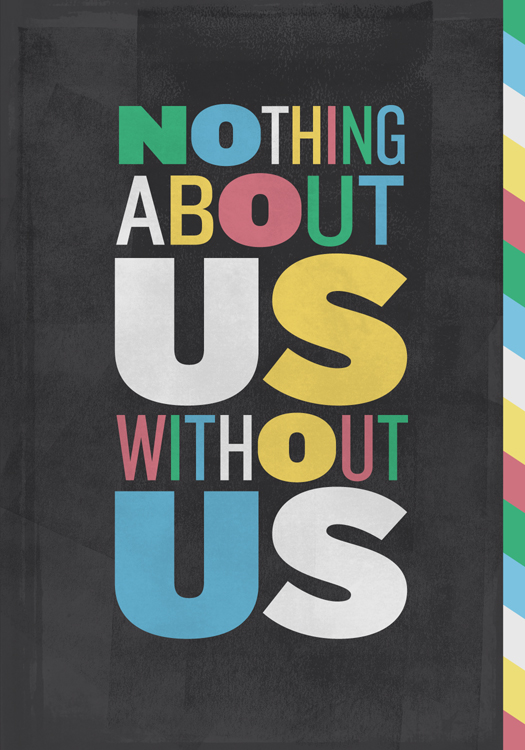

“Nothing about us without us.” This call—first made by disability-rights activists in South Africa and since taken up by disabled people around the world—not only signals the central demand of disabled political movements for access, equity, and justice, it is also a connected reminder to those who tell the stories. Rejecting the well-worn narratives of pity, scorn, othering, and medicalization that exist primarily for the benefit of the nondisabled, disabled people insist on better and richer stories about disability as a way of being and a way of knowing.

This issue is rooted in a commitment to this call. Our writers tell stories of the disabled South to place disabled people in the center of their own narratives rather than erase or marginalize them. Additionally, they insist that we understand the ways that disability has shaped southern experiences more broadly, and how centering disability and disabled people reshapes how we think about the South in past, present, and future. In doing this, they reflect not only the assertions of disabled political movements but the linked mission of Disability Studies.

The interdisciplinary scholarly field of Disability Studies is still relatively new, having emerged alongside the Disability Rights Movement. Like its close counterpart, Disability Studies aims to transform the understanding of disabled people by debunking harmful stereotypes and celebrating disabled lives, communities, and ways of knowing. Disability historians have uncovered disabled stories and reframed larger histories (immigration, colonialism, slavery, war) around a disability-specific analysis. Social scientists have explored the larger growth of systemic ableism and its specific manifestations in employment, health, housing, education, and beyond. Critics have unpacked representations of disability in literature and popular culture and analyzed intellectual and artistic traditions among disabled people. And, crucially, memoirists have forged new languages in the pursuit of self-definition.

In recent years, the study of disability has opened and expanded in important new directions. Communities that were previously marginalized both within the scholarship and the politics—including disabled people of color, LGBTQI+ disabled people, and those with intellectual, psychological, and sensory conditions—have insisted on analyses that better reflect themselves and thus improve all understandings. Transnational scholars show the potential of thinking beyond national borders. Futurists articulate fictional and nonfictional visions of worlds to come that center disabled people rather than erasing us. And artists show the potential of old and new media in creating different and more accessible conversations. Regardless of form or format, emerging Disability Studies scholars build on earlier breakthroughs while insisting on new and better ways of understanding, imagining, and creating.

In this way and others, they remain in conversation with disability artists and activists. The mid-2000s development of the “disability justice” platform, by the collective of Black, Brown, and queer disabled people known as Sins Invalid, pushed beyond disability rights in calling for an intersectional and radical politics. Activists, artists, and everyday people have taken up this call. Direct-action campaigns have preserved and expanded legal protections. Arts-based and literary communities have made space for disabled people to tell their own stories and create together. And social media has become a particularly vibrant place for organizing, resource-sharing, community-building, laughing, loving, mourning, and world-building. In the COVID era, these virtual spaces have taken on a new level of importance in facilitating survival, resistance, and joy. And new disability organizations—like the New Disabled South, which focuses specifically on southern states—have combined these new strategies with older methods to build for the future.

None of this is possible without disabled people’s stories being told and embraced. And that requires a dual focus: we have to face the violence of ableism, especially as it continues to reverberate throughout the lives of disabled people, and we also have to celebrate the ways that disabled people resist, reclaim, and recreate in spite of it. Disabled people do this all the time—it’s how we make it in an inaccessible world—and the most important activist, scholarly, and artistic discussions of disability express this duality.

Our authors all engage this spirit. They describe the brutal realities of ableist beliefs and practices in the South and the ways that they have intersected with other systems of injustice. Shelby Pumphrey confronts forced sterilization in Virginia as a shared tool of ableist institutionalization and anti-Black violence. Keri Watson presents Eudora Welty as a photographer in the context of a disabled man who challenges and complicates Welty’s gaze. Simon Buck considers the amputee musicians who played the unfair changes of a post–Civil War entertainment world framed by the freak show and the minstrel show. Across this issue, our authors force us to confront the way that ableism has defined the experiences of disabled southerners and distorted all of its residents regardless of identity.

But these are not just more stories of tragic disabled victims. Our authors also consider the determined and imaginative ways that disabled people persist, innovate, and remake our worlds. Here is Adria L. Imada’s chronicle of resilient community-building among leprosy patients in Louisiana and Hawai’i. Here is the generational legacy that R. Larkin Taylor-Parker finds in a possibly autistic family member. Here are the joyous, bluesy remixes of history created by the Krip-Hop Nation and its cofounder Leroy F. Moore Jr. Here is the artwork of Patrick Dean, using adaptive methods and new themes to transform his work in the aftermath of an ALS diagnosis. And here is Camisha L. Jones, in conversation with Beyoncé, with an invocation that both remembers and rejoices. Their work honors the disabled ancestors who made a way, and it heralds the disabled people in the future who will make that way better.

This issue offers only a tiny fraction of the universe of stories contained within the disabled South. If you’ve not previously thought about disability in these ways, I hope this is a good introduction. If you’ve thought about it a lot, I hope these astonishing glimpses into just a few disabled experiences in the South will enrich you. This is a small part of a growing conversation that needs to be expanded and continued. Let these responses be a call to others (perhaps you) to continue that conversation.

Most importantly, if you’re disabled, I hope you find yourself in this issue. It may be because of a direct connection to yourself. It may be because of an indirect resonance that you feel from these stories. Or it may be because you want more about your life and the world you occupy, so you will help us all tell better stories in the future. Regardless, I hope you find your community here. Because we need you.

Nothing about us without us.

This essay introduces the Disability issue (vol. 29, no. 1: Spring 2023), guest edited by the author.

Charles L. Hughes is a writer and historian based in Memphis, Tennessee. His books include Country Soul: Making Music and Making Race in the American South and Why Bushwick Bill Matters, and he has written articles on a variety of topics in a range of publications. He is associate professor of urban studies and director of the Lynne & Henry Turley Memphis Center at Rhodes College.

Header image: theendup / Alamy Stock Photo