, a Black man named Lloyd Clay was lynched on the corner of Clay and Grove Streets, just a minute from my grandparents’ house and a few minutes from historic downtown. Accused of raping a white woman named Kelly Broussard, Clay was tracked by bloodhounds, attacked by a mob, stripped of his clothes, dragged down the street naked, and left to burn and hang. Over a thousand white residents watched, shouting angrily. The lynchers even got their children involved, passing out rope they used to hang him on as souvenirs.3

Violence of a different kind caused harm to many Black families. Joseph Biedenharn, the creator of bottled Coca-Cola, made a considerable fortune by cofounding an aerial crop dusting company. Located across the Mississippi River in Monroe, Louisiana, Huff Daland Dusters, “the world’s first aerial pesticide application company,” helped eliminate the threat of the boll weevil—a beetle that feeds off cotton.

The company fattened the pockets of wealthy white plantation owners at the expense of the majority-Black sharecropping communities who lived in the area in which the pesticide was applied. Though the pesticides were advantageous for cotton production, they destroyed the gardens that Black people relied on for a healthy diet. In addition, constant exposure to the chemicals lowered their life quality and life expectancy.4

Some Black residents threw objects at the crop dusters in retaliation, but it did little good. By the end of the 1960s, Mississippi Delta civil rights leaders like Fannie Lou Hamer were convinced that tactics like spraying pesticides on gardens were used to starve Black communities who were intent on exercising their full rights as citizens. “Where a couple of years ago white people were shooting at Negroes trying to register, now they say, ‘go ahead and register—then you’ll starve,’’’ Hamer proclaimed.5

Many Black folks left Vicksburg and other majority-Black cities in the Mississippi Delta during the 1960s. They took northbound trains and got off at stops like Gary, Indiana; Chicago; and Milwaukee. But my grandparents on both sides stayed. And I finally found a book that described their experience.

Of all the books I’ve read about Vicksburg, only four are dear to my heart. The first is the Narrative of Henry Watson, A Fugitive Slave, written in 1848 by an enslaved man who spent time on a plantation in Vicksburg during his childhood. The second is Christopher Morris’s Becoming Southern: The Evolution of a Way of Life, Warren County and Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1770–1860. It is one of the few books on Vicksburg that does not focus on the American Civil War battle—instead, it tells an earlier story of how the city became so important. The third is I am the Blues: The Willie Dixon Story, the autobiography of our famous blues legend.

The fourth, and my favorite, is a memoir by Charles Chiplin called Roads from the Bottom: A Survival Journal for America’s Black Community. Chiplin’s father, the local leader of the Civil Rights Movement in Vicksburg, was a pastor like my grandfather, who was also heavily involved in the movement.

Before I read the memoir, I didn’t know my grandfather had risked his life for civil rights, organizing and protesting in the area known as Marcus Bottom. He and many other Black residents boycotted white businesses after a group of white men gang-raped a Black girl and no one was punished for it. I didn’t know the residents started a newspaper, Vicksburg Citizens’ Appeal, that discussed this incident and more for four years, from 1964 through 1967.

Before reading Chiplin’s memoir, I associated Marcus Bottom with good sandwich meat from Jimmy Choo’s, fresh catfish from Jerry’s Fish Market, and being the Blackest, poorest, and most stigmatized part of town.

On one of my visits home, just a few months before my grandfather died, I asked him about Marcus Bottom, the Civil Rights Movement, and what it was like to be a pastor in those days.

“Grandaddy, I read a book about you. It said you fought for civil rights back in the sixties.”

He brushed me off like a mosquito in the summertime.

“Aww, mayne. Don’t you worry nothing about that! I fought that fight so you wouldn’t have to. Don’t you get caught up in that mess now. I took care of it for you.”

It was clear he didn’t want to talk about it. I suspect it was too painful for him to relive those memories of near-death experiences. I asked the same question a few more times, hoping that phrasing it differently would open him up, but it didn’t work.

The truth is he didn’t take care of everything. He may have tried, but forces much larger than him have stalled the fight for freedom. His house, located in a quiet ghetto in Vicksburg’s North Ward, was proof of that. He knew I understood the complicated legacy of his civil rights work from the day I told him I had won a fancy scholarship, named after a dead wealthy white man named Cecil Rhodes, to study Black history at the University of Oxford in England. He knew nothing about the scholarship, but when I showed him the letter of congratulations from President Bill Clinton, he cried and told me he was proud of me.

It’s the only time I ever saw him cry. We made him a copy and hung it on the wall. He told me that he would’ve become president, too, if the white folks would have let him.

Vicksburg, after all, is ours, at least demographically. The city may not be the key to the South it once was, but exciting history is still being made there. The most famous people who grew up with me from the early 1990s to the mid-2010s were the NFL player Malcolm Butler, who graduated from Vicksburg High School a year before me, and the rap producer Wheezy (Wesley Tyler Glass), who graduated a year after me.

When I think of Vicksburg, I don’t think about its distant past. I think of how ironic it is that, until 2020, our mall was named after John C. Pemberton, the Confederate general who never wanted me, Malcolm, or Wheezy to be free. When I think of Vicksburg, I think of the skating rink I used to go to on Saturdays on Frontage Road to play with other children—Big Wheelie. It’s still open, and as far as I know, it’s thriving. I think of old-school lowriders, candy painted, with loudspeakers blasting David Banner and Lil’ Wayne. I think of all the long walks with my mom at the Vicksburg National Military Park—until my mom heard there were recent sightings of snakes and coyotes out there, and she got scared, and we stopped.

I think of the one time I went to the Miss Mississippi Pageant. It’s our city’s biggest annual event, but I was never too interested in it. But one year, my mom had an extra ticket, so I went—not because I was interested but because I wanted to spend quality time with my mom.

I think of that time when, as a senior in high school, I went to the Vicksburg Theatre Guild to see the play Gold in the Hills. It has been running there every year since 1936, making it the Guinness Book of World Records’ longest-running show.

When I think of Vicksburg, I think of the fact that I went to a high school that was 75 percent Black, yet the Advanced Placement classes I took were, at maximum, 20 percent Black. I think of one Black student murdered outside the athletic fieldhouse by a Black man who didn’t go there. I think of another Black student killed a few years later by a fellow student on a block near his home. I think of a Black student who, when I was in fifth grade, got upset when a teacher told him to be quiet, got out of his seat, walked straight up to her, knocked her out, and hospitalized her. I never saw him (or that teacher) again.

I think of all the Black students who started with me but didn’t graduate, whom I haven’t seen since I left home in 2010.

I think of all the Black students still going there now, and I hope and pray they get a quality education in a safe environment.

Detroit Publishing Co., courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Vicksburg, like all cities, is complicated. Though we have world-class engineers who try to control the flow of the Mississippi River at the three US Army Corps of Engineers sites, most of them would rather live over fifty miles away in Madison so their children can go to a “good” public school district. My own pastor, who moved here from Detroit to lead a church plant, never moved to Vicksburg, deciding instead to live in Rankin County, and afterward in the city of Clinton.

Though Vicksburg gets hundreds of thousands more tourists than Rankin and Clinton, people of means would rather live in middle-class towns with higher populations of white people. Of all the books I’ve read on Vicksburg, I’ve never read one that talks about that.

For the last ten years, I’ve written poems and short stories set in my hometown, like Ernest Gaines has done for Oscar, Louisiana, and Jesmyn Ward has done for DeLisle, Mississippi. In my poems, I try desperately to connect my grandfather—who escaped a plantation in another city in the Mississippi Delta and started life anew in Vicksburg—with my own generation. One of them goes like this:

I used to want to skip History

Maybe because History skipped me

In that God-forsaken Delta land

In Mississippi

My grandfather toiled the land

But didn’t get a dime for it

So he made an escape

Though he coulda did time for it

—or even died for it.

He found a way to sever from The Man,

And get the hell up off that land,

Crossed a river, hid in bushes, did whatever that he can

To get to that city called Freedom.

He ended up in Vicksburg.

So I can’t say he found it.

But I say he got closer.

I say it’s somewhere ’round here.

I think. I hope.

But then again, I know niggas in county jail for selling dope.

I wrote another autobiographical sketch—the most complete of them all—about my experiences as a high school student going to the public library downtown. Through the transparent glass walls on one end of the building, I could read and look out at the men and women—mostly Black, some homeless—walking up and down the street corner, talking to themselves and others, often with brown bags in their hands. During my breaks, when I walked outside, they spoke to me. One man taught me about the Nation of Gods of Earths, an offshoot of the Nation of Islam. I was a devoted Christian then—still a Christian now—but I found his ideas fascinating and empowering.

One of my essays, tentatively titled “Brown Bags and Black Gods in Vicksburg,” is an ode to the people, the places, and above all, the Mississippi River you can see out of the transparent glass wall. The current conclusion ends with my view looking outside:

Not too far away in the distance, white folks lived in nice antebellum homes at the top of the hill. And just down the hill past all the old buildings, I could see that dirty brown god flow ever so gently. The Nile River, the axis of two early African civilizations, could not be any more beautiful—the river where God might have taken that black mud and shaped the Original Black Man. . . . Beyond the black gods walking the streets passing out knowledge, and the brown-skinned men drinking liquor out of brown-bagged bottles, beyond the Mississippi River, a dirty brown god itself with her steady ebb and flow, beyond the Vicksburg Bridge that I used to superstitiously hold my breath over when my parents drove across it, was Louisiana. I could see their swampland and wondered what kind of creatures lurked in that faraway jungle.

Perhaps one day I will complete my dream, a diverse collection of short stories and poems set in my hometown. Some would be nostalgic ones set at my public high school. Other stories would take place at my grandparents’ house in North Vicksburg, where my mom and her twelve siblings and their partners and children would all congregate, and sit on the front porch and gazebo alongside their big, lazy, mopey, blue-eyed dog named Clinton and whatever stray cats came around looking for food that day, and eat the same vegetables from the garden we helped pick earlier that week: tomatoes, okra, sweet potatoes, greens, sweet hull peas, and corn.

Another setting would be at my favorite aunt’s house, located one street from my high school. I sometimes drove there after school and hung out until it was time to be at work. I would watch soap operas, tabloid talk shows, and Sanford and Son with Aunt Rose while eating greasy Red Rose sausages—made only in Mississippi—and Little Debbie Honey Buns. Sometimes we wouldn’t watch any television at all. We would sit out on her porch and listen to the high school marching band practice. She lived so close you could hear them loud and clear. My favorite year was the one in which they featured the music of Earth, Wind & Fire.

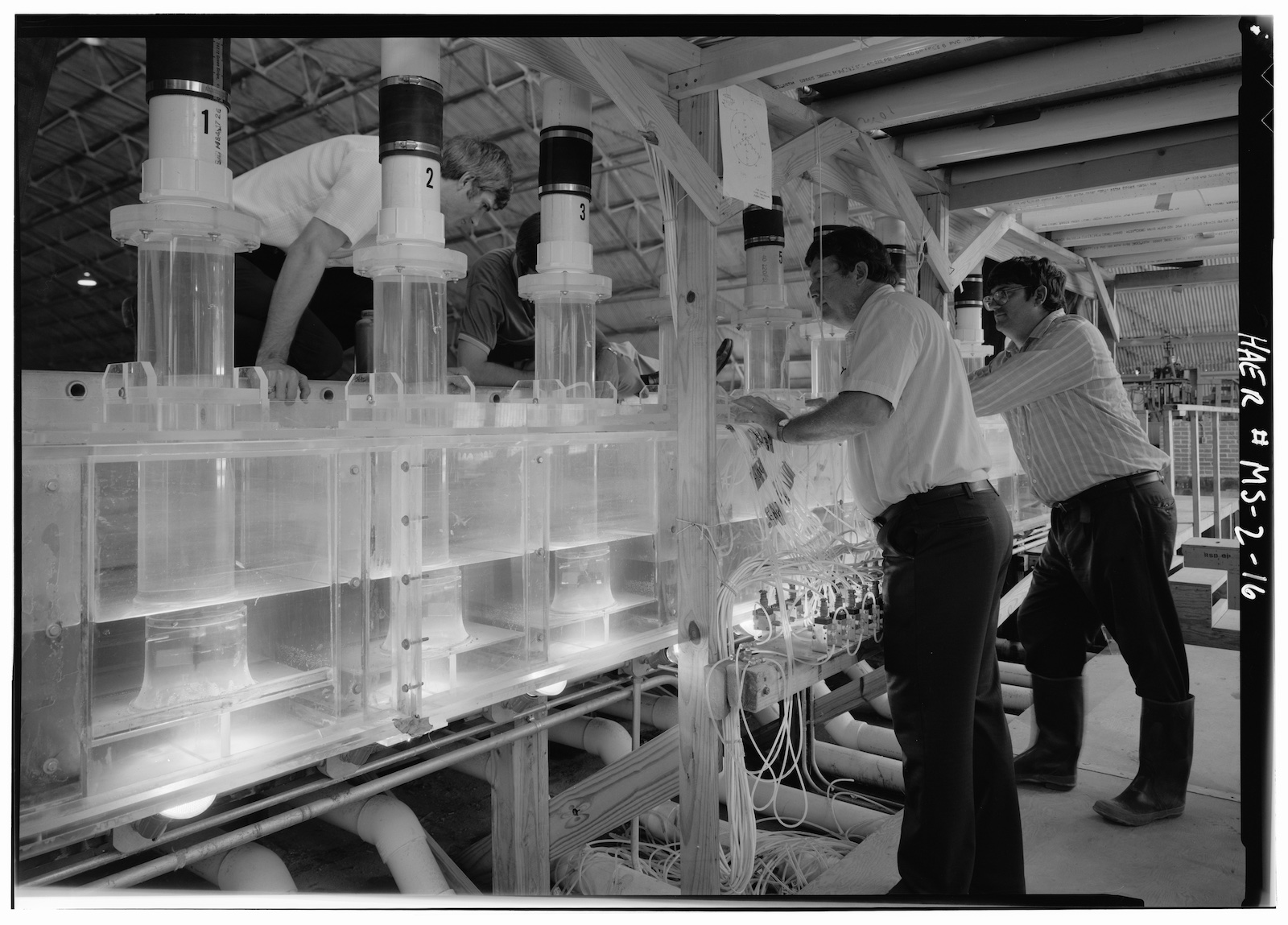

Another story—a Southern Gothic murder mystery—would unfold at the Vicksburg National Military Park. Others would be told from the perspective of engineers who worked at the US Army Corps of Engineers Waterways Experiment Station during a catastrophic flood.

I made considerable progress on that collection during the beginning of the COVID pandemic. I had moved back home with my parents for what ended up being a few months. During that time, we all held our breath, formed our social circle, and rode it out the best way we knew how.

To fill the spare time I had at the beginning of the pandemic, I drove to my old high school and took pictures to refresh my memory before I recreated it as a fictional setting. I especially wanted to look at those statues in the back lot off Confederate Avenue, where the teachers parked. I wanted one of my stories to discuss how ironic it was that this majority-Black school was literally on Confederate Avenue.

The students in my short story would start protesting because they felt they deserved a more robust history class. They wanted to discuss the local history that the higher-ups did not want to address—like the quotes and deeds of the white men of the Confederate army who have statues built in their honor that Black people in Vicksburg see every day as they drive or ride the bus to school. The students would demand the street name be changed, demand the curriculum be changed, and turn the city upside down.

To my surprise, I discovered that one of the statues erected on Vicksburg High School property is in honor of a man named—no lie—States Rights Gist. His father was a great admirer of John C. Calhoun, who of all US senators was the staunchest defender of states’ rights. Born and raised in South Carolina, Gist went to law school at Harvard and died as a militia general for the Confederate Army in the Battle of Franklin in Tennessee. Before dying in Franklin, he fought other battles, one of them in Vicksburg. His name would also be the short story’s name: “States Rights Gist.”6

I am convinced there are better and more recent stories to tell about my hometown than the same old ones white men keep telling about forty-seven days in 1863. Jefferson Davis, Ulysses S. Grant, and John C. Pemberton are not the most interesting historical figures to ever grace my hometown. And though I’m grateful for the scene with Loosh in The Unvanquished, William Faulkner’s stories are not the best I’ve ever read—or heard. The best stories I’ve ever heard came from my grandfather, aunts, uncles, and high school friends who freestyled while people like me—who couldn’t freestyle—mimicked the beat of Clipse’s “Grindin’” on lunch counters.

Looking back on my outline for a collection of short stories and poems, I realize I really just wanted to express to potential readers that many of Vicksburg’s citizens are beautiful people with rich traditions, yet are still starving to this day, not because of a siege, but because of state policies that overwhelmingly harm Vicksburg’s poor Black residents. Black folks throughout the state are starving for food—and for knowledge—at a rate that exceeds any other in this country because of systemic racism.

I wanted to remove that racism, but like Vicksburg’s ever-present kudzu plant, it is damn near impossible to contain once it takes root. Once you create the boundary language and social construction of Black and white, you’re stuck with the consequences for centuries.

Even though I don’t live there anymore, I wanted to show readers the “real” Vicksburg that I will forever call home and love despite its many problems.

I’m forever grateful for the Black folks before me who didn’t migrate north, enabling me to have such a great childhood in Vicksburg. Those Black folks deserve much more respect for their decision to stay in place than this nation will ever give them.

Vicksburg will always be my heart, soul, pride, and joy. It is land inhabited by a people with novel stories to tell for as long as humans are fortunate enough to remain there. One day, I hope my stories are good enough to faithfully represent the people with whom I grew up, like Ernest Gaines and Jesmyn Ward have done for their hometowns. Though my family and friends are often marginalized in published histories of Vicksburg, they are the descendants of the enslaved and sharecroppers—and the backbone of not just Vicksburg, but the entire state and nation.

Donald Kizza-Brown is a presidential diversity postdoctoral fellow at Brown University specializing in twentieth- and twenty-first-century African American and Southern literature. Kizza-Brown is working on a book based on his dissertation to be published by Johns Hopkins University Press and a biography of Richard Wright for Harper Collins/Hanover Square Press.

Header image: Levee and steamboats, Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1864, by William Redish Powell. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

NOTES

- “Marcus Bottom – Vicksburg,” Mississippi Blues Commission, Mississippi Blues Trail, accessed August 10, 2024, https://msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/marcus-bottom. Folklorist Bill Ferris was also born and raised in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and has done considerable work representing the area’s African American community. Raven Jackson’s 2023 film, All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, continues in this tradition.

- “Course Changes of the Mississippi River,” National Park Service, accessed January 13, 2024, nps.gov/vick/learn/nature/river-course-changes.

- Albert Dorsey, “A Mississippi Burning: Examining the Lynching of Lloyd Clay and the Encumbering of Black Progress in Mississippi during the Progressive Era” (master’s thesis, Florida State University, 2009).

- Brian Williams, “‘That We May Live’: Pesticides, Plantations, and Environmental Racism in the United States South,” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 1, no. 1–2 (2018): 15.

- Williams, “‘That We May Live,’” 15.

- Walter Brian Cisco, States Rights Gist: A South Carolina General of the Civil War (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane, 1991).